Yto Barrada’s Rules of the Game

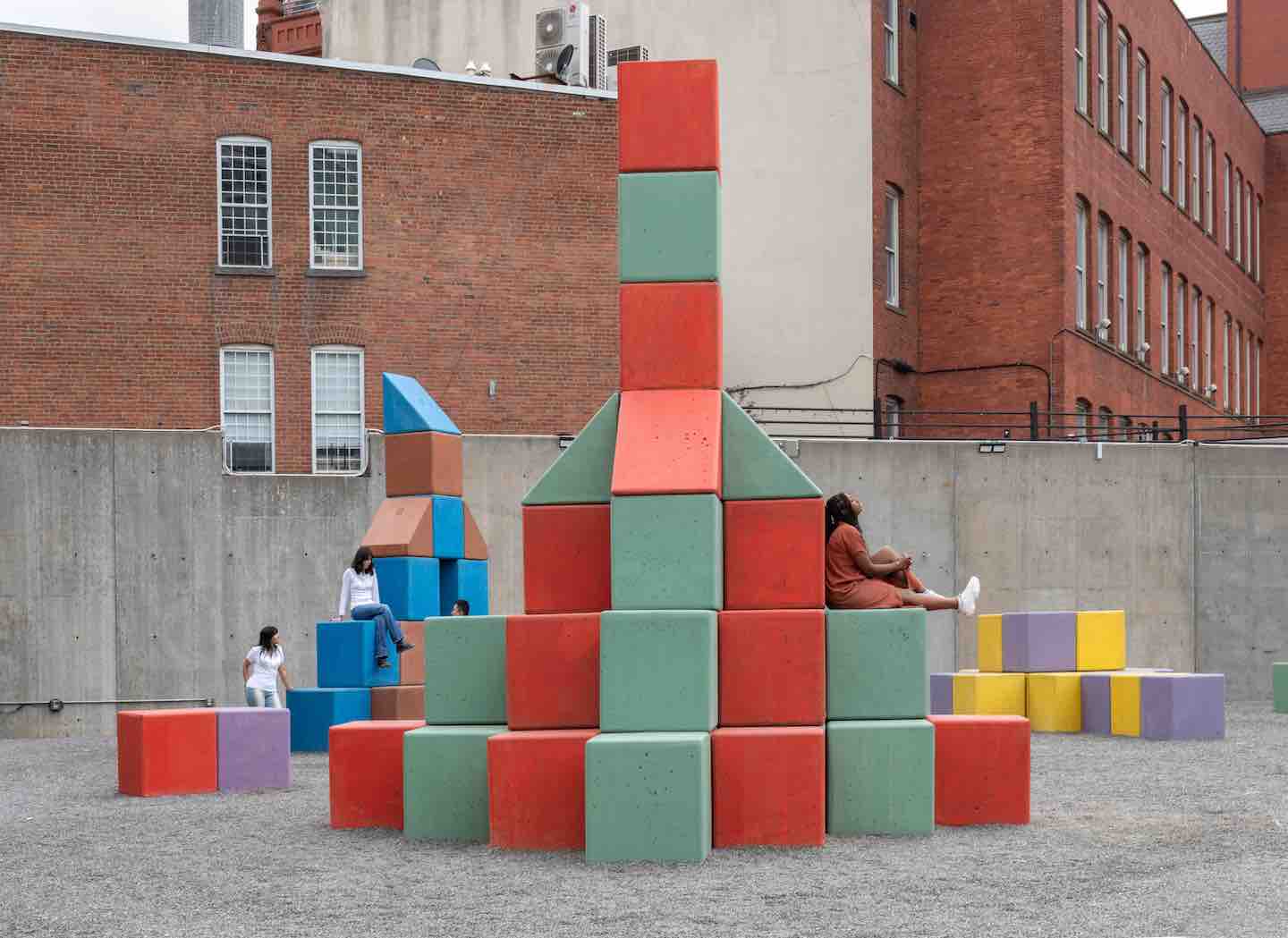

The artist’s installation at MOMA PS1 is not just a public work of art in the form of a playground but also comment on postcolonial architecture and experimental pedagogy.

Yto Barrada

(Marissa Alper)

On the day Yto Barrada’s commission Le Grand Soir opened at MoMA PS1, as we moved between passages of sunlight and shade, the artist watched a child leap from a stroller and bolt onto the installation. “I think this is the only sculpture to be approved by the city’s playground safety commission,” she said with a smile before discreetly puffing on a cigarette.

