What the Paiva Family Means to Brazil

In I’m Still Here, one Brazilian clan’s confrontation with the military dictatorship dramatizes the last half-century of Brazil’s democratic travails.

In the early 1960s, Brazil seemed poised for a progressive policy breakthrough. President João Goulart, a populist who had served as minister of labor under the nationalist government of Getúlio Vargas in the 1950s, sought to balance a cordial working relationship with the United States with an openness to the rising reformist tide coming from his own Brazilian Labor Party (PTB), peasants organizing in the countryside, urban labor unions, left-wing students, and beyond. Only a few years removed from the Cuban Revolution, many Brazilians harbored hopes that Latin America’s largest nation could achieve land reform and other structural changes to the country’s unequal social order at the ballot box. As Brazilians went to the polls in the 1962 congressional elections, the illusory threat of communism loomed large. Conservatives, The New York Times reported, “have tried to persuade the voters that unless their opponents are defeated, Brazil is in imminent danger of sliding under Communist control.” Increasingly concerned about Goulart’s ideological leanings, the administration of President John F. Kennedy devoted millions of dollars in covert spending to boost the opposition candidates.

Despite this, the PTB expanded its ranks in the Brazilian Congress. One member elected that year was Rubens Paiva, a charismatic civil engineer from the state of São Paulo who emerged as a rising star in the president’s party. He became one of the PTB’s leaders in Congress and helped oversee a parliamentary inquiry into CIA front groups used to destabilize the Goulart government. The strong electoral showing for the president’s party was further evidence that leftists of various stripes and a considerable segment of moderates were ready to embrace an agenda that promised to tackle the entrenched inequalities that have long defined Brazilian society.

But then, on April 1, 1964, with the active support of the US government, the Brazilian military intervened. Goulart fled the country, and a general was installed in his place—the first of five generals who governed Brazil over the next two decades of military rule. Paiva, along with many other elected officials broadly associated with the left, was stripped of his office a few days after the coup. A confidential US report in June 1964 characterized Paiva as a “leftist extremist” who “collaborated closely with Communists, though not a party member.” With Goulart’s fall, Paiva sought asylum at the Yugoslavian embassy before eventually leaving Brazil for France and then England. He took the risky step of returning home in early 1965, initially settling with his family in São Paulo and later in Rio de Janeiro. Working as an engineer and distancing himself from his country’s constrained political scene, he managed to afford his wife and five children a comfortable existence in one of Rio’s most desirable neighborhoods. What followed were years of relative peace for Paiva’s family, even as his country fell deeper into authoritarian repression.

I’m Still Here, the Oscar-nominated film from director Walter Salles, tells the story of the Paiva family’s ordeal. In so doing, it dramatizes the last half-century of Brazil’s democratic travails, from the cruel and repressive authoritarianism of military rule to the cautious, incomplete reckoning of the past three decades. Through the dire experience of one privileged, well-connected family, Salles presents a chilling portrait of what happens when a government declares war on its citizens.

Discussing his decision to make the film, his first since his 2012 adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Salles emphasized the drama of the Paiva family matriarch: “In the experience of one woman—Eunice Paiva, a mother of five—there was both the story of how to live through loss and a mirror of the wound left on a nation.” There was also a personal connection, Salles added: “I knew this family and was friends with the Paiva children. Their house remains etched in my memory. During the seven years we spent creating I’m Still Here, life in Brazil veered dangerously close to that past—which made it all the more urgent to tell this story.” Indeed, the film has stirred a national conversation about the brutal dictatorship that controlled Brazil for two decades, a dark period that former president Jair Bolsonaro has lamented was not violent enough.

In addition to its political dimension, the movie has drawn fresh appreciation for the quality of Brazilian filmmaking. The last time a Brazilian film garnered the level of international critical acclaim that I’m Still Here is currently enjoying was in 1998, when Central Station—another feature directed by Salles—was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film. That movie also garnered a Best Actress nomination for its star, Fernanda Montenegro, perhaps Brazil’s most revered dramatic artist. This year, Fernanda Torres, the heart of I’m Still Here (who also happens to be Montenegro’s daughter), became only the second Brazilian performer ever nominated for an Academy Award.

Torres plays Eunice, whose dawning horror at her family’s predicament provides the film’s emotional weight. The first time we see her, she’s floating in the ocean, her relaxation interrupted by the angry buzz of a low-flying army helicopter passing overhead. Eunice is not particularly political, but there is a clear sense of her own foreboding each time she notes the conspicuous signs of a militarized society: the chopper slicing across the sky, the cops at the checkpoint who harass the eldest Paiva daughter and her countercultural friends, a troop convoy speeding ominously past the beach as the Paiva family tries to relax on the sand. The time is around Christmas in 1970. The beachside Paiva home—warm, full of music and art, open and inviting—is always filled with family friends. Zezé, the live-in maid, is something like a third parent to the children, grounding and caring for them amid the household’s agreeable chaos.

