Parents and Children

The uncomfortable genius of Mike Leigh.

The Uncomfortable Genius of Mike Leigh

In “Hard Truths,” Leigh reminds us that a family dinner can tell the story of a whole society.

A spring morning on a quiet street in suburban North London. Inside an immaculate—indeed, compulsively clean—house, a middle-aged Black woman named Pansy (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) wakes up screaming. What was her nightmare? Does she live one? Could she be one? Hard Truths, Mike Leigh’s first film in six years, has a title that lends itself to multiple meanings and a protagonist whose complexity invites them.

Approaching his 82nd birthday, Leigh is not only the finest living British filmmaker but also the most Dickensian. Sensitive to social inequities and somewhat didactic, he is deeply invested in what George Orwell termed Dickens’s “cult of ‘character’”—or, as Leigh would put it, “character actors.” He populates his world, nearly always London, with a vivid assortment of creepy loners, nutty foreigners, sullen slugs, grotesque strivers, sloppy drunks, alienated teenagers, and malcontent misfits, along with a measure of sturdy, cheerful salt-of-the-earth types.

Although clearly a man of the left, Leigh (like Dickens) is less interested in society than human nature. Some of his characters are great creations: Johnny, the nihilistic, motormouthed autodidact of Naked; the eponymous warm-hearted abortionist in Vera Drake; Poppy, the relentlessly upbeat kindergarten teacher who animates Happy-Go-Lucky.

A student of socialist realism might term Poppy an offbeat “positive hero,” innately attuned to the common good. That’s not Pansy, played by Jean-Baptiste with agonized conviction. An antipode to the ever-cheerful, naturally altruistic Poppy, Pansy is paranoid, pessimistic, and obsessive, an acid-tongued kvetch given to hilarious if humorless invective. Five minutes into Hard Truths, she’s bludgeoning her silent husband and son with a diatribe against pet dogs whose owners swaddle them in coats, babies with pockets in their onesies, and neighborhood do-gooders: It’s impossible to go in and out of the supermarket, she rages, without encountering “grinning, cheerful charity workers loitering out there demanding your hard-earned cash.”

Dickens mined his childhood trauma for material. So too Leigh, who has spoken of the family “screaming matches” he endured as a boy growing up in a working-class suburb of Manchester and in an observant Jewish home, the son of a demanding, opinionated doctor who, Leigh has said, not only discouraged his interest in drawing but prescribed psychotherapy to cure his artistic ambitions. Family dinners, Leigh told an interviewer, gave him “a lifetime’s ammunition” for his filmmaking.

Leigh made his first feature, a comedy-drama provocatively called Bleak Moments, in 1971 and his second over a decade later, when, after extensive work in British TV, he emerged with a trio of seriocomic, actor-driven features, all dealing with the domestic lives of working-class and déclassé Londoners. First came Meantime in 1983, followed by High Hopes in 1988, and Life Is Sweet in 1990. Each explicitly or implicitly criticized Margaret Thatcher’s supply-side economics, but Leigh’s praxis was at least as radical as his politics. His films, like those of the pioneering independent John Cassavetes, were genuinely experimental: Their scripts were founded on collective improvisations and refined over weeks or even months of rehearsals, a process that, in describing her work in Hard Truths, Jean-Baptiste compared to psychoanalysis.

Naked, Leigh’s bleakly funny, often repellent 1993 masterpiece, dusted off a well-known British film trope: the “angry young man.” Embodied by David Thewlis, the film’s newly homeless anti-hero rants his way to the end of the night, sexually exploiting whatever women are luckless enough to cross his path. Thewlis won the acting award at the 1994 Cannes Film Festival, while Leigh was named best director and became a festival fixture. His next film, Secrets & Lies, was a character-driven dramatic comedy in which a Black adoptee (Jean-Baptiste in her first real movie role) discovers her white birth mother; it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and reaped five Oscar nominations.

Through the 1990s and into the 21st century, Leigh continued to make semi-comic class-conscious ensemble films—all, save Vera Drake, set in present-day London. At the same time, Leigh expanded his oeuvre to include British “heritage films.” The unexpected and delightful Topsy-Turvy told the story of Gilbert and Sullivan creating The Mikado; Mr. Turner rewarded Leigh regular Timothy Spall, usually an amiable troll, with the role of the visionary 19th-century painter J.M.W. Turner; Peterloo, the most ambitious (and, by far, the costliest) production of Leigh’s career, essayed the historical epic, complete with authentic Lancashire dialect.

