Triage

The Pitt and the rise of a new era of hospital dramas.

“The Pitt” and the Rise of a New Era of Hospital Dramas

In a frenzied medical drama, the limits and problems of the healthcare system became the basis of the show’s plot.

The Pitt marks a telling return to a style that long dominated television. Set in the Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Center, Max’s popular new show proves that the frenzy of an overwhelmed emergency department can feel comforting and familiar. TV, after all, once abounded with ensemble shows about doctors, lawyers, cops, or other skilled professionals going about their daily routines, solving problems in ways that only they can, while also dealing with the complications of their messy personal lives. A murder is committed, an innocent man is wrongly prosecuted, a sick person comes in with symptoms that don’t make sense—a problem needs to be resolved. They are narratives powered by mystery, the search for information and its uses. By the end of every episode, the case will be closed.

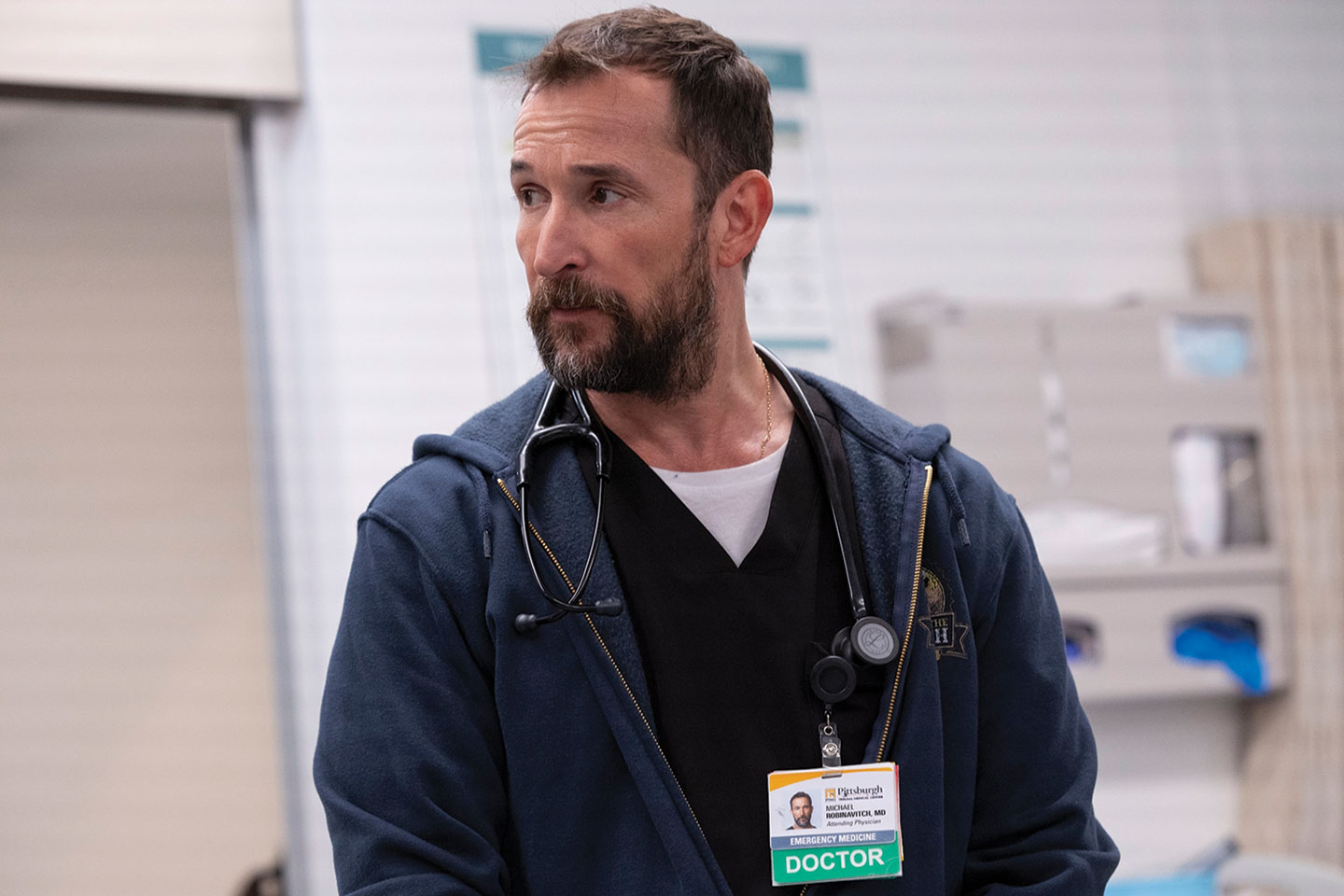

There are fewer medical procedurals these days, and while cops and lawyers haven’t left TV, it’s only been over the last decade or two that their cases have tended to stretch over an entire season. The Pitt, on the other hand, is a throwback to an earlier age: The characters’ own evolution may progress slightly, but the cases are constantly replenished; one mystery may be shelved but another escalates, a patient’s condition worsens or a missing fact comes to light. The dynamism of the series is not only psychological but also physical. Though not a sequel to ER, The Pitt inherits that show’s high-octane pace, and some of the beats will feel familiar: We see the world through the eyes of new interns and medical students; paramedics wheel in patients, announcing their condition as a doctor and nurse banter over the body. The Pitt also inherits two ER veterans at the helm of the series and one of its lead actors, Noah Wyle, whose wide eyes and long face introduced us to Chicago’s County General in 1994.

But The Pitt is not pure nostalgia for that lost heyday of medical procedurals. There’s a world-weariness in this revival, a newfound sense of anxiety and trauma created by the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and austerity’s walls pushing in on the medical staff and patients—the chaos of the emergency room remains, but its causes and sense of inevitability are more clearly in the picture. Wyle’s face alone connects us to the past and alerts us to all that has changed in 30 years. He’s wizened and weary but still warm, and as the attending physician, he keeps the Pitt, and the show, running. There’s interpersonal drama—doctors sniping at each other or arguing over the correct course of action—but because of the show’s real-time approach, the focus is on medical problems, not character development. ER was full of workaholics, but they still went home at the end of their shift. In The Pitt, we see only people on the clock, overworked, under-resourced, and stretched thin. They can only fix the body in front of them.

