Vigdis Hjorth and the Novel of Ugly Love

In If Only, the Norwegian novelist distills a story of romance into all its private discomfort and claustrophobia. Its intense ambivalence in regards to love feels truer to life.

Summer Interior by Edward Hopper, 1909. Located at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

(VCG Wilson / Corbis via Getty Images)

The Norwegian novelist Vigdis Hjorth is skeptical of conclusions. She knows that readers always know that the end of the story, happy or tragic, is not quite like life: There are always too many loose ends, continuations. We accept that a narrative is a fragment chipped off from the bulk of experience, polished into something pleasingly separate. In Hjorth’s novels, the women she writes about face problems that are difficult to resolve—a death in the family, a traumatic childhood, the endless grind of work—and which may be unresolvable. That these problems are ordinary makes their failure to surmount them even more painful. Hjorth is fascinated by the stuckness of her characters. The real problems never really disappear—the novel may end because we’ve turned all the pages (or the writer runs out of willpower), but her books are composed of echoes and loops. Things happen again, even after we declare them over. Hjorth tests the idea that the novel may never end either, if it is to truly deepen its relationship to life. In her hypnotic novel If Only, recently translated by Charlotte Barslund, the problem that its characters face is among the thorniest of all: the problem of love.

Books in review

If Only

Buy this bookIda is a young playwright and editor, just beginning her career. She is also a wife and the mother of three children, but her home life leaves her feeling unfulfilled. Arnold is an older, established academic, a specialist on Bertolt Brecht, and a serial philanderer. The pair meet at a literary seminar and have a one-night stand, but Ida gets hooked and can’t stop thinking of Arnold, even as it becomes clear that he is hardly perfect. After sex, he absent-mindedly calls his wife, and Ida tells herself “it doesn’t matter.” Arnold makes no promises, saying he can’t handle another breakup, but his flirtations with Ida don’t stop. Through Ida’s effort and persistence—cryptic letters back and forth, years of pining, the tiresome urge to ask every acquaintance what they’ve heard about him—she wins Arnold and receives the gift of an equally possessive passion. From the start, it’s clear that Ida and Arnold are in for mutually assured destruction.

Their affair is a vortex of private logic, breaking apart their previous families and embarking on an amour fou that lasts several years. The relationship is poisonous, but how can they avoid the desire that pulls at them more strongly than anything else? For Ida, “it makes no sense to anyone but the lovers. It can only be expressed in their new language for two, shared only by them.” And when Ida learns that Arnold has slept with another woman, outrage bends inevitably toward rationalization: “Consciously or subconsciously, he’s doing this to come to me.” Later, when Arnold tells Ida that he’s “cursed” (“I have to torture every woman who falls in love with me”), we must take him at his word. If Only is Ida’s narrative, presenting “her side of the story,” but this idea of the woman’s testimony, lifting her truth out of the tangle of experience, is only one subsidiary part of Hjorth’s project. As are questions of the rightness or wrongness of Ida’s and Arnold’s actions, or even why this overpowering need for each other happened. Description and detail are restricted, with the emphasis given to dialogue and anxious rumination. If Only reduces the relationship to something narrow, even claustrophobic—that is, the unfiltered relay between two people who have decided to become inseparable: all the infidelities and drunken shouting matches, but also the mornings spent in bed, the days of writing together in the same room, the long evenings lasting as long as the pair believe “they will never tire of it, they will carry on, carry on, carry on.”

Doomed love is one of the oldest stories around. But what makes Hjorth’s use of the convention distinctive is her dedication to its repetitions. The arc of Ida and Arnold’s relationship is not graceful or even storylike. It begins with longing and proceeds through vomit, smashed plates, lies, and betrayals; eventually, Arnold physically abuses Ida, something that the novel spends relatively little time with. Anything that might seem special or pivotal in the relationship becomes one more item in the litany. Even moments of happiness repeat themselves: Ida and Arnold often travel abroad (to avoid prompting gossip in the small world of Scandinavian letters) and find themselves “getting married” repeatedly in order to be toasted and pampered by waiters and bartenders. Hjorth’s focus, then, is on all those moments lined up together, sparing the reader no squabble between them: Should Ida go on a trip to Japan and leave Arnold alone in his jealousy? Will sleeping with other people keep their sex life going? Hjorth’s insistence on documenting each turn of the relationship, even as she risks replicating the tiresomeness of real life, is engrossing: She forces us to stay inside the relationship and hold the couple’s pleasures and pains, at least for a few hours. Past judgment, she tries to reenact the passion, to experience again all its highs and lows.

