Trump Is Fumbling the NLRB. But Amazon Workers Can Still Build Momentum.

Amazon Teamsters’ December strike was the biggest in the company’s history. What does their future look like under Trump 2.0?

Picket signs lie on the ground as Amazon workers organized by the Teamsters Union go on strike in front of the DBK4 Amazon facility on December 20, 2024.

(Andrew Lichtenstein / Getty Images)

For five years, Vanessa Valdez has shown up for work each morning as a driver at Amazon’s DAX5 warehouse in the City of Industry, California. She loads up her van with packages for over 200 homes, many of them mansions in the hills of West Covina with steep steps and long driveways. But on the morning of December 19, Valdez didn’t head to her blue Amazon van as usual. Instead, she parked her personal vehicle a few blocks down from the warehouse, where a growing coterie of her coworkers were gathering. They handed out signs reading “Amazon ULP Strike” and fixed pins to their blue vests. Cameras from nine different news stations were waiting for them down the block. “It was beautiful chaos,” Valdez told me. Hundreds of workers marched down the street to the driveway where their colleagues were loading their vans for the day, chanting, “Union busting is disgusting!” and “When Teamsters fight, Teamsters win!”

Valdez and her colleagues were among Amazon workers at warehouses all over the country who recently unionized with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and went on strike the week before Christmas over the company’s refusal to bargain with or even recognize their union. Union representatives say that 10,000 Amazon workers have unionized with the Teamsters at facilities in New York, Illinois, California, and Georgia. But despite the growing number of employees joining the union, the company has refused to bargain with workers at any of these facilities, including JFK8 in Staten Island, the first Amazon warehouse to unionize.

After the Teamsters gave Amazon a bargaining deadline of December 15, drivers and warehouse workers voted to authorize strikes across DFX4, DAX5, KSBD, and DAX8 in Southern California; DCK6 in San Francisco; DGT8 in Atlanta, Georgia; DIL7 in Skokie, Illinois; and JFK8 and DBK4 in New York City. When that deadline passed without a response from the company, workers ended up striking at nine warehouses, and established picket lines at more than 200 Amazon facilities, resulting in the biggest strike against the company in history. For days in freezing temperatures, strikers interrupted business as usual and spent their time talking to drivers for Amazon’s contracted delivery service partners (DSPs) who have not yet unionized, generating national headlines and building numbers simply too big for management to ignore.

While that group must still grow much larger before it can substantially impact Amazon’s expedient functions or bottom line, the December strike was a particularly significant escalation in light of a Trump administration ushering in a new anti-worker regime. Within the first weeks of his presidency, Trump fired National Labor Relations Board member Gwynne Wilcox for “unduly disfavoring” employers, and the board is expected to roll back Biden-era labor protections once Trump installs new pro-employer members.

But regardless of these forthcoming changes, Amazon workers see this as only the start of their shop-floor movement. “We’re gathering numbers, going to different warehouses, building committees, getting strong leaders, and helping it spread,” Valdez told me. “Seeing so many workers are hungry for it is what makes me want to keep being an organizer.”

Justin Peterson, a driver at Amazon’s DGT8 facility outside of Atlanta, Georgia, didn’t know much about the benefits of unionizing when another driver started talking to him about it at work. His father-in-law, a USPS driver, encouraged him to get involved: “He told me everything about all the good things and why every job needs a union and exactly what they do for people.” Drivers get little time with each other before heading out for the day, so Peterson had to get creative to find time to talk to his coworkers about joining the union. He brought it up as they were loading their trucks or called them on the phone on their routes. After Peterson decided to join and wrangle his coworkers as well, he found that the most effective message to get people on board was “just saying the facts.” “I’m a driver just like you,” he said. “I know you’re tired of this.” In November 2024, Peterson and his coworkers formed a union with the Teamsters, and a month later, they voted unanimously to authorize a strike.

