Are Men OK?

According to Richard V. Reeves, American society is failing to address the needs of men and boys. Are his solutions the flip side of feminism—or just another form of backlash?

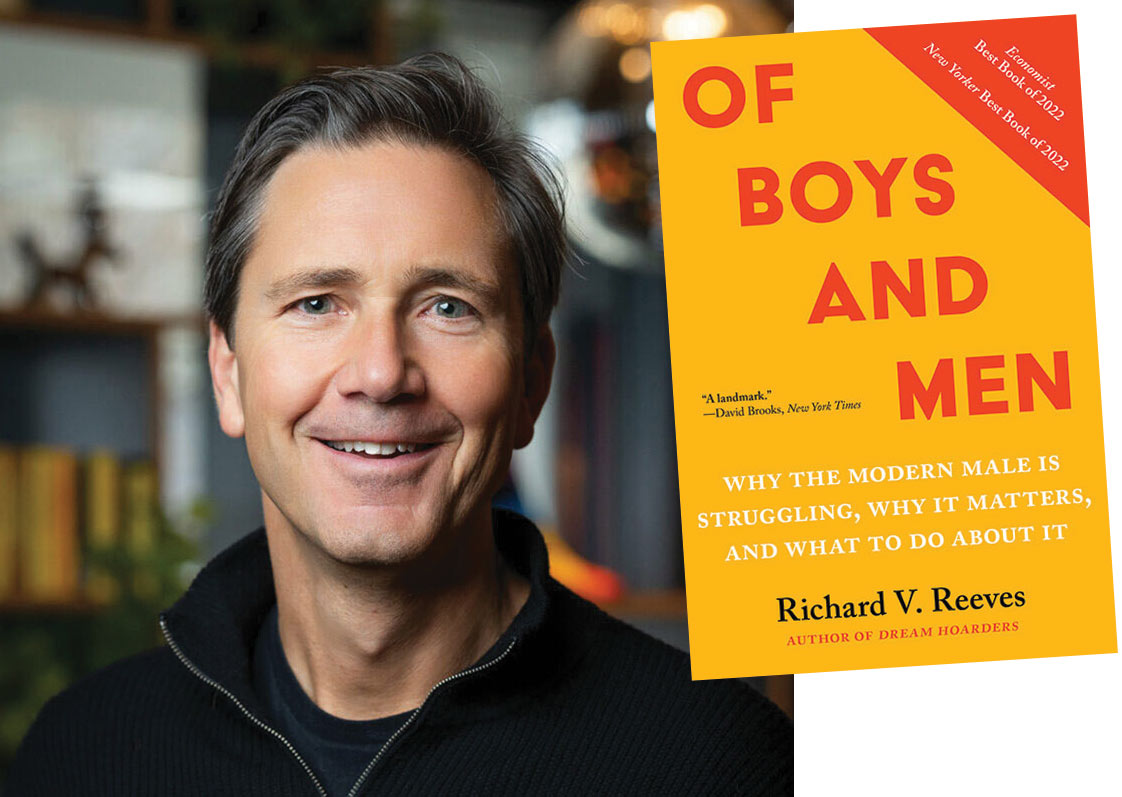

On November 21, 2024, Richard V. Reeves stood in a greenroom at The Washington Post’s third annual Global Women’s Summit. Reeves, the president of the American Institute for Boys and Men (AIBM), was the only man in a lineup that included former Democratic Party House leader Nancy Pelosi, historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, and actress Kerry Washington. Leaning against a wall, he made small talk with his copanelist Grace Bastidas, the editor in chief of Parents.com. The target audience for his 2022 book, Of Boys and Men: Why the Modern Male Is Struggling, Why It Matters, and What to Do About It, Reeves told her, is a liberal mom worried about her son.

At one point, Reeves himself would have been skeptical of his book’s premise. He’s described feminism as perhaps “the greatest economic liberation in human history.” But in his work studying economic inequality at the Brookings Institution, where he was formerly a senior fellow, he had run into what he has called the “side effects” of feminism’s “glorious achievements.” The starkest data was in education, particularly in college. Since Title IX was passed in 1972, the gender gap in bachelor’s degrees has widened, but in the opposite direction. The biggest risk factor for dropping out of college, controlling for everything else, is being a man. Those struggles have extended to the labor market. When adjusted for inflation, most American men today earn around $3,000 less than men did in 1979, which leads to a grim realization: Much of the narrowing of the persistent wage gap between men and women can be explained by the stagnating wages for men.

Today, Reeves notes, women between the ages of 25 and 34 are entering the workforce at greater rates than they ever have, while the workforce participation of men in the same age cohort hasn’t grown in a decade. Fatherhood has also been destabilized: More than one in four fathers with children 18 or younger now live apart from their children. There is more bad news in men’s health, both physical and mental; men fall victim to alcohol or drug overdose or suicide—so-called deaths of despair—at a rate three times higher than that of women. The suicide rate for men between 25 and 34 has gone up by nearly a third since 2010. In its 2023 “State of American Men” report, the Equimundo Center for Masculinities and Social Justice noted that almost half of the men it surveyed had thoughts of suicide in the previous two weeks.

