Vampire Weekend

What I learned at Bryan Johnson’s “Don’t Die” summit is that optimizing yourself like artificial intelligence is not only futile. It is also very expensive.

How I Didn’t Die: My Day at Bryan Johnson’s Immortality Summit

It turns out that optimizing yourself like artificial intelligence not only won’t ensure that you live forever. It is also very expensive.

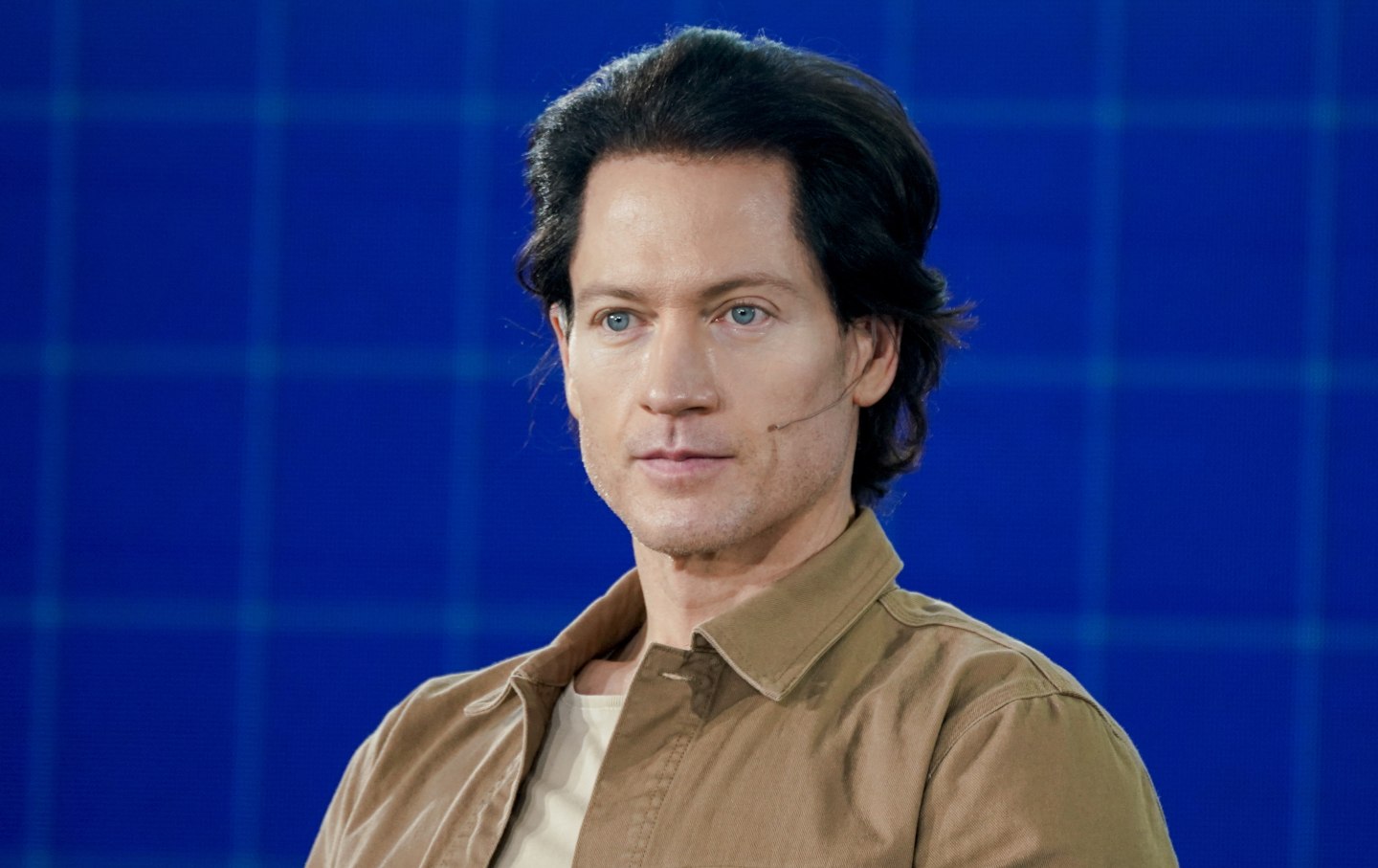

Bryan Johnson, founder and chief executive officer of Kernel Holding SA.