A top issue for the drivers who went on strike across cities in December is a massive workload, which is established by an algorithm that workers say pushes and inaccurately assumes their physical limits. Valdez says that when she first started driving for Amazon five years ago, her routes were manageable. But since then, “routes just kept on getting bigger, stop counts [got] bigger, package counts [got] higher.” Now she delivers to nearly 250 locations a day and often skips her breaks to complete her routes on time to avoid being disciplined or taken off the schedule. “If you can’t do it, then that’s going to go on your record that you’re being too slow,” she said. “And I need to keep my job.”

Drivers and warehouse workers are also seeking better pay and benefits. Before Amazon announced a $1.50 raise for all fulfillment and transportation associates in September 2024, drivers at Peterson’s warehouse in Georgia were making $19.75 an hour, while their fellow Teamsters driving for UPS were making significantly more, in some places as high as $45 an hour. “We deserve at least $30 an hour,” Peterson told me. Drivers are also asking for more time off and to be paid for the holidays when the warehouse shuts down. Peterson said that paid time off currently accrues at just 1.7 hours a week, meaning drivers have to work six weeks to be able to take a single day off.

Lamont Hopewell, a driver at Amazon’s DBK4 warehouse in Queens, New York, was part of the majority of workers at the facility to authorize a strike on December 19. When he showed up at the picket line that morning, a large crowd of workers and community supporters had already gathered. “Everything we’ve been working toward for these past few months, it all came to fruition,” he said. “What we said we were going to do, we did. And we did it in an organized way, in a legal way.” Still, Amazon deployed its familiar anti-union playbook, relying on police and security measures to intimidate workers. On the first day of the strike at DBK4, managers called the police and the NYPD arrested a Teamsters organizer and a rank-and-file driver who was trying to join the picket line. The Teamsters also requested an investigation by the New York City Law Department after a pipe on the outside of the warehouse unleashed icy water on the tables union leaders set up, which propped up shirts, heaters, and food supplies. Hopewell said he believed Amazon managers had opened the pipe. “It was crazy to think that Amazon would be doing that instead of actually coming to the table like the trillion-dollar company they are and negotiating with us for fair things that we’re asking for,” said Hopewell.

At Valdez’s warehouse in California, Amazon juiced security in response to the strike, and tried to change workers’ schedules to nullify its effects. On the second day of picketing, the company erected a fence around the whole facility and some DSPs moved schedules for their drivers to early in the morning in order to avoid the picket line, she says. For the rest of the six-day strike, Valdez and her coworkers showed up at 4 am to talk to as many drivers as possible.

In December, Amazon called the strikes “illegal” and to this day maintains that it is not the employer of its drivers, who work for DSPs, the small companies that Amazon contracts for its delivery services. But many DSPs exist solely to service Amazon, and the company still dictates drivers’ attire, schedules, and routes. Workers have fought that argument in court, and in October of 2024, an NLRB administrative judge ruled that Amazon was a joint employer of its drivers, meaning its DSP excuse no longer holds.

While the nationwide strikes had a limited impact on Amazon’s overall business operations, workers say they saw firsthand how their picket impeded typical operations. Valdez says she and other picketers delayed each wave of drivers by 15 to 20 minutes, and that DSP managers had to pick up routes for the day. At Hopewell’s station, another driver told him that packages had been diverted to a different delivery station.

Since the big strike in December, unionized workers have continued to assert their presence at work and secure wins through collective organizing. When DGT8 shut down during a recent storm, Peterson’s was the only DSP to be paid for the full 10-hour workday. “All because we stood up to our boss,” he said. The Teamsters also secured a win in court in early February, when an NLRB administrative law judge ruled that Amazon had illegally enforced its time-off policy to punish workers for participating in walkouts and strikes. “This ruling sends a clear message: Amazon workers have every right to walk off the job to demand better pay, safer conditions, and a union contract, and they will keep fighting,” said Teamsters general president Sean O’Brien in a statement.

Workers hope that the power they demonstrated at their warehouses will inspire others to organize. Randy Korgan, the Teamsters’ national director for Amazon, said they’ve gotten “thousands” of organizing leads from the actions. “You have many, many more units that are looking to do the same thing and exercise their power as well,” he said.

