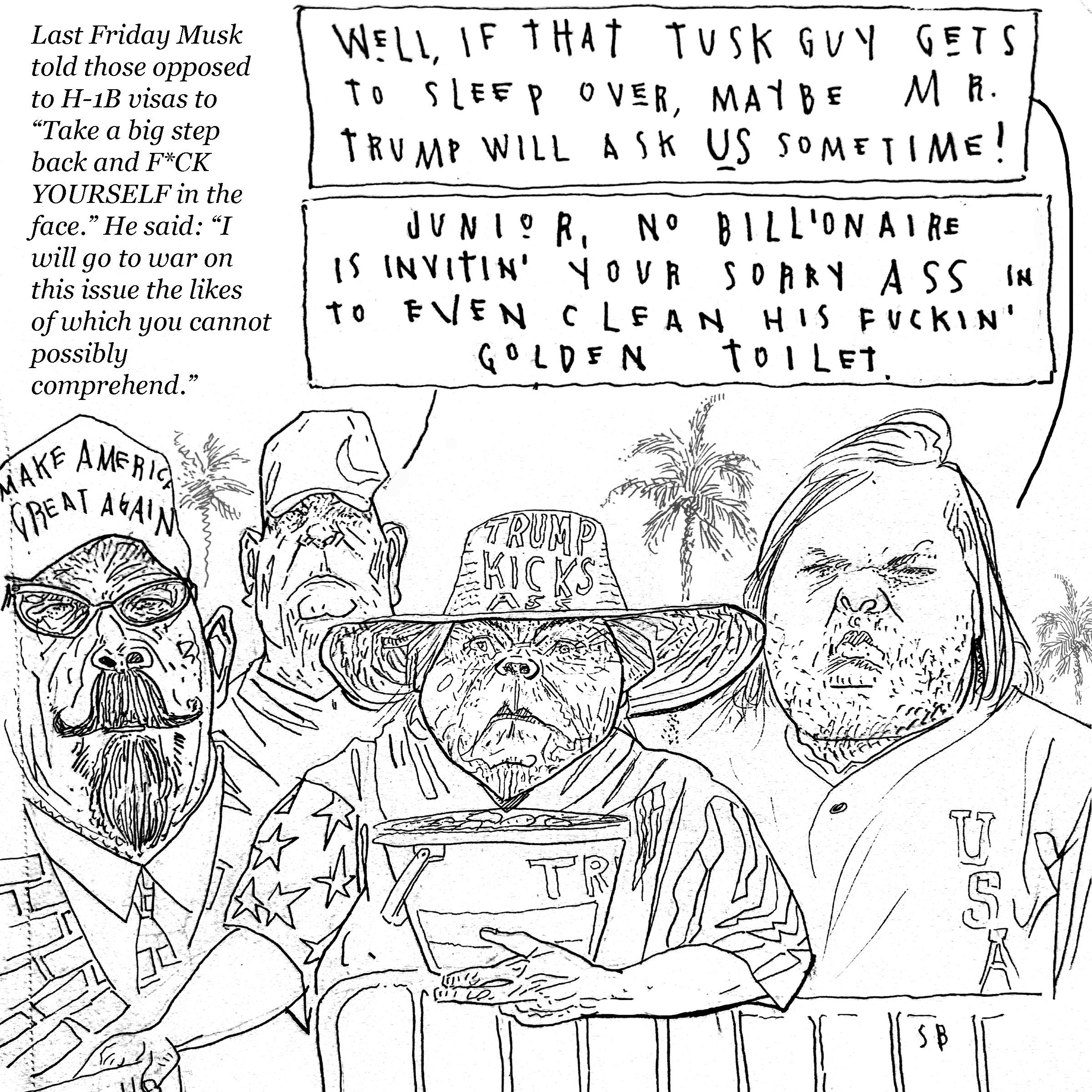

Junior at the dawn of revelation.

A few thoughts suggested by the new film A Complete Unknown, in which we see, as told in the life of Bob Dylan, the powerful war between, not just styles of art, but basic understandings of what art is for.

Greenwich Village in 1961 is a hotbed of fulminating reaction to McCarthyism and American monoculture. Folk music was one of the many ways in which intellectuals, outsiders, progressives, contrarians, revolutionaries, etc. finally found expression. At long last many things that had been ignored were at last being discussed. Dylan walks into this with a passel of songs and a brilliant mind working overtime to synthesize the issues of the moment into one anthem after another that would be adopted by a hungry generation. In the process, he becomes a superstar. And as his reality changes, he sees less and less the need to discuss literal issues. The film ends in a kind of musical battlefield, taking place at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, where Pete Seeger and other friends try to persuade Dylan not to plug-in during the festival. It seems to me that plugging in is not nearly as important as the messages that are now going to be delivered by Dylan. The song he sings with a band of electric musicians, has nothing to do with any political or cultural issue. (His big needs, in the film, seem to be about trying to get down on paper the surging creativity of the muse as well as juggling girlfriends; not voting rights, war or any abstractions of that kind.) Seeger tells him he ought not to abandon the cause of folk music because protest itself has overarching importance. But Dylan, at this point, couldn’t care less.