(Kyle Grillot / Getty Images)

It’s 9:30 am, and I am doing calisthenics on the lower level of the Javits Center. I am at New York City’s “Don’t Die” Summit, a conference focusing on anti-aging and life extension organized by tech millionaire Bryan Johnson. A 48-year-old ex-Mormon, Johnson has spent years proselytizing his $2 million-a-year diet, exercise, and medical testing regimen as the key to living long enough to enjoy “our shared future with AI.” Now, like a circuit rider, he’s taking his show on the road, preaching the gospel of living forever in Los Angeles, New York, and Miami. Johnson and his longevity business represent how tech money, scientific half-truths, and optimization culture all converge into a new religion for those wealthy enough to worship at its altar.

The day’s agenda promises many pleasures. We will begin with a lecture titled “Life System and Habits to Build your Future Self” led by Johnson and a medical doctor named Mike Mallin. Next is a lunch provided by Blueprint, Johnson’s proprietary health protocol, which offers supplements, meal plans, and fitness guidance. Then comes a session called “Roast My Protocol,” in which attendees can get expert feedback on their personal health routines, followed by a singalong and dance party. Between 3 and 3:30 pm, according to the schedule, we are supposed to “make new friends.” All of this for the low, low price of $249—the cost of a general admission ticket at the early-bird rate. (But don’t fret, you can pay up to $1,799 for an ultra-premium ticket, which gets you a gift bag and an unspecified “Exclusive Don’t Die Experience” with Johnson himself.)

For now, I focus on “Fitness Bioage Testing,” a series of self-administered physical challenges said to reveal our biological (as opposed to chronological) age. I sit in a sea of black yoga mats, each equipped with a pink tape measure, a wooden ruler, and a grip-strength testing apparatus. An energetic young woman, shouting over a generic techno track, cues us through seven fitness challenges designed to test our strength, balance, reaction time, and flexibility. We are not to rest or modify the exercises in any way—though with only one instructor and probably over a hundred of us, who would know? The participants—among them, many gorgeous women clad head to toe in Lululemon—earnestly perform push-up after push-up. After each exercise, we dutifully record our results on the “Don’t Die” placards we received when we checked in upstairs using a tiny Sharpie. This numerical data, once entered into the Don’t Die phone app, will allow it to calculate our body’s “true” age.

My results are disappointing. Not only am I out of shape—I am reluctant to compromise my journalistic mission by becoming repugnantly sweaty an hour into the day’s events. I do only two push-ups before giving up, then illegally use my hands to support myself during the “sit-rise” test. The Don’t Die app tells me my biological age is 53.3, even though, in real life, I am only 38. Some individual test results are even more worrying, implying that I am an “adult in [my] 70s,” even as what the placard whimsically calls my “waste-to-height ratio” likens me to a “female in [my] teens.” As a 29-year-old graduate student in Germany, I was once tempted by a novelty T-shirt reading, “So gut kann Man mit 60 aussehen!” (Here’s how good a 60-year-old man can look!), with a red arrow pointing to the wearer’s face. The results of the Don’t Die Bioage Test are making me wish I’d bought it after all.

Engrossed in detangling the tape measure that is supposed to help assess my flexibility, I miss the moment when Bryan Johnson himself enters the room. He is shorter than I imagined, but even more waxen-looking. Smiling beatifically, he works the crowd, followed at every step by a glowering man in a skinny black tie. After administering a few high fives, he departs, wishing us luck (“hope you’re all young!”) and promising to see us again at the dance partyscheduled for the afternoon. As we toil on our mats, the workout leader reminds us that, appearances to the contrary, “Bryan is here. Bryan is watching.”

We see Johnson again shortly, at the day’s first lecture. He is onstage, beaming, in front of a thousand-odd people, all eager to learn how to live forever. From where I sit, behind rows of $600-and-up Premium seats, he is a speck. He wears a T-shirt emblazoned with the name of his movement, “Don’t Die,” and baggy black pants that would be right at home in a Delia*s catalogue from 1996. Next to Johnson is a very fit man in his early 50s. He also wears a “Don’t Die” T-shirt and has the blank, unsmiling blue eyes and faux-casual cadence of an experienced salesman. This is Johnson’s “lead doctor,” Mike Mallin—Dr. Mike for short. Once an emergency room physician, he “left academics for private practice in 2017” and now runs a concierge medical service called Wild Health.