Schools erected during the Gilded Age had a penchant for Neoclassical motifs that honored the intellectual influence of ancient Greece; their Gothic Revival flourishes bespoke a European pedigree. At the center of MoMA PS1 is a Romanesque building, which was originally built as Long Island City’s first public school, adorned with gargoyles, turrets, and ornately bricked gables that convey an imposing pedagogy. Playgrounds weren’t prevalent in the United States until the 1900s, and the school lacked a dedicated space for play. On its surface, Barrada’s installation seems to rectify this history—yet it’s charged with subversive political intent: The pleasantly colored cubes that will occupy the museum entrance’s breezeway into 2026 are actually a way of infusing a cheeky sense of anarchy into the building’s imperial authority.

Le Grand Soir consists of 97 concrete cubes, each weighing approximately one ton, stacked in three pyramidal structures. Rendered in a palette that references Moroccan motifs, such as a lily indigenous to North Africa and container ships that traverse the Strait of Gibraltar, their sides are etched with Arabic titles: tqal (“weight”), bourj tarbaite (“tower of four”), and bourj benayma ou chebaken (“tower lift with net”). These are the names of acrobatic stunts, and each group of blocks is arranged in a rough resemblance to a human-pyramid formation. If you climb the sculptures, you can see just over the concrete wall that encircles PS1’s yard to survey the sidewalks outside. From here, the museum seems a less enclosed and forbidding space; the simple change in elevation is enough to give a momentary feeling of liberation. This, for Barrada, is a minor revolutionary act—one she likens to the anticipation she feels during periods of social upheaval. Through her project, she wants to acclimate us to the feeling of transcending even the most mundane structural limitations.

Barrada, who will represent France at the 61st Venice Biennale in 2026, was born in Paris and raised in Tangier. The artist now runs two of the city’s epicenters of contemporary art: Cinémathèque de Tanger, North Africa’s first art-film theater, and a residency program called Mothership, where she has revived traditional dye-making techniques using indigenous plants grown in the center’s garden. The city of Tangier and its eclectic architecture—its traditional dwellings sitting cheek by jowl with Brutalist public works—have long influenced the artist’s practice. Across Morocco, the stark, utilitarian buildings of designers like the French architect Michel Écochard and the Moroccan Elie Azagury—respectively the pre- and post-independence directors of the Groupe des Architects Modernes Marocains, or GAMMA—were meant to signal the strength and sturdiness of a country shrugging off the violent rule of the colonial French protectorate and coming under the stewardship of an increasingly despotic monarchy. “After independence, vernacular-minimalist architects did schools and public housing for workers and neighborhoods,” Barrada told me. International Modernism became the language of both Morocco’s working-class neighborhoods and its public education. Brutalism may have begun as a French cultural export in Morocco, but it came to embody a particular expression of place.

In 1960, four years after independence, an earthquake leveled Agadir—a city that Barrada described as “Morocco’s Miami” and a destination for French tourists to fulfill colonial fantasies. The quake killed as many as 15,000 people, or approximately a third of the city’s population. Barrada revisited the destruction in a 2018 commission presented at London’s Barbican Centre, where dancers reenacted a surrealist poem written by Mohammed Khaïr-Eddine. The text concerns a civil servant tasked with investigating Agadir’s reconstruction as he’s seized by hallucinations about the city’s past and future. Barrada layered a recitation of the poem with what she called “the grammar of Brutalism”—blueprints of utopian concrete forms, woven armchairs, photographs of industrial gardens—as a way to reflect on the infrastructure of national identity. “What do you do after absolute destruction?” she asked me. “Do you rebuild the city exactly the way it was? Do you reinvent the city? Does disaster give you a chance to reevaluate?” With its covert references to Morocco’s syncretic culture and colonial history, Le Grand Soir offers a subtle but sharp-edged critique of the contemporary museum and former school building initially erected as part of a grand civic project to assimilate immigrant families and engender a sense of nationalism and pride in an ascendant New World empire.

All architecture is utopian, insofar as it determines the parameters and possibilities of its residents’ lives. Just as the post-structuralists believed that the patterns and structures of language dictate those of the mind, Barrada’s project suggests that our built environment, in a very real and simple sense, defines the borders of our imagination—and, as such, any act that serves to dismantle walls, barricades, and barriers, no matter how modest, is charged with a moral imperative.

Barrada’s project draws on the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne, or CIAM—an organization whose founders, including Le Corbusier and Karl Moser, revised the rules of universalist architecture to emphasize studying the quotidian life of local residents and mapping that activity in a color-coded grid. It also draws on the writings of the French educator Fernand Deligny, who in the 1970s organized a commune for autistic children to live free from institutionalization. Deligny’s team traced the children’s routes as they wandered the commune in organic, tangled paths. The result suggests, Barrada told me, a way for art to break down the restrictions on movement and ideas that are latent in all architecture and to create a more egalitarian society by rooting design in exploration, play, and observation.