When Reeves set out to write a book on these findings, friends and colleagues advised him to drop it as a matter of career preservation. “What you’re saying is true,” Reeves remembers hearing. “But for God’s sake, don’t say it.” They warned that he’d end up sounding like Josh Hawley, the Republican senator from Missouri whose 2023 book Manhood: The Masculine Virtues America Needs advances the issue from the right. Hawley represents the post-Trump, post–Me Too Republican Party’s awkward attempt to synthesize its church-based brand of social conservatism with the “manosphere,” a collection of online subcultures unified by anti-feminism. Another product of this collaboration is Vice President JD Vance, whose choice phrases like “childless cat ladies” were ripped from the manosphere podcasts he’d appeared on as he was burnishing his credentials within the extremely online New Right.

Reeves felt a responsibility to take on the men question, because he thought ceding this ground to the manosphere and the New Right was wrongheaded. But he shared his doubters’ reservations. The achievements of second-wave feminism—the Equal Pay Act, Title IX, and Roe v. Wade—had been won within living memory. In an era shaped by the grievances of conservative men, those victories have proved tenuous. Writing a book about the plight of American men seemed self-pitying at best and reactionary at worst. But Reeves noticed that even when people tried to dissuade him, they’d share concerns about the state of the men in their lives. And it’s well within the feminist tradition to analyze the state of men. So Reeves set to work, assembling a manuscript bursting with data on how men and boys were falling behind. He lambasted denialism from the left and atavism from the right. Then it was rejected by every publisher he sent it to.

Reeves recalibrated. He’d need to be less polemical, lest he come off as a watered-down men’s rights activist. He also didn’t think his message would travel if he branded himself as an ally of feminism promoting healthy masculinity, even though that wouldn’t necessarily be an incorrect way to describe him. He struck the right balance, and in 2022 Brookings published Of Boys and Men on its own press. Almost three years later, the project Reeves was told would ruin his career has done the opposite: It launched the mild-mannered British policy wonk into public intellectual stardom. If you’ve read a magazine article, watched a TV news segment, or listened to a podcast on the “crisis of masculinity” lately, you’ve encountered an interview with or at least a reference to Reeves. His book was on Barack Obama’s summer reading list, and the philanthropist Melinda French Gates awarded Reeves a $20 million grant—$5 million for AIBM and $15 million in a donor-advised fund to give away. In the spirit of his vision of gender equality, Reeves named the fund Rise Together.

Reeves’s critics, however, remain skeptical. They argue that his focus on men reproduces the very zero-sum thinking on gender equality he seeks to transcend, and that despite noble intentions, by elevating the idea that men are falling behind women—an idea that most women, who on average earn nearly 20 percent less than men, would certainly find dubious—he will further inflame the backlash he wants to contain.

Though Reeves told me that his wife describes him as a “thin-skinned polemicist,” he seems to welcome the skepticism. His appearance at an event like the Global Women’s Summit, just two weeks after Donald Trump defeated Kamala Harris in the US presidential election, would be an opportunity to put his message—and his ability to convey it—to the test.

As Reeves was whisked away for makeup, I chatted with another panelist, Emily Oster, an economics professor at Brown focused on child-rearing, who became both a star and a lightning rod by pushing for school reopenings during the pandemic. Oster recently launched a parenting podcast on Bari Weiss’s right-leaning media outlet The Free Press, making her no stranger to offending liberals and leftists. Still, Oster had trouble initially accepting Reeves’s premise. “Oh, men are struggling? It’s harder for some of us to get our head around it,” she said. “Because, at the top, it’s just a bunch of penises.” Men make up nearly three-quarters of the federal legislature and two-thirds of state legislatures. The billionaire and Fortune 500 CEO class remains an almost exclusively male domain. If you’re a woman navigating an elite professional milieu, as a generous slice of the attendees of this Goldman Sachs–sponsored summit were, you might wonder what the hell Reeves is talking about. But Reeves never hesitates to point out that he is chiefly concerned with men at the bottom of the economic and racial hierarchy. “There are still places for women to go at the top, but there are parts of the distribution where men are really struggling,” Oster said. “Richard has moved me on this a lot.”

Reeves, Oster, and Bastidas took the stage in a standing-room-only auditorium for their panel, titled “Parenting 3.0.” I stood near the back at a high-top table next to Oster’s assistant. The panel’s moderator, the journalist Sally Quinn, asked Bastidas about the concept of the “mommune”—a group of single mothers who raise their kids together under one roof. Bastidas explained that the nuclear family is not the norm in most of the world and shouldn’t be in the United States, either. “Some of us have plans with our best girlfriends—like ‘OK, when our husbands have gone wherever they need to go, we will move in together,’” Bastidas said. The audience broke into laughter. Reeves raised his eyebrows. “I knew this was going to be brutal,” he muttered into his microphone, to more laughter. Quinn asked Reeves the next question, about the role of fathers. As he spoke, he turned to his right and addressed Bastidas: “Where are we going, by the way? When you say ‘the fathers,’ is there something you want to tell me?”

“The big disco in the sky,” Bastidas responded. The audience continued to laugh.

“It takes a village—I agree. Families come in all shapes and sizes—I agree. But some of the villagers should be men,” Reeves said. He explained that dads used to matter mostly because they were the breadwinners, and that’s changed, for a good reason. But “dads still matter, and we need to find policies and a culture and a way of talking about this that doesn’t somehow see them as second-class parents who are somehow less important,” he continued. “We have to have a conversation about masculinity in a positive way. I understand it’s a difficult time to make that argument. But honestly, you cannot ignore these issues. You cannot ignore these questions and then wonder why the people who are not ignoring them are getting all the attention.”