Rubens, meanwhile, is the kind of dad who spontaneously decides to take the whole clan out for ice cream after dinner and plays a heated game of foosball in the middle of the night with a son who should be sleeping. Selton Mello imbues him with a sly sense of humor and a deep physical affection for his family and friends. But Rubens is also furtive: Through late-night phone calls, parcels exchanged with unseen individuals who show up at his doorstep but never enter his home, and fragments of hushed conversations with friends, it becomes evident that he is keeping something from his family. And then, on January 20, 1971, a game of backgammon between Rubens and Eunice is interrupted by a knock at the door. Their lives are changed forever in an instant.

Plainclothes agents of the state’s secret police are suddenly in the Paiva home, informing Rubens that he will be coming with them for questioning on some unspecified matter. Rubens is allowed to put on a suit and drive his own car—with an agent in the passenger seat—to some unknown location. Some of the agents stay behind to monitor the family; they seem more out of place than threatening. (It’s not shown or otherwise mentioned in the film, but some friends of the teenage Paiva children who happened to come by the house were taken in for questioning as well and only released days later.) The following day, with no news of Rubens, Eunice and her daughter Eliana are also brought in for questioning. In the back seat of a police car, she and Eliana are told to put on black hoods before they arrive at a dank army base, where people can be heard screaming and pleading. Eunice is ordered by an intelligence officer to flip through a thick binder of mug shots and identify anyone she recognizes, anyone her husband might have been in communication with.

Eliana was sent home after a day, but Eunice was detained for 12 days, forced to repeat the interrogation again and again. In a 2024 interview about his family’s ordeal, Marcelo Rubens Paiva, the only son of Rubens and Eunice and the author of the book upon which the film is based, stated that the reason his mother and sister were also taken in was either so that Rubens could be tortured in front of them or so that he could be forced to watch as they were abused. “Our ironic and paradoxical luck,” he asserted, “was that my father died quickly.”

The only sympathy Eunice encounters during her imprisonment comes from a young guard who tells her hurriedly that her husband is no longer there and, later, that he does not agree with the harsh orders he’s been tasked with carrying out. Eventually, an exhausted Eunice is allowed to leave. Her homecoming provides scant relief, as Rubens’s whereabouts remain unknown. Eunice saw his car at the base, but the security forces provide no answer as to where he’s been taken. Friends of the Paivas remain convinced that Rubens is still alive somewhere, that he is simply too high-profile for the regime to kill.

Eunice did not yet know what happened to Rubens, but US officials in Brazil did. “Paiva died under interrogation either from a heart attack or other causes,” diplomat John W. Mowinckel wrote in a February 11, 1971, memo. “When this becomes known (as it eventually will) it is certain that his friends will generate a violent and emotional campaign against the Brazilian government by every means possible—international press, letters to Senators Fulbright, Church, Kennedy, etc.,” he added, referring to the Democratic US senators increasingly attuned to the human rights abuses being carried out by US-backed dictatorships in Latin America.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Mowinckel was right: Paiva’s disappearance was covered in The New York Times and galvanized allies at home and abroad. In another report by a member of the US mission to Brazil, diplomat R.J. Bloomfield wrote that he had previously met the Paivas through a professor of Latin American history at Dartmouth, “an old friend of ours who is a good friend of theirs.” Bloomfield called the Paiva household the day Eliana was released to see “if there was anything I could do for her or her brother and sisters.” Bloomfield reported that Eliana “was in a highly emotional state and pleaded with me to do something on behalf of her parents.” While lending a modicum of support, he explained that “as a foreign diplomat it would be inappropriate for me to make any inquiries.”

Though Washington’s support for the military regime was mostly elided, the Paiva case added to mounting concerns within sectors of the US government and in civil society more broadly that, in the name of anti-communism, the United States was rubber-stamping atrocities in its hemisphere. “This is another example of irresponsible strong arm tactics and bungling by Brazilian security forces. The difference is that this time, when the facts become known, it will not be possible to sweep them under the rug. Confirmation of his death will raise one hell of a stink and once again embarrass the U.S. Government in its relationship with the [government of Brazil],” Mowinckel wrote, urging the Nixon administration to pressure the Brazilian government to hold “at least some of those responsible” to account. No such reckoning ever came for those behind Paiva’s death.