Today, Dr. Mike has something he must urgently confess to us, his thousand closest friends: he has a love-hate relationship with Extra Toasty Cheez-Its™. After a recent work trip, his overtired brain made him buy an entire bag of this product and consume half of it at once. Luckily, he soon realized what he was doing, and tossed the remaining Extra Toasty Cheez-Its™ into the trash, where they belong. Johnson is magnanimous. Dr. Mike is not in the throes of an eating disorder; he has just suffered a temporary setback. “It’s OK, Dr. Mike,” Johnson says. “We accept you. It’s OK.”

Taking their cues from Johnson and Mallin, audience members now take the mic and confess to their own food-related “debaucheries,” as Johnson calls them. One man worries that an upcoming trip to Vegas will provide him with too many opportunities to imbibe. “My weakness isn’t alcohol,” he reveals. “It’s free stuff.” Another man, who calls himself “Boston Jim,” tells the group his father died 10 days ago, and as a result, he ate a “half of a half-gallon of ice cream”—even though, normally, he follows a strict protocol that has helped him lose 47 pounds. A third man, who identifies himself as Alex Morozov, has trouble staying on topic. He congratulates Johnson on his work, and then, apropos of nothing, boasts that he recently went to a MAHA press conference and “even asked a question.” But where, Johnson probes, is the debauchery in that? Morozov hedges, then discloses that he has made his apartment a “sugar-free zone,” affixing stickers to this effect to many household surfaces. With further prompting, he admits he once had high triglycerides. “Well, what led to the high triglycerides?” Johnson asks. Morozov finally admits that his weakness is “all kinds of delicious cookies, bars, [and] chocolate.” But even this is not enough for Johnson, who presses him to reveal the number of indulgences per day. “Five, six, seven, eight,” Morozov says. The room roars with laughter. “Yeah, well, we accept you. We love you. Good job. It’s OK,” Johnson tells him.

This public display of vulnerability acts as Johnson’s segue into an extended sales pitch for Blueprint, a lifestyle brand he founded in 2021 after earning $800 million from the sale of his payment-processing company, Braintree Venmo, to PayPal. He reassures us that all humans are fragile and fallible, and at the mercy of what his website calls our “rascal self”—the part of our mind that tempts us to eat immoderately, drink to excess, and stay up until the wee hours. “You never want to put yourself in a situation where you have to make a decision,” Johnson warns. “You want this decision to be made ahead of time. You want life habits and life systems that run automatically.” When we’re as tired as Dr. Mike was when he bought the Cheez-Its, Johnson believes, there’s no chance our brains will keep us on the straight and narrow. The purpose of Blueprint is to remove the possibility of error by outsourcing all decision-making to a customized algorithm. A slide projected onto the auditorium’s screens reads: NEVER LET YOUR MIND DECIDE.

Data is paramount for Blueprint, which relies on a tight feedback loop between meticulously tracked biometric measurements and the interventions they dictate. Johnson says one of his goals is to move the world of health and wellness “away from storytelling,” toward “biomarker and data measures.” Only data will allow humanity to move beyond listening to our minds and bodies, transforming us into optimized meatbots. Dr. Mike agrees: A given diet or sleep regimen may leave you feeling great, but that’s not what “counts,” literally. “ ‘I feel great.’ But are you great?” he asks rhetorically. “Like, are you testing the things that matter?” Our sensations are framed as untrustworthy manifestations of “Rascal Brain” that only cramp our algorithmic style. It is the body’s data, not its subjective impressions, that actually reflect our state of being.

This techno-solutionist approach to health and wellness epitomizes what Frankfurt School philosopher Max Horkheimer, writing in the 1940s, called “instrumental rationality,” a form of reason that never asks “why” but only “how.” Instrumental rationality searches for the most efficient means to a given end without questioning whether that end is even worthwhile. This narrowly defined rationality requires a rigid compartmentalization of a type I recognize in Johnson’s descriptions of himself as a collection of warring personae. During the day’s first lecture, for example, he recounts how during his “wind-down time” from 7:30 to 8:30 pm, Ambitious Bryan torments a beleaguered Sleep Bryan, who must already contend with Dad Bryan and Debaucherous Bryan. Johnson clearly prefers following inflexible instructions to actually wrestling with these demons—much less wondering whether they might have something useful to tell him after all.

