The Unsettling Genius of David Lynch

In his films, his TV shows, and his paintings, Lynch reminded us that all art gestures toward a world beyond the familiar and comforting.

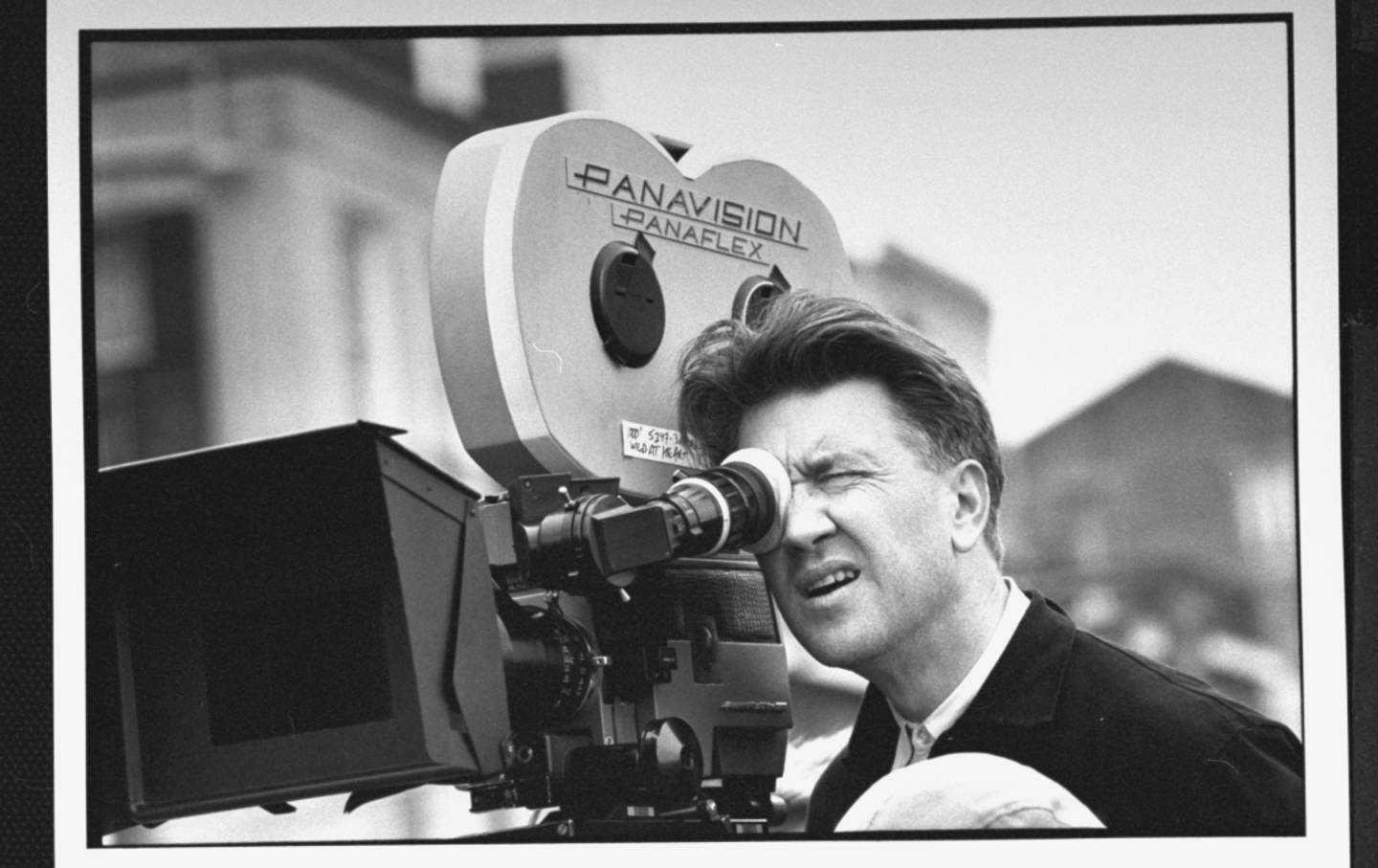

David Lynch at the filming of Wild at Heart.

(Acey Harper / Getty)

In trying to write on David Lynch one begins to understand why words did not come easily to him. In a beloved clip of the surrealist filmmaker, who died this week at 78, an interviewer asked him to “elaborate” on his statement that Eraserhead is his “most spiritual film,” to which Lynch responded affably enough: “No, I won’t.”