The panel ended shortly after Reeves’s monologue. As the lights came up, Oster’s assistant turned to me and said, “Have you ever met someone who was so good at communicating?”

Ifirst met Reeves the day before the Global Women’s Summit, at a coffee shop near the Brookings offices in Washington, DC. Reeves, 55, is tall and wiry, with a swoop of brown hair graying around the edges. He was dressed in business casual and would occasionally slip his glasses on when he wanted to quote a statistic from his phone or laptop. He was quick to crack a joke but would also pause and lean back against the wall for several beats, eyes closed and lips pursed as he considered a question.

Two weeks after Election Day, I wanted to learn why a man who has described himself as “proudly boring” had become the go-to expert on American manhood and a Cassandra to Democrats reeling from a campaign season that saw male revanchism coincide with an exodus of young men from the party. “People aren’t worried about the first thing I say, whether it’s the gaps in education or the suicide rate,” Reeves said as he sipped his coffee. “They’re worried about the fifth thing. They have a question in the back of their mind: ‘Where is he going with this?’ And that’s a reasonable thing to be thinking!”

That captures what Jill Filipovic, the author of The H-Spot: The Feminist Pursuit of Happiness, first thought when she encountered Of Boys and Men. “For a lot of feminists, it raises our spidey senses when we see someone who’s arguing ‘but men and boys too,’” she said. “It’s like the ‘All Lives Matter’ of the feminist movement.” But she was pleasantly surprised. “He may not approach it the same way that I do, but he is not someone who’s trying to take something away from feminism,” Filipovic concluded.

“Feminism has upended patriarchy, a specific social order that had the fatal flaw of being grossly unequal,” Reeves writes in his book. He doesn’t think that feminism has gone too far—he thinks it hasn’t gone far enough. “Women’s lives have been recast. Men’s lives have not,” he writes. What is needed is a “positive vision of masculinity for a postfeminist world.” Of Boys and Men is a pop social science book with pithy aphorisms, plenty of charts, and several signature policy proposals. For example: to address their struggles in education, hold all boys back a year and invest in more technical schools. Start initiatives to encourage men to join the female-dominated HEAL professions (healthcare, education, administration, literacy), mirroring the efforts to get women into STEM. To help dislocated dads, institute six months of fully paid parental leave.

Reeves’s role during the early days of AIBM, which he envisions becoming a DC policy shop, has been that of communicator. He or his writings have appeared in just about every outlet you’ve heard of and many you haven’t. The idea behind the media blitz, Reeves told me, is to create a “permission space” in the mainstream and among liberals to talk about men’s struggles in a way that’s consistent with women’s equality. “It didn’t really seem like anyone had the stomach to take it on and champion it as an issue,” said Christine Emba, a staff writer at The Atlantic who wrote a viral article on the state of American men in 2023, when she was a columnist at The Washington Post. Emba interviewed Reeves for her story, and he later asked her to join the board at AIBM. Emba herself felt the need for that permission space in liberal newsrooms. “There’d be a groan,” she recalled, “and people would say, ‘So you hate feminism? So you hate women?’”