The Brazilian government’s official story was that Rubens had been taken from the security forces by armed left-wing comrades and then “killed in combat.” Eunice, in the film, is pained by the absurdity of the lie. She receives the news of her husband’s death just as she is about to take their children out for ice cream, a crushing reminder of happier times. This is the scene in I’m Still Here that has been widely hailed as the finest moment in Fernanda Torres’s remarkable performance. Sitting there as her children enjoy their dessert, Eunice looks around at the other happy customers and displays the quiet certainty that her old life is gone, even as she insists on keeping up appearances for her children’s sake. In that wordless moment, she seems to decide that she must act: Her family now depends on her. Torres’s sharp features convey a torrent of emotions—resignation, confusion, sorrow, determination. It is a powerful dramatic feat.

Eunice’s suddenly dire financial predicament adds to the upheaval; she cannot access the family’s bank account without Rubens’s signature. In a move that surely took considerable planning but happens abruptly in the film, Eunice opts to relocate her family to São Paulo, her hometown, where her parents can help with the children so she can go back to college and improve her professional prospects. The last act of the film takes place decades later: The first jump is to 1996, at which point Eunice has successfully reinvented herself. She is now a lawyer specializing in Indigenous affairs and a consultant for Brazil’s federal government, the World Bank, and the United Nations. Along with disappearing hundreds of political dissidents like her husband, Brazil’s military regime carried out multiple violent assaults against the country’s Native peoples. The centerpiece of this emotional epilogue is Eunice’s acquisition, 25 years later, of an official government death certificate for Rubens.

The context for this breakthrough, which the film omits, was the election of Fernando Henrique Cardoso in 1994. Acting on the demands of the victims’ families, Cardoso supported the passage of Law 9.140, which officially acknowledged the state’s responsibility for the deaths, disappearances, and human rights violations during the dictatorship. A key aspect of this legislation was the creation of the Special Commission on Political Deaths and Disappearances, which sought to identify those killed or disappeared due to their political activities, locate their bodies, and help families with reparations. Prior to this, many families—like the Paivas—had never received a death certificate, which prevented them from performing basic civil acts like completing a will or filing for a pension as a widow or widower. The law represented not only a legal response but also a personal one for Cardoso, who expressed a deep emotional connection to the victims. A former professor at the University of São Paulo who fled for Chile after the 1964 coup, Cardoso had been friends with Rubens and helped with his 1962 campaign. That relationship might have been mentioned in the film as a reminder of Paiva’s connections and stature on the left before the coup violently interrupted his political career. In addition to being a father and a husband, he had been a politician eager to wield power in pursuit of progressive aims. “I am hurt to this day by the loss of Rubens Paiva,” Cardoso said during the signing ceremony for Law 9.140. “I am hurt to this day by the sad smile of my former student Vladimir Herzog,” a prominent journalist who died at the hands of security officials in 1975.

The film’s final jump happens in the last 20 minutes. It is now 2014. An elderly Eunice, played by Torres’s mother, is surrounded by her grown children and grandchildren. She has been left without speech after a years-long battle with Alzheimer’s, but her family is happy, settled. The viewer hears from a television broadcast that the work of the National Truth Commission is underway, a body created by President Dilma Rousseff, herself a former member of a guerrilla organization who was arrested and tortured in 1970. In the film’s last moments, Eunice sees Rubens’s face flash on the screen as one of the victims officially recognized by the commission. She is struck, clearly recognizing her husband’s face after so many years. It is a tragic, yet ultimately romantic, end to a searing film fundamentally about human endurance in the face of abject cruelty. Eunice, who passed away in 2018, surely would have been pleased by the wide audience of I’m Still Here and by the renewed debate among members of Brazil’s Supreme Federal Court as to whether those responsible for Paiva’s death should in fact be protected by a blanket amnesty issued by the dictatorship in 1979. Less encouraging is the sustained popular support for far-right extremists in Brazil who are eager to use the return of Donald Trump in the US to launch a comeback bid in next year’s presidential election. The stakes for Brazil’s democracy remain uncomfortably high as the country continues to grapple with the darkest chapters of its not-so-distant past.

The film’s political impact ultimately stems from the Paiva family’s disorientation and pain—and they come to represent the experience of a wide swath of victims under the regime. But Salles avoids more pointed political critiques, either of US complicity in the dictatorship or of those Brazilians who, then and now, support state violence wielded in the name of anti-communism. The viewer unfamiliar with Rubens Paiva does not come away from the film with any firm understanding of his political background. This doesn’t diminish the movie’s potency, but it does lead one to wonder how the film would have been received if Paiva’s left-wing background had been more pronounced. In a moment of deep political polarization, in Brazil and elsewhere, it is possible that I’m Still Here would not have been a box office sensation had it been seen as a partisan statement. The film excels at rendering a family and nation distressed by reactionary violence, even if it has less to say about the origins of that crisis. In the end, it’s worth asking: How would Rubens Paiva, the political brawler, have wanted his story told?

