Daniella Weiss, the 79-year-old leader of the far-right settler organization Nachala, stepped out of her white Mitsubishi SUV and into the parking lot of the Sderot train station, a mere three kilometers from the Gaza Strip. It was December 26, the second night of Hanukkah, and for weeks Nachala had been aggressively promoting a celebratory “procession to Gaza” and candle-lighting ceremony in a closed military zone by the border. The event was to be the next step in Nachala’s escalating campaign to rebuild Jewish settlements in Gaza. If they could not yet enter the Strip, they would at least try to get as close as possible.

A group of teenage girls in ankle-length skirts rushed to take selfies with Weiss, who had been sanctioned by the Canadian government in June for perpetrating extremist violence against Palestinians in the occupied West Bank. Nearby, a scrum of yeshiva students from Sderot jumped and chanted, “Am Yisrael Chai”—an old slogan that means “The people of Israel live,” which has become a nationalist mantra. In the back corner of the parking lot, two shipping containers (what the settlers call caravans) emblazoned with the words “Gaza Is Ours Forever!” sat atop heavy flat-bed trucks waiting, it seemed, for the order to drive into the devastated territory. In the distance, occasional explosions in Gaza illuminated the horizon with a hellish light, the sound rattling the windows in an adjacent strip mall.

“We are going to take this procession to the area of the Black Arrow, to a hill that overlooks Gaza,” Weiss told me when I asked about Nachala’s plan for the night. (The Black Arrow is a memorial to Israeli paratroopers, administered by the Jewish National Fund, less than a kilometer from the cement and razor-wire barrier that separates Gaza from Israel.) “Hopefully, the police will let us get there,” she added, grinning. “We always find a way.”

Weiss’s fundamentalist fervor belies her years. One of the last of the founding generation of settler leaders still alive, she is a former general secretary of Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful), the messianic religious-nationalist movement that erupted in the early 1970s and launched the settlement enterprise in the occupied West Bank. As they entered middle age, many of Weiss’s counterparts traded the militant life for bourgeois comfort under the terra-cotta roofs of suburban settlements or put their time of terrorism and sabotage behind them for careers in the media or politics. Not Weiss.

Aside from a stint as mayor of Kedumim, an ultra-hard-line settlement near the Palestinian city of Nablus, Weiss remained on the hilltops of the occupied West Bank, exhorting young Jewish Israelis to take over the land. In 2005, she founded Nachala with another leader of Gush Emunim’s ultra-extremist flank, Moshe Levinger of the notorious Kiryat Arba settlement near Hebron, with the aim of keeping the antiestablishment flame of the settler movement burning. In the years since, she has become something of a guru to the radical hilltop youth settlers, guiding them in the construction of illegal outposts and in the art of resistance, both civil and uncivil, to any attempts by Israeli authorities to control them.

Almost immediately after the Hamas attack on October 7, 2023, Weiss and the rest of the right-wing settler movement set their sights on Gaza. Against the backdrop of Israel’s massive bombardment and the ethnic cleansing of the territory’s north, they ramped up their efforts to reestablish Jewish settlements there, broadcasting their intentions loudly and bluntly—and with the knowledge that they could count on significant support within the governing coalition. This past December, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, who leads the Religious Zionism party, declared (not for the first time) on Israeli public radio, “We must occupy Gaza, maintain a military presence there, and establish settlements.” Many in Smotrich’s camp wanted to prolong the war, reasoning that the longer Israel continued to brutalize Gaza, the greater the likelihood that settlers would succeed in installing an outpost—the germ of a settlement—in the Strip.

The announcement of a ceasefire agreement briefly slowed the Gaza resettlement movement’s momentum, but it has not stalled it. The ceasefire is fragile, dangerously so: There is no guarantee that it will last beyond the initial six-week phase, which involves only a partial Israeli withdrawal from the territory. Indeed, within days of its announcement, reports began to leak out that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, to keep his hard-right government together, has conceded to Smotrich’s demand that Israel restart the war after the first phase ends and gradually assert full Israeli control over the Gaza Strip.