At times, The Pitt’s approach to storytelling can feel like quantity over quality. In the first episode, we are introduced to six doctors, two medical students, and five nurses. By the end of the first two hours, we have seen at least two dozen patients in various conditions, from asking for a sandwich to arriving in the ER dead. At times, it can be hard to keep up: With so much coming at us and an ensemble this big, the characters remain types—doctors are given a defining trait or two or a noticeable flaw, and patients are presented as case studies, stand-ins for a malady or a social issue. Just as a physician making a diagnosis tries to see the illness through its symptoms and not the individual patient, The Pitt mostly deals with the world by abstracting it, leaving specificity outside the hospital’s doors.

The character whose outline gets the most shading is Wyle’s Dr. Michael “Robby” Rabinovitch, the attending physician who leads and guides the department. When we meet him, it’s on the anniversary of his mentor’s death, an early pandemic loss that clearly still affects him, though Robby brushes off anyone’s concerns. Unresolved grief is not exactly a unique trait for a television character, but Robby’s loss serves poignantly as a formal feature of the show; his flashbacks are really the only moments in which The Pitt departs from the immediacy of the here and now. It’s also the first day for a few new faces in scrubs: We meet Melissa, a second-year resident, awkward and earnest; Trinity, an arrogant intern; and Whitaker and Javadi, a pair of med students—the first a hapless farm boy and the other a prodigious nepo baby. Robby takes them on his rounds to visit patients, simple cases that set the stage before the real tragedies are wheeled in.

The mentors of these new scrubs are also quickly sketched. One doctor is pregnant but keeping it a secret; one second-year resident is much older than her peers and wants to tell you about her 11-year-old son. One resident is the cynical hotshot, with little patience for sentimentality, and another is the one who cares too much. Because the show moves so quickly and in so many directions, simplicity is the only thing that keeps these characters from blurring together. Each has a hand in the effort to manage the overflow of pain and confusion that continually threatens to overwhelm the hospital.

The Pitt’s frenzied style is not just a throwback to ER but a temporal approach that draws from a different popular network drama: 24. Each episode chronicles 60 minutes in a 15-hour shift at the hospital, which means that cases aren’t neatly resolved by the end of each hour but are woven across multiple episodes. Tellingly, even the patients’ deaths linger as their family members and caregivers navigate a medical system that doesn’t know what to do with loss. An older man’s grown children slowly come to terms with his passing; the parents of a student who overdosed demand more tests; a med student loses a patient who seemed fine just a moment ago. Everything happens so quickly. In the flashbacks to his own mentor’s passing, Robby is seized by harrowing memories that drag him back to the early weeks of the pandemic. When a brother and sister say goodbye to their dad, the camera stays on Robby—he struggles to compartmentalize his own grief, but the walls will not hold.