Jousting with British cinema’s imperial knights (Sir Richard Attenborough, Sir Carol Reed, and Sir David Lean), Leigh deployed digitally enhanced crowd scenes to re-create an early-19th-century massacre of reform-minded working-class activists in a field outside of Manchester. The bloodbath inspired “The Masque of Anarchy,” Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem of political protest, more than once quoted by Jeremy Corbyn: “Ye are many—they are few.” The movie was a critical success and a financial failure.

Having made a large-scale costume drama, albeit one focused on the English working class, Leigh has returned to the character-driven social realism of his earlier films. Not that Hard Truths is a comfortable film or a small one: However intimate, Leigh’s post-Peterloo movie has its own epic qualities. His use of careful wide-screen framing imbues this latest account of a dysfunctional family with a measure of tragic gravitas, although it is essentially the story of one cosmically unhappy person, Pansy, introduced more or less as she goes about her day.

If dinner with Pansy is a nonstop enraged monologue, a morning in her company is a mad adventure wherein she gratuitously insults the saleswoman (and two customers) in a furniture showroom, gets involved in a slanging insult fest in the parking lot, and causes an instant commotion on a supermarket checkout line.

Initially funny in an outrageous, Marx Brothers sort of way, Pansy’s behavior is less so with regard to the medical professionals whose help she so obviously needs. Pansy rudely disrupts a physical exam—referring to the young doctor as “a mouse with glasses squeaking at me”—and terminates a trip to the dentist, screaming that she is being subjected to “torture” and that the treatment is “unacceptable.”

The specifics of Pansy’s evident mental illness are never made explicit—the hard truth is simply that it exists. Pansy’s long-suffering husband Curtley (David Webber), a self-employed plumber, and her reclusive son Moses (Tuwaine Barrett), headset firmly clamped over his ears, are emotionally numb, as noncommunicative as she is voluble. Pansy’s younger sister Chantelle and her family provide a contrast. Chantelle is the single mother of two playful, loving daughters, both in their 20s. Unlike Pansy’s sterile home, her apartment is alive with color, textures, and flowering plants.

As befits a movie that’s much concerned with parents and children, Hard Truths centers on Mother’s Day. Chantelle manages to persuade Pansy to accompany her to lay flowers on their mother’s grave, an act that inevitably triggers Pansy’s recitation of her fears and grievances. “Why can’t you enjoy life?” the exasperated Chantelle exclaims, causing her sister to shout back: “I don’t know!” Therein lies the crux. The scene is a prelude to a supremely painful family dinner chez Chantelle in which Pansy, whose phobias evidently include elevators, trudges upstairs, refuses to eat, and suffers a sort of breakdown, while her husband and son, who are used to her hyper-scolding outbursts, are paralyzed onlookers.

Naked, Leigh’s bleakest film before Hard Truths, unfolds in a nocturnal London as hellish as William Blake’s, but here, as in a number of Leigh’s other movies, the metropolis is sunny, even modestly bucolic. (The title of Life Is Sweet, a film that also centered on a struggling family, was not entirely ironic.) Like many of Leigh’s earlier works, Hard Truths is scored with wistful background music that, detached from the drama, transforms his characters and their quotidian lives into objects of contemplation. The Japanese master Yasujirō Ozu, a filmmaker Leigh is known to admire, does something similar in his family dramas.

Like Ozu, Leigh has recurring types and tropes. Hard Truths offers a number of these: obese, depressed children, antithetical sisters, revelatory cemetery scenes, and workplace mishaps. The latter served to bring the couples in Life Is Sweet and 2002’s more tumultuous All or Nothing closer together. Not so here. Moments before Hard Truth ends, Moses experiences a small miracle of human communication, amplified for occurring beneath the statue of Eros in Piccadilly Circus. But the movie’s last shots belong to unhappy Curtley and stricken Pansy, shown in separate close-ups.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The hardest truth of all would be no promise of reconciliation or emotional catharsis for these two people. Still, that Curtley can be seen to feel, and Pansy perhaps to reflect, leaves open the possibility that the truths of their lives might yet be hard-won.

More from The Nation

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past

The Pakistani qawwali icon sang words written centuries ago and died decades ago. He’s got a new album out.

The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish

Sure, it’s a dog whistle for “retvrn” types and the results are tacky—but that’s not the worst part.

