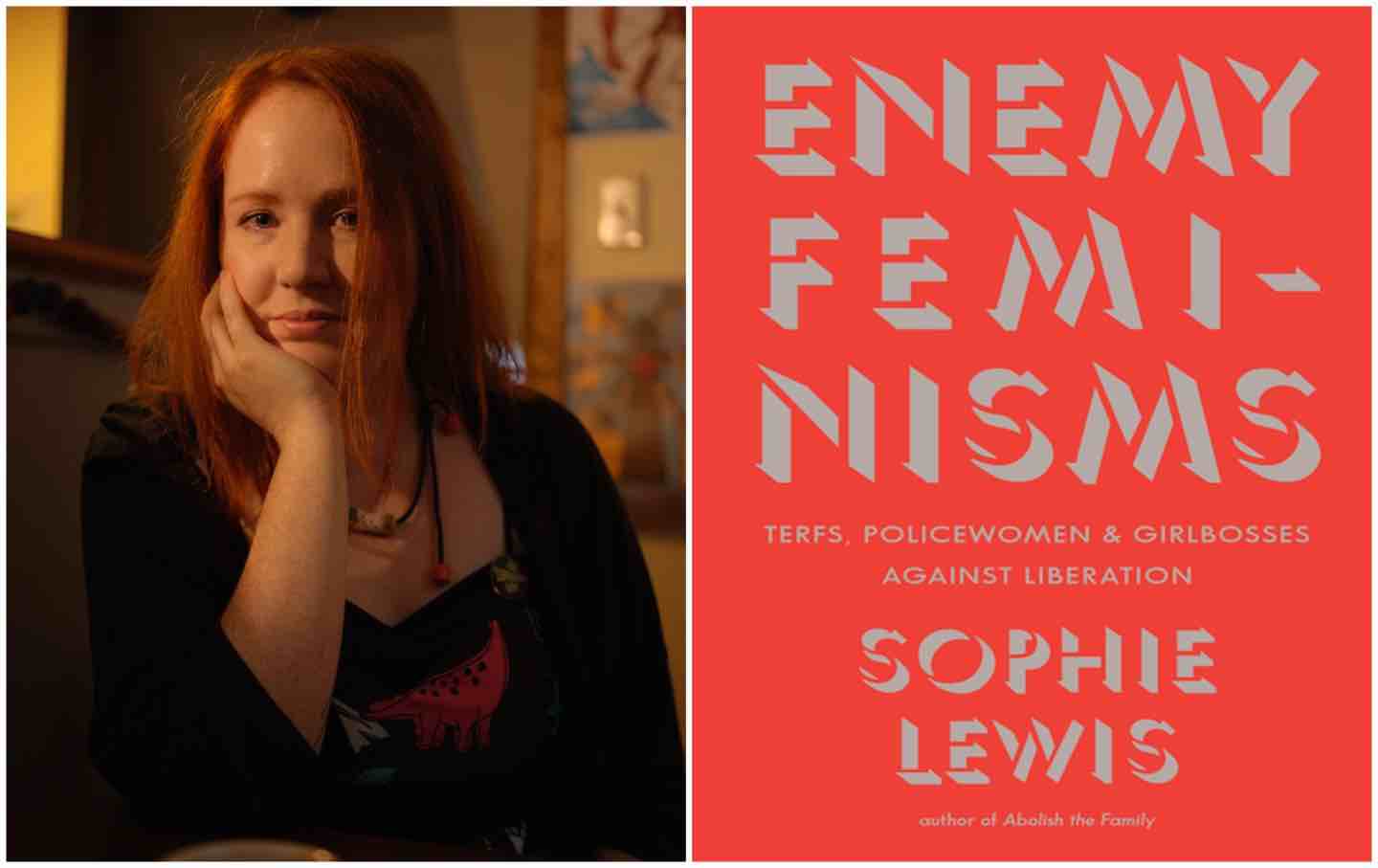

The Life and Death of Conspiracy Cinema

Why did Hollywood lose interest in making paranoid thrillers like The Parallax View and Three Days of the Condor? Was it a change in the culture? Or a change in the marketplace?

