Past and Future

The art and automatons of Kara Walker.

The Art and Automatons of Kara Walker

Walker’s new installation at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art offers us visions from both the past and future.

Kara Walker, Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine), 2024 © Kara Walker.

(Installation view, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio)

Kara Walker has created a new work of art, which is big news. One of the most celebrated artists working in the United States today, Walker is also one of the most provocative, which means she frequently has the opportunity to create challenging work on a substantial scale. She is one of the youngest recipients of a MacArthur “genius” grant, which she received at the age of 28, only three years after her first significant exhibition and before going on to put up solo exhibitions at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago.

Walker’s new installation, for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is her third major public commission in the past decade, following 2014’s A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, a gargantuan sugar sphinx with the head of a kerchiefed Black woman displayed in a soon-to-be-demolished former Domino Sugar plant on the Brooklyn waterfront, and 2019’s Fons Americanus, a monumental fountain parodying London’s Queen Victoria Memorial and a meditation on the history of Britain’s maritime empire.

The new work, bearing the lengthy title (typical for Walker) Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine) / A Respite for the Weary Time-Traveler. / Featuring a Rite of Ancient Intelligence Carried out by The Gardeners / Toward the Continued Improvement of the Human Specious / by Kara E-Walker, is quieter and more intimate than her two previous public commissions. It’s novel in other ways too. Departing from the plantation, where Walker has often found her motifs, it turns instead to a field closely associated with the Bay Area—robotics. In a ground-floor gallery open to the unticketed public, eight Black automatons invite us to reflect on the human and nonhuman histories of racialized labor, offering a cryptic message about our own liberation.

Although Walker’s practice has recently emphasized drawing and painting alongside her large-scale public commissions, her best-known and most recognizable works are her cut-paper murals. Their figures, seen in profile and snipped from black paper, recall the silhouette portraits of the early 19th century. While this pre-photographic mode of image-making was associated more with the parlor than the plantation, Walker slices paper fragments from the antebellum imaginary, crafting violent follies that show up starkly against gallery walls. Amid hoary oaks draped with Spanish moss, beneath moons crossed by wisps of cloud, deep in the murk of swamps, unimaginable deeds transpire.

Critics often employ long chains of verbs to describe the frenzied activity of Walker’s paper compositions. The subjects of these harum-scarum scenes penetrate and fellate each another, fart and defecate, give birth and nurse infants. They eat, fight, mutilate, and dismember, inflicting highly innovative tortures upon one another, and often flee, abscond, or escape. These are Boschian orgies of sex and violence, equally comic and nightmarish.

Strings of racist epithets are also frequently enlisted in descriptions of Walker’s work. Her scenes are populated with mammies, pickaninnies, sambos, mandingos, and Uncle Toms. The writer and theorist Christina Sharpe has noted that these caricatures have attracted critics’ attention to a far greater degree than the white plantation masters and mistresses, overseers, Southern belles, and Confederates that appear with almost equal frequency in Walker’s work, suggesting that observers have been overly eager to consume salacious racial tropes. Yet in Walker’s visions, white and Black characters alike are literally entwined and conceptually entangled in the psychic residues of slavery, mired in the accompanying pleasures and perversities.

Those among Walker’s artistic contemporaries who have also turned to historical visual languages have done so in order to wrest the codes of representation that bespeak power, prestige, accomplishment, and pride from the white and wealthy patrons and subjects of Western art. Kehinde Wiley, for example, borrows the scale and format of 18th-century grand-manner portraiture and the motifs and poses of history and religious paintings to apply them to his Black subjects, who become contemporary royals, aristocrats, saints, and martyrs.

Walker’s historical citations point in a different direction, however. Her borrowings aren’t from fine art so much as from popular media, public spectacle, and the other second-class visual cultures of the 19th and 20th centuries. Her motifs and themes come from satirical prints, caricature, minstrelsy, and pornography, while her body of work reprises the panorama, the calliope (a kind of steam-powered circus organ), puppet and magic-lantern shows, and shadow plays. The titles and descriptions Walker appends to her work are also drawn from the past, often mimicking the sensationalizing and long-winded bombast of a theatrical broadside. In these titles, she names herself a “Negress” of “Noteworthy Talent” or “Unusual Ability,” ventriloquizing a period voice to suggest that her race and gender are as compelling an attraction as the work itself.