The movement is building momentum at a time when Trump is rolling back some of the legal protections afforded by the NLRB under Biden that supported new organizing at Amazon and beyond, meaning employers may be less likely to face penalties for violating workers’ rights to organize. On February 17, Acting NLRB General Counsel William Cowen issued a series of memos indicating that he disagrees with Biden-era rulings, including the ban on captive audience meetings and the board’s decision in Cemex, which required employers to recognize and bargain with a union if a majority of workers request the union, and the company has broken certain labor laws. Celine McNicholas, director of policy at the Economic Policy Institute, said overturning these decisions could further embolden employers like Amazon to break the law. “It’s an open invitation to suppress workers’ right to a union,” she said.

But for now, the NLRB is unable to take up these or any other issues, since Trump fired board member Gwynne Wilcox and left them without a quorum. Workers can still file unfair labor practice charges and have those cases evaluated by an administrative law judge, but if employers or workers want to appeal the ruling, the NLRB cannot issue a decision, leaving cases in indefinite limbo. Last year, Elon Musk’s SpaceX brought a case to federal court challenging the constitutionality of the NLRB itself, seeking to strip the agency of its authority. “In the first two weeks of the Trump administration, they’ve essentially gotten a win because the effect is the same,” said McNicholas. “Either the board is deemed unconstitutional or it just doesn’t have the same quorum it needs to function. The experience of working people is the same.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In his e-mail firing Wilcox, Deputy Director of Presidential Personnel Trent Morse wrote that she was being terminated for “unduly disfavoring the interests of employers.” Even if Trump does appoint a new board member, “We now know that a prerequisite to serve on the National Labor Relations Board is that you will not rule a certain way against employers,” said McNicholas. “And that is catastrophic for workers’ rights.”

Without an operational NLRB, Amazon will likely try to continue delaying negotiations with the union, but workers can still take action on the shop floor to force the company to the bargaining table. Regardless of the Trump administration’s recent actions, workers still have the right to unionize, engage in collective bargaining, and take collective action to improve their working conditions. “Even under the Biden board, workers needed to be prepared to take action in order to win strong contracts,” said Dr. Rebecca Givan, a professor of labor studies at Rutgers University, in an e-mail. “We can expect militant action to look as it always has: Some workers will organize to disrupt business as usual and withdraw their labor.” Because labor law is already stacked to favor employers, McNicholas says, workers have long known that their bargaining power comes from shop-floor organization. “To the extent that there’s momentum out there…I don’t think that has anything to do, frankly, with the existing law,” she said. “It’s workers that win unions, not an NLRB process.”

The stakes to improve working conditions at Amazon are too high for workers to sit out the next four years. “No matter who’s in office, no matter what the administration is, the most important thing is that the power is in the people,” said Hopewell. “I don’t care how much money your company makes. The fact is that they wouldn’t be able to make it without us. So at the end of the day, we just need to stick together and keep it moving no matter who’s in office.”

More from The Nation

Welcome to the New Military-Industrial Complex Welcome to the New Military-Industrial Complex

An assortment of new firms, born in Silicon Valley or incorporating its disruptive ethos, have begun to challenge the older ones for access to lucrative Pentagon awards.