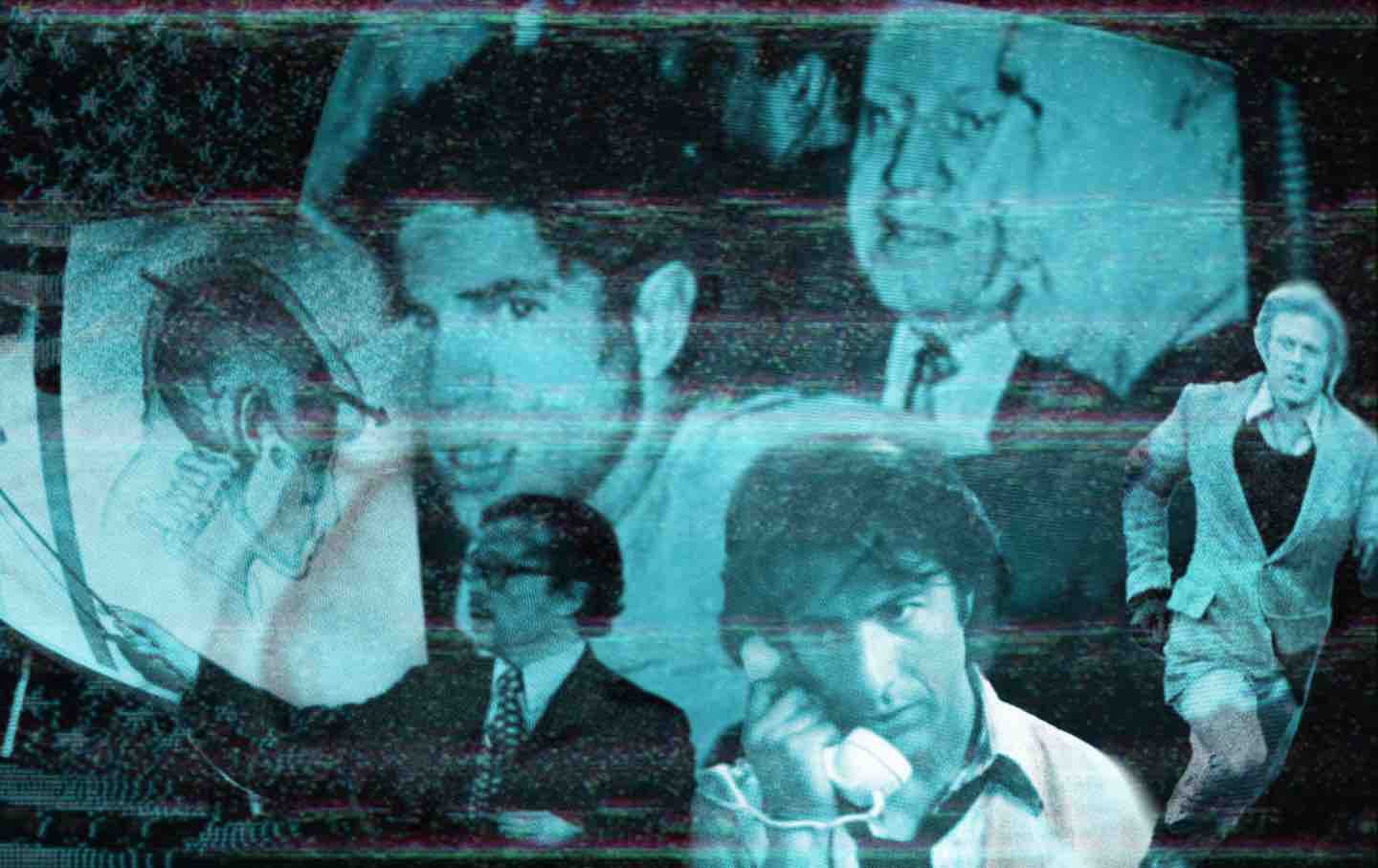

Dr. Michael Baden giving a testimony before the House Assassination Committee on the shooting of President Kennedy, 1978; a television picture, broadcast in May 1977 of Sirhan Sirhan being arrested after his shooting of United States Senator Robert Kennedy; Dustin Hoffman in All The President’s Men, 1976; Robert Redford in Three Days of the Condor, 1975.