The fact is, when someone is wheeled into the Pitt, they and their loved ones are almost certainly in for the worst day of their lives. Everyone at the hospital is trying to do their best, but they don’t really have the time or the beds to do the work they want to do; the onslaught of cases is overwhelming. In ER, the economic and systemic issues that hospitals face came up occasionally—the second-season finale, for example, tackled the inhumanity of the health insurance industry, leading a major character to quit on the spot—but in The Pitt, it’s a central concern. In the first episode, Robby has to fend off Gloria, a callous hospital administrator who only cares about high patient satisfaction scores, efficiency, and the bottom line. The show constantly cuts back to the waiting room, which is chaotic and bursting at the seams.

Robby tries his best in the face of austerity and profit maximization. His department’s doctors and nurses do what they can while trapped in a system that often has little interest in the health or care of its patients. And even when he’s faced with a difficult dilemma, Robby always tries to make the human choice—for example, he makes a split-second call to save a patient in lieu of waiting for the test results. He fudges the numbers on an ultrasound so that a 17-year-old girl can get the abortion she needs. A mother worries herself sick because she thinks that her son could become the next misogynistic school shooter, and Robby has to decide whether to alert the police or try to save the kid from himself.

It’s to the show’s credit that it embraces rather than avoids some of the largest healthcare issues of our time. These doctors and nurses deal with fentanyl overdoses, injuries from hate crimes, limited abortion access, and unhoused people who can’t afford medication. Because a visit to the emergency room is often a person’s choice of last resort, the ER is full of people already marginalized by society. Compartmentalization is failing Robby, but it’s failing medicine as well—any insight into the Pitt’s central struggle also requires seeing beyond the hospital’s walls.

One takeaway from The Pitt is that no matter how heroic the doctors and nurses and physician assistants are, they cannot fix the world; they can only try to fix the body in front of them. When Robby reaches out to the boy whose mother fears he may commit violence against women, the boy runs out of the hospital, and Robby can’t follow him. Despite the show’s title and some B-roll footage in the first episode, this is not The Bear for Pittsburgh. Even as we watch these medical professionals in their constant and sometimes horrifying scramble to save their patients’ lives, we don’t see much of the city, only symptoms of its sickness.

Foucault once described the medical gaze as a kind of trained seeing that removes the inessentials of a patient’s life story from the equation. In order to identify the illness, the physician “must subtract the individual,” leaving behind the symptoms and the differences that distinguish one disease from another. Often in the series, we see the doctors being given a brisk summary of the necessary facts: “Nick Bradley, 19. Found unresponsive by parents. No meds, no allergies. On arrival, he was barely breathing with pinpoint pupils, bradycardiac at 38.” The ER reduces people to that level of abstraction, patients and doctors alike.

In the series, the (fictitious) Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Center is a teaching hospital, and sometimes it feels like The Pitt is also trying to teach us: Each case exists for the moral attached to it, like the sickle-cell patient who creates a teaching moment for Whitaker or the trans woman whose name Javadi changes in the system. Individually, these cases can feel stilted, like thought experiments brought to life, but over time they coalesce into a larger story, painting a portrait of a medical system stretched to its very limits. This can feel tedious in some instances, illuminating in others, but the show’s hallmark is its momentum. One patient leaves but another arrives; one patient gets better but another gets worse. There is always someone to save, and the minutes tick by, then the hours. There is always a body in the next bed and 50 more in the waiting room.

More from The Nation

The Uncomfortable Genius of Mike Leigh The Uncomfortable Genius of Mike Leigh

In “Hard Truths,” Leigh reminds us that a family dinner can tell the story of a whole society.

Henri Bergson’s States of Change Henri Bergson’s States of Change

Why did one of the early 20th century’s most famous philosophers go out of fashion?

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past

The Pakistani qawwali icon sang words written centuries ago and died decades ago. He’s got a new album out.

The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish

Sure, it’s a dog whistle for “retvrn” types and the results are tacky—but that’s not the worst part.

The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker

Walker’s new installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art offers us visions from both the past and future.

A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation

Khawla Ibraheem’s play Knock on the Roof examines how the Israeli military terrorizes Palestinians in their most intimate and private spaces: their homes.