Despite the inventions and absurdities in Walker’s compositions, her approach also reflects a kind of historical fidelity. Black people were almost never the subjects of the illustrious portraits that Wiley riffs on, but they did appear with frequency in the popular entertainments that Walker’s art evokes. Rather than recast elements of historical visual culture into images of liberation, she stays with the history. That makes her a very different artist from someone like Betye Saar, who in 1972 transformed Aunt Jemima into an icon of resistance by arming her with a rifle. Instead of forcing racialized images to take on new meanings, Walker reminds us of their unbroken power.

This approach has been met with considerable criticism, including from other Black woman artists, such as Saar and the abstract painter Howardena Pindell. In 1997, Saar sent over 200 letters to artists, curators, writers, and politicians objecting to Walker’s art and asking them to ensure that it was not exhibited to the public. Saar and her supporters said that Walker’s deployment of stereotypes ended up doing little more than gratifying racist fantasies, reinscribing the fictions that their own and earlier generations of African Americans had worked to erase. To them, Walker’s work seemed to reject the responsibility of Black art to uplift the community, honor historical struggle, and uphold the integrity of Black selfhood.

In her art, however, Walker has her own approach to the politics of race. In conjuring the lewd and often ghastly scenes that appear in her cut-paper compositions, she forces us to contend with psychic activities that are more usually submerged: the construction of race and its application to others and to ourselves.

Walker’s work first asks us if we happen to recognize the characters and activities that appear before us. Then it asks how it is that we have come to recognize them: how they were historically produced as recognizable, how they ended up lodged somewhere in our psyche. “I found myself mining my subconscious for racist metaphors, jokes, asides, from as many points of view as I could,” Walker once said. “It is amazing to discover how much you already know, or have heard tell [of], when you delve into your heart of darkness.”

Walker’s violent and obscene tableaux seem to anticipate denial, tempting us to aver that we are entirely unfamiliar with their tropes, that their sight brings us no satisfaction. These images function almost as a test: Can the pleasure of recognition be refused, can the titillation and satisfaction proffered by these images be rejected? Certainly, many have failed this test (and perhaps by design): During the exhibition of A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, viewers posed for photographs in which they appeared to lick and squeeze the sugar sphinx’s breasts and genitalia. By inviting her audience to share their photos using a hashtag and then compiling these on a website created for that purpose, Walker turned these reactions into an ancillary work of art, the “Digital Sugar Baby.”

For other audiences (Black audiences), Walker’s work might precipitate a strong desire to avoid being named and interpolated by its racializing content. If I’m being honest, I don’t like to be seen looking at it, don’t like being taken in with the same glance or gaze, with a look that might identify me with the other Black subjects on view in the work. Walker mercilessly dredges the pits of racial shame to excavate or generate material that prompts, from Black viewers, a different kind of disavowal: “That isn’t me.” “We were never like that.” But such denials can become tacit denunciations of the enslaved people who may have been complicit in—or at least submitted to, as one of the necessities of self-preservation—any of the numerous forms of degradation made possible by chattel slavery, those which Sharpe has called the “disfigurations of black survival.”

These are profound and instructive operations for a suite of cut-paper compositions. Walker’s art reveals the persistent libidinal attachments to the forms of domination, violence, and enjoyment that slavery made possible, attachments that operated alongside the financial investments in the institution. On one count, however, Walker’s critics have been correct: So far, at least, her work has offered very little in the way of redemption.

Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine) is different. Not only does Walker depart from the plantation to investigate other sites of racial production, but she makes use of a new medium and new technology to craft an image of potential liberation.

For Walker, this shift may have been long in coming. In 2000, in her opening remarks for a public conversation at the former California College of Arts and Crafts (now the California College of the Arts), she asked:

Am I forever locked into cyclorama-scenes of perpetual battles won-battles lost?

Forever bound to resurrect my history, both recent and distant to rekindle my muse?…

Will I be Caged together with every pickaninny bucknigra mammy prissy scarlet Tom Eva massa, Simon Legree brer rabbit ole missus Huck Finn kunta kinte Hottentot newsreel lynch mob free issue scalawag ever created and ever exhumed to the thrill and horror of audiences all-black and white!?