For Horkheimer, instrumental rationality, in its myopic quest for optimal methodologies, allows humans to let themselves off the hook even for genocide. If you restrict your attention to the steps of your algorithm, each individual decision may seem sensible and value-neutral. But in the aggregate, these micro-decisions can lead to monstrous results—up to and including the Holocaust, the postwar Frankfurt School’s central example of modernity run amok. On the surface, Johnson appears to be asking age-old questions about how to find “the good life.” But in practice, his activities boil down to Horkheimer’s instrumental rationality, a meaningless striving toward longevity that never wonders whether an inhumanly long life is even worth pursuing.

After the revelation that enlightenment requires entrusting our lives to algorithms, it is time for some health advice. To live a long time, we are told, we must go to bed on time, sleep well, eat a balanced diet, and exercise regularly—all common-sense and even data-backed suggestions. But Johnson and Dr. Mike take things a step further—focusing, for instance, on a metric called VO2max, the maximum amount of oxygen the body can take in at maximum exertion. To optimize VO2max, Dr. Mike recommends high-intensity interval training (HIIT), but adds that, to properly measure this aspect of your conditioning, you need a specialized and costly machine.

The slide behind Dr. Mike displays a chart correlating VO2max with mortality. Later, Johnson cites “a paper out of Yale” whose findings coincide with his own “research.” It is odd to hear these appeals to Ivy League authority from a MAHA and RFK Jr. affiliatealigned with a president who “loves the poorly educated” and a vice president who believes that “universities are the enemy.” Beyond this off-brand political subtext, the VO2max interlude establishes a pattern that holds throughout the day. Each piece of health advice comes with an asterisk: If we can’t trust our subjective impressions, each intervention’s efficacy must be assessed materially—usually, with expensive machinery.

During the same lecture, Dr. Mike describes the “pace of aging,” which he says we can control with the right algorithms. He calls to mind the motivational speaker Ed Mylett, who once claimed thathe lives “21 days per week” by dividing every 18-hour period into three “days.” Johnson’s presentation of his core principles is similarly phantasmagoric. A slide lists THREE THINGS TO MASTER: first “life habits,” then “daily habits,” and finally “Don’t Die.” It doesn’t seem possible for sheer enthusiasm to overcome the abyss separating regular exercise and good sleep from the goal of living forever, yet that is exactly the leap Johnson asks us to make.

Johnson has already aligned himself with RFK Jr. and MAHA, so it’s not surprising that “Don’t Die” embodies the techno-libertarian, “small government” ethos that has defined the second Trump administration: privatizing public goods while slashing government spending, including on scientific research. During the morning session, Dr. Mike announces a venture launching in March called “Don’t Die Certified,” a bid to “map the food-ome of the United States” in imitation of the NIH-funded Human Genome Project. To uncover the American “food-ome,” Johnson hopes to identify the toxins he thinks pervade our food supply—a project that recalls RFK Jr.’s crusades against processed foods and pasteurization by blending legitimate concerns about industrial food production with pseudoscientific paranoia.

The business model for “Don’t Die Certified” does not rely on federal funding but on crowdsourced and for-profit contributions. The plan Johnson articulates is simple on its face: First, community members will donate $100 toward testing a specific product. Once a threshold of $1,000 is reached, this product can be tested in a lab. The results will be shared on social media, where companies will be invited to “claim their profiles,” and supposedly reimburse the testing costs. When they do so, the initial donors will receive $110, profiting from what Johnson argues should have been the manufacturers’ responsibility all along. Why would companies play along? Would people be guaranteed to get their money back if they didn’t? Johnson never explains.

Leaving aside the question of enforcement, this form of “community action” privileges for-profit investment over solidarity and mutual aid. In the same vein, Johnson proposes later in the same session that each of us remove microplastics from our own water supplies by buying reverse osmosis filters for “just 200 or 300 bucks on Amazon.” In keeping with the instrumental rationality of “Don’t Die,” there is no discussion of whymicroplastics pervade our environment or how we might address this crisis systemically. Instead, salvation comes through personal consumption—recording data in the Don’t Die app, purchasing Blueprint-branded tests, and installing home filtration systems, some of them conveniently sold by vendors awaiting us just outside the auditorium. This theoretical symbiosis among various profit-seekers also explains Johnson’s directive that we use the summit to “make friends.” He means it, of course, only in the Dale Carnegie sense.