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

The Best Albums of 2025 The Best Albums of 2025

From Mavis Staples to the Kronos Quartet—these are our music critic’s favorite works from this year.

Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology Forrest Gander’s Desert Phenomenology

His poems bridge the gap between nature’s wild expanse and the private space of one’s imagination.

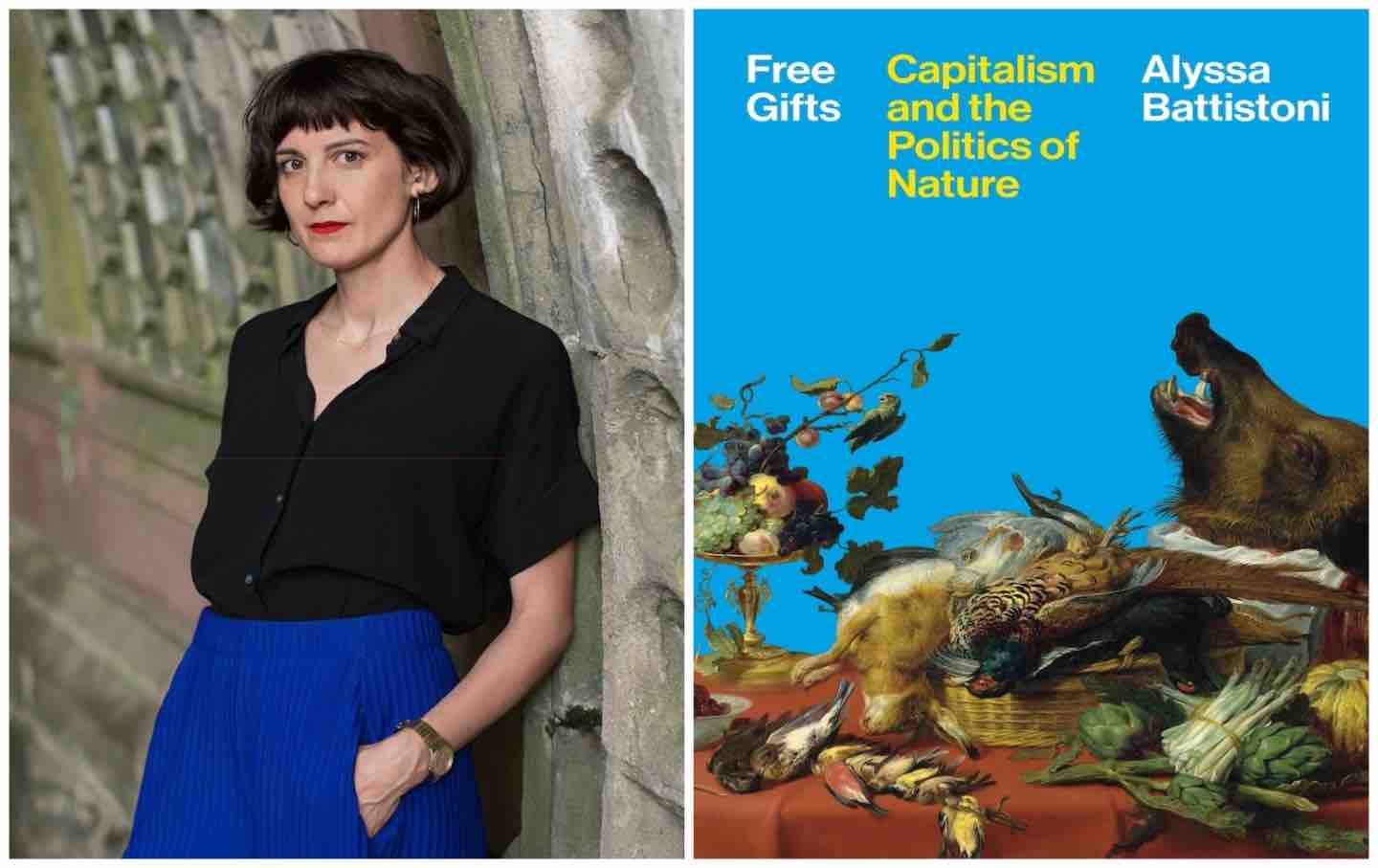

Capitalism’s Toxic Nature Capitalism’s Toxic Nature

A conversation with Alyssa Battistoni about the essential and contradictory nature of capitalism to the environment and her new book Free Gifts: Capitalism and the Politics of Nat...

Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time Solvej Balle and the Tyranny of Time

The Danish novelist’s septology, On the Calculation of Volume, asks what fiction can explore when you remove one of its key characteristics—the idea of time itself.

Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull Muriel Spark’s Magnetic Pull

What made the Scottish novelist’s antic novels so appealing?

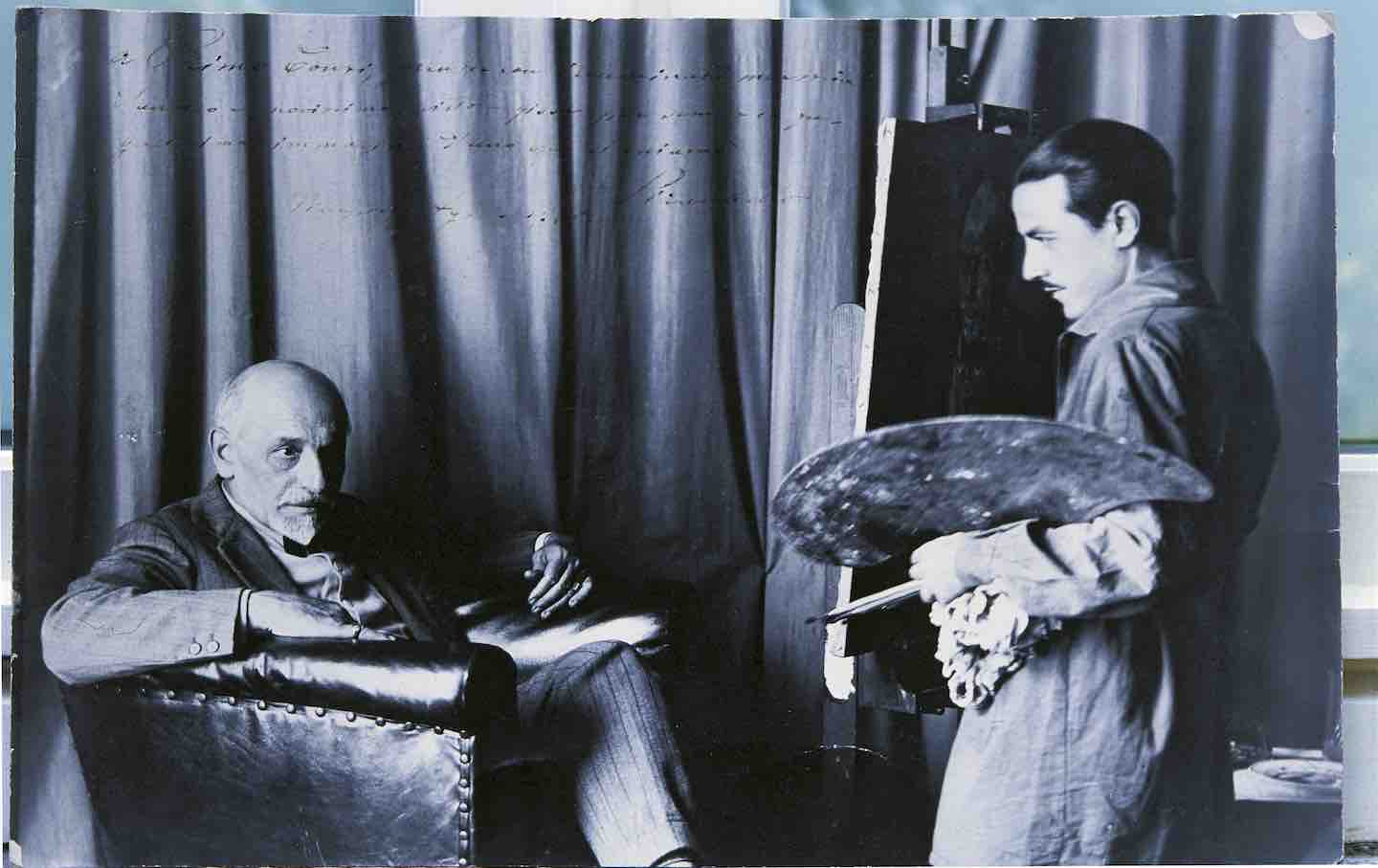

Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men Luigi Pirandello’s Broken Men

The Nobel Prize-winning writer was once seen as Italy’s great man of letters. Why was he forgotten?