David Lynch’s Guts

His visceral films, which reflect the best and worst of American life, affected viewers in realms both conscious and unconscious.

David Lynch, 2002.

(Chris Weeks / WireImage)

In David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, college student Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) discovers that he’s both a detective and a pervert. The lengthy, disturbing sequence—involving Jeffrey as a Peeping Tom who witnesses a rape—contributed to the controversy surrounding the film upon its release; mass walkouts and refund demands, and deeply polarized reviews that levied accusations of sadism and misogyny, were all part and parcel of the initial reception. It also helped cement Blue Velvet’s legacy as a major work in Lynch’s career and American cinema. I’ve been haunted and captivated by it ever since my first viewing.

Explaining why that’s the case proves both somewhat straightforward and exceedingly difficult. I can point to various formal elements, such as cinematographer Frederick Elmes’s tense compositions, accented by low-key noir lighting that emphasizes the apartment’s red walls and the blue robe worn by Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini), or Angelo Badalamenti’s swirling crescendos in his score, which make it seem like the viewer is perpetually falling. There’s a static shot of an empty living room, with Dorothy getting undressed in a bathroom located down a hallway in the far left background, that resembles a painting but viscerally feels like drinking spoiled milk. The trio of exceptional performances by MacLachlan, Rossellini, and Dennis Hopper, as Vallens’s sadistic tormentor Frank Booth, create an axis of sex and violence so inextricably linked, so firmly American, that they leave a syndromic impression on the mind.

The sequence epitomizes the film’s thematic thrust, which, to my eyes, has always been that our best and worst impulses operate in tandem. Blue Velvet opens with a suburban man having a heart attack while watering his lawn on a gorgeous day; Lynch’s camera eventually pans away from the unconscious man and travels beneath the placid grass to find a plethora of swarming bugs. It’s one of his most evocative images, but as much as the easy symbolism of “the darkness beneath the surface” makes for a reductive, tidy summary of Blue Velvet, Lynch spends the rest of the film illustrating that light and dark, love and hate are on full display above ground. Jeffrey comes of age by probing the dormant evil inside him, learning the disquieting adult truth that bad guys are not “other people.” The moment when he sees himself in Frank, and Frank sees himself in Jeffrey, is when he realizes that he needs to determine what kind of man he wants to become.

More than the vast majority of directors from his generation, especially those who became a part of American popular culture, Lynch, who died last week at the age of 78, fulfilled the promise of film by transcending the limitations of language. The splanchnic feeling that his work generates can be explained or dissected—as many have done before, some with reasonable success—but doing so thoroughly risks reducing it to banality. Lynch understood that images were a code to the unconscious mind, a place where words can only accomplish so much. Sadly, words are all I have at my disposal.

There was a time before and after I knew about David Lynch, but the manner in which he entered my life remains hazy.

I believe the first film of his I watched was Mulholland Drive, back in high school, on an enthusiastic recommendation from my mother. It’s one of the only times I’ve ever watched a movie twice in a row, not only to satisfy my thirst for coherence but also to return to a fictional atmosphere that rendered my own strange and unfamiliar. I watched Blue Velvet sometime before entering college, but I don’t remember the viewing as much as I do the film blowing a shotgun-blast-sized hole through my psyche. When I finally watched Eraserhead, I barely breathed during the extended, hilarious chicken-dinner sequence; I remember thinking that the chilling camera movement from actor Jack Nance to a pair of whining dogs and then finally through a window perfectly captured how the worst nightmares feel ineffably mundane.

I watched most of the original Twin Peaks in high school after being gifted the gold-box DVD set for Christmas. I was stunned that the series’ most acclaimed elements—the feature-length pilot, the first dream sequence with the backward-talking dwarf, MacLachlan’s performance as Agent Cooper—were as capital-P perfect as everyone had said. My first message-board screenname was “TheOwlsAreNotWhatTheySeem,” a reference to the enigmatic proclamation delivered by Carel Struycken’s character the Giant. Many scenes from the original series still elicit tears, especially the monologue by Miguel Ferrer as FBI agent Albert Rosenfeld preaching nonviolence. (It’s Ferrer’s delivery of “My concerns are global” that always does me in.)

In the spring of 2017, Chicago’s Music Box Theatre programmed an exhaustive retrospective of Lynch’s work, including his commercials and music videos and other ephemera, ahead of the highly anticipated third season of Twin Peaks (also known as The Return), which would begin airing in May. Over a period of eight heavy viewing days, I watched the remainder of his work. I remember thinking that The Straight Story was the skeleton key to Lynch’s oeuvre. I remember watching Inland Empire stoned on a Sunday evening and genuinely feeling that I might die from sheer unease. I remember Lost Highway confounding me, possibly due to my ignorance of fugue states, O.J. Simpson, and sexual paranoia; it was only upon subsequent viewings that I began to glean its greatness.