We speed through the rest of the session, dropping the portion on women’s health for lack of time—we’ll return to it during “Roast My Protocol,” Johnson promises. Lunch provides an opportunity to sample Blueprint Fresh Meals, available for weekly doorstep deliveryat $15–20 per plate. I join a large, disorderly crowd waiting for food at the “lunch area.” There is no place to sit, so eaters cluster on the floor and on the few couches scattered along the edges of the convention space. A Don’t Die employee corrals us toward makeshift food distribution stations, shouting that premium ticket holders can skip the lines by heading to the VIP lounge. (The VIP food, though, won’t be any different from what’s on offer here: It’s “the same thing, just less crowded.”) Rumor has it that steak was available earlier, but quickly ran out, leaving only tofu. One woman is irritated at this choice of meat alternative: “Isn’t tofu, like, genetically…” she begins, then trails off.

Based on the contents of my lunch box, I am not sold on Johnson’s bold proposal that I eat cold, vegan food until the 25th century. The “Adobo tofu salad” is bland and unpleasant. The tomatoes taste like plastic, while the “chimichurri” tofu manages to be tough and soggy at once. The kale wilts sadly, unable to withstand a dressing bitter with spices over-steeped in oil.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Put bluntly, this food does not bespeak $250-plus worth of exclusive health insights. Its closest cousins are the “health bowls” available at fast-casual establishments across our great nation. When I inquire if the packaging is made of plastic, a Don’t Die event director informs me it’s actually “recycled potato starch” that, incidentally, was incredibly hard to source.