Manohla Dargis in the New York Times, continually refers to Timothée Chalamet as Dylan, in the film, as “cool.” And denigrates Pete as “saintly“ and “suffocatingly sincere.” She doesn’t care to recognize that what we are seeing is the distinction between two different art forms. It is the difference between narrative art that lives for being beautiful and powerful and on a mission, and pop and rock which doesn’t have to concern itself with that last part. Political art is on a different journey: to tell the truth about literal topics in the very best possible way.

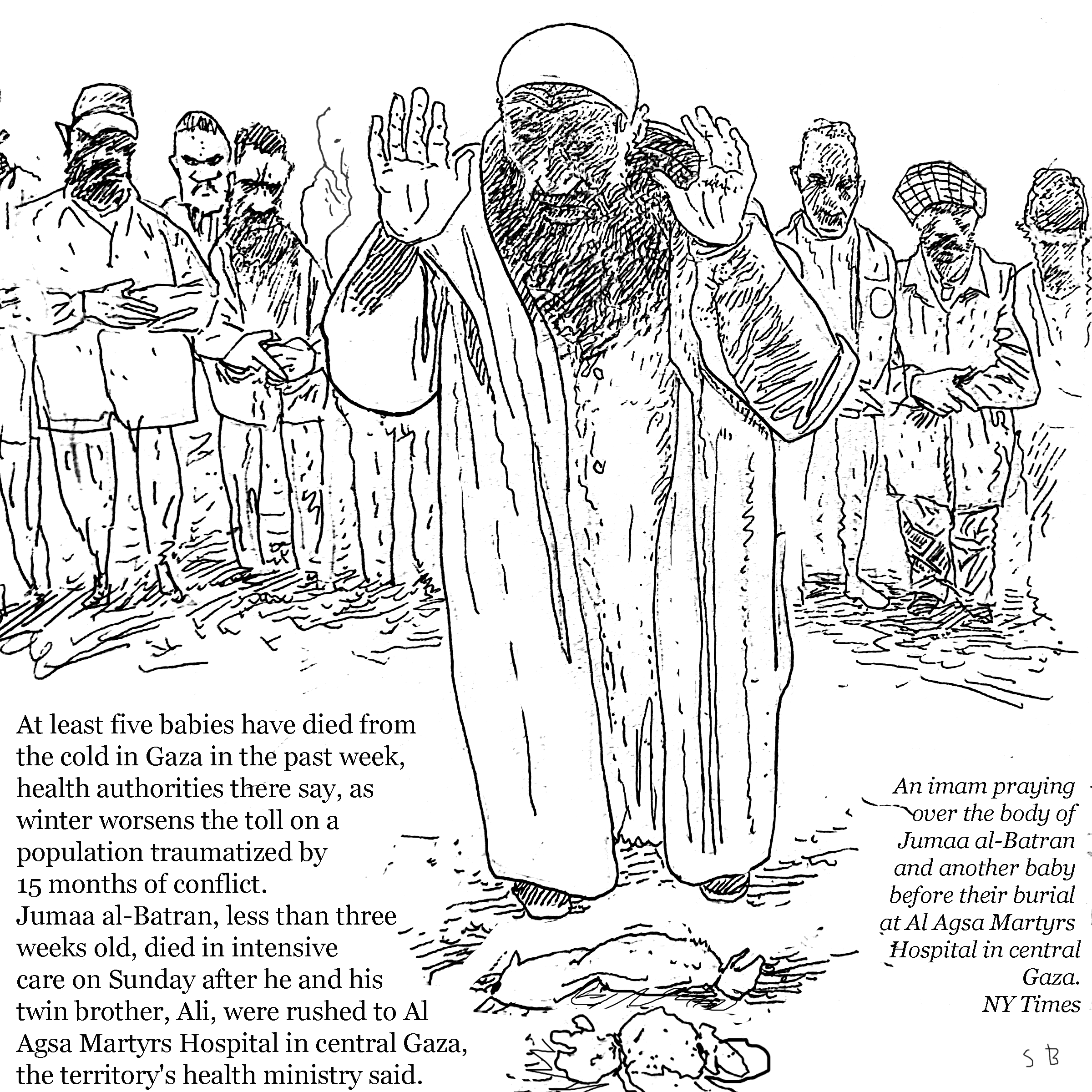

In the December 19, 2024 New York Review of Books, there is a piece by Wesley Lowery, in reaction to the presidential election. He urges a dedication to narrative, referring to a book by Rev. Levi Jenkins Coppins written in 1891: “Our highest calling, he stressed, is not short term persuasion of immediate influence, but diligent documentation.”