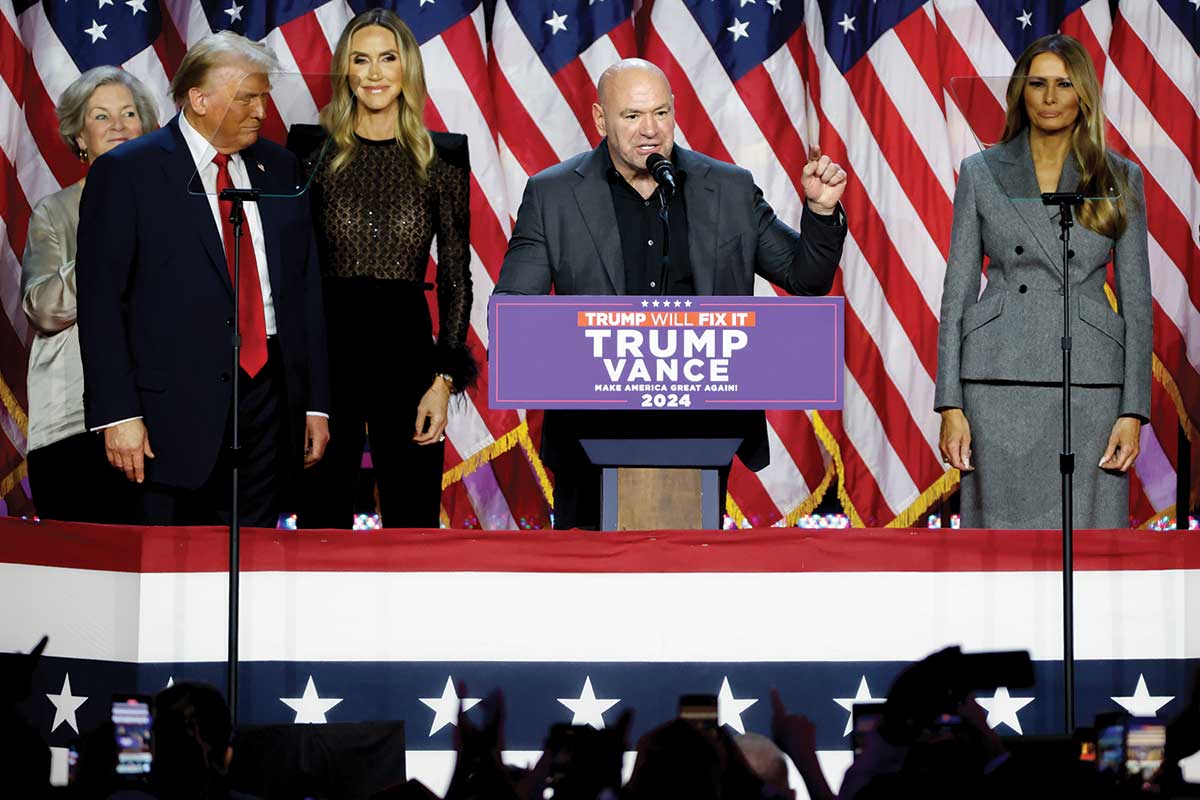

“If you are a man in this country and you don’t vote for Donald Trump, you’re not a man,” the 31-year-old conservative media star Charlie Kirk said last July as he led the Trump campaign’s effort on college campuses. In 2024, Trump enlisted his sons as strategists, and he was introduced at the Republican National Convention by Ultimate Fighting Championship CEO Dana White. (Reeves pointed out that in 2016 and 2020, Trump was introduced at the RNC by his daughter Ivanka.) On election night, White thanked a list of podcasters who were part of a new media strategy reportedly masterminded by an 18-year-old named Bo Loudon, a friend of Barron Trump whose parents are Mar-a-Lago members. This strategy appears to have paid dividends: In 2020, 56 percent of men under 30 voted for Joe Biden. In 2024, 56 percent of that cohort voted for Trump—a nearly 15-point swing to the right, according to the AP Votecast Survey. “Democrats should be fighting for every constituency. And this is one that we’ve really left on the table for a long time,” said Shauna Daly, a longtime Democratic campaign leader who credits Reeves for inspiring her new project, called the Young Men Research Initiative.

As the election results brought young men’s drift away from the Democrats into mainstream view, the media needed someone to explain why. Reeves, who is a member of neither major party, became an in-demand source, and his diagnosis has been blunt. “What we had was performative masculinity from the right and deafening silence from the left: Democrats couldn’t expose the lack of substance on the Republican side, because they wouldn’t even acknowledge that there were problems that needed solving,” he told The Washingtonian in a postelection interview.

In an interview with The Guardian, Reeves said that since men delivered for Trump, “Trump now needs to deliver for men.” I asked him what that would look like and how he’d engage with the White House. The worst scenario, he said, would be “if the Republicans pick up some of this pro-male policy and support it, but in a very anti-feminist, anti-woman way. That they use it to poke women in the eye.” But if the Republicans are interested in an Office of Men’s Health, or investments in apprenticeships and technical schools, or a plan to increase the number of male school teachers, Reeves says he will be there with his white papers.

In these polarized times, Reeves has his share of critics across the spectrum. On the right, he’s portrayed as inauthentic and untrustworthy because he doesn’t endorse a wholesale restoration of traditional gender roles. “His remedies are deeply unappealing,” wrote the young conservatives Evan Myers and Howe Whitman III in American Compass, because he wants men to become “junior partners in a world increasingly shaped by women’s sensibilities.”

Criticism on the left is more measured. There is an uneasiness with Reeves’s popularizing the idea of the beleaguered man in a climate of rising anti-feminism. “I worry that some of his rhetoric is inadvertently perpetuating a culture of woman-blame that we have in the US, in terms of fueling this perception that if men are struggling in our society, it’s because of our society’s efforts to support women and girls at their expense,” said Jessica Calarco, a professor of sociology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the author of Holding It Together: How Women Became America’s Safety Net.

For Reeves, the issue hits close to home. Part of the journey began with his sons, who are now in their 20s. As teens, they’d taken to Jordan Peterson, the Canadian psychologist who spoke empathetically to young men while railing against feminism. Reeves interpreted this partly as a rebellion against the liberal dogma they had absorbed in their upper-middle-class home and school in Bethesda, Maryland. While Reeves “disagreed strongly” with a lot of what Peterson said, he couldn’t help but think that the connection between Peterson and his audience revealed “a gigantic reservoir of unmet human need.”

I told Reeves that his description of Peterson as a “genuine intellectual wrestling with real issues” made me scoff when I read it. In response, Reeves lamented that Peterson has since gone off the rails, but he explained that the passage was part of a broader strategy of triangulation. There are parts of his book that trigger the same reaction from conservatives. “Part of the challenge is, do you equalize the scoffing?” he said.

As Reeves was finishing the book, his sons told him he needed to look into Andrew Tate, the brawny misogynist influencer with a Bond-villain aesthetic currently under investigation for rape and human trafficking, who peddles a cruel brand of male self-help. Around the time Reeves’s book was published, Tate became a worldwide superstar. Reeves was often asked to explain the appeal of Tate, Peterson, and a growing roster of copycats who were taking the message of the once-fringe manosphere to millions. His attempts to grapple with the question solidified a tenet of Reeves’s thought: Look at the demand, not the supply. “The failure of mainstream institutions…to acknowledge and tackle the real problems facing many boys and men has created a vacuum in our politics and in our culture,” he wrote in 2022.