Amid this initial uncertainty, the settler movement continued to press its eliminationist vision of recolonizing Gaza. Then, last week, Donald Trump announced his surprise plan to ethnically cleanse the entire Strip of Palestinians and take over the territory. Israel’s far right—and, indeed, much of the center—has greeted the proposal with unmasked enthusiasm. Weiss was euphoric. “Assuming that Trump’s announcement regarding the transfer of Gazans to the nations of the world is translated into action,” she said in a Feb. 5 statement, “we must hasten to establish settlements in every part of the Gaza Strip.”

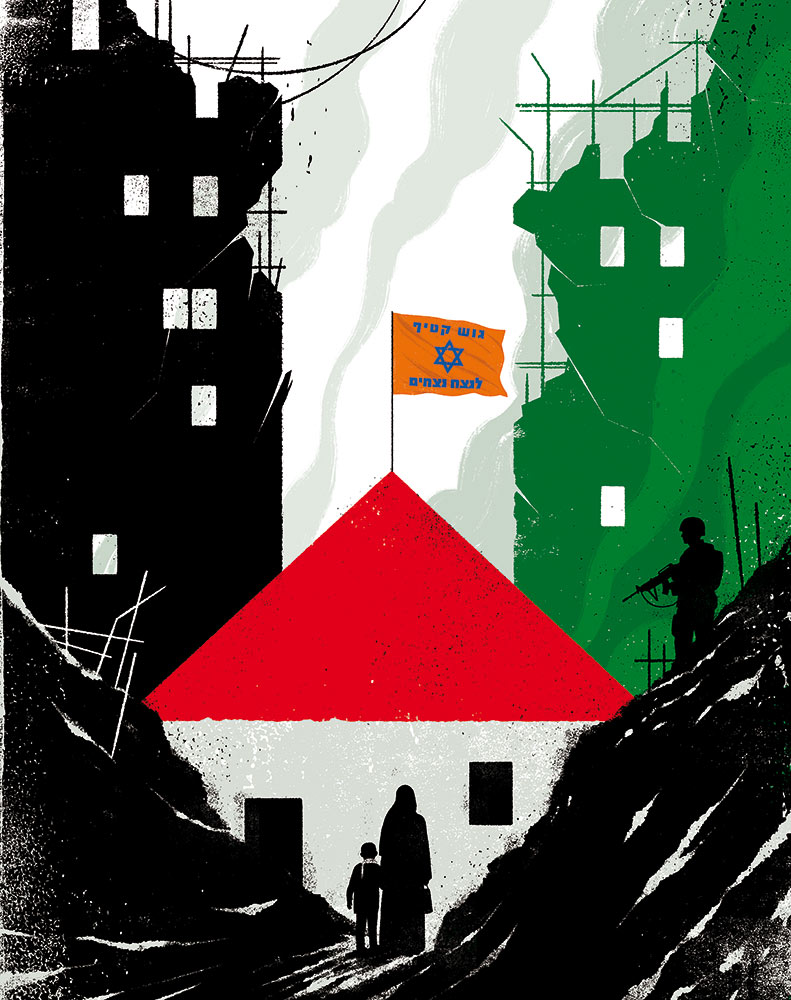

Israel’s religious-Zionist settlement movement burst onto the scene following the country’s victory the 1967 War. It was during that conflict that Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza, the Golan Heights, and the Sinai Peninsula—and it was just a few short years later, in the early 1970s, that successive Israeli governments began enabling the construction of settlements across the newly occupied territories. By the 2000s, the Gaza Strip had become home to nearly 9,000 Israeli settlers living in a total of 21 settlements. Seventeen were in an area that Israelis called Gush Katif, on Gaza’s southern coast, which effectively blocked Palestinians in the cities of Khan Younis and Rafah from access to the Mediterranean Sea.