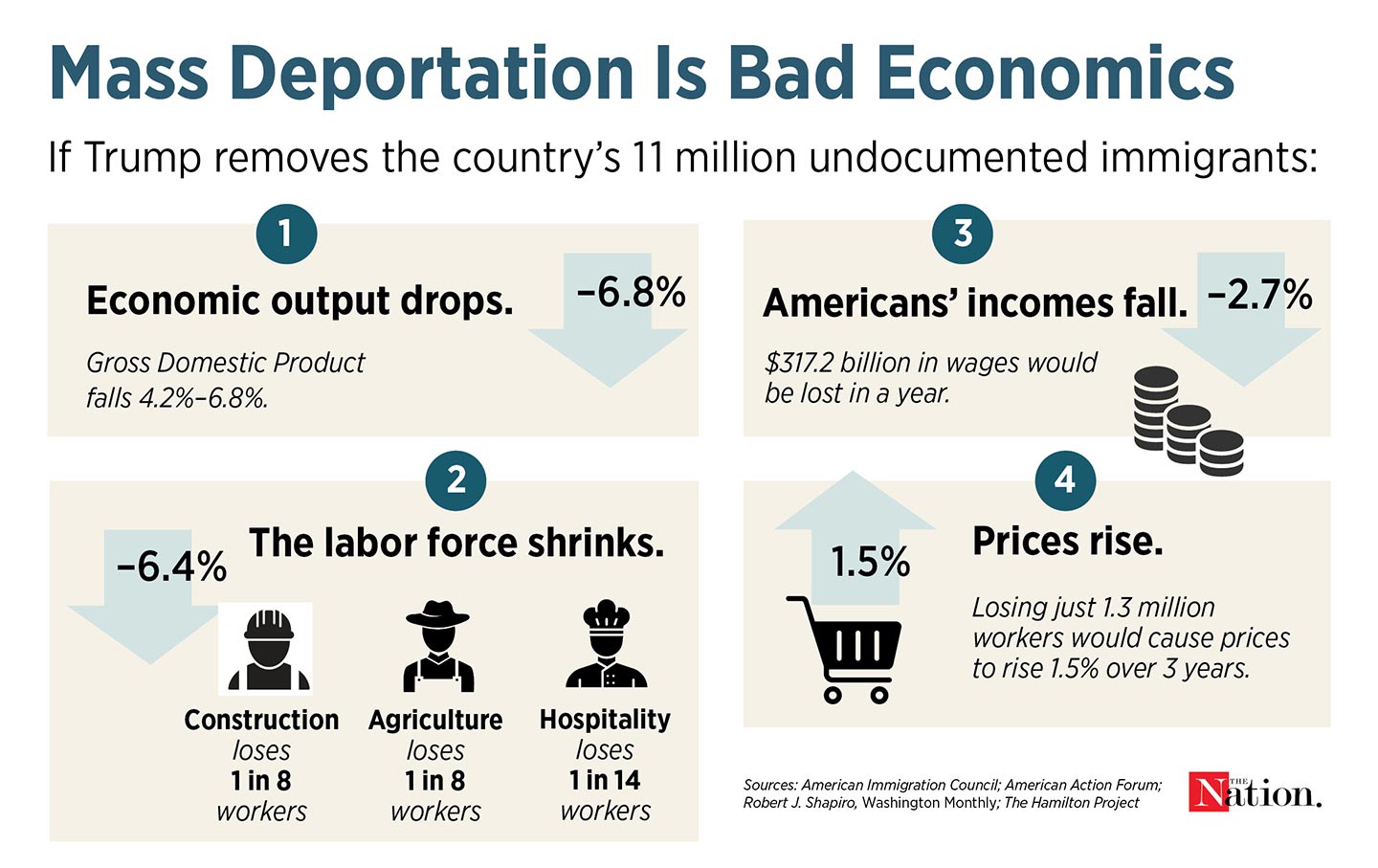

Mass Deportations Aren’t Just Evil. They’re Also Terrible Economics. Mass Deportations Aren’t Just Evil. They’re Also Terrible Economics.

Immigrants don’t steal citizens’ jobs and wages. They grow the economy for all.

Why Elon Musk and the GOP Have the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau in Their Crosshairs Why Elon Musk and the GOP Have the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau in Their Crosshairs

Republicans have long wanted to kill the CFPB. With Musk and Russell Vought, they may finally have their chance.