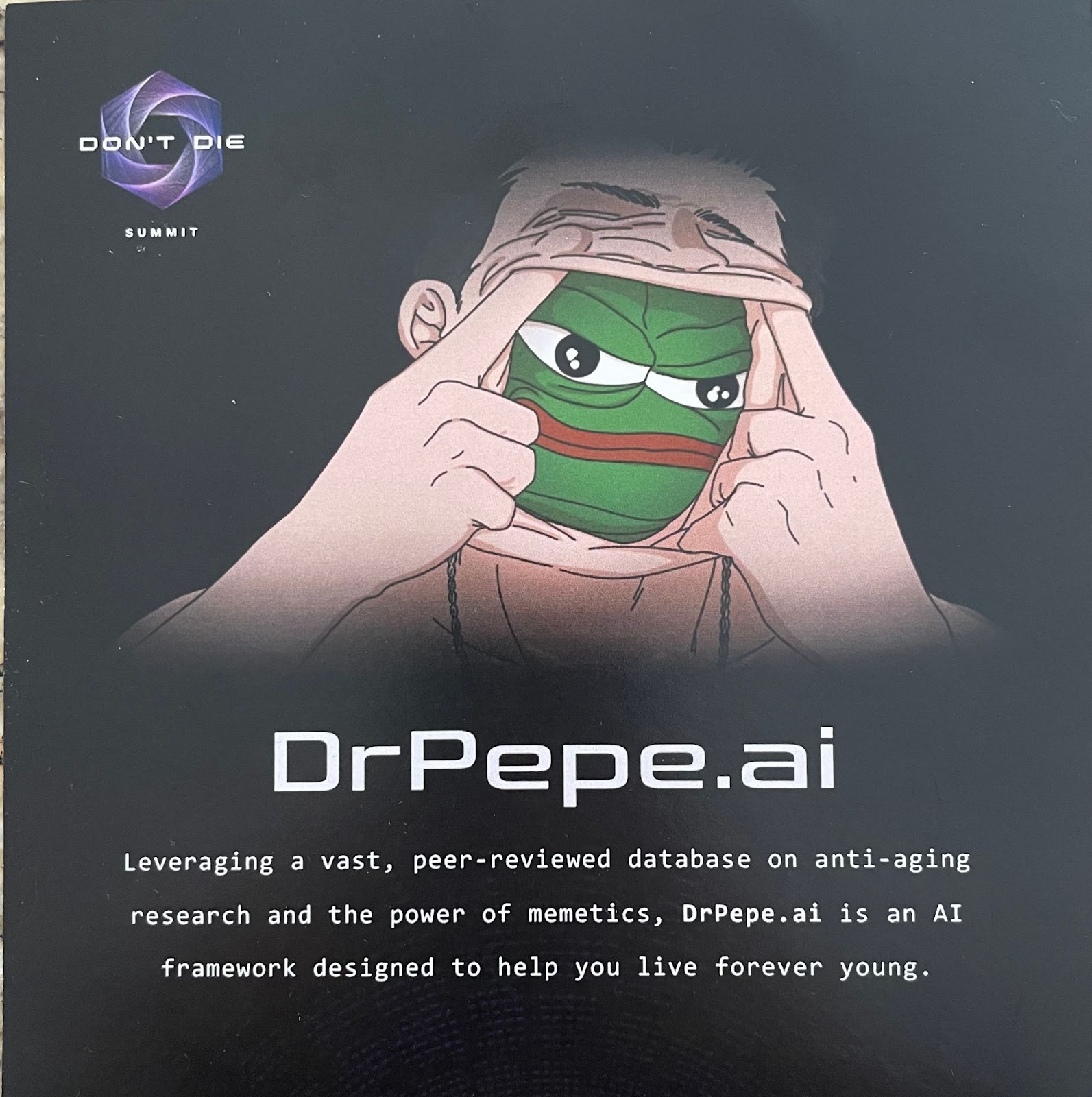

After lunch, I wander the convention space, chatting with vendors. The brands Johnson has chosen to platform fall into three categories: purveyors of lifestyle goods; biomedical testing companies that want your genes or blood; and longevity-promoting treatments. I am magnetically drawn to a booth advertising the services of “Dr. Pepe,” an AI-powered diagnostician represented by an image of a man tearing his face apart in the manner of the late-1990s shock meme known as Goatse. Emerging from behind this crumpled human visage is Pepe, the cartoon-frog symbol of the far right and, lately, a variety of cryptocurrency called memecoin.

The specific connections among these elements are left as an exercise to the consumer. All I manage to glean from the smirking Dr. Pepe rep is that the underlying AI is trained on “peer-reviewed longevity research authored by PhDs” from the types of prestigious universities Trump, JD Vance, and others have spent so much time denigrating. The image of Pepe, I’m told, is innocuous Gen-Z bait—and indeed, many of the summit attendees are quite young. After trading in the associated memecoin, Dr. Pepe’s founders evidently settled on the frog as an “edgy” way to bring hip young incels into the longevity fold—where their precious bodily fluids can presumably be harvested by their deep-pocketed elders.

My conversation with the Dr. Pepe rep leaves me feeling dazed, or perhaps undercaffeinated. I decide to try some of the mushroom-infused coffee I’ve seen people carrying around all day. Standing in line for my Styrofoam half-cup of an instant brew called Daily Dose, I chat with an affable guy toting around a camera and tripod. He is a “content creator in the mental health and wellness space” who is here courtesy of Nucleus, a company that combs through paying clients’ genomes for “health insights.” I ask if he’s had his own genes tested, and he says “not yet.” We agree that doing so seems creepy and possibly needlessly depressing, since genetic testing could reveal propensity to illnesses with no cure.

People crowd around the entrance to the auditorium, and I join them. It’s almost time for our second Johnson-led session, “Roast My Protocol,” and I’m hoping to snag a good seat. As we wait, I get to talking with a tall man in a beige vest who tells me, unprompted, that Blueprint changed his life. Johnson gets a lot of hate, he says, because people think he’s only out for himself—another narcissistic fat cat spending his wealth only on himself. But Johnson, unlike Jeff Bezos or Peter Thiel, is a noble man of the people, Beige Vest thinks. He credits Blueprint with improving his “mental acuity” and enabling “better communication,” attributes he worries are declining as he ages. I ask, if Johnson is legit, why he calls his proprietary EVOO “Snake Oil.” Beige Vest replies instantly: Johnson has a “dark sense of humor.”