Hjorth’s novels draw from lived experience and inner pain, but they are not simply unedited diaries. Her work is not defined by the plotless drift we’ve come to expect from some contemporary novels; her protagonists have strong desires and seek to satisfy them. There is also always a formal ingenuity, set down with a light touch, that regulates the pileup of events. If Only begins in the first person with a kind of prologue: “The curtain rises and here I am!… Secret signals to the girl I was twenty years ago. I lean back and tentatively smile, I act as if she were watching me.” This I-voice quickly recedes as the storm of Ida and Arnold’s relationship grows, and the reader nearly forgets—until some stray comment from the wiser Ida intrudes—that we, too, are looking in from afar, like an audience member in the back row. At certain points, the narration chimes in on the repetitions themselves, asking: “Is it as tiresome to read as it is to write? Won’t something happen soon?” These few interjections puncture the relationship’s fog. They don’t dispel the reader’s absorption entirely but add an intermittent poke in the eye against past self-seriousness, and perhaps some encouragement to the reader to keep going.

As in Hjorth’s other novels, dramatic theater is a persistent interest. This is felt in the form, which is heavy on dialogue, as well as the content: Arnold is a scholar of Brecht, working on translations of his erotic poems, and Ida is drawn to Ibsen, the ultimate Norwegian literary father figure. When their love is at its peak, they write a play together. Maybe the reader is prompted to compare these two ideas of theater. On the Ibsen side, an impulse to faithfully represent intimacy—people struggling to understand themselves and their loved ones, and the intensity those clashes of the psyche unleash. On the Brecht side, a willingness to step beyond the frame, point back at what we already know, and question if this is the only way that things might be staged. Hjorth darts between these two perspectives, suggesting that they could coexist. The “drama” of our emotional life is often all too conventional, but Hjorth’s books insist that we sell the experience short, both in our willingness to chronicle it unsparingly and in our ability to reconsider it with distance.

At one point, Ida, under enormous emotional stress, begins psychoanalysis—another kind of theater for staging psychic life. Her therapist is uninterested in her entanglement with Arnold, seeking to unearth the problems of her childhood (for Hjorth, another recurring subject). For Ida, psychoanalysis fails: It threatens to interrupt her attachment to Arnold, and so she abandons it. Hjorth is no stranger to Freud, and If Only is, at its core, a novel of “repetition compulsion,” Freud’s term for the patient’s need to stage a traumatic moment again and again in an attempt to master indirectly what remains repressed. The nature of Ida’s and Arnold’s traumas are never fully explored. Whatever made them the way they are stays hidden; they would not act the way they do if they understood. After another fight, Arnold tells Ida that he repeats his parents’ old phone number to calm himself down, and she replies, “It points to your childhood”—acknowledging the truism while jokingly admitting that it can’t really explain anything in the moment. Instead, we are kept hermetically inside their repeated attempts to find and master pleasure—or to self-sabotage. Maybe, Hjorth suggests, there are wounds that can’t be healed inside the novel.

Hjorth is usually described as a practitioner of “reality literature,” a Scandinavian tradition that sometimes gets her casually lumped in with her fellow Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgaard. Thanks to recent translations of authors like Tove Ditlevsen, English readers are now better able to see a lineage of writing about women—their position and struggle in a society of stultifying conformity—that extends back decades. (And while we might place Knausgaard, Ditlevsen, and Hjorth in a broader tradition of so-called autofiction, perhaps it makes more sense to see fiction’s permeability with life as an essential tool for writers rather than as a coined genre.) In Hjorth, the relationship to “real life” is true, but trivially so. Your knowledge of the late 20th-century Norwegian literary scene may grow if you connect Arnold to a real person, but you may also be on the wrong track. As time passes, only the forms remain, and Hjorth specializes in life’s subtle flavors and rhythms, things that would escape most authors’ imaginative faculties, which can tend unconsciously toward the generic.

Hjorth is the author of more than 20 books and has become one of Norway’s most celebrated writers for these unsparing recombinations of her personal life. While a novel like Long Live the Post Horn! (2012) demonstrates her range—it’s a dark workplace comedy (centering on a colleague’s suicide) as well as a meditation on what we owe to one another in a corporatized world—Hjorth is often focused on the family. In Will and Testament (2016), her most famous novel, an inheritance dispute among siblings leads to a confrontation over their father’s abuse of the narrator, Bergljot, something most of the family ultimately cannot accept. Will and Testament was a scandal and a sensation in Norway; it contains plenty of hints that relate to Hjorth’s life, though she has been steadfast in declaring the novel as fundamentally separate, and even resulted in a counter-novel written by one of her siblings. Like If Only, it compels precisely through its resolutely “ordinary” structure, unfolding over phone calls, angry e-mails, smudged memories, and executor meetings. The novel stages a trauma, or at least its aftereffects, but recognizes that it’s not really something that Bergljot can really “get over” no matter how the will turns out (Bergljot herself is barely interested in who gets what). The narrative’s flow feels truthful because it doesn’t force change upon its protagonist. In turn, the novel stimulates the reader’s curiosity—although there is serious terror inside its everydayness—and like a real family story, it has no neat way to tie itself up.