(Illustration by Ludwig Hurtado; photos by Bettmann; Getty Images; Ernst Haas; Hulton Archive; Screen Archives; Paramount)

Alan J. Pakula’s 1974 film The Parallax View begins with a sleight of hand. The film follows Joe Frady (Warren Beatty) as he investigates a series of mysterious deaths surrounding the assassination of a presidential hopeful, who is murdered in Seattle during a Fourth of July campaign stop at the top of the Space Needle. After the candidate is shot, his security team pursues the killer to the top of the tower, where, after a tussle, he falls to his death. The bodyguards stop and peer over the edge, relieved that the assassin is dead but unable to hide their shock that the guy just fell 600 feet, his remains splattered on the concrete below.

But there was a second shooter. He escaped during the confusion through a haze of gunsmoke, holstering his gun under his jacket while the security team chased down the gunman closest to the senator. We see the other assassin when the camera puts us back at street level, smiling as he walks away from the scene of the crime.

The movie’s opening doesn’t set it apart from many other thrillers propelled by the need to solve a murder. But The Parallax View is not about any one murder: It’s about systems and how they exert invisible influence over the people within them. In the very next scene, the camera steadily pulls in to focus on a panel of seven officials tasked with investigating the assassination. They’re seated across a dais in a courtroom, a heavy wooden seal hanging behind them. The ultra-wide-angle shot distorts the image slightly, as if the shot is curling gently around a lens. It’s a voyeuristic trick, like you’re looking through a peephole or watching a surveillance tape; you’re seeing something that you shouldn’t be. “This is an announcement, not a press conference,” the commission’s spokesman says. “There will be no questions.” The opening credits roll from there.

The Parallax View was the product of a profoundly anxious and conspiratorial national mood: The country was still reeling from the Vietnam War, a series of political assassinations—President John F. Kennedy in 1963, Malcolm X in 1965, and both Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968—and era-defining scandals in the Pentagon Papers and Watergate. This series of national tragedies shattered the façade of postwar peace and awakened many Americans to the possibility that not everything was as it seemed. (Apparently, Beatty and the rest of the crew would watch the Watergate hearings during set breaks, which gave Parallax an extratextual layer of anxiety.)

The film is bleak both in ambiance and execution thanks to cinematographer Gordon Willis (The Godfather, Annie Hall), known as the “Prince of Darkness” for his skillful balancing of light and shadow. We see Frady wrapped in shadows for much of the film, a literal reflection of how little he understands about what’s going on around him—he’s a shaggy-haired representative of the 1970s public, who have also realized they’ve been left in the dark and are fumbling around for answers.

The Parallax View was the middle entry in Pakula’s “paranoia trilogy,” which began with the erotic thriller Klute (1972) and ended with the more hopeful All the President’s Men (1976) and its heroic depiction of journalists unraveling Watergate. The progression of the trilogy—from a small-scale urban conspiracy to a national one and then the solving of one—roughly mirrors, in retrospect, the slow shift from pessimism to something resembling collective closure, or at least fatigue with constantly thinking about the state of things.

Pakula was not the only director of the era whose films indexed all this pessimism and upheaval: Works like Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974) and Sydney Pollack’s Three Days of the Condor (1975) were rife with anxiety about the country’s future, unsure if change was possible. At the end of Condor, Joe Turner (Robert Redford) is standing outside of the New York Times building face-to-face with his antagonist, CIA deputy director Higgins (Cliff Robertson). Turner explains that he’s just revealed a massive conspiracy to the paper’s reporters and starts to walk away. “Hey, Turner, how do you know they’ll print it?” Higgins says with a slight smirk. Turner, so guileful and confident throughout the movie, has let doubt creep in. “They’ll print it,” he says, before Higgins volleys Turner’s insecurity back at him: “How do you know?”