Many of the settlers who made their way to Gaza came from the more ideologically extreme factions of the religious-Zionist movement. Devout believers in the messianic vision of a Jewish physical presence in every inch of the biblical land of Israel, they exacted an enormous cost—above all from the almost 2 million Palestinians forced to live under military occupation, but also from the thousands of Israeli soldiers required to secure the settlements deep in the Gaza Strip.

In 2005, under Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, Israel carried out what Israelis call “the disengagement”—the unilateral withdrawal of all Jewish settlers from the entirety of the Gaza Strip. The decision was a striking about-face for Sharon, who for much of his life had been an ultra-hawk and had done a great deal to boost the settlement project himself. In remarks to the international public, Sharon stressed that he hoped the disengagement would show that Israel was serious about making the kind of territorial compromises necessary to reach an eventual peace agreement with the Palestinians. To the Israeli public, Sharon argued that these particular settlements made little strategic sense; Gaza was not home to any ancient sites of serious religious significance, and defending the settlements demanded too much human sacrifice. In private, however, Sharon and his advisers had a different goal: to put the possible creation of a Palestinian state on hold by delinking the fates of the West Bank and Gaza. “The significance of the disengagement plan is the freezing of the peace process,” Dov Weisglass, a Sharon adviser, famously said. “The disengagement is actually formaldehyde.”

Still, for the members of Israel’s religious-nationalist right, any territorial withdrawal was unacceptable. Since 2005, they have viewed the disengagement as an intolerable wound—a “historical injustice” that needs to be rectified, as they often put it.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →With the start of the ground invasion in October 2023, Israel’s extreme religious Zionists saw an opportunity. Right-wing soldiers began to upload videos of themselves vowing to return to Gush Katif and resettle Gaza. Amid the rubble, they planted the orange flag that had become the emblem of the anti-disengagement movement, unfurled banners proclaiming the future sites of new settlements, and nailed mezuzahs to the doorframes of ruined Palestinian homes. While much of Israel spent the months after October 7 in mourning, the leadership of the settler movement entered a state of near-ecstatic anticipation that has only deepened with time. “From my perspective,” Orit Strook, a government minister from the Religious Zionism party, remarked in the summer, “this has been a period of miracles.”

For its part, Nachala began convening events intended to cultivate support for the reoccupation and resettlement of Gaza. In November 2023, just weeks after October 7, it held a convention devoted to this aim in the southern city of Ashdod. A few months later, in January 2024, Weiss and her extremist partners organized the Conference for Israel’s Victory in Jerusalem, attended by several thousand people, including 11 cabinet ministers and 15 members of the governing coalition, where speakers hailed the efforts to rebuild settlements in Gaza and called for the expulsion of Palestinians living there. On Israel’s Independence Day, in May, Nachala organized a rally in Sderot, during which National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir reiterated the movement’s demand for the “voluntary departure” of Gaza’s inhabitants—a gross euphemism for ethnic cleansing—in front of a cheering crowd of thousands. And in October, Nachala put on a “festive” gathering for the holiday of Sukkot in a closed military zone near the border, where far-right activists set up booths and convened workshops on how to prepare for Gaza’s resettlement.

When the group gathered in December for the Hanukkah celebration in the Sderot parking lot, the crowd was considerably smaller, but the atmosphere was no less jubilant. “Would you like to join our settlement core?” asked a woman wearing an orange head wrap; a charm depicting the rebuilt Third Temple hung on a gold chain around her neck. She was selling T-shirts, towels, car flags, and onesies for infants printed with the words “Gaza Is Part of the Land of Israel!” to raise money for the efforts of her “nucleus,” or settlement group. Of the six such “nuclei” organized by Nachala to settle different parts of the Strip, each consisting of roughly 100 families, hers—the nucleus for north Gaza—was “the best,” she said, “because it is the most realistic.”