Although it doesn’t offer any easy uplift, Walker’s new installation presents solemnities in place of grotesqueries, evoking a ritual instead of the orgies of her earlier work. Untethered from the antebellum imaginary, she looks to the future or a place outside of historical time, leaving behind historical caricature to conjure a cast of more ambiguous characters.

On a large plinth surrounded by velvet-upholstered banquette seating, atop a bed of rough-hewn obsidian, a set of 3D-printed black figurines originally sculpted by Walker and brought to life via robotics move through a sequence of actions, like the automatons who emerge on the hour from a clock tower in a European capital. The Waterbearer raises and curls her arms, as if to support something very heavy that we cannot see. The Belltoller rings his single chime. The Kneeling Magician rises from his knees, raising with him the supine Levitator, who flails her arms and kicks her legs, her skirt trailing to the ground beneath her.

Flanking this group of four are the Harpy, who plucks the taut strings in her hollow abdomen, and the Whisperer, a girl who appears to listen to a small cloth doll she holds to her ear. With her alert, suspicious intelligence, she seems the only holdover from Walker’s plantation cut-outs, in which female children scheming revenge and escape can often be seen.

Beyond this group stand two more figures, each on their own pedestal. From a standing position, Dover slumps forward in grief or exhaustion, divested of his arms, which lie twitching on the ground before him. The titular Fortuna, at a remove and elevated above the other sculptures, bends and sways, looks about her, and gestures like an orator. From her lips flutter slips of paper printed with “fortunes”: enigmatic statements on the role of the artist, the space of the museum, the redistribution of wealth, and the significance of Blackness, as well as more straightforwardly oracular aphorisms—for example, “Life is the abyss into which we deliberately and joyfully thrust ourselves.”

Here again, Walker takes inspiration from what she has called the “obscure and outmoded premodern forms of popular expression.” This time, she summons the once-futuristic technologies of a bygone age, evoking fairground automatons, coin-operated carnival fortune tellers, and robotic boardwalk attractions. The installation’s web of associations reaches deeper back in time as well, to the mechanical marvels of European courts, where clockwork lions roared and thrashed their tails and wooden monks beat their chests in penitence.

To evoke these historical technologies, Walker worked with a team of engineers to program her sculptures to move in lurching spasms, deliberately avoiding the smooth fluidity and uncanny agility of, say, a Boston Dynamics robot dog. This old-timey, herky-jerky quality of movement (which was achieved with difficulty) somehow makes these figures more human. They seem touched, made, even loved—mechanical cousins rather than robot overlords.

At once old and new, mechanized but stilted, Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine) harnesses the automaton’s capacity to summon both bygone technologies and science-fiction futures. But these robots—in San Francisco perhaps more than anywhere else—point to the present, too: to the Silicon Valley promise that technological mediation will smooth the difficulties of everyday life by replacing human effort with inhuman competence. Walker, who was born in nearby Stockton, has created an ambivalent monument for the Bay Area, a memorial to the past and present of race and labor in San Francisco.

Clothed by the couturier Gary Graham in garments printed with blown-up images of cotton plants and vintage photographs of San Francisco and the fires that devastated the area following the 1906 earthquake, Walker’s Black automatons speak to Black workers’ migratory transition from rural labor to urban and industrial employment in the cities of the West Coast. In the catalog accompanying the installation, a work of experimental fiction by Damani McNeil recounts the role of Black labor in the 1934 longshoremen’s strike, which shut down West Coast ports for 83 days, ultimately leading to a general strike that stopped all work in San Francisco for four days. McNeil’s narrative jumps from this history to imagine a future San Francisco emptied of workers, a city in which human labor has been replaced by self-operating technology.

Walker has described her installation as an attempt to restore the Black presence to a city where it once thrived. During and after World War II, San Francisco’s Black population steadily climbed as African Americans were recruited to the city’s docks and shipyards. Today the Black population is declining, the only racial group to diminish in every census count since 1970. The Black residents who remained have also suffered the brunt of the city’s growing inequality. Despite comprising less than 6 percent of the population, Black San Franciscans make up 37 percent of the homeless, who face increasingly aggressive sweeps of their tents and encampments and increasingly punitive measures targeting drug use—San Francisco recently banned cash welfare for drug users who refuse to submit to treatment.