I watched The Return every Sunday evening during its first broadcast, except for the widely acclaimed eighth episode—the one with the atomic bomb—because it aired on my birthday and I was having dinner with my parents at the time. It’s still difficult to convey how miraculous its existence felt in the moment, how something so singular and patient, so deliberately elliptical and elegiac, could air before episodes of the hour-long Showtime dramedy I’m Dying Up Here. (This is surely how it must have felt to watch the original Twin Peaks as well.) At the very end of its run—when a distraught MacLachlan asks, “What year is this?” and Sheryl Lee screams in terror—I remember feeling filled with immense gratitude for being alive to witness a masterpiece in real time, while still being paralyzed by anxiety and awe.

Lynch was a 20th-century man—1950s and ’60s iconography held permanent sway over his oeuvre—and yet his work always felt like it was in the perpetual present tense. The introspective, thematically recursive nature of his films makes them an evergreen canvas on which to project contemporary fears. Maybe his unwavering belief that our better angels can’t be so easily snuffed out feels hopeful instead of naïve because of how much he embraced the darkness of the modern world. Or maybe it will always feel like I’m communing with his spirit whenever the sound of my laptop overheating engulfs the silence of my bedroom.

These viewing experiences, though specific to my life, are no doubt shared by many. Lynch has a way of turning any remembrance into a personal affair, if for no other reason than that he invited people into his subconscious while leaving room for them to impose their own makeup. Since his films never hewed to the strictures of autobiography, let alone realism, they became a busy two-way street that made the relationship between viewer and filmmaker a uniquely intimate one.

If that sounds hyperbolic or sentimental, that’s because writing about Lynch in any kind of totalizing way inevitably means confronting hyperbole and sentiment. Many of the obvious clichés about him are plainly true: He was one of a scant number of popular American artists to bring an avant-garde sensibility into the mainstream. He was such a nonpareil filmmaker, his style so entirely his own, that his name became an (overused, yet still ostensive) adjective. The details of his rise to prominence—Mel Brooks tapping him to direct The Elephant Man after seeing Eraserhead; Twin Peaks turning out to be such a runaway success that it landed him on the cover of Time; Mulholland Drive rising from the ashes of a rejected ABC pilot—really can’t be replicated, even if the entertainment industry were still a stable institution.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Career specifics, like dry biographical information, can only convey so much. It’s a reasonable impulse to want to sum up a life in the wake of death, but with Lynch it feels especially misguided, or at the very least futile. Much like Jeffrey Beaumont being both detective and pervert, Lynch frequently embodied polar opposites. His work evinced a terminally unfashionable earnestness about the power of love, but at the same time it could also exhibit a mean streak for its own sake. Many critics have tried to pin down Lynch’s politics over the years, but he rarely fell along exclusively progressive or reactionary lines. (His vocal expression of solidarity with the trans community in The Return—“Fix [your] hearts or die”—was a powerful exception.) Despite attempts to retrospectively label him a sweetly sincere artist, Lynch was one of our greatest ironists; though he deployed the technique judiciously, he could easily mine comedy from the darkest of places, and his characters had the potential to be heroes or punch lines depending on the situation.

That inclination never invalidated Lynch’s palpable love of people, however, which remained sacrosanct and self-evident. His loyalty toward his regular collaborators was rewarded in kind, and he spoke of the characters he created as if they were his own flesh and blood. His fondness for archetypes (the Woman in Peril, the White Knight, the Devil Next Door) frequently brushed up against his penchant for complicating them simply because he understood that human beings are irreducible. Laura Palmer—Twin Peaks’ beating heart and the focus of its central mystery—was a devoted friend and community leader, but also an incest victim whose trauma at the hands of her possessed father drove her to addiction (to sex and drugs) and death. Lynch admirably insisted that none of these aspects negated each other; they were merely representative of a whole person whose public face and private behavior were forgivably at odds.

Lynch’s films are suffused with images or reminders of death, from John Merrick laying down for his final sleep in The Elephant Man to the various actors who gave posthumous (or soon-to-be-posthumous) performances in The Return, which often felt like a moving requiem for the director’s aging company of actors. His films emanate an almost religious respect for grief, and many reveal a persistent faith that people can pass into a harmonious, otherworldly plane beyond the mortal realm. It’s as though Lynch had spent a lifetime trying to grasp the meaning of such an elemental experience decades ahead of time.

In an interview with the BBC last year, Lynch said that he believed “life is a continuum, and that no one really dies, they just drop their physical body and we’ll all meet again, like the song says.” His diverse artistic legacy—the films, yes, but also his memoir, his avant-pop records, his furniture designs, and his two and a half years of Los Angeles weather reports on his official YouTube channel—bestows immortality anyway.

Lynch always belonged to a category of one, but the ongoing literal dehumanization of the popular arts—the active effort to remove people from them to satisfy an unquenchable demand for higher profits—makes him all the more vital as a creative beacon. He presented the full, uncompromised version himself on-screen, demanded nothing more than curiosity from his audience, and, in both life and death, received undying devotion from so many in return. What else could one possibly hope for from our brief time in this world?

More from The Nation

The Haunting of Delmore Schwartz The Haunting of Delmore Schwartz

In his Collected Poems, his verse becomes an index for a life lived between ambition, pain, and disappointment.