In Is Mother Dead (2020), Hjorth’s previous novel, a similar preoccupation is taken up by the narrator, Johanna. A successful Norwegian artist who has been ostracized by her family, Johanna returns to Norway for a retrospective. Her most famous painting is an image of mother and child, obliquely described, that has apparently shocked and offended her family. One drunken evening, Johanna calls her mother and receives no response. This escalates to Johanna texting her mother, writing her letters, looking her up online, until she eventually finds herself clandestinely following her. Johanna’s mother will not yield, try and try as Johanna might. In the end, an answer is supplied, but it cannot really explain Johanna’s grief—it is merely a placeholder. The sense of loss continues on after the novel’s end.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In recent years, much has been written about the “trauma plot,” after the critic Parul Sehgal’s coinage in an essay in The New Yorker. In her description, the trauma plot is something backward-facing: It “does not direct our curiosity toward the future (Will they or won’t they?) but back into the past (What happened to her?).” The result is a kind of flattening of fictional narratives, as the original instance of damage becomes the key that unlocks the story. If everything has been decided in the traumatic beforehand, Sehgal wonders, why bother reading what happens after? Hjorth is a writer of trauma, but she refuses that easy causal linkage. Trauma is persistent in life, she seems to say, and the toll it exacts can’t be ignored. But she decides to foreground the story’s present over past or future—she is fascinated by our attempts to overcome a condition that feels fixed, always failing but resolved to try again.

Can If Only’s journey into codependency show us something more than the awful blow-by-blow? Vivian Gornick, in her classic essay “The End of the Novel of Love,” wrote:

We loved once, and we loved badly. We loved again, and again we loved badly. We did it a third time, and we were no longer living in a world free of experience. We saw that love did not make us tender, wise, or compassionate. Under its influence we gave up neither our fears nor our angers. Within ourselves we remained unchanged. The development was an astonishment: not at all what had been expected. The atmosphere became charged with revelation, and it altered us permanently as a culture.

Gornick argues persuasively that the contemporary novel had moved away from romantic love as a central plot device, as it no longer was a catalyst for self-knowledge. For Gornick, “love as a metaphor is an act of nostalgia, not of discovery.” Yet despite Gornick’s brilliant analysis of love in the novel, it’s not so clear that we’ve moved past it. Maybe this is our own literary repetition compulsion—even as we crave new forms, we might still be unable to truly get over, or even name, what ails us. We are forced back into convention, it seems, even for practitioners who are skilled and canny; at the moment, Sally Rooney’s love stories rule the literary world. What for Gornick was a failure of a genre is for Hjorth precisely the point. She forces us to think through our paralysis, rejecting an idea of literary “progress”—her work is a kind of avant-garde between the lines of the mundane.

If Only’s omissions are telling, too. For Ida, channeling Arnold’s romantic Brecht view of the world—“He likes tramps and rebels and drunks and people who kill themselves. Those who shock the middle class, he likes outsiders and he likes female students. He likes poor people and revolutionaries, mutineers, fighters on barricades, Communists, rabble-rousers, and there are few of those”—their relationship becomes a total rejection of the outside world. Its insularity points to something else: an unease with conventional life, the familiar routines of career and family, a political world where all meaningful choices seem foreclosed. The lovers of If Only run away from normalcy because it saps life of its vitality—the affair may be a broken vessel, but it’s a glimmer of a life worth living, even if it can’t be captured yet. Ida reflects at one point that “when she was a child she would get palpitations from the sheer joy of being alive. How far away that seems now, how insane.” The problem is not a question of why Ida and Arnold need love so badly. Instead, it’s why is their whole world so deadening?

Sometimes it’s hard to say why we finally leave a bad relationship. It could be one fatal transgression, but more often it’s an accumulation of experience, a wisdom that, when it emerges, almost seems to come from somewhere else. In Søren Kierkegaard’s short book Repetition, published after his own failed marriage plot, Kierkegaard’s literary persona Constantine Constantius tells us that repetition is the essence of life: “What would life be without repetition? Who would want to be a tablet on which life wrote something new every moment, or a memorial to something past?” As opposed to recollection or hope, to embrace life’s endless recurrences is what it means to really live—revelation will come to us at a time not of our choosing. It’s certainly not Freudian thinking, but Hjorth is also a reader of Kierkegaard and, I think, prefers him. What could be more difficult than staying in the moment, to stand with what hurts us most, what excites us most? What choice do we have but to move toward the passion that we cannot quell?