Only a year later, Pakula would give us a movie that affirmatively answers that question with All the President’s Men, as Bob Woodward (Robert Redford again) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) investigate the Watergate conspiracy and eventually topple Nixon. It gave audiences something of a happier ending, which they were apparently hungry for after years of cynicism. “If the Sixties and early Seventies were, at least in part, periods of disillusionment, the late Seventies and Eighties brought a process of re-illusionment,” the film critic J. Hoberman wrote in Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan.

Hoberman’s book braids together the political, cultural, and cinematic threads of the 1970s and ’80s, using Reagan’s rise from B-list actor to governor of California to president of the United States as a guiding timeline. For Hoberman, movies like Robert Altman’s Nashville (1975) and Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975) represent not just a difference in artistic vision, but also a rift in philosophies that set the tone for national cinema. “Two kinds of filmmaking passed each other…. Nashville was intellectual and exclusive, Jaws visceral and populist; Nashville looked back to the 1960s, Jaws ahead to the 1980s,” Hoberman wrote. Jammed in the middle of these two divergent paths were films that tried to put a nation’s anxiety on the big screen. But that movement was short-lived, and the conspiratorial cinema from Pakula, Pollack, and Coppola was eventually metabolized by an industry and a country willing to forget the bad times.

Reagan’s ascendance at the end of the 1970s can be credited to many factors in the late ’70s political environment—including a few conspiracies of his own—but one of the most winning aspects of his campaign was his rosy outlook on America’s prospects and the country’s role as a moral force in the world. Hoberman considers Reagan’s ability to “invent” a pristine American past—by dint of his experience in Hollywood—as one of the main sources of his appeal: “His mandate wasn’t simply to restore America’s economy and sense of military superiority but also, even more crucially, its innocence.”

Included in that was a return to faith in institutions. According to the Pew Research Center, more than 75 percent of the American public trusted the federal government to do what was right in 1964. A decade later, that number had fallen to 36 percent before declining further, reaching 25 percent during the Carter administration. After Reagan was elected in 1980, that trend line reversed: By the end of his first year in office, 40 percent of Americans said they trusted the government, a sentiment that remained stable save for a short-lived drop during the Iran-Contra affair. (Still, the public would never trust the government again at the rate they did in the first decades of the postwar years and the start of the baby boom.)

Unsurprisingly, this change in mood was reflected in Hollywood. The studio system that fostered the careers of auteurs like Pakula, Pollack, and Coppola became increasingly concerned with the things that mattered to Americans in the ’80s: money and the Cold War. It was something of an inauspicious sign that the dawn of the Reagan era coincided with Michael Cimino’s epic bundle of a western, Heaven’s Gate (1980), which some film historians consider as the moment the studio system began to turn on the generation of misfit talents that it had depended on for salvation through the previous decade. Instead, Hollywood would embrace big-budget blockbusters as a way to avoid the financial tumult of the 1970s, when TV siphoned audiences out of the theaters and onto their couches. Movies like Jaws (1975), Star Wars (1977), and Grease (1978) set the stage for an era that would mature during the Reagan years. Investment in films became more concentrated as the studios consolidated and executives pushed their chips onto safe bets, neglecting less conventional films—a strategy that would come to define Hollywood for decades to come. Conspiracies never left the movies, though; they would become just another plot device.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The Mel Gibson and Julia Roberts blockbuster Conspiracy Theory was released to mixed reviews and a modest box office return in 1997. The movie follows taxi driver Jerry Fletcher (Gibson), who ticks every box on the crank’s bingo card: black helicopters, the Freemasons, MK-Ultra, the New World Order, fluoride in our drinking water, the deep state. We’re meant to see Fletcher as a lunatic initially, and indeed, Justice Department lawyer Alice Sutton (Roberts), whom Fletcher stalks before finally being allowed to share his theories, considers him exactly that. Fletcher’s ideas are like paranoid Mad Libs—NASA is going to kill the president with an earthquake; the Vietnam War was fought because Howard Hughes lost a bet to Aristotle Onassis—and Sutton listens with engaging patience. The first 20 minutes of the movie are strangely rom-com-esque, with an upbeat score and flirty dialogue. “You think I’m crazy,” Fletcher says after peppering Sutton with his theories. “I think you’re different,” she replies.