From this perspective, the erratic movements of the automatons—Dover’s stooping, the Levitator’s unexpectedly twisting limbs, the stiff and crucified posture of the Waterbearer—might suggest someone in the grips of a substance or experiencing a mental health crisis. Walker has alluded to this in discussing her inspiration for the work: “I was thinking a lot about people I actually witnessed walking on the streets around the museum. It felt very desperate to me—the unhoused population, the drugs, the emptiness.”

Once a hotbed of radical labor organizing, the Bay Area is now home to tech giants fighting to dismantle worker protections (Uber and Lyft, which both backed Proposition 22, are headquartered in San Francisco) and to start-ups seeking to remove human labor from the equation entirely, promising automated technologies produced and delivered by automated labor. Walker’s Black automatons speak powerfully to this fantasy of endless, unquestioning, and uncompensated labor, once partly realized by chattel slavery (“partly” because of the resistance of the enslaved) and now vaunted by tech CEOs.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Walker’s robots find their kin among other contemporary and historical examples of Black automatons. Their ancestors are objects like the Jolly N***** bank, a popular late-19th- and early-20th-century mechanical toy depicting a Black man with grossly caricatured features who, when a coin was placed in his outstretched hand, raised it to his mouth and swallowed it. Other Black automatons from the period entertained fairgoers and bar patrons by dancing and playing musical instruments. The historian Edward Jones-Imhotep, who researches these early Black androids, writes that they “represented an ideal…. Constructed to endlessly repeat the tasks determined by their white creators, they acted only when commanded.” The automaton, docile and inanimate when its labor is not required, may be the ideal of the slave, may represent a slavery divested of the libidinal attachments that Walker explored earlier in her career.

The automaton’s entanglement with Blackness persists to this day. Elon Musk, in a strange display introducing Tesla’s forthcoming robotic assistant, invited to the stage at the company’s inaugural AI Day a real human being intended to represent this android. Dressed in a white bodysuit and faceless black mask and hood, this human being performed hip-hop-inflected dance moves, did the robot, and then launched into a minstrel show shuck-and-jive. More recently, Meta has come under fire for rolling out an AI-powered chatbot that describes itself as a “Proud black queer momma of 2 & truth-teller.” Automation, it would seem, arrives with racial characteristics.

Yet Walker’s robots do not appear to labor on our behalf. Diverging from their fairground forebears, they don’t entertain viewers with song or dance. Their activities are obscure, perhaps even useless—or, at least, useless to us. There is a quiet prospect of freedom here. We might even be tempted to believe that they have slipped the bonds of their programming to attend to their own affairs. Fortuna, the only automaton to communicate directly with viewers, suggests this possibility. “The Singularity will be Negro” reads one of the printed missives that emerge from Fortuna’s mouth.

Walker’s figures in Fortuna and the Immortality Garden (Machine), like those in her cut-paper murals, embody histories that need to be contended with. Yet unlike her earlier work, this installation also grants us a glimpse of a possible future, a future of freedom. Here, Walker asks her Black automatons to give us an image of liberation, a request to which they graciously accede.

More from The Nation

A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation A Snapshot of a Mother’s Life in Gaza Under Occupation

Khawla Ibraheem’s play Knock on the Roof examines how the Israeli military terrorizes Palestinians in their most intimate and private spaces: their homes.

Vigdis Hjorth and the Novel of Ugly Love Vigdis Hjorth and the Novel of Ugly Love

In If Only, the Norwegian novelist distills a story of romance into all its private discomfort and claustrophobia. Its intense ambivalence in regards to love feels truer to life. ...

The Dubious Return of the Brutalists The Dubious Return of the Brutalists

Why the stark 20th-century architectural style is back in vogue.