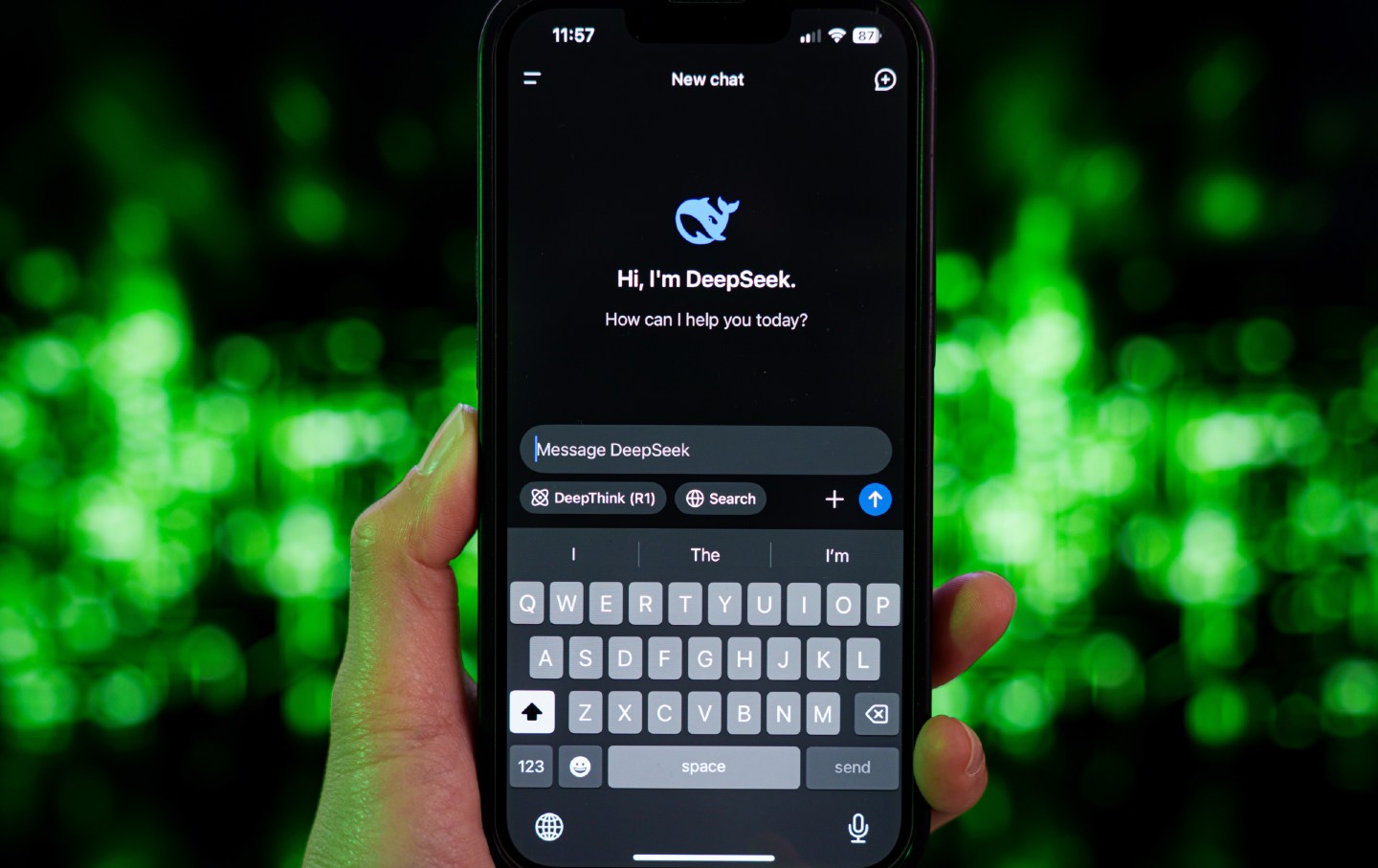

Why DeepSeek’s Surprise Breakthrough Shouldn’t Have Come as a Surprise Why DeepSeek’s Surprise Breakthrough Shouldn’t Have Come as a Surprise

While America was busy with stock buybacks and quarterly profits, China spent decades building an integrated system linking research, manufacturing, and innovation.

Donald Trump’s Retrograde Worship Will Tank America’s Auto Industry Donald Trump’s Retrograde Worship Will Tank America’s Auto Industry

Trump's tariffs will protect the US auto industry just long enough for it to decline into technological obsolescence.