“For a long time, play wasn’t for children,” Barrada said. “It was too serious, like research.” At its heart, Le Grand Soir offers a simple transposition: the history of nation-building rewritten as the rules to a game. “I’m thinking about the structural invention of society—and also creative, nonproductive freedom,” she said. “That’s what play is.”

In Le Grand Soir’s three cube-based structures, any number of hidden references—postcolonial architecture, revolutionary ideology, pedagogy, experimental aesthetics—all cohere into an object of seemingly perfect geometry. Barrada is a disciple of Marcel Bénabou, the permanent provisional secretary of the experimental literary movement OuLiPo as well as the guardian of the novelist Georges Perec’s archives and a historian of African resistance. Bénabou writes by starting with an existing text as his point of departure—“It could be the Bible or a dictionary of etymology,” Barrada noted—and arriving somewhere different. “In French, we say avancer à reculons, which means ‘advancing backwards.’” As we were speaking, she hopped several times to illustrate. “It’s about negotiation, bending material—even if it’s concrete—to allow the intrusion of all of the things that I’m interested in, that I want to research.” The recombinant nature of her process allows her to approach history in a nonlinear fashion, tying together influences that might seem disparate on the surface.

Barrada used, as Le Grand Soir’s point of departure, the holes left by rebar in MoMA PS1’s concrete walls. Barrada was reminded of similar construction methods used to build terracotta casbahs, the medieval citadels found across North Africa, leading her to research a school of acrobatics that grew out of a mystical Sufi brotherhood founded by the 15th-century marabout Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa. Drawing on Berber ritual practices, Moussa developed elaborate human pyramids that his followers used to scale the ramparts of the citadels and defend their casbahs. They believed their feats were charged by a baraka, or a blessing from God, and over time these military maneuvers became a way of achieving spiritual elevation.

In the 19th century, American and German entertainers enticed these troupes, known as the Children of Sidi Ahmed Ou Moussa, to perform at fairs and circuses that traveled across Europe and the United States, where the acrobatics were shorn of their military and religious significance and recast as Orientalized entertainment; several ethnic groups were collapsed under the exonym “Moor” and performers dressed in a romanticized approximation of Berber garb. Photographs that Barrada uncovered in her research show acrobats arriving in New York and the metropoles of Europe dressed as nomads from the Rif—the northern mountains of Morocco where Spanish occupiers waged a war against a guerrilla resistance (whom they inaccurately called Arabs) during a 1920s colonial conflict that triggered France’s reentry into its former protectorate.

Le Grand Soir braids these tensions with vignettes from Barrada’s family lore in the years following Moroccan independence. The artist’s father, the journalist Hamid Barrada, was condemned to death by the regime of King Hassan II during Morocco’s Years of Lead, the period between the 1960s and 1980s when dissidents were violently repressed, tortured, and disappeared. She finds echoes between the acrobatics of Moussa’s Sufi fighters and her father’s nighttime flight from the country with the aid of French Resistance leader Lucie Aubrac. “The story of his escape starts on a terrace,” she said, “jumping from rooftop to rooftop” like a gymnast while dressed in a woman’s djellaba that revealed his hairy legs. At one point, she considered engraving Le Grand Soir with excerpts of her father’s dispatches from his exile in Paris, before deciding that his story should comprise “its own form of concrete poetry” in a future project.

Although these family stories aren’t readily apparent in the sculptures, they exist as a kind of mental scaffolding, a structure for telling the history of her country from its medieval dynasties through its subjugation and independence. “Mixing the mystic history of these warriors with my own family history means the commission is not actually a monument,” Barrada said. “It’s an homage, an anti-monument to these generations of tumblers and acrobats who came here to be monkeys in your circus.” Still, there is joy here—not the high-minded variety of the kind museums often encourage or a sentimentalizing nostalgia, but something raw and almost unmediated. It involves bright colors, children at play, simple word games. These small pockets of unexpectedness are what Barrada is after—areas where one’s perspective changes, moments when one’s attention shifts. That is where, she would argue, some new idea can take root, some new world can begin.

Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Will Scholars Take a Stand Against Scholasticide in Gaza? Will Scholars Take a Stand Against Scholasticide in Gaza?

The fight inside the historical profession heats up.

Rumaan Alam’s Haves and Have-Nots Rumaan Alam’s Haves and Have-Nots

With his latest novel, Entitlement, he asks: Can wealth inequality make you lose your mind?