One of Reeves’s forerunners is the Atlantic senior editor Hanna Rosin, whose 2012 book The End of Men: And the Rise of Women covered similar ground. “I was completely right and completely wrong at the same,” Rosin told me. She was right about how disaffected men could wreak havoc on American politics, but she was naïve to think that somehow women would escape that backlash. “If you look around at the landscape now—yes, technically, men are suffering,” she said. “But women are being crushed and dragged back 50 years.”

Reeves was born on July 4, 1969, in the city of Peterborough, 70 miles north of London. His mother was a part-time nurse originally from Wales, who sent him to ballroom dancing classes on Saturdays. His father worked as a manager at companies that sold kettles and washing machines. “My dad was a bit of a class warrior,” Reeves told me. “He hated the aristocracy and the monarchy and any sense of hereditary privilege.” After a stint working for outlets like The Guardian, Reeves joined Prime Minister Tony Blair’s “New Labour” government in 1997 and became a true believer in Third Way ideology. Personified by Blair in the UK and Bill Clinton in the US, it was an attempt to synthesize the social democratic currents of the Labour and Democratic parties and the neoliberalism of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Reeves worked for a year in the Blair administration before going on to get a PhD in philosophy, for which he wrote a well-received biography in 2007 of the 19th-century British philosopher John Stuart Mill, a towering figure of liberalism. An early supporter of women’s emancipation, Mill is Reeves’s intellectual lodestar.

Partly as a result of his study of Mill, Reeves joined the Liberal Democratic Party. The height of his political career in England came in 2010, when the Lib Dems and David Cameron’s Tory Party unexpectedly formed a coalition government. Reeves was named director of strategy under Deputy Prime Minister and Lib Dem leader Nick Clegg. During Reeves’s tenure, his support cratered, partly because of a betrayed campaign promise to abolish college tuition fees. “It was stupid; I was a bloody idiot,” Reeves said in 2012 after he stepped down from his post.

The end of Reeves’s career in British politics was a perfect time for a fresh start. He moved to the United States, where he was soon hired by Brookings to study economic inequality. He’d left England partly because he found the class structure stultifying, but he quickly realized, he said, that the relative lack of class consciousness in America meant that “the rich people here are just colossal jerks” who rigged the system for their benefit, then absolved themselves by “putting the right sign in their front yard and voting the right way.” His frustration with this class myopia led him in 2017 to write Dream Hoarders: How the American Upper Middle Class Is Leaving Everyone Else in the Dust, Why That Is a Problem, and What to Do About It. In the wake of Trump’s ascension to the White House, here was a polemic indicting a cloistered elite embodied by a Democratic Party that had just suffered a crushing defeat propelled by the hinterlands. That year, Politico named Reeves one of the most important thinkers in the country “for explaining America’s class warfare.” Dream Hoarders sowed the seeds of Reeves’s next project. “The gendered nature of inequality just kept popping up,” he said.