This is the case, she explained, because the Israeli army had already “emptied” most of northern Gaza. As for the Palestinians who remained, she added, “they are obviously not innocent,” so they would be dealt with accordingly—in other words, expelled or killed. A resident of Ashkelon, a city 19 kilometers north of Gaza, the woman was so certain that the resettlement efforts would succeed that she had declined to renew her lease for the coming year. “By next summer, we will be in our new house [in Gaza],” she said. “It is God’s plan for us to return.”

Although the settlers like to credit God for hastening their potential return to Gaza, they have had significant help from earthly sources. Before the ceasefire agreement, Israeli forces built an extensive architecture of occupation in the Gaza Strip. Along what the IDF calls the Netzarim Corridor—a four-mile-long paved road that bisects the Strip’s northern third—they constructed more than a dozen military outposts and bases, equipped with air-conditioned housing units, showers, kitchens, and synagogues. (One Orthodox rabbi said that numerous Torah scrolls had been brought into Gaza.) Additional clusters of checkpoints and military inspection installations were also built across the Strip.

In mid-December, the Israeli news site Ynet published a puff piece on a “small retreat village” that the IDF had built in the northern Gaza Strip, outfitted with a desalination system, physiotherapy studios, a mobile dentist’s office, and a gaming room. “The space is really an island of calm hidden between the ruins of the strip,” the article crowed. “There’s even a café with a big espresso machine, popcorn and cotton candy machines like in the movies, and a lounge for treats like Belgian waffles and hot pretzels.”

“This,” the article’s headline stated, “is how the army is preparing for an extended stay in Gaza.”

For the Palestinians who remained in Gaza’s north, however, “this” meant only more suffering. Along with the constant bombardment from above, life became a nightmare of freezing conditions and hunger. As part of an openly stated strategy of ethnic cleansing aimed at eradicating the Palestinian presence in the north, Israeli forces systematically demolished entire neighborhoods, destroyed critical life-sustaining infrastructure, including hospitals, and deployed starvation as a weapon of war. The little humanitarian aid that was allowed to enter the Strip could hardly reach the people left in the north. Aerial footage of the once densely populated cities of Beit Lahiya, Beit Hanoun, and Jabalia show a landscape of total devastation, with mountains of gray rubble extending almost to the horizon.

For Weiss, this devastation was a welcome stage in a divine plan. In an interview with KAN, Israel’s public broadcaster, in mid-November, she revealed that during an expedition along the separation barrier to scout future settlement sites, she had contacted active-duty IDF officers with far-right sympathies who provided a military jeep to take them into the Strip, where they surveyed the site that had been the Gaza settlement of Netzarim. “We, the settlers, have all kinds of methods,” Weiss told KAN.

The next stage would be simple, she continued. Sometime in the coming months, they would attempt to bring many more Nachala activists into the IDF bases in Gaza; then they would refuse to leave. “What is happening right now is a miracle; we are fighting a holy war,” Weiss said. “A year from today, the people of Israel are back in Gaza.”

For his part, Netanyahu has repeatedly called the prospect of rebuilding Jewish settlements in Gaza “unrealistic.” But within the Likud, Netanyahu’s own party, not to mention his governing coalition, there is substantial support for the idea. According to KAN’s report on the Gaza settlement movement, an estimated 15,000 of the Likud’s roughly 60,000 primary voters belong to hard-line pro-settlement groups. When asked by KAN if there is a majority within the party that supports resettling Gaza, Avihai Boaron, a Likud member of Knesset, responded, “Yes, absolutely.”

The election of Donald Trump to a second term has given new energy to the settler movement’s already maximalist ambitions. At the Nachala event in Sderot, there was a widespread feeling that with Trump in office, the settlers, and the far right more generally, would have even freer rein. Standing in front of a banner promising to build “New Gaza”—a new, all-Jewish city on the ruins of what is now Gaza City—a man named Yaakov explained enthusiastically how a future that had once been unthinkable had, to his mind, become possible. “We are going to flatten all of Gaza and build a city on top of it,” he said. “If you asked me even six months [ago] about this, I would have said you were crazy.