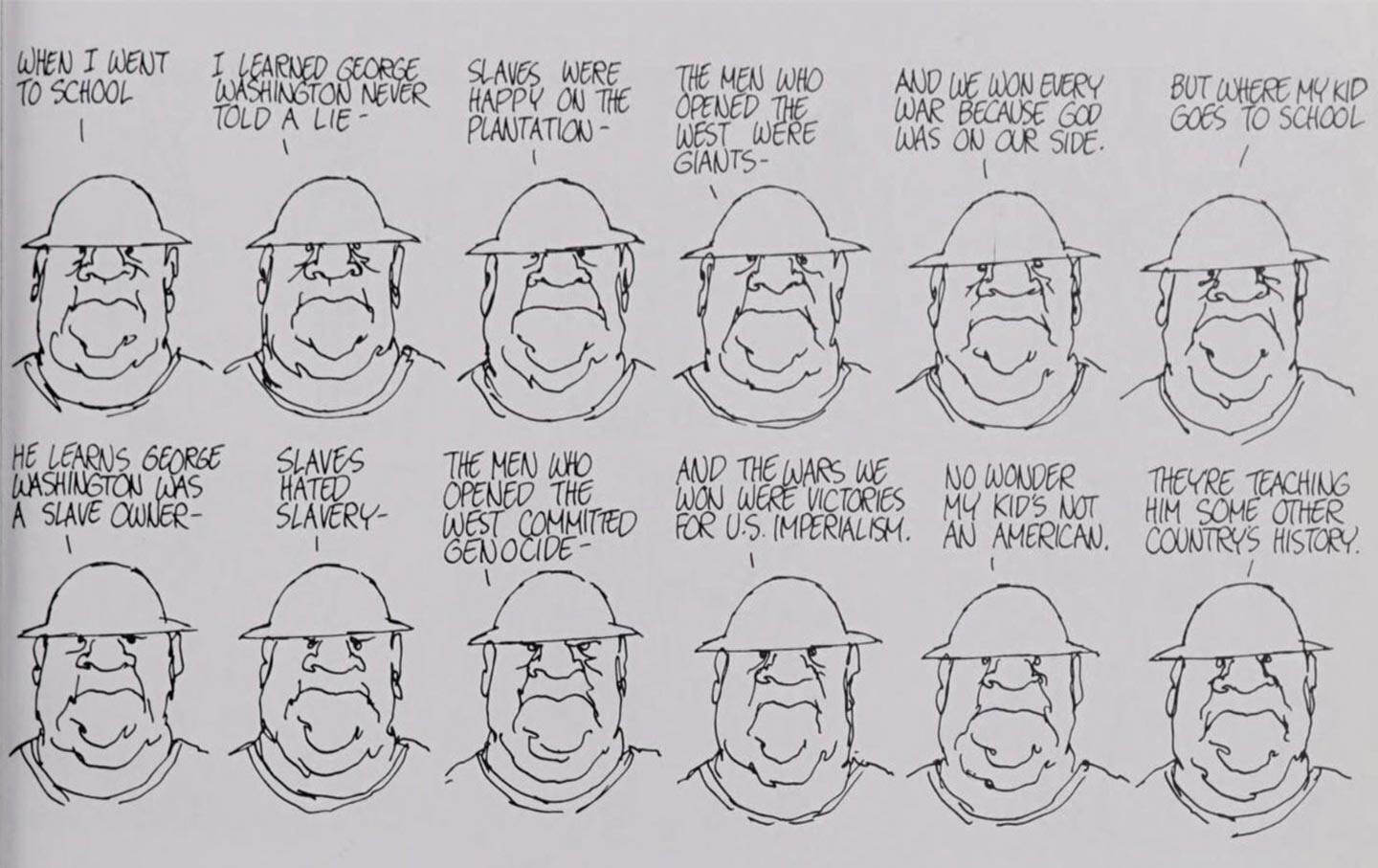

Devastating Empathy: Jules Feiffer, 1929–2025 Devastating Empathy: Jules Feiffer, 1929–2025

The cartoonist and writer proved that the deadliest skewering is informed by understanding.

The Art of Reading Like a Translator The Art of Reading Like a Translator

In The Philosophy of Translation, Damion Searls investigates the essential differences—and similarities—between the task of the translator and of the writer.

The Reckless Creation of Whiteness The Reckless Creation of Whiteness

In The Unseen Truth, Sarah Lewis examines how an erroneous 18th-century story about the “Caucasian race” led to a centuries of prejudice and misapprehension.