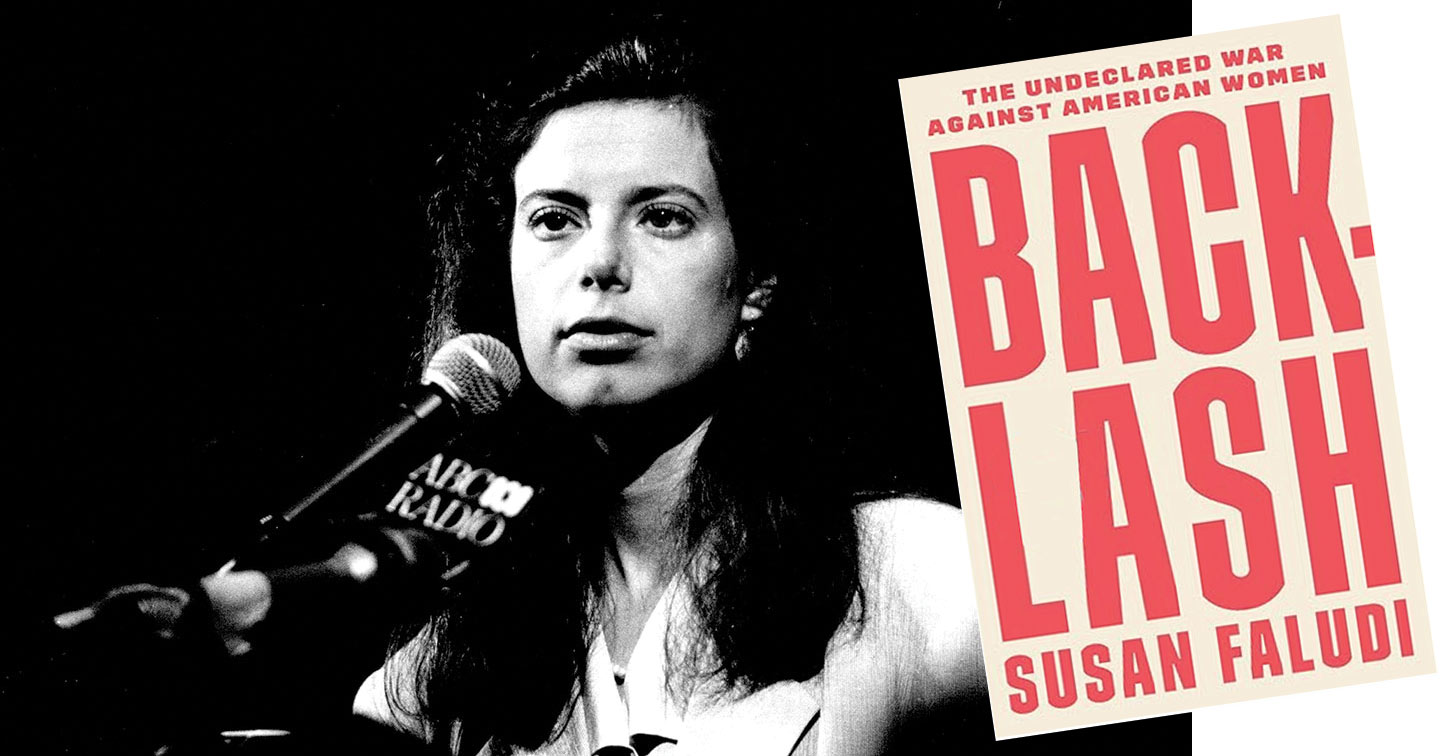

In writing Of Boys and Men, Reeves was partly following in the footsteps of the feminist writer Susan Faludi, whose 1999 book Stiffed: The Betrayal of the American Man, the follow-up to her 1991 Pulitzer-winning Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women, argued that as the New Deal order withered away, so too did a model of manhood that “showed men how to be part of a larger social system,” one defined by traits like loyalty and service. Even before that, a study of heroic male archetypes from the 1700s by the historian E. Anthony Rotundo found that “public usefulness” was among the most valued traits—a man of the people, rather than the lone ranger traversing the frontier or the lonely gamer traversing Twitch streams. In his book, Reeves cited a study by Australian researchers who examined the words that men who have attempted suicide used the most often to describe themselves. “Useless” was at the top of the list.

By the end of the 20th century, American culture had “left men with little other territory on which to prove themselves besides vanity,” Faludi wrote. She called the form of masculinity that emerged to fill this vacuum “ornamental,” based in celebrity and mass consumerism, where manhood was “a performance game to be won in the marketplace, not the workplace, and that male anger was now part of the show.” Though MAGA conjures a hazy nostalgia and aims to turn back the clock on social progress, Faludi has written that it is essential to understand Trump’s brand of manliness—vain, image-obsessed, devoid of “old-school values” like integrity, honor, and honesty—not as a relic of the past but as thoroughly modern: the apotheosis of the ornamental.

The simplest story to explain what ails working-class men today is that of the decimation of America’s industrial workforce. The Fordist wage—which enabled a single (male) worker to support a family—withered away at the same time that a new generation of women entered into higher education and the workforce. As men lost the ability to become breadwinners en masse, the story goes, the breadwinner role lost its relevance, and then men lost themselves. These changes hit Black men especially hard, because manufacturing jobs were much more likely to be their gateway to the middle class. The loss of stable employment and the simultaneous rise of the prison system combined to alienate Black men from family life and to create the racist stereotype of the “deadbeat dad.” Before “toxic masculinity” became a ubiquitous term to describe rich, powerful white men like Donald Trump, it was attached to out-of-work Black men.

While Reeves described Dream Hoarders as a “poke in the eye” to wealthy liberals, it was also a cheeky provocation aimed at the Occupy Wall Street and Bernie Sanders generation. Instead of targeting billionaires, Reeves pointed the finger at the upper middle class. For Calarco, the sociology professor, Reeves’s failure to indict the economic ruling class in Dream Hoarders is a weakness that extends to his writing about gender. “If men are struggling, it’s because billionaires and big corporations and their cronies have really forced us all to take care of ourselves without the kind of social safety net that other high-income countries are able to take for granted,” she said.

As a nominally nonpartisan wonk trying to build consensus on a hot-button issue while causing minimal offense, Reeves is not in the business of naming the names of those preventing human flourishing. But many working-class men are angry, and they need a story about why their life sucks. The right can provide a list of scapegoats: liberal elites, DEI administrators, Marxist professors, women. “The male malaise is not the result of a mass psychological breakdown, but of deep structural challenges,” Reeves writes in Of Boys and Men. There are no villains in this story, which leaves the field open for the right to assign blame.

“If not women, then who?” Calarco asks. “Without actually telling people who’s really to blame, it’s very easy for people to dismiss that disclaimer and even assume that Reeves himself might not believe it if he’s not willing to point the finger somewhere else instead.”

In recent years, Reeves has questioned some of the premises of neoliberalism that he’d bought into earlier in his career; his proposed parental-leave program wouldn’t look out of place on a Sanders-style policy platform. But for someone writing about men and economic inequality, Reeves has little to say about unions. “The issue of power in the labor market is one that Third Way people just massively understated,” Reeves told me. “If you were with Blair, it was almost a badge of pride to be anti-union. Looking back, I was a total wanker about some of that stuff.”

What also remains unexplored in Reeves’s work is the reason the United States doesn’t have a European-style welfare state. As Calarco argues in Holding It Together, it’s because the long-standing premise of the American welfare state is the uncompensated labor of women, who still do two more hours of household work per day than men. While Calarco applauds Reeves for encouraging men to enter into care-work sectors, she said he could do more to highlight the fact that those HEAL jobs do not pay well precisely because they have been considered women’s work.

“So much of this manosphere culture is tapping into that desire to find a way to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps,” Calarco added. While men may feel a specific sense of precarity, Calarco sees Reeves’s vision of male-focused policies as taking us farther away from the kinds of universal programs that could help address the precarity that people of all gender identities experience. Focusing on men, Calarco said, “actually leads to more skepticism of those kinds of universal policies, and discourages men from seeing themselves as represented in those kinds of universal policies.”