We part ways as we enter the auditorium, where I sit down next to a laid-back man with dark curly hair and blue-light-filtering glasses. He explains that he’s only there because his friend, an early convert to the creed of Bryan Johnson, had an extra ticket. Like those sad couples where the husband flies business class but leaves his wife to languish in coach, my neighbor is stuck in steerage while his friend kicks it in Premium. Despite his claim that he’s just tagging along, he, too, professes devotion to Blueprint, particularly its sleep-related recommendations.

During “Roast My Protocol,” Johnson and Dr. Mike present more basic health advice peppered with recommendations for esoteric screenings. Johnson mentions he has had “multispectral imaging” to test his skin for sun damage. Later, I research this diagnostic tool and learn that dermatologists don’t provide it as a matter of course, though it’s available at some boutique practices for about $100. Most prohibitive is the cost of remediating any UV damage the imaging uncovers: a treatment called Broadband Light Therapy, for instance, can run $300 to $600 per sessionand, being cosmetic, would not be covered by insurance.

About forty-five minutes later, we finally get to women’s health. This segment is led by a thin, pale 29-year-old woman with masses of shiny brown hair and a fun Australian accent. This is Kate Tolo, the other half of the Bryan Johnson PR machine. Tolo actively welcomes the lack of agency Johnson’s protocol entails. In a 2024 interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, she notedthat the regimen allows you to stop “feeling like you have ownership over your own body,” which instead becomes a science experiment subject to successive measurements and interventions.

“Kate,” as Johnson calls her, has no medical training, but presents herself as an expert on female health optimization. Her lecture focuses on diet during different parts of the menstrual cycle. In her telling, the lives of biological women are reduced to our status vis-à-vis menopause: We are either pre-, post-, or peri-menopausal, with any possible pregnancies a slight deviation from this iron path. My neighbor is impressed and wishes he could send the accompanying slides to his mother.

After Tolo is finished, Johnson has a surprise for us: His mother and stepfather are here, ready to testify to the joys of Blueprint. Johnson’s mother is petite and soft-spoken, brimming with enthusiasm for her son’s program, which she says cured her pre-diabetes: “I’m so grateful to be here, so happy for what Brian is doing,” she gushes.

Next is a Q&A that reveals both the aspirational nature of Johnson’s program and its fundamental limitations. Queries range from the practical (“Are seed oils bad?”—yes, but only when cooked) to the intimate: Someone asks whether “jerking off before bed” is beneficial for sleep. Dr. Mike is evasive, saying there is no evidence for “semen retention” as an effective longevity strategy. Another attendee has a request: “Please talk more about female health insights, which differ vastly from male ones.” This area of inquiry, after all, “is under-researched and under-represented.” Neither man addresses this concern—indeed, it has been pre-deflected by Tolo’s earlier assertion that “men and women are more similar than you would think.”

The questions telegraph the audience’s worries about applying Blueprint to their own imperfect lives. Hardly anyone, it seems, feels they can follow the program as Johnson does—by expending infinite resources and monomaniacal dedication. Someone asks if they should quit a demanding corporate job they can’t perform without ADHD medication. But before this question can be answered, a man appears onstage and starts belting “I Wanna Dance with Somebody.” As the summit materials portended, it’s time for the singalong. I back away.

The relatively depopulated scene outside the auditorium allows me to approach the Blueprint booth, which has been mobbed all day. I try a glass of bright-yellow “Longevity Drink” in what I’m told is pineapple-yuzu flavor. A nurse practitioner who samples it alongside me agrees that the concoction tastes vile, then brightens as she reads the packaging and discovers that the ingredients match up with her dietary recommendations to her patients.

By now it’s 4 pm and I am desperately hungry. Luckily, I brought a PB&J—a debaucherous combination of seed oils, carbs, and sugars. As I scarf down my snack near the phone charging station upstairs, I overhear the lamentations of summit-goers dissatisfied with their $700 Premium tickets. Joining their conversation, I learn that they are “wellness specialists” who found most of the advice on offer far too basic. One woman, a “longevity coach,” says the summit was “a waste of my time and definitely a waste of my money.” I ask the group: What’s “premium” about the Premium ticket? “Nothing,” an acupuncturist replies. “You sit on the floor and eat some lunch you could have gotten anywhere.” The longevity coach remarks acidly that all her Premium ticket got her was a seat in the front row, where she had a fantastic view of Johnson’s dyed hair.