Shortly afterward, though, we find out that Fletcher’s theories might be true. The government does have a file on him, and after he tails some spooks into a building with “Central Intelligence Agency” written right there on the directory board, he’s abducted and tortured by the CIA’s Dr. Jonas, played by Patrick Stewart. (Hearing Stewart as a deep state torturer say “gravy for the brain” as he injects his subject with LSD is one of the high points of the film.) The spies want to know how he found out about all their plans and what else he knows.

It’s in that moment of feverish vindication that Conspiracy Theory loses its purpose as a movie: Fletcher’s transformation from crank to hero is frictionless, and the ending, you might already have guessed, is a happy one. In another era, Fletcher’s rabbit holes might have led somewhere interesting, but with two of the 1990s’ biggest stars attached, the film needed to be a smash and sacrificed nuance and subtlety in the process. (Its anemic box office returns indicate that audiences didn’t think much of that strategy, either.)

Several other conspiracy-driven movies in the 1990s followed the same script. The Firm (1993) sees Tom Cruise navigate a mobbed-up law firm and duplicitous FBI agents before driving off into the sunset; The Net (1995) ends with Sandra Bullock getting her life back from cyberterrorists, her tormentor arrested on live TV. Enemy of the State (1998) doubles down on the happy endings: Will Smith is reunited with his wife, while Gene Hackman relaxes on a tropical island. Even Pakula wasn’t immune to these shifts: His final film, The Pelican Brief (1993), features Julia Roberts and Denzel Washington unwrapping a conspiracy that goes to the very top of the government, but instead of the uncertainty that defined Pakula’s early films, Pelican resolves into a potboiler.

The shift in how conspiracy theories are presented from The Parallax View to Conspiracy Theory reflects both industrial and cultural evolutions. Hollywood needed to make movies with guaranteed mass appeal in order to stay solvent, so uncomplicated blockbusters with an easily digestible morality became dominant. This mood has never left Hollywood, and in the IP era, as studios hunt for bankable franchises, there is little appetite for movies that aren’t immediately comprehensible to mass audiences. But conspiracy theories have never been more present in American life, and paranoia seems permanently baked into the public imagination. What has changed is the venue for these stories—from the big screen to smaller ones.

In 2003, the screenwriter Dylan Avery was doing research for a fictional film about 9/11 when he became so convinced by the different conspiracy theories about that day that he decided to make a documentary detailing how the attacks were orchestrated by the US government.

Loose Change is less a film and more like a piece of paranoid collaging. Much of the original 2005 version is made up of archival news footage and photographs backed by a trip-hop soundtrack. Avery narrates in a tinny monotone, offering up theory after theory: the missing airplane engines from the Pentagon crash, the impossibility of jet fuel melting the steel beams of the Twin Towers, the security cameras at the World Trade Center being disabled in the days leading up to 9/11. Avery updated the film several times over the next few years, removing some of its more dubious theories (e.g., a missile hitting the Pentagon) and cleaning up some of the editing. I remember watching that version high in a friend’s dorm room and being very bored.