When I asked Reeves why his focus wasn’t on those policies, at first he replied flatly, “Because we’re not going to get them.” Then he paused to regather his thoughts. “I’m trying to incrementally advocate for some policies, and some changes in rhetoric, to help boys and men without really challenging the broader political economy within which that is taking place. I think that’s a legitimate criticism. You might say, ‘Well, in a different political economy, some of these issues would just be dealt with anyway.’”

For Niobe Way, a developmental psychologist at New York University who has studied boys and young men since the late 1980s, all of Reeves’s charts and graphs obscure the absence of an important explanation of why men are struggling—culture. In her recent book Rebels With a Cause: Reimagining Boys, Ourselves, and Our Culture, Way writes of “boy culture”: norms of masculinity that discourage boys at an early age from developing the social and emotional skills that could help them navigate a society built with women’s full participation in mind. The “soft skills” that are needed to excel in school and in a postindustrial labor market are the same skills that Way says boys are socialized from an early age to suppress.

“Boys have been telling us what’s at the root of their problems and how to solve it for almost four decades now. And we’re not listening,” Way said. “Masculinity needs to be reimagined? What the hell? No, humanity needs to be reimagined.”

In the days after Trump’s reelection, a post from the Gen-Z white nationalist Nick Fuentes went viral: “Your body, my choice.” “I haven’t been in a meeting since the election where someone hasn’t brought that up,” Reeves said. He sounded impatient. “Do we think that the median 28-year-old man who voted for Trump thinks he should have control over a woman’s body? I don’t.” In an article on AIBM’s site last July, Reeves used data from the General Social Survey to argue that young men are not backsliding on their support for women’s rights.

“I disagree with him on that,” said Daly, the Young Men Research Initiative founder. “Men and boys are viewing equality as problematic. That’s something that I certainly wish were not true.” Part of this reaction, she said, is the post–Me Too moment combined with a pandemic that drove young people inside and into mostly single-sex online spaces. “Young men feel like they’re being blamed for things they didn’t do. We might disagree with that, but if we want to change any minds, we have to acknowledge that’s some of what’s causing this.” Emba, the Atlantic columnist and AIBM board member, told me that in the days after the election, she’d attended a closed-door gathering of wonks, politicians, and journalists who were caught off guard by the male vote. “If there’s a big pot of grievance that isn’t being addressed, clearly something is going to happen, and something did happen,” she said.

Reeves has gone to battle with men’s rights activists who exploit those grievances, including the “godfather” of the manosphere, Rollo Tomassi, whom he debated, voice raised, on Dr. Phil. In some of those arguments, Reeves had to concede the point that mainstream sources sometimes failed to acknowledge gender disparities in cases where men were lagging behind women. But where a men’s rights activist sees a feminist conspiracy, Reeves sees a robust infrastructure of organizations that advocate on behalf of women, which emerged out of a decades-long struggle against systemic discrimination. “I would not expect a women’s think tank or a women’s advocacy organization to be doing work on what’s happening to men,” he said. “It’s quite literally not their job.” It was in those moments that Reeves thought Of Boys and Men might turn out to be his life’s work. “I realized it’s no one’s job to wake every day and think about this,” he said. If there were no examples of what Reeves calls “boring institutions” advocating for men, the Andrew Tates of the world would use the silence to bolster their argument that men are a persecuted class.

Reeves founded the American Institute for Boys and Men in 2023 with the goal of having it be that mainstream institution—a responsible, empirically grounded bulwark against an increasingly ugly backlash against women. He wants to deescalate the growing gender polarization, with the ultimate goal of a country and world where one’s gender identity is less salient, not more, he told me. He argues that young men are not finding a new political home on the right—they still support liberal policies on climate, abortion, and healthcare—but that they don’t see a place for themselves on the left, either.

What is true is that young men today are much less likely to describe themselves as feminists. Reeves believes that’s because they think “feminism is about telling men they’re toxic, that they’re part of the patriarchy, and they should just shut up,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean they don’t think their sister should have the same opportunity.”

While Reeves hasn’t had as much success lobbying politicians as he’d hoped, he counts Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy among his biggest fans in office, along with California Representative Ro Khanna, Maryland Governor Wes Moore, and former surgeon general Vivek Murthy. “We’ve been on this journey since the 1980s to lionize the individual and marginalize the common good, and I think that’s been really harmful for men,” Murphy told me. “The left, broadly, doesn’t talk about men, because we’re really uncomfortable with that conversation. Richard is providing this gift, which is a safe place to talk about these issues and help on terminology and language.”

Filipovic told me that part of why she thinks Reeves’s work has taken hold, and why he hasn’t received more outspoken public criticism from feminists, is that his book was published during a time of liberal soul-searching. “How have we gotten to this point where there is this reactionary anti-feminist movement animating our politics, animating our culture, and radicalizing young men?” she asked. Reeves’s work made her reexamine rhetoric that in the past could feel playful and cathartic, like “Male Tears” on coffee mugs. “There are men who can take it on the chin. But for men without a college degree, without many job prospects, and who are looking for an organizational theory that can explain ‘Why am I here? What am I doing? Why do I feel the way that I feel?’—that kind of daily message from progressives and from feminists, including myself, that there is something about you that is inherently bad and toxic, is not helpful,” she said.