As the summit winds down, I’m left with some troubling questions about Johnson’s vision—even for those privileged enough to insulate themselves from the slings and arrows of outrageous toxins. By his own admission, he goes to bed each night at 8:30 pm, hungry and upset because he hasn’t eaten at the very least since noon (“I’m a big fan of multi-day fasts,” he says). He is beset by assorted Problem Bryans and so fixated on food that, as he reveals in his Netflix documentary, the moment when he takes his last bite is the “saddest part of my day.” If you follow his regimen, you may wake up with your arteries perfectly aligned thanks to ideal sleep posture, but what have you really gained beyond satisfaction in your own virtuousness? If you continue with Blueprint, every day of your long, long life will involve hundreds of pills, painful medical testing, and endless calorie restriction—which, as documented by researchers studying victims of starvation, eventually makes you insane.

Johnson’s immortality project is thus totally recursive, since any surplus energy must be reinvested in producing yet more energy. Maybe this is what businesspeople call a “growth mindset,” but to me, it just sounds like a scam. Having abandoned Mormonism, Johnson has developed a belief system no less rigid or ecstatically religious. (To their credit, some of the people I encountered at Don’t Die are aware that Blueprint separates practitioners from humanity rather than helping them “make friends.” One man describes the program as a “trade-off,” that, in exchange for the prospect of longevity, takes away life’s pleasures—from beers shared with friends to late-night pizzas with roommates.)

The horizon of Johnson’s longevity project is also very bleak. Johnson’s fixation on living until the 25th century and his advocacy for algorithmic decision-making mark Blueprint as preparation for the Singularity—a kind of technological rapturein which artificial intelligence allows humanity to transcend its biological limitations. During the morning lecture, my seatmate told me his journey toward Blueprint began with reading Yuval Noah Harari’s Homo Deus, which presents longevity as humanity’s defense against technological obsolescence. Johnson himself is clearly rehearsing for this future. He describes training his family to correct each other’s posture with the sound “zip,” a habit that began when his children noticed him standing “ramrod-straight” and declared, “Dad’s like an AI.”

It’s 5 pm and snowing heavily as I make my way to the exit. I overhear a young woman telling her friends, her voice hesitant: “I guess this was ever so slightly overpriced?”—laughable from my perspective, as a severe understatement. Even at the Premium tier, the summit’s health “insights” were either overly familiar or extravagant and outlandish. The most daring proposal I heard all day was that we can save our messy human selves from technological obsolescence by capitulating to algorithms in advance. Is that a good idea? In keeping with this authoritarian moment in American history, what Johnson’s Blueprint and its commercial ecosystem does, ultimately, is invite us to understand our own dehumanization as a form of empowerment.

More from The Nation

“We’re Living Through Hell”: What Trump’s Anti-Trans War Really Means “We’re Living Through Hell”: What Trump’s Anti-Trans War Really Means

When hospitals suddenly stop treatment for trans patients, real people are harmed: “I was sent links to suicide hotlines instead of a prescription.”

A Half Century of Failure to Reform the FBI Has Gifted Patel With Alarming Power A Half Century of Failure to Reform the FBI Has Gifted Patel With Alarming Power

Fifty years ago, lawmakers started lifting the lid on the shocking abuses of the new Bureau chief’s most famous predecessor. The trouble is, very little changed.

Why Hasn’t Trump Already Closed the Department of Education? Why Hasn’t Trump Already Closed the Department of Education?

Maybe because its support for students is popular with Republicans as well as Democrats. And because cutting that funding would blow a big hole in the budgets of red states.

Shield Laws Are the Fault Line in the Battle Over Abortion Access Shield Laws Are the Fault Line in the Battle Over Abortion Access

New York’s shield law was designed to protect providers mailing medication abortion pills out of state. But a New York provider is facing legal action in Louisiana and Texas.

Javier Milei’s Crypto Scandal Is Part of a Larger Network of Grift and Graft Javier Milei’s Crypto Scandal Is Part of a Larger Network of Grift and Graft

The Argentinian president faces impeachment charges for endorsing a crypto rug pull, via the same network that apparently launched Melania Trump’s memecoin.

The “Teenage Dream” in an Era of Isolation The “Teenage Dream” in an Era of Isolation

Curfew restrictions and the policing of public spaces prevent teens from “getting into trouble.” But to some, it feels like it’s preventing them from getting anywhere at all.