In retrospect, what could he have said? Critics and scholars have striven nobly for decades to translate Lynch’s films into language, to find a way to convey the propositions about the mind and the soul and the world they contain. But however much our experience of the films may be deepened by accounts of how they illustrate this or that concept from Lacanian psychoanalysis or Vedantic mysticism, his films often escape the boundaries of the spoken; they tend to transcend the forms of communication they themselves utilize. The experience of them is itself primary. There is always something irreducible and incommunicable about his art. The indelible moments—the Roy Orbison karaoke in Blue Velvet, the woman in the radiator singing about heaven in Eraserhead, the prophetic utterances in the Red Room in Twin Peaks, the starry night at the end of The Straight Story, the mysteries of Club Silencio in Mulholland Drive—endure because their meaning can never be exhausted by analysis.

The film scholar Martha Nochimson once told a story about how she confessed to Lynch that she didn’t understand a painting by Jackson Pollock that Lynch had admired. Lynch replied that when they encountered the painting together, he could see her eyes move over the painting, taking it in, and that for him that simply was what it meant to understand it. The movement of eyes, the absorption in image and speech, the rapture of emotion and imagination—these were for him the signs that a viewer was truly receiving what he was trying to express in his art.

Lynch was a painter as well as a director, and many of his own paintings explore the power that language derives from its limits. Strongly influenced by the work of Francis Bacon, these paintings pair surreal imagery with text that at once succeeds and fails to describe what we are looking at. A monstrous figure wields a gun and a knife and strides across a barren landscape toward a box resembling a television within which a female figure is confined: “pete goes to his girlfriend’s House.” A man with a grotesque mask-like visage stands in an empty space, a bloody wound consuming his chest and out of which a protuberance like a giant earthworm extends: “this man was shot 0.9502 seconds Ago.”

In his film as well as in painting, Lynch wanted to remind us that the value of language as a means of communication often lies in its ability to flaunt its own inadequacy. All art, he insisted, offers us more than what it could itself convey. It always gestures beyond itself, toward everything it can’t say, opening back up everything that is closed off by the comforting illusion of conceptual mastery.

My favorite moment in all of his work comes in an episode of the second season of Twin Peaks in which a brutal act of violence the protagonist has been trying to prevent comes to pass, though he does not know it yet. A mysterious and possibly supernatural figure, an old man apparently wracked by senility, approaches him, puts a hand on his shoulder, and says: “I’m so sorry.”

There are no words that can fix anything, no formulation that will make it all OK. And yet in that gentle acknowledgment of futility there is the possibility of transformation—transcendence. “Silence,” Lynch once remarked, “is this basis on which all these sounds and other things come together.”

Lynch began his career training in visual art at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in Philadelphia. There he also began to make short films that leaned heavily on animation. A grant from the American Film Institute allowed him to make Eraserhead, his debut feature, over five years. A dreamlike film stuffed with bizarre and sometimes stomach-churning imagery, it nonetheless won Lynch enough attention to let him take a stab at mainstream Hollywood filmmaking. One of his first attempts was a colossal failure: the 1984 Dune. But by the early 1990s, Lynch had established himself as a popular and bankable director. Blue Velvet became an art-house favorite, Wild at Heart won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and the Twin Peaks television series was picked up by ABC.

And then Lynch stopped giving people what they wanted. He retreated from Twin Peaks after the network forced him and his show-running partner Mark Frost to reveal the solution to the show’s central mystery. Ratings plummeted; the show was canceled.

Lynch returned with a feature film, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, that bombed at the box office, allegedly got booed at Cannes, and was for years widely considered one of Lynch’s worst films. After a five-year hiatus, he returned with a string of films—Lost Highway, Mulholland Drive, and Inland Empire—that radically discarded Hollywood conventions of character and narrative; it was punctuated by a G-rated film, The Straight Story, about a guy driving a lawn mower across Iowa.

By the aughts, critics had warmed to Lynch again. Then he abruptly retired from feature filmmaking. The only major cinematic project Lynch completed after Inland Empire in 2006 was the revival of Twin Peaks on Showtime in 2017, whose intensely avant-garde style delighted cineasts but mystified fans and scared studios away from Lynch for the rest of his life.

Even in the midst of all these ups and downs, Lynch’s artistic output was primarily characterized by silence: long silences between releases, uncomfortable silence from critics and audiences in the face of work they were not expecting, and occasionally a challenging wordlessness on screen, as in an especially polarizing sequence in Twin Peaks: The Return that featured a janitor sweeping a nightclub floor for several minutes. As Lynch understood, silence is too often scarce in our age. “It’s a really noisy world,” he once noted, and he therefore tried to create in his art a space where the generative forms of absence crowded out by our compulsion to busy production could dwell.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →But even as Lynch aspired to help his viewers to rediscover the value of silence, his films were rarely silent in a literal sense. When there wasn’t music or speech there was some other kind of noise, rumbling, humming, whooshing, rattling, clanging. These sounds are often described as “unsettling,” which is at once appropriate and strange since they are also the ambient noise of modern life—electricity and motors.