Reeves does not believe that masculinity is toxic. But he does believe it’s fragile. Drawing on anthropology, Reeves argues in Of Boys and Men that manhood is harder-won and more easily lost than womanhood “because of women’s specific role in reproduction.” He criticizes the right for greatly overstating the significance of biology and the left for being unwilling to acknowledge the role of biology, for fear that it will be used to justify discrimination. (Reeves has also written that transgender and nonbinary identities are just as sincerely felt as cisgender identities.) While biological differences, he says, “are not determinative of human behavior,” they do matter, and “little good will come from denying [them].”

This leads to Reeves’s most controversial policy recommendation. Because boys’ brains, on average, are slower to develop during adolescence, Reeves wants to “redshirt the boys,” or hold them all back for a year before they start kindergarten. This question of how to weigh biology—especially in education—is one that has long polarized the field, said the psychologist Michael Reichert, the director of the Center for the Study of Boys’ and Girls’ Lives at the University of Pennsylvania and a coauthor of Equimundo’s “State of American Men” report. “To the extent that Richard has caused controversy, it’s really along those very familiar fault lines,” he said. “We have been producing poor outcomes for boys for generations and rationalizing it based on the assumption that boys are essentially feral beasts that need to be tamed.”

Niobe Way believes that Reeves is “fanning the flames” of a gender divide that is “more ferocious than it’s been for a long time.” By bifurcating gender, as Reeves does, Way says that you will inevitably end up privileging one side over the other. “Richard gets the point that boys and men feel put on the bottom of the hierarchy of humanity. But the solution is not to flip the hierarchy and then to only focus on boys and men. You can’t say that the problems that boys and men are facing are somehow fundamentally different from the problems of girls and women. And that is a Richard Reeves assumption,” she said.

As Reeves was speaking at the Global Women’s summit, I heard someone behind me quietly saying “yes” after each beat. I caught up with her outside in the reception hall. Her name was Priestley Johnson, and she directs the USA division of Girl Up, an initiative of the United Nations Foundation. “I was in that room like, ‘Oh my God, what side am I on right now?’” she said with a nervous laugh.

Johnson said she thinks many women are still “licking their wounds” after an election in which so many voters showed that they did not prioritize reproductive rights. But, she continued, “I think we are at a critical place to ask why. I don’t think it’s based on the issues; I think it’s around the sentiment of men not being included in the conversation.” She felt like the panel we’d just attended demonstrated this. “The ‘mommune’—like, where are men going? Oh, they’re dying? We should be talking about their healthcare then, right?”

I met up with Reeves in the greenroom afterward, and we headed out to another café. As he walked through the reception hall, he was greeted like one of the celebrities on the bill. “I’m constantly waving your book in front of people’s faces,” said a woman named Sarah Hall, who told Reeves that she works with college football players. “I wish more people knew about what you were doing.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“I’m trying,” Reeves said, adding that he hopes to launch a “Coach for America” program with help from the former Ohio representative Tim Ryan.

Quari Alleyne, a senior video producer at The Washington Post, was practically glowing as he approached Reeves. “I have come to sing your praises, Mr. Reeves,” he said. “I have to tell you how much I appreciate what you’re doing.”

“Coming over and saying that means a lot,” Reeves replied. “It can be a lonely space.”

A woman named Kevonne, who asked me not to share her last name and to describe her as a Black mother, had a cathartic reaction to hearing Reeves speak. She said her son had been unfairly disciplined in school and had “tons of different diagnoses put on him.” Reeves told her that he has a Black godson and that there’s a chapter in his book about the specific barriers faced by Black men and boys, including grossly disproportionate rates of school discipline.

“I’m going to buy your book,” Kevonne said. “Are they selling it here?” She motioned toward the makeshift gift shop next to us. “That’s a very interesting question,” Reeves said, cracking a mischievous grin. As it turned out, Of Boys and Men was not being sold at the Washington Post Global Women’s Summit. But given how the book’s message had gone over, perhaps it should have been. In real time, one could see there was a demand for the kind of “permission space” that Reeves had made it his life’s work to create.

“Your son is lucky to have you,” Reeves told Kevonne, and headed off to the elevator with a smile.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Parts of LA Are Not Going to Be Habitable Parts of LA Are Not Going to Be Habitable

Insurers have figured out that risk is too high in parts of California. We need to re-conceive how people are housed, and fast.

How Covid Sickened the National Psyche How Covid Sickened the National Psyche

While the US was a troubled nation long before the coronavirus, our failure to treat the pandemic as an enduring emergency helped birth this nasty moment.

White Flops Rejoice! White Flops Rejoice!

DEI is being snuffed out in DC. Mediocre whiteness reigns. And we’re all going to suffer for it.

The Washington Post’s Dark Turn The Washington Post’s Dark Turn

Columnist and editor Ruth Marcus has become one of many journalists to resign from the newspaper following increasing interference by its owner Jeff Bezos.

DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook DOGE’s Private-Equity Playbook

Elon Musk's rampage through the government is a classic PE takeover, replete with bogus numbers and sociopathic executives.

Mahmoud Khalil’s Abduction Is a Red Alert for Universities Mahmoud Khalil’s Abduction Is a Red Alert for Universities

Schools across America have a choice: Defend their students against Trump or be complicit in his crimes.