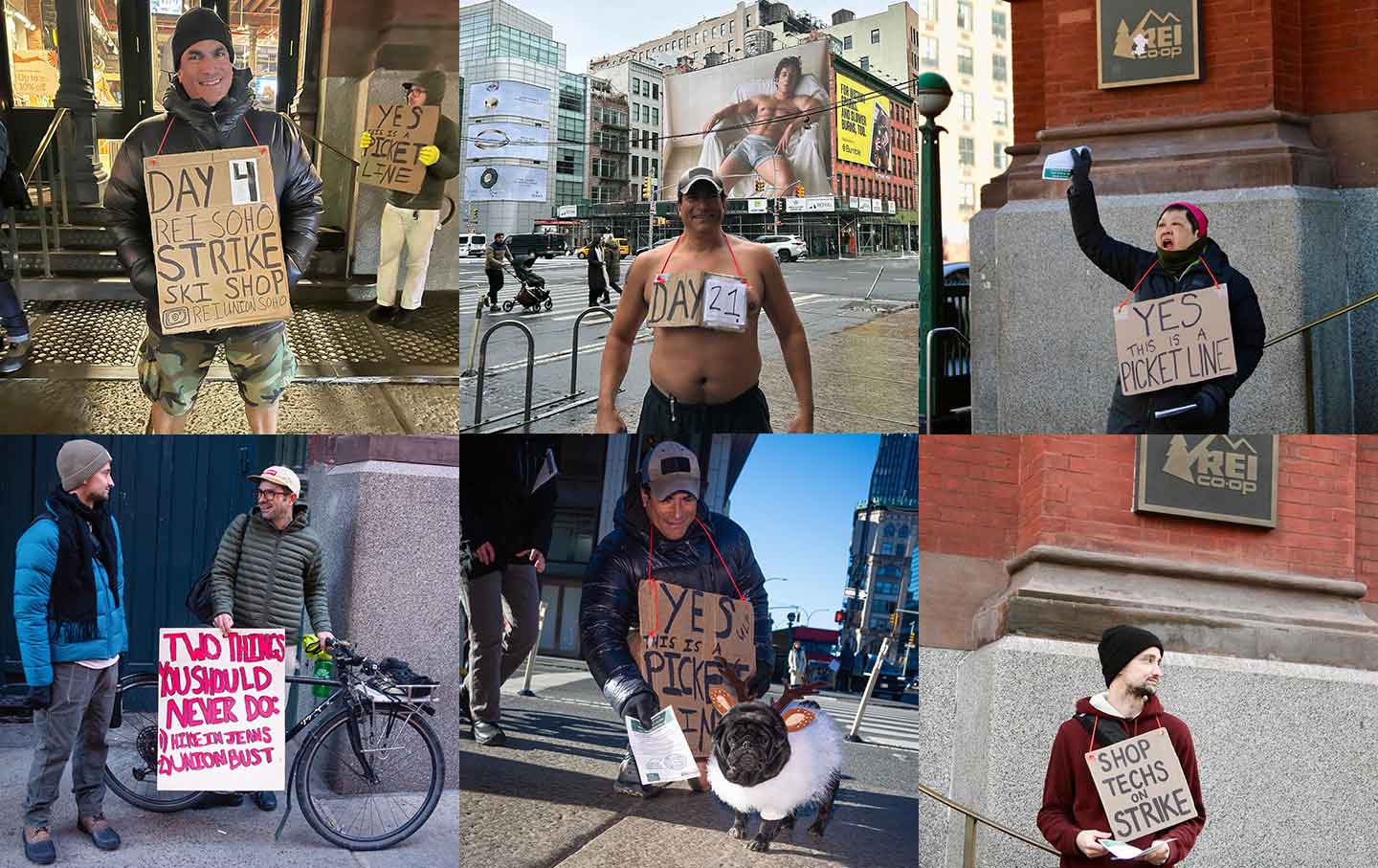

REI Sells the Great Outdoors While Workers Breathe Chemicals in a Windowless Basement REI Sells the Great Outdoors While Workers Breathe Chemicals in a Windowless Basement

Ski shop workers at an REI in New York City went on strike after the company took away their respirators.