More from The Nation

The Dubious Return of the Brutalists The Dubious Return of the Brutalists

Why the stark 20th-century architectural style is back in vogue.

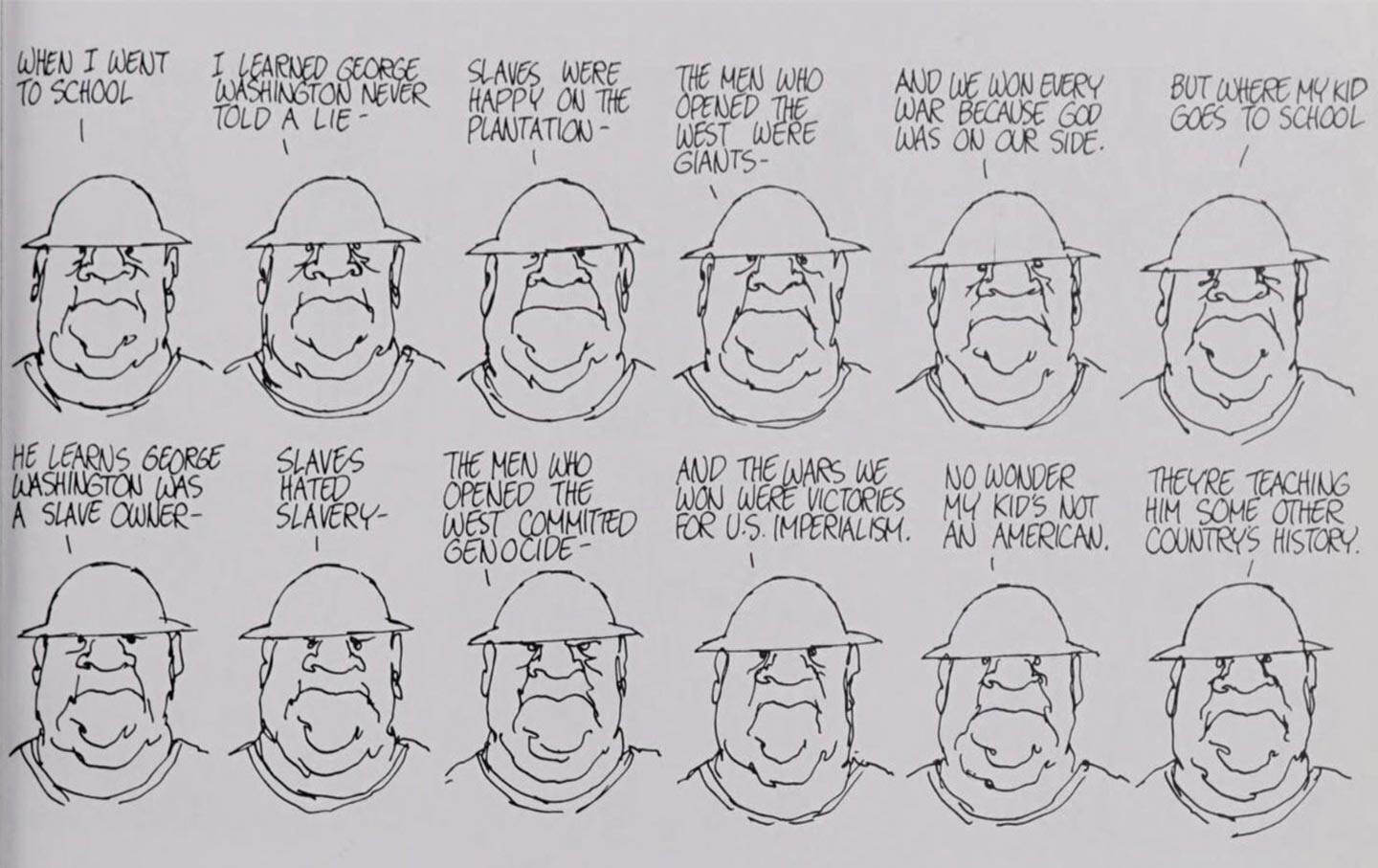

Devastating Empathy: Jules Feiffer, 1929–2025 Devastating Empathy: Jules Feiffer, 1929–2025

The cartoonist and writer proved that the deadliest skewering is informed by understanding.