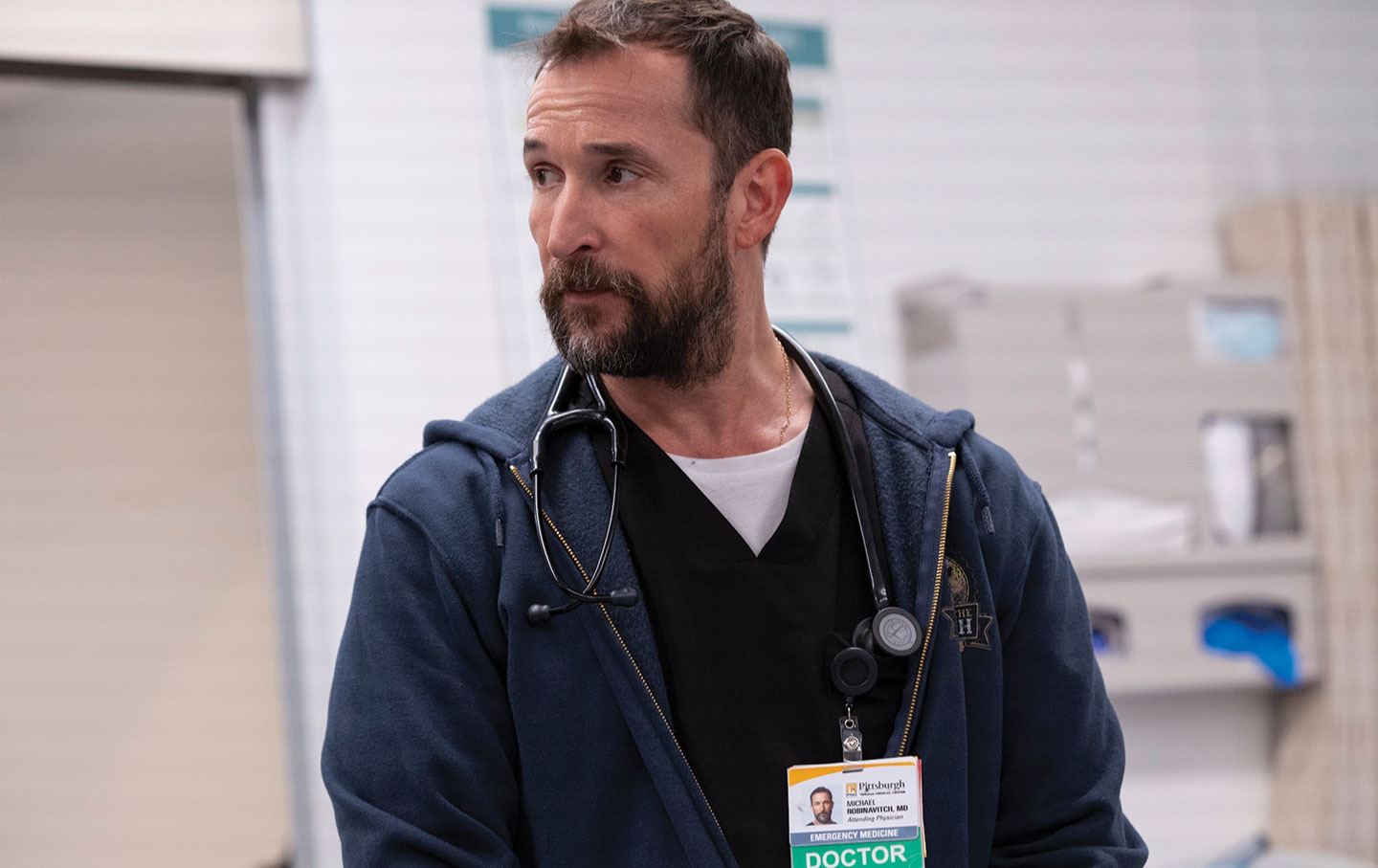

“The Pitt” and the Rise of a New Era of Hospital Dramas “The Pitt” and the Rise of a New Era of Hospital Dramas

In a frenzied medical drama, the limits and problems of the healthcare system became the basis of the show’s plot.

Henri Bergson’s States of Change Henri Bergson’s States of Change

Why did one of the early 20th century’s most famous philosophers go out of fashion?

The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker

Walker’s new installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art offers us visions from both the past and future.

A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation

Khawla Ibraheem’s play Knock on the Roof examines how the Israeli military terrorizes Palestinians in their most intimate and private spaces: their homes.