The Often Misunderstood History of the Soviet Dissidents The Often Misunderstood History of the Soviet Dissidents

In To the Success of Our Hopeless Cause, historian Benjamin Nathans sheds light on how the protest movement reinvented itself at key junctures and eventually to great effect.

The Unsettling Genius of David Lynch The Unsettling Genius of David Lynch

In his films, his TV shows, and his paintings, Lynch reminded us that all art gestures toward a world beyond the familiar and comforting.

The Introspective Club Hits of Jamie xx The Introspective Club Hits of Jamie xx

With In Waves, Jamie xx—whose real name is James Smith—has perfected what he explored in In Colour: an album full of searching tunes that can double as dance songs.

Can “Babygirl” Breathe New Life Into a Retrograde Genre? Can “Babygirl” Breathe New Life Into a Retrograde Genre?

The movie, starring Nicole Kidman, operates at the level of the female gaze. Its inversion of erotic thriller tropes leads to fascinating but, at times, tepid results.

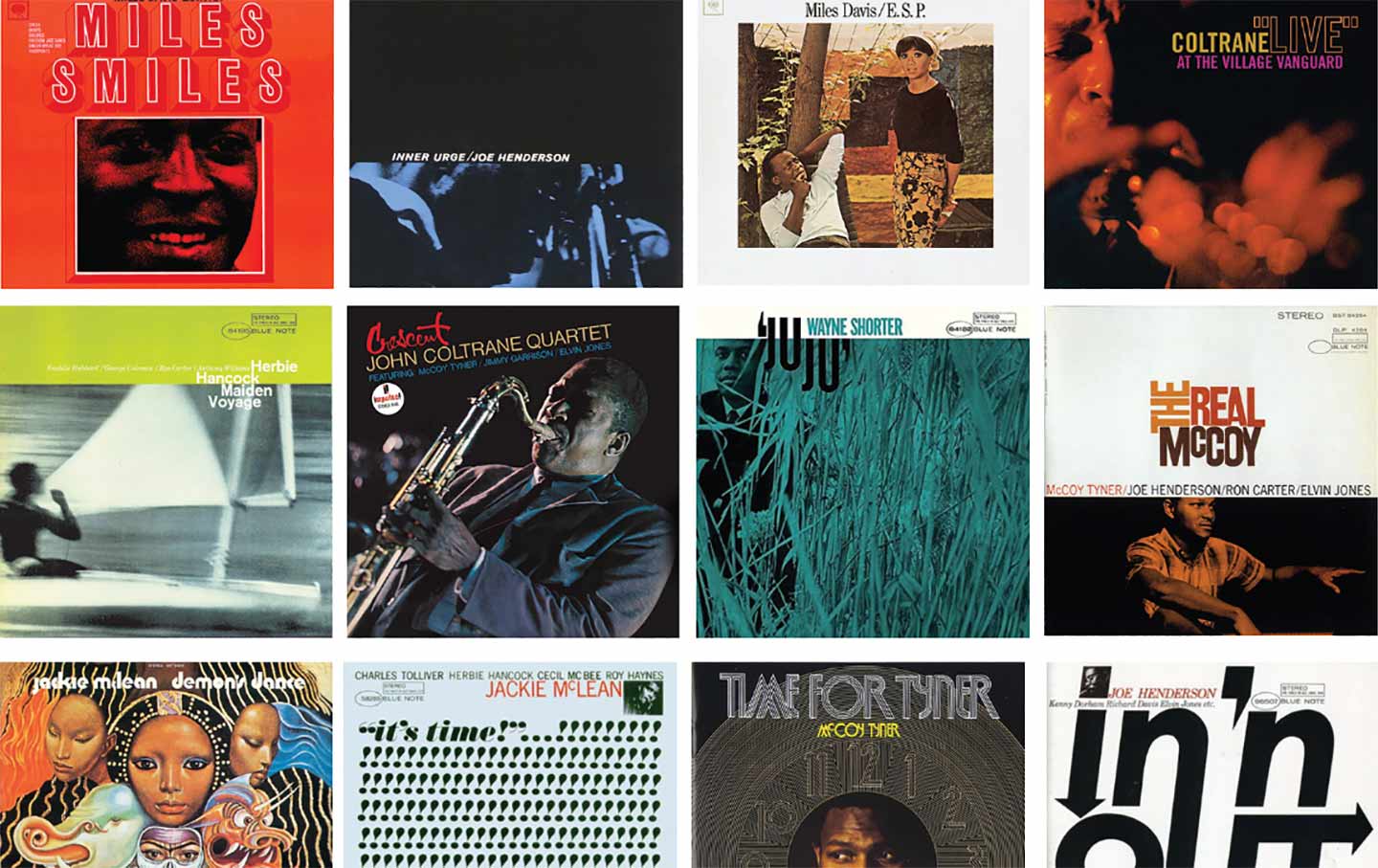

A Listener’s Guide to Jazz From 1964–1972 A Listener’s Guide to Jazz From 1964–1972

A selection of the best recorded examples of the otherwise mostly undocumented music heard in jazz clubs like Slugs’.