Lynch’s work is unsettling precisely because it gives us the world we inhabit in ways that help us recognize it as the nightmare it so often is. The world he presents us is uncanny in the sense Freud exposited: unheimlich, un-homely. Lynch’s affection for The Wizard of Oz is well known and his art too tells us that there’s no place like home. But it is art for people who don’t realize they are in Oz, people who wrongly believe they are home when they have never really been there.

“A little girl went out to play. Lost in the marketplace as if half-born”—this cryptic parable, delivered by a seeress at the beginning of Inland Empire, is perhaps Lynch’s most succinct statement of his cosmology. There is a “way to the palace,” the old woman explains, a pathway not “through the marketplace” but “in the alley behind” it. But, she says, “it isn’t something you remember.” The purpose of Lynch’s art is to help us remember.

One of the homes we mistake for our own, Lynch perceived, is the household, the home of the “traditional” American family. In nearly all of his films the nuclear family turns out to be a fathomless reservoir of violence and cruelty: the grotesque nightmare of coupling and reproduction in Eraserhead; the sadism encountered and sublimated by Jeffrey in Blue Velvet as he comes to replace his father; the abusive behavior the men in Lost Highway and The Straight Story have trouble admitting to themselves; the demonic parents and grandparents stalking the protagonists of Wild at Heart and Mulholland Drive. And then there is Twin Peaks, in which a detective unravels a tangled conspiracy of drug trafficking and Quebecois menace that keeps him from seeing until too late the horrible truth: that Laura Palmer was molested and murdered by her own father, a respected, upstanding attorney. In a famous episode of The Return, Lynch ties the evil at the heart of Laura’s nuclear family to the evil of nuclear weapons, the bedrock of the prison of homeland security.

Some fans were enraged by Lynch’s refusal to use the 2017 revival of Twin Peaks to serve them a reheated version of the original show. But while there is comfort to be found in Lynch’s work, he rarely will provide us with the comfort of the familiar. The comfort that one can find in his films is one of an estrangement that proves the possibility of liberation; the reassurance that this—this society, this family, this selfhood, this life—isn’t all there is. The reason you feel like you don’t belong is that you don’t. That awareness is disturbing but freeing, an invitation and a challenge to step outside yourself.

After the release of the feature film Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, which depicts the last days of Laura Palmer before her murder, “Lynch received many letters from young girls who had been abused by their fathers,” according to the filmmaker and Lynch scholar Chris Rodley. “They were puzzled as to how he could have known exactly what it was like.” I think the answer is contained in the image that begins each episode of the show: a waterfall pouring down in separate streams and then flowing as one into the pool below. None of us, and especially not David Lynch, are merely ourselves. Being ourselves, indeed, can be acutely painful, a site of bodily and social confinement. But that pain can be a gateway to an empathy more powerful and shattering than we believe to be possible, dreaming our dream of individuality.

There is something haunting about the fact that David Lynch was killed by fire: all the little fires in all those cigarettes all those years, and then at last the enormous Los Angeles wildfires that forced an evacuation his emphysemic body was apparently unable to handle. Fire was a nearly constant presence in Lynch’s work. In one of his final films, the 2020 animated short FIRE (POZAR), a match lit by a giant burns a hole in the fabric of the world, through which a worm-like creatures enters, triggering a sequence of apocalyptic devastation. This image is familiar in Lynch’s filmography; it has echoes in Inland Empire, Lynch’s earlier short Rabbits, and Twin Peaks: The Return, and all Twin Peaks viewers know that fire is a vehicle of transit “between two worlds.” But if fire, in eating through the firmament, can let into our world everything we wish to keep out, it also can create a portal for escape, a crack in the edifice that keeps us confined in this realm of loss and confusion. It can offer us an emptiness that is a silence that is possibility. In his death, Lynch has once more created a hole. It is up to us to go through it.

More from The Nation

“The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy “The Paper” and the Return of the Cubicle Comedy

The new show from the creators of The Office reminds us that their comedic style does now work in every “workplace in the world.”

The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…” The Strange Story of the Famed Anti-Fascist Lament “First They Came…”

In his celebrated mea culpa, the German pastor Martin Niemöller blamed his failure to speak out against the Nazis on indifference. Was that the whole reason?

The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme” The Grand Delusions of “Marty Supreme”

Josh Safdie’s first solo effort, an antic sports movie, revels in a darker side of the American dream.

John Updike, Letter Writer John Updike, Letter Writer

A brilliant prose stylist, confident, amiable, and wonderfully lucid when talking about other people’s problems, Updike rarely confessed or confronted his own.

TikTok’s Incomplete Story TikTok’s Incomplete Story

The company has transformed the very nature of social media, and in the process it has mutated as well—from tech unicorn to geopolitical chesspiece.