For all the power that the settler movement has accrued within Israeli politics—and over the fate of Palestinians—the majority of the country has never supported the rebuilding of settlements in Gaza (more than half, according to recent polls, oppose it). But the success of Israel’s settler right has never derived from actual mass support. To the contrary, it is a textbook case of a vanguardist movement. The settlers built a lobby that learned to exert leverage within the Likud, while simultaneously transforming its own political representatives into parliamentary kingmakers. In the West Bank—the model for what the settlers hope to achieve in Gaza—the occupation has been entrenched as much through apparently unilateral settler action (creating facts on the ground and forcing the state to catch up) as by deliberate state planning.

Last February, a group of hilltop youth—known for attacking Palestinian shepherds and towns in the West Bank—managed to run through an IDF checkpoint and into Gaza before being tracked down by the army, while others attempted to construct an outpost in the IDF-designated buffer zone. That effort failed, but even with the ceasefire in effect, there remains the risk that a group of settlers, whether from Nachala’s ranks or further to their right, will try again. And while the withdrawal of most Israeli forces from the heart of Gaza has decreased the chances that the settlers will succeed in the immediate future, Weiss and her fellow militants are not wrong to think that time is on their side. As the settlers have often made clear—and as Weiss herself emphasized when she spoke to the crowd at the Sderot gathering—they are playing the long game.

“Today, there are 330 settlements in Judea and Samaria,” she said, using the settlers’ preferred biblical term for the West Bank, “and close to 1 million Jews beyond the Green Line. This was not born in a single day, and it was not achieved without struggle.

“We want to return to the Gaza Strip, to the inheritance of the tribe of Judah. We want the western Negev to extend all the way to the Mediterranean Sea,” she continued to applause. “And we will achieve this goal by the merit of everyone here and all of those praying for the return of the Jewish people to all its land.”

After Weiss had finished her speech and several other far-right activists had given short exhortations of their own, the settler militants climbed into their large white vans, strapped their many children into their car seats, and started toward the Black Arrow memorial. A single veteran Nachala activist named Hayim lingered in the parking lot, gathering the many signs that had been strapped to chain-link fences and wrapped around trees. He pointed toward the caravans, which remained parked in their place as the procession departed. The caravans, he explained, were not intended to be taken into Gaza that night; they were there to illustrate the movement’s commitment to resettling Gaza, step by step.

“At the end of the day, the government follows the people,” Hayim said. “The goal here is to make a groundswell that the government cannot ignore.”

More from The Nation

Morena and Claudia Sheinbaum Have Kept Up Mexico’s Move to the Left Morena and Claudia Sheinbaum Have Kept Up Mexico’s Move to the Left

Incumbent parties around the world keep losing to upstart challengers. Yet Mexico’s López Obrador defied the trend, handing off his presidency to Sheinbaum. What’s their secret?

How the Greens Became the Driving Force of German Militarism How the Greens Became the Driving Force of German Militarism

The Greens, founded as a pacifist party, are now enthusiastic cheerleaders for rearmament.

Elon Musk Does Europe Elon Musk Does Europe

As Musk wrote in a January post, “From MAGA to MEGA: Make Europe Great Again.”

Gazans Have a Message for Trump: We’re Not Going Anywhere Gazans Have a Message for Trump: We’re Not Going Anywhere

The president wants to clear the territory and take it for the US. But people here are adamant: "I will never, ever leave my land."

EU vs. US or People vs. Billionaires? EU vs. US or People vs. Billionaires?

Trump’s latest geopolitical moves are scary. But Americans and Europeans share a common foe.

Trump’s Phony Trade Wars Are Evidence of American Imperial Decline Trump’s Phony Trade Wars Are Evidence of American Imperial Decline

President’s bullying of allies yields symbolic results—but betrays substantive weakness.