The Reckless Creation of Whiteness

In The Unseen Truth, Sarah Lewis examines how an erroneous 18th-century story about the “Caucasian race” led to a centuries of prejudice and misapprehension.

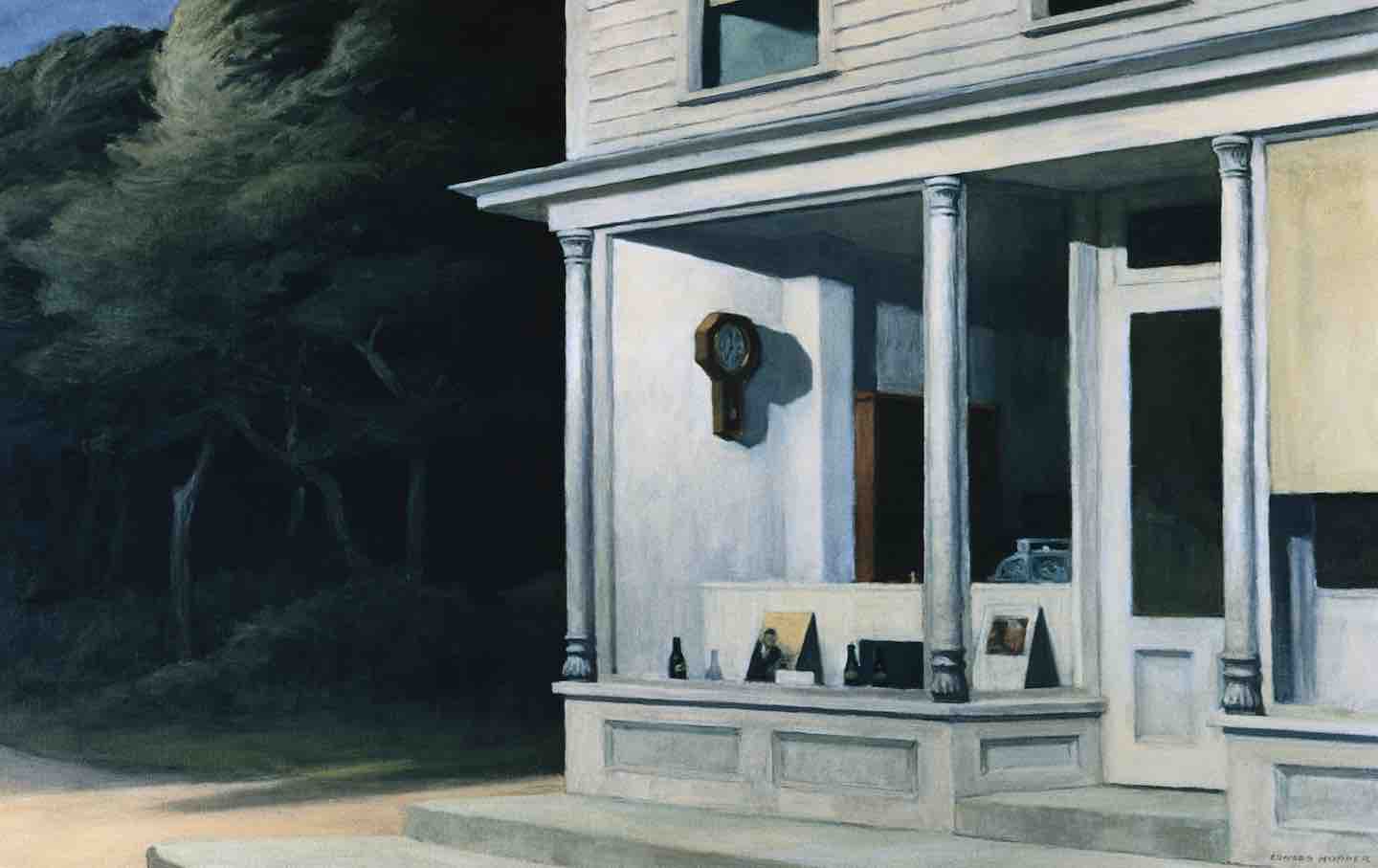

Mikhail Lermontov’s Memory of Caucasus, 1838.

(Fine Art Images / Heritage Images / Getty Images)

Americans have long been invested in an imaginary story: that whiteness stems from the mountainous region between Eastern Europe and Western Asia known as the Caucasus. In The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America, Sarah Lewis tells the story of the origins of the “Caucasian race” and the concealment of its discrediting in the early 20th century. Lewis has written a bold intellectual history, drawing from school atlases and encyclopedias, circus sideshows, yellow journalism, and presidential files to reveal the false foundations of ideas of race that continue to shape the United States.

Books in review

The Unseen Truth: When Race Changed Sight in America

Buy this bookThe Caucasus was identified as the homeland of the white race by the German naturalist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in his 1795 treatise On the Natural Varieties of Mankind, which was written to provide a more scientific footing for the notion of polygenesis: the theory that God created separate human races for different parts of the earth. Blumenbach believed that all living humans were descended from the family of Noah after they came stumbling out of the ark when it landed on Mount Ararat in the southern Caucasus. In his telling, God sent Noah’s darker-skinned sons off to other lands to begin the African and Asian races, while his lightest-skinned son simply remained in place. Blumenbach further pinpointed one local group, the Circassians, as the “purest” examples of the white race, on the basis of nothing more than travelers’ tales about the exemplary beauty of Circassian women.