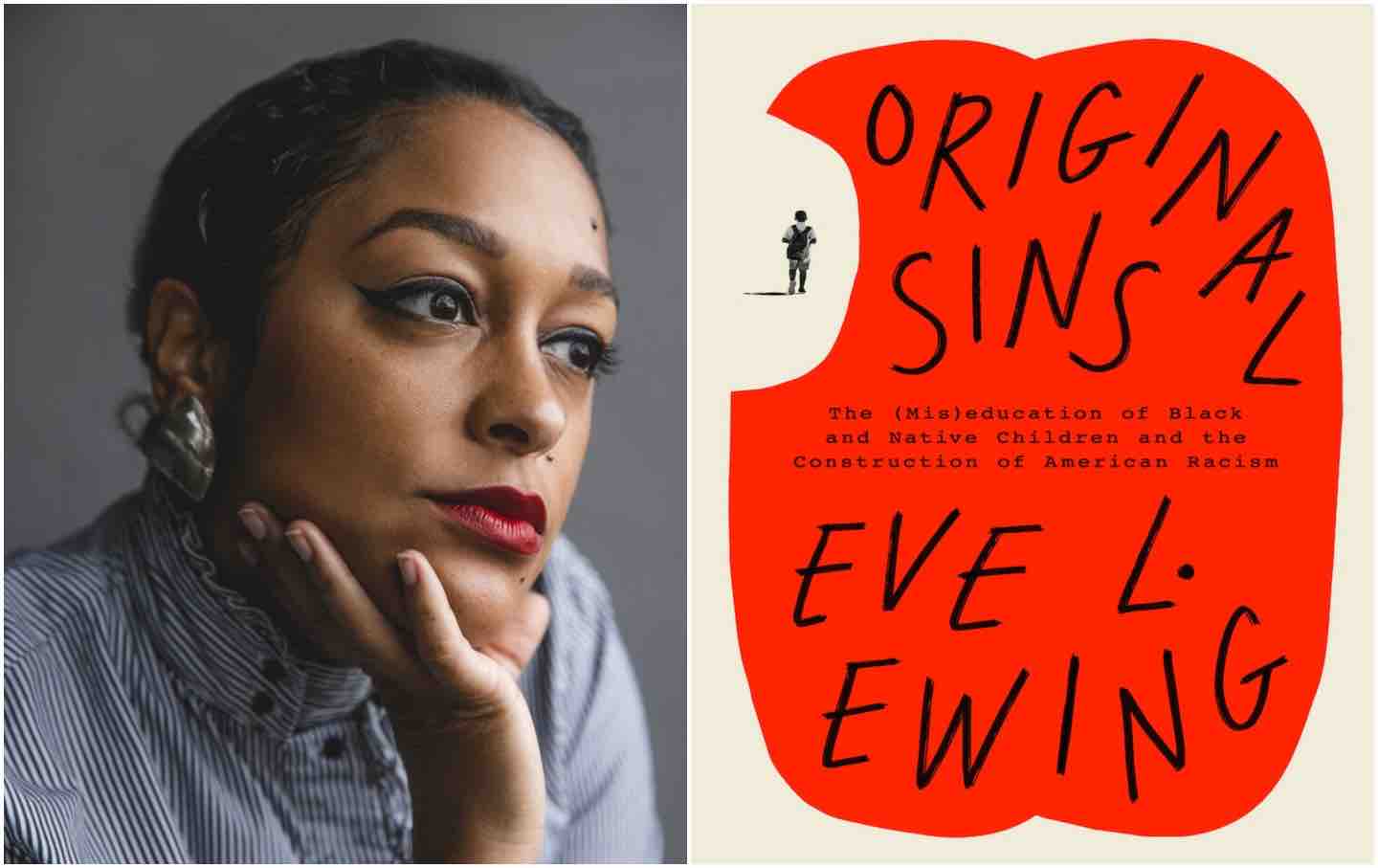

How Do We Combat the Racist History of Public Education? How Do We Combat the Racist History of Public Education?

A conversation with Eve L. Ewing about the schoolhouse’s role in enforcing racial hierarchy and her book Original Sins.

Art Spiegelman and the Inescapable Shadow of Fascism Art Spiegelman and the Inescapable Shadow of Fascism

The creator of Maus has learned that the past is always present.

Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s Voice From the Past

The Pakistani qawwali icon sang words written centuries ago and died decades ago. He’s got a new album out.

How the US Courts Rewrote the Rules of International Trade How the US Courts Rewrote the Rules of International Trade

Shaina Potts’s Judicial Territory examines how the American legal system created an economic environment that subordinated the entire world to domestic business interests.