It may seem that art that narrates and documents is the poor step-child to “real“ art. To me the most real art is the art that asks “What is it like to be human?“ A portrait, a collection of people in a situation, in relationship to one another, in relationship to systems and elements that define existence: these are urgent stories we tell. Art that is about these things even in metaphor is what Seeger stood for. And though as the years pass, his name will not be as well remembered as will be Dylan’s, they all, and we all, are part of that movement. And I suspect that, finally, Bob Dylan’s best remembered work was done with a very unplugged pencil.

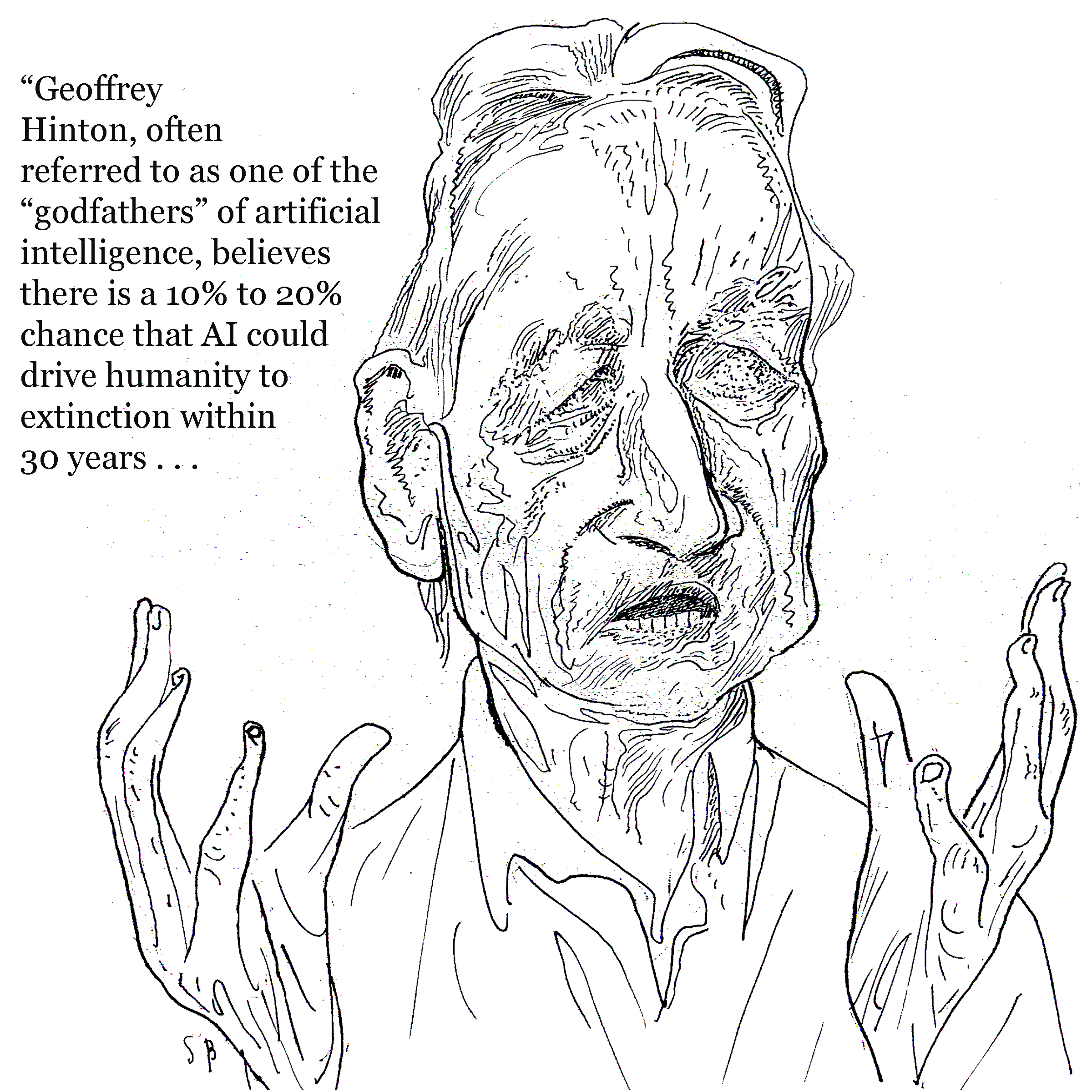

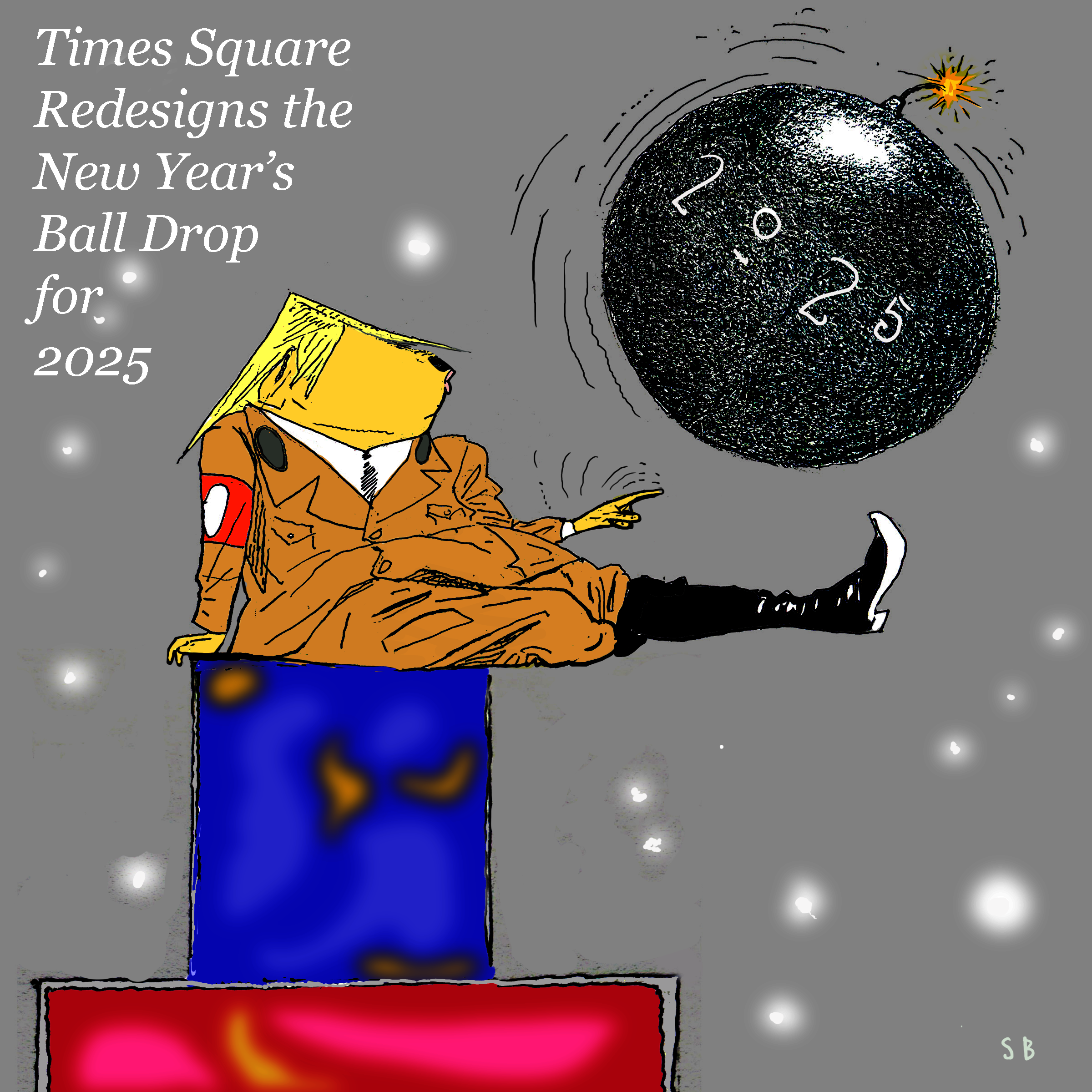

The most important question today, I think is: what will we do during the persecutions, debaucheries and corruptions to come?

I don’t have the complete answer, but I know part of it: get it all down.

It will be a war not only against MAGA, but against forgetting.

I’ll bet Junior gets the whole concept by breakfast.

Meantime inside at Musk-a-Lardo, the guests are asleep on couches and the empties are being carried out by, probably, undocumented labor, secure in the notion that Trump will refrain from deporting people who, after the election, matter much more to him than Junior.