Such ideas were eagerly adopted by American slaveholders, who wanted to think that the enslaved were a different, inferior type of human. But Blumenbach’s crackpot history moved from race-science arcana to headline news in the 1850s, when Americans became fascinated with the Caucasian resistance to Russia’s attempts to extend its territory southward. By the 1860s, Southern journalists frequently drew a parallel between America’s own War of Northern Aggression and the Caucasian resistance. In 1864, the Russians expelled hundreds of thousands of Circassians from their homeland. Many died before reaching a new, uneasy home in Turkey. The Caucasian War was a dark mirror, then, for those who defended the South in the Civil War: It revealed a possible dreadful future for the Confederates, who considered themselves defenders of the white race.

Yet increased interest in the Caucasus meant increased scrutiny of who exactly lived there. Americans began to acknowledge the diversity of ethnicities and religions in the Caucasus: a fragmented region composed of Persians, Ottomans, Georgians, Yazidis, Jews, and even Buddhist nomads. Already by 1855, the abolitionist and physician James McCune Smith wrote about the attempts of race scientists to “seek paternity” for the white race in Arabia after realizing that the people of the Caucasus “are, and have ever been, Mongols.” “Keep on, gentlemen,” Smith commented with prescient sarcasm. “You will find yourselves in Africa, by-and-by.”

George Kennan, an explorer and one of the most popular American public lecturers in the late 19th century, was probably the first American to travel the length of the Caucasus Mountains and was certainly the first to make a living talking about the “kaleidoscope of ethnic groups” he had seen there. The Caucasus was revealed to be similar to the United States after all, in that both populations were a “heterogeneous collection of the tatters, ends, and odd bits of humanity.”

We can see Americans working out the issue of the relationship of the Caucasus to whiteness with the help of P.T. Barnum, who debuted a new attraction at his American Museum in New York City in 1864. Advertised as an “extraordinary living FEMALE SPECIMEN,” Zalumma Agra trotted onstage with her hair teased straight up, as if electrified, while Barnum recited her “biography,” describing her birthplace in the Caucasus and how she had fled from the Russians. Zalumma was the first in a line of performers in Barnum’s and then rival establishments, known as “Circassian Beauties.” In reality, none of them had set foot in the Caucasus: They were local performers, often Jewish or Irish women whose hair had been stiffened with the help of coatings of beer. Zalumma herself was born Johanna Nolan—although, in a truly American twist, Census records show that she kept her new name even after she no longer performed for Barnum.

Lewis argues that Barnum’s chicanery was part of the point: Audiences enjoyed the puzzle of guessing whether or not the women were who Barnum claimed they were. The Circassian Beauties functioned, Lewis argues, “as an optical exam for a country consolidating its rules of visual racial discernment.” Fittingly, souvenir photographs from the 1870s show African American and albino women portraying Circassian Beauties, making even more antic comment on the concept of just who was Caucasian.

The fascination, though, proved to be long-lasting. In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson asked a major general on a trip to Armenia to render a report on “the legendary beauty of the Caucasus women.” Wilson, who saw America as a “great White nation,” was considering whether the US should arm the Armenians in their fight against the Turks for autonomous rule, since he considered the people of the Caucasus to be “of our own blood.” The cooperative British chief commissioner of Transcaucasus gathered 70 women for inspection, but a stroke left Wilson incapacitated before he could receive his deputy’s conclusions about this curious beauty pageant.

By the turn of the 20th century, however, fewer Americans believed that all white people descended from a specific location. The new looseness of whiteness turned out to have crucial advantages. Unmooring race from a definite place made whiteness an imagined community into which new populations, such as Irish and Italian immigrants, could be welcomed when this proved politically expedient. But a “whites-only” segregation regime was hard to administer when the authorities found it difficult to define just who exactly was white.

Lewis argues that “visibility is at the core of politics” in America, where what matters most is whether your fellow citizens see you as a “fully empowered subject.” The Unseen Truth fits into a tradition of arguments made by thinkers like Frederick Douglass and Freeman Henry Morris Murray about the importance of representation to race and politics. (One of the core contributions of the book is Lewis’s contextualization of the work of the underappreciated Murray, a writer, activist, and civil servant who fought against Wilson’s expansion of segregation.) Lewis adds an important insight: that the grinding scrutiny of the supposed inferiorities of Americans of color was a rearguard action fought after the collapse of any coherent idea of a “white race.” Upholding discrimination meant jumping from one delusion to another.

When Lewis traveled to the Caucasus in 2019, hardly anyone she met knew that “Caucasian” could be a synonym for “racially white.” Only the handful of Caucasians she met who had traveled to the United States understood their unintended recruitment into whiteness, and they learned of their status almost accidentally—filling out an immigration form, or in a chance encounter with a white supremacist who treated the visiting Caucasian “like a god.” Lewis sees the idea of the Caucasian race as a “haunting” that still manages to convince some Americans that there is some scientific validity to the idea of a unified white race. Her book aims to put that idea finally to rest.

Still, one might bemoan just how rapidly the idea of whiteness has recovered from past attacks on its intellectual underpinnings. Facts do not seem to matter when the fiction is so convenient. But at least, as the current uproar over critical race theory shows, teaching the public about the evolution of the concept of race is treated as enough of a threat to make the endeavor seem worthwhile.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation