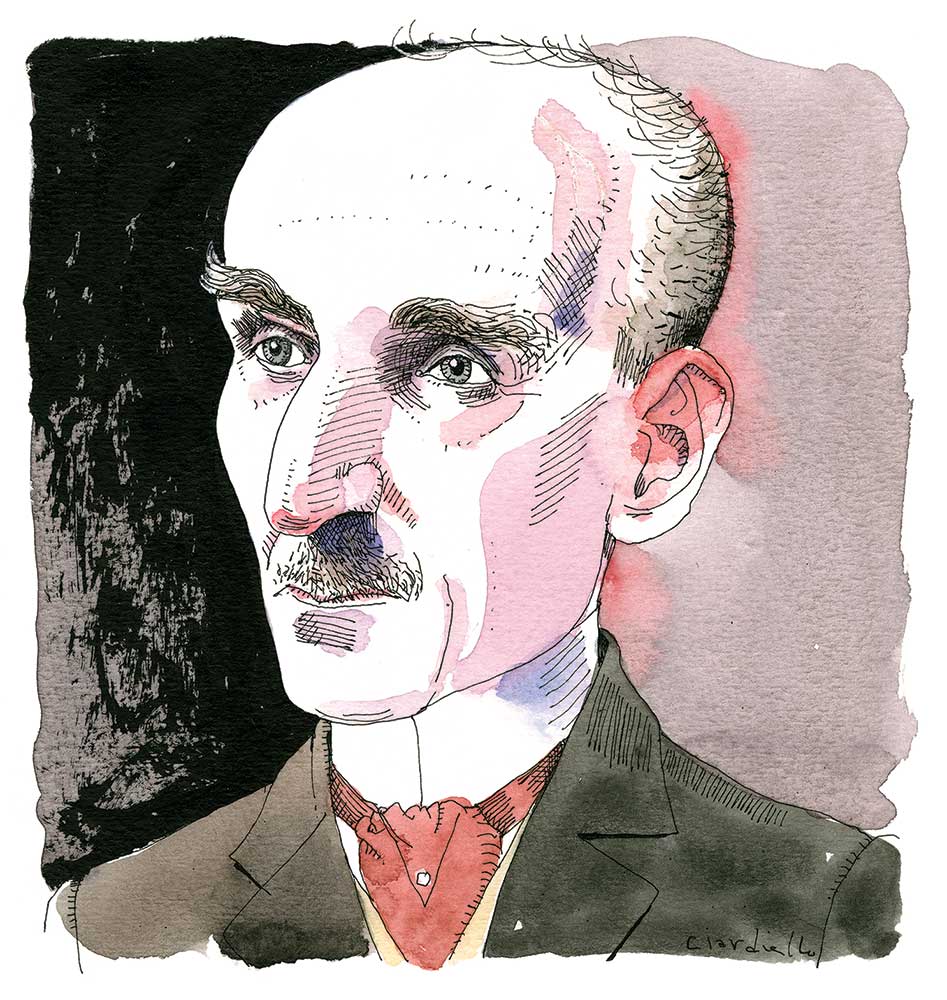

All Is Unfinished

Henri Bergson’s philosophy for our times.

Henri Bergson’s States of Change

Why did one of the early 20th century’s most famous philosophers go out of fashion?

Fama is a fickle deity. at the turn of the 20th century, Henri Bergson was one of the most famous people in the world, and certainly the most famous philosopher. Enormous crowds attended his lectures at the Collège de France in Paris—there are photographs of people thronging the street outside the college, scaling ladders and even standing on windowsills to try to catch a scrap of la leçon du maître. When he visited New York in 1913 to speak at Columbia University, so many turned out to hear him that Broadway experienced its first traffic jam.

Books in review

Herald of a Restless World: How Henri Bergson Brought Philosophy to the People

Buy this bookThis is hard for us to understand today, since Bergson is forgotten by all save a few specialists and enthusiasts. But thanks to Emily Herring’s fascinating and lively biography, Herald of a Restless World—the first in English, according to the publisher’s blurb—we are reminded just how much Bergson’s philosophy, although as hard to pin down as the poetry of Mallarmé and as shimmeringly elusive as an impressionist painting, has to say to us in our afflicted age. On the one hand, today the old Newtonian certainties that science used to lay claim to are crumbling, or indeed have crumbled; and on the other, bewilderingly swift advances in technology threaten not only our jobs but, as it often seems, our very souls. Bergson in his day was widely misrepresented as being anti-science, but he did have many questions, some of them awkward, to put to the scientists, and to science itself, with its claims to thoroughgoing rigor and unchallengeable verity.

Henri Bergson was born in Paris in 1859 to a Jewish family with Polish roots—the name was originally Bereksohn. His father was a composer and pianist; his mother, Katherine Levison, was an Englishwoman and the daughter of a doctor. Consequently, from his earliest years Henri was fluent in French and English. He first attended Jewish schools, but he abandoned religion in his teenage years.

Although his parents had moved to London, Bergson entered the highly regarded Lycée Condorcet in Paris and was, as Herring writes, “raised by institutions more so than by his parents. Like the organisms in Darwin’s theory [of evolution], the child Henri had to adapt and build resilience to survive.” This institutional upbringing may account, at least to an extent, for the adult Bergson’s tentativeness in general and his desire for privacy in particular. Bergson was adept at getting to know the right people and saying the right things to them. But he was also a shy, if astute, networker.

During his school years, Bergson proved to be a brilliant student, one who, according to his own claim, hardly had to study at all: “I only needed to follow a demonstration on the blackboard once to master it completely; I never had to memorise my lessons at home.” The truth of these assertions was shown when, as a boy, he came up with a solution to a problem in geometry set by no less an intellect than Pascal, a problem that had defeated Pascal’s great contemporary, the mathematician Pierre de Fermat. As Herring writes, “In his mind’s eye, [Bergson] could ‘see’ the relationships between the properties of geometric figures as clearly as most people could see objects in space.”

For Bergson, then, one of the chief properties of reality is its haecceity, its graspable thereness; another, perhaps more significant property is that the world and everything in it are in a constant state of change. What Bergson found unsatisfactory in science, both ancient and modern, was its tendency to “seek the reality of things above time, beyond what moves and changes.” Rather than seeking out a Platonic sphere of ideal forms and eternal verities, Bergson advocated for a philosophy that was set firmly on the common ground where humans live and have their being—even if that ground was constantly shifting.

In his most successful and famous book, Creative Evolution, Bergson wrote: “For a conscious being, to exist is to change, to change is to mature, to mature is to go on endlessly creating oneself.” This grand vision of change was a doctrine that perfectly chimed with the spirit of his age, an age in which the stability of the 19th century was disintegrating under the pressure of new advances in physics and biology and new movements in society and the arts. That this world of novel and creative disorderliness was heading toward the catastrophe of the Great War, not even a mind as keenly attuned to the music of time as Bergson’s could foresee.

In 1878, Bergson left the Lycée Condorcet and won entry to the École Normale Supérieure, the most exclusive university in France. “Of all the universities in the world,” Herring writes, “none has ever boasted a higher concentration of Nobel laureates per capita as the École.” In time, Bergson’s name would be added to that roll of honor.

It was at the École Normale Supér- ieure that Bergson befriended and became amiable rivals with Jean Juarès, the socialist thinker and activist who would go on to cofound the influential socialist newspaper L’Humanité and eventually one of France’s most prominent socialists. Indeed, in 1913, the year in which Bergson caused that traffic jam on Broadway, Juarès addressed a crowd of 150,000 protesters in Paris opposed to the coming war.

At the École, the two young men were the unquestionable stars: They knew it, and so did everybody else. In their third and final year, they sat for the agrégation, the exam that was (and remains, as Herring notes) “a necessary stepping stone for anyone aspiring to an academic career” in France. On the day of the oral section of the examination, which was open to the public, Juarès won by popular acclaim, but in the actual vote he lost out to Bergson, “and their rivalry remained intact.” It is a fascinating question as to how their relationship would have further developed—would Juarès have had a decisive influence on Bergson’s views of the world, of politics and society? But what might have followed is impossible to know: In the years after the École, Juarès became a founder of France’s Socialist Party and a vocal opponent of the militarism that erupted at the start of World War I, before he was assassinated in 1914 by a French nationalist.

At the École Normale Supérieure, Bergson became a firm adherent of Herbert Spencer. Herring, who has a genius for condensing complex philosophical and scientific postulates into digestible bites, explains that Spencer sought “to apply the rigor of science to the study of all levels of reality, from the atoms of physics to the bodies of organisms and the rational choices of moral beings.” Enthralled by Darwin’s theories of the natural world, Spencer attempted to apply them to society as well, coining the phrase “survival of the fittest.” But what appealed to Bergson in Spencer’s thought was his materialism and his desire to counter the woolier idealism of Immanuel Kant.

After Bergson graduated from the École, however, he would come to reject Spencer’s materialism tout court and embrace two concepts that would replace it: durée and élan vital. The first of these was inspired, in part, by music. For Bergson, the son of a composer, listening to music was, as Herring notes, “one of the human experiences that best illuminated real time.” It was, in other words, durée—to quote Bergson himself, “the continuous progression of the past, gnawing into the future and swelling up as it advances” so that “our personality constantly sprouts, grows, and matures. Each of its moments is something new added onto what came before.” Or as Herring puts it in an apt and homely fashion: “Our personality is like a snowball rolling down a hill, accumulating experience as it grows. Time that passes is not lost but rather it is gained. We carry our whole history with us as we advance.”

For Bergson, the principle of élan vital also represented an effort to integrate time into his thinking: It offered an account of natural evolution that is less mechanical, less determined, than what we find in Darwin and in Spencer. Élan vital represented the “continuity of change,” the “preservation of the past in the present,” the way that “life, like conscious activity, is invention, is unceasing creation.”

From both of these ideas, we can easily see why some philosophers of a more analytical bent never passed up an opportunity to dismiss Bergson and his work. Herring quotes Bertrand Russell’s insistence that “ordinary language is totally unsuited for expressing what physics really asserts, since the words of everyday language are not sufficiently abstract.” Bergson, for his part, prized the ambiguousness of language since it allows us to generalize, and generalization is the essence of human discourse. The word “tree” is both that leafy object standing before us and its own ideal, the Tree of all trees. Or as Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus has it in Ulysses, “Horseness is the whatness of allhorse.”

The object—the tree, the horse, the idea—may be approached in two ways, by analysis or intuition, the latter, in a special form, being another of Bergson’s key ideas. As Herring explains: “Analysis remains external to its object, apprehending it through symbols and ready-made concepts. Intuition, on the other hand, ‘neither depends on a point of view nor relies on any symbol’”; in Bergson’s beautiful formulation, intuition instead “follows the undulations of the real.”

This and other assertions were surely part of the good news that brought those eager listeners thronging into the lecture halls of the Collège de France and Columbia University.

Bergson’s interest in the question of time was also reflective of his times. One of the most consequential encounters in his career took place in Paris in 1922, under the auspices of the Société Française de Philosophie, when he joined Albert Einstein in a debate on, among other matters, the nature of time. Perhaps “joined” is not the word, for it was a prickly and controversial contest between two of the world’s most eminent figures in philosophy and physics. In fact, the debate was to an extent accidental, as Bergson was not scheduled to take part in it but was spotted in the audience and invited to speak.

The philosopher Xavier Léon had launched the proceedings by pointing out that one of the main aims of the Société was to open channels of communication between philosophers and scientists. Einstein, however, was not at ease. There was the old rivalry between France and Germany to be coped with; antisemitic passions still lingered after the Dreyfus affair; and Einstein’s command of the French language was less than secure.

But at the heart of the debate between the two men was a pressing question: Was Einstein’s theory of relativity a description of reality as it actually is, or just another hypothesis—although a hypothesis of genius—that fitted the facts more neatly and in a more aesthetically pleasing fashion than any theory that had gone before, including Newton’s mechanistic account of the world and how it works. Einstein, of course, insisted the former. Bergson did not entirely disagree, but he also viewed Einstein’s theory as abounding with theoretical possibilities: “Once the theory of Relativity has been accepted as a physical theory,” he asserted, “all is not finished.”

The Nobel laureate’s response was as terse as it was dismissive: “The time of the philosopher does not exist.” Here again we see, as with Russell, the suggestion, and more than the suggestion, that Bergson was hopelessly misty in his thinking, which, in fairness, is not something Bergson denied. As he wrote in Creative Evolution, there persists around our (in this context, read “his”) “conceptual and logical thought, a vague nebulosity, made of the very substance out of which has been formed the luminous nucleus that we call the intellect.”

And then, as suddenly as it had dawned, Bergson’s day entered its dusk. During the First World War, he made some injudicious public statements and a number of controversial speeches for which he was roundly attacked. In an era of barbarous war and upheaval, the abstractions of Bergson also fell out of favor. There was, after all, the lingering shadow of Einstein’s retort on all of his thinking and the continuing accusations in some quarters that his work was trivial and inconsequential.

There were other material reasons for the waning of Bergson’s influence. In the mid-1920s, his health began to fail and he withdrew from public life. As he wrote to a friend: “I am extremely tired. For twelve or fifteen years I have not taken a day, not even a half day of proper rest.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Among many of his detractors, the response to his departure was “Good riddance.” In 1929, the Marxist philosopher Georges Politzer published a pamphlet in which he wrote, with a level of cruelty remarkable even in a Marxist, “Mr Bergson is as yet still dying, but Bergsonism is in fact dead.”

Yet Bergson’s eclipse has been a misfortune not only for the philosopher but for the world. A thinker of his subtlety, sensitivity, and imaginative reach is exactly what we need now. As Herring writes: “With the current climate crisis”—and, we might add, the numerous other perils facing the world—“the survival of our species depends on our ability to come up with creative solutions to unprecedented challenges. Who better to turn to than the critical thinker of radical change and creativity?”

Herring takes the title of her splendid book, and its epigraph, from another once widely famous and now largely forgotten figure, the journalist Walter Lippmann, who wisely wrote that “Bergson is not so much a prophet as a herald in whom the unrest of modern times has found a voice.” It is a voice to which we would do well to lend again our collective ear.

More from The Nation

“The Pitt” and the Rise of a New Era of Hospital Dramas “The Pitt” and the Rise of a New Era of Hospital Dramas

In a frenzied medical drama, the limits and problems of the healthcare system became the basis of the show’s plot.

The Uncomfortable Genius of Mike Leigh The Uncomfortable Genius of Mike Leigh

In “Hard Truths,” Leigh reminds us that a family dinner can tell the story of a whole society.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past

The Pakistani qawwali icon sang words written centuries ago and died decades ago. He’s got a new album out.

The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish The Real Problem With Trump’s Cheesy Neoclassical Building Fetish

Sure, it’s a dog whistle for “retvrn” types and the results are tacky—but that’s not the worst part.

The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker

Walker’s new installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art offers us visions from both the past and future.

A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation

Khawla Ibraheem’s play Knock on the Roof examines how the Israeli military terrorizes Palestinians in their most intimate and private spaces: their homes.