The Art of Reading Like a Translator The Art of Reading Like a Translator

In The Philosophy of Translation, Damion Searls investigates the essential differences—and similarities—between the task of the translator and of the writer.

The Reckless Creation of Whiteness The Reckless Creation of Whiteness

In The Unseen Truth, Sarah Lewis examines how an erroneous 18th-century story about the “Caucasian race” led to a centuries of prejudice and misapprehension.

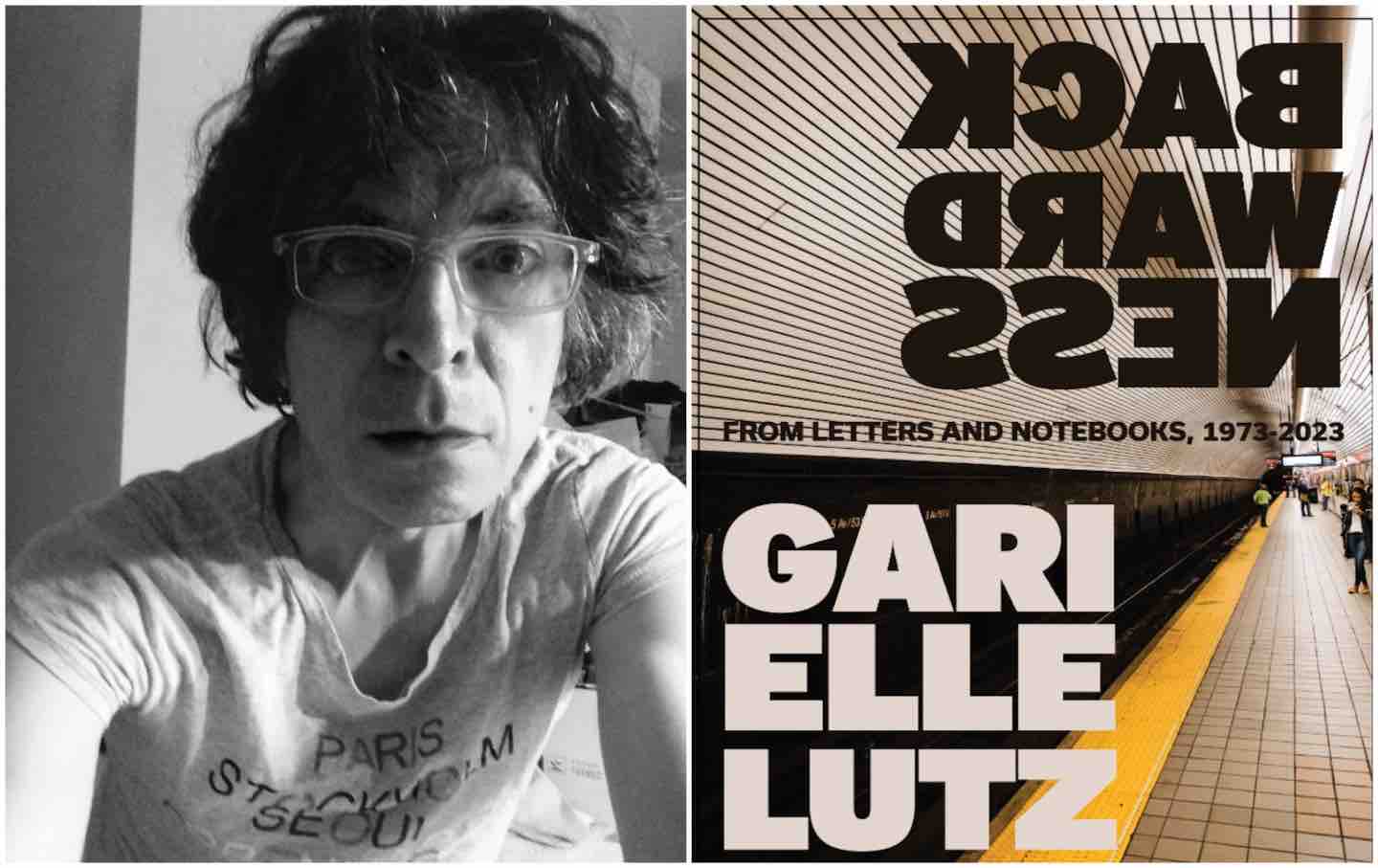

The Polymath of Pittsburgh The Polymath of Pittsburgh

Garielle Lutz is one of America’s great writers. Why has her literary genius gone unnoticed?

CNN Surrenders to Trump CNN Surrenders to Trump

The corporate media’s commitment to fighting autocracy proves fickle.