YouTube would launch a few months after Loose Change’s release, and the free video-hosting platform would spread its wobbly collection of theories like a virus.The 9/11 conspiracy now had a marketing tool, and everyone could be in on it with a few clicks. Meanwhile, nascent social media platforms like MySpace and Facebook would help further balkanize the Internet, bringing communities of cranks together. There was something entrancing about the intimacy of all these individualized terrors that we could sort through in the privacy of message boards or, later, in the personalized feeds of our smartphones.

We’ve seen an unprecedented number of conspiracy theories mutate into viral hits, moving from ideas on the fringes to ones you hear about on the nightly news. But they seem less focused on illuminating how the world works and more like little totems of personality you can wear around your neck or put on your jacket. QAnon, Pizzagate, Sandy Hook deniers, Flat Earthers, “Stop the Steal” promoters, and those precious souls who don’t believe in the existence of birds are all reminiscent of social clubs or chat rooms. They’re a way of signaling to allies in a larger culture war. And conspiratorial thinking has also bled into more mainstream liberal spaces: A third of Joe Biden supporters thought that the attempted assassination of Donald Trump last summer was staged, and social media was awash in election fraud accusations this past November. Some of this is stoked by users looking for engagement and eyeballs, but at an individual level, many are simply looking for alternative explanations to confirm their sense that the world is not as it seems.

People are desperate for an explanation of their unhappiness, but as Baudrilliard wrote, “television and the media are increasingly unable to give an account of the world’s (unbearable) events.” This is where social media, I think, has changed the way we process information: On TikTok and YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, paranoia circulates freely because it seems easier to indulge in a smaller, more private version of reality with fellow travelers than to come to a shared consensus on why everyday life feels so awful. There is a banal truth in what conspiracy theories offer to their adherents on these platforms: They arise from the powerlessness to enact change in life on a collective or individual level, and what emerges, then, is a feverish hunt for explanations. That may be why the recent release of National Archives materials related to the assassinations of JFK, Robert F. Kennedy, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was met with a collective shrug. Their murders were national tragedies but I’d argue that people are less interested in the cold facts of what happened than the surrounding conspiracies that muffle the truth about how power is cultivated and used in this country.

Hollywood has been slow to reflect this growing mood of discontent. Blockbusters have evolved into multivalence “cinematic universes” dominated by optionable IP from comic books and a never-ending conveyor belt of sequels. In fact, since 2010, all but two of America’s highest-grossing films have been a continuation of a previous movie franchise. One of those exceptions was a movie based on a children’s toy (Barbie); the other was a steroidal vision of US military power based on a book by a Marine marksman and serial fabricator (American Sniper). It’s not as if conspiracies have totally disappeared from mainstream theaters, but when they do pop up, as in the Captain America films, they’re continuations of the easy morality tales that emerged in the 1980s and ’90s. Even works that try and recreate this paranoiac atmosphere like Netflix’s recent limited series Zero Day feel almost silly in their literalness. “If the public finds out how deep this really is, I don’t think we survive that,” President Evelyn Mitchell (Angela Bassett) says in one of the final episodes. And, spoiler alert, they do find out! The entire conspiracy is exposed and the protagonist (and former president) George Mullen (Robert DeNiro) goes back to writing his memoirs. The good guys still win.

I’d argue that the most effective bits of mainstream commentary on how hopeless things feel are now satires like Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019) and Ruben Östlund’s Triangle of Sadness (2022), both of which show how the market makes monsters of us all. It’s notable that neither film is by an American director, which speaks to the paltry institutional investment this country gives to emerging voices whose commercial potential may not be immediately discernible. It’s hard to imagine the American studio system fostering talents like these, let alone another like Pakula.

I thought of the last scene in The Parallax View, which speaks to how much and how little has changed. The audience is back in the committee room, and Pakula uses the same fish-eye lens, except this time the camera pulls out slowly while a spokesperson reads from a statement nearly identical to the one used at the beginning of the film. As we move farther back, every face sitting on the dais is eventually cast in shadow, the room itself shrinking to the size of an eerie diorama surrounded by black. It’s a reminder that we’re no closer to the truth, no matter what we think we saw.