Abortion Bans Upended Their Lives—Now They’re Fighting Back, One Story at a Time

Across the country, abortion storytellers are putting the struggle for reproductive freedom into powerful new words.

Shanette Williams sat patiently on the stage of an auditorium in Austin, Texas, staring at the photograph of her daughter Amber that was resting in her lap. The photo appeared on the front of a rose-dappled pamphlet, below the words “Celebration of Life” and “September 16, 1993–August 19, 2022.” Occasionally, Williams looked up, out past the audience of 200 or in the direction of the other women who shared the stage with her, each recounting the horrors they had experienced under new, extreme abortion bans. Then it was Williams’s turn to speak.

“Good morning, everyone,” she said. “My name is Shanette.”

On August 19, 2022, she began, clutching the pamphlet, she received a phone call that her daughter was in the hospital. Alarmed, Williams dropped everything and headed to the Piedmont Henry Hospital in Stockbridge, Georgia—about 20 miles south of Downtown Atlanta—where she found her daughter, Amber Nicole Thurman, in the ICU. There, she learned that Thurman had been admitted the day before, after taking medication abortion pills a few days earlier. “It doesn’t matter what happened,” she told her 28-year-old daughter. “Now you’re here, and we’re going to get you the help that you need.”

Thurman needed a dilation and curettage, or D&C—a procedure “that would only take 20 minutes,” Williams recalled the doctors saying. She needed the D&C to clear fetal tissue from her uterus, which had not emptied completely following the abortion—a rare complication for a procedure that works 97 to 99 percent of the time without the need for any interventions. Williams said that she reassured her daughter, telling her she would be OK, even as Thurman cried out, “I’m in pain, I’m in pain!”

“You’re here with professionals, with nurses, with doctors, who are going to give you the care that you need,” Williams recalled saying.

But the medical team didn’t give Thurman the care she needed. Confused about when an abortion might be legally permitted under the state’s six-week abortion ban, they waited too long to perform the D&C—delaying the procedure for 20 hours. By the time they intervened to save Thurman’s life, it was too late.

Williams didn’t know any of this at the time, she explained to the audience in Austin. It would not be until two years later, in September 2024, that she learned from a bombshell ProPublica investigation that her daughter’s death could have been prevented. Her daughter, she discovered, was one of the first women to die following Georgia’s abortion ban. “Now it’s not just my daughter passed—she was murdered,” Williams said. “My baby was murdered by professionals that I trusted, that took an oath to save lives.”

As she spoke, the M-word—murdered—hung heavy in the auditorium, filling the space between the other abortion storytellers, advocates, providers, researchers, and journalists who had packed the amphitheater. She wanted to be very clear, Williams continued: The abortion did not kill her daughter, the mother of a 6-year-old son; the healthcare professionals who were well-equipped to keep her alive but failed to do so did. This, she said, was why she has committed her life to telling her daughter’s story, to ensure that she did not die in vain. It’s the reason she joined Kamala Harris at a campaign event hosted by Oprah Winfrey last September—and the reason she flew to Texas in February to be in community with other storytellers at the first gathering of Abortion in America.

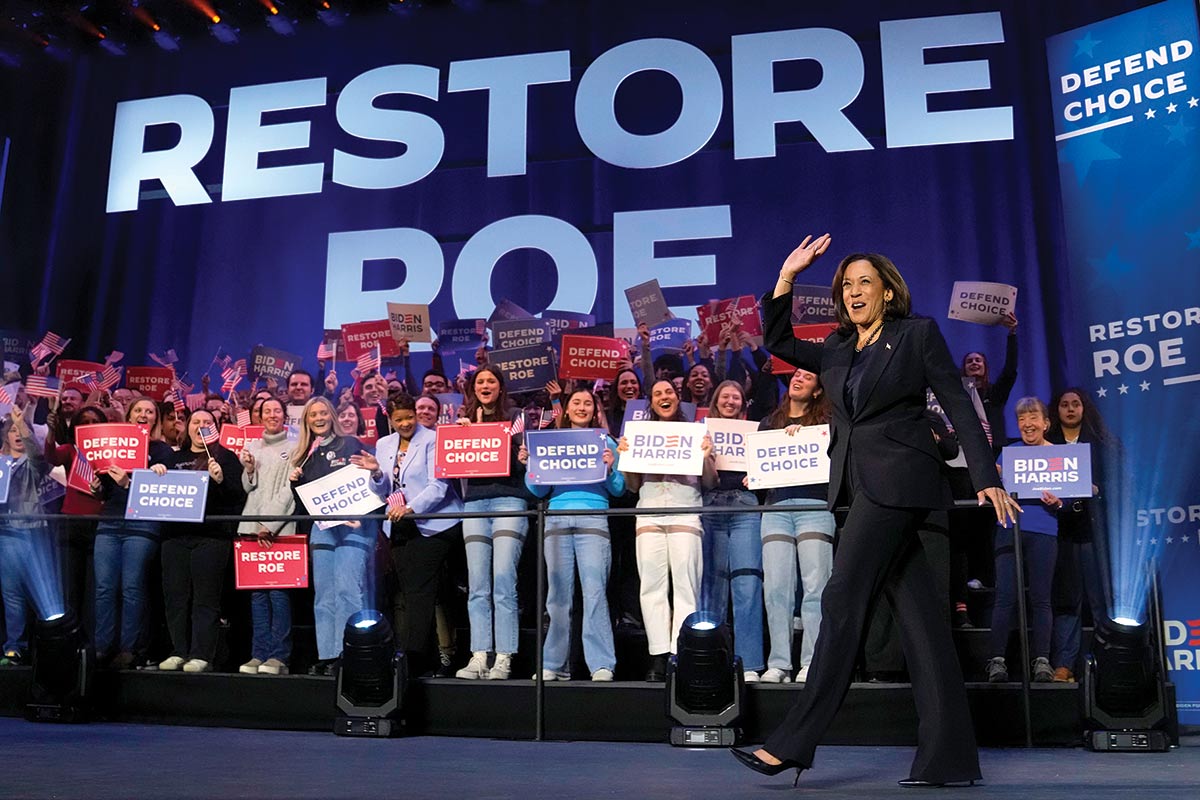

During the 2024 election, after nearly half of all states in the country had banned abortion, Democratic candidates sought to highlight the impact of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization—the Supreme Court case that overturned Roe v. Wade—by amplifying the stories of patients who were denied care in their community as a result of the extreme new anti-abortion laws. Marking a historic first, storytellers spoke on the main stage at the Democratic National Convention (DNC) and at campaign stops across the country. As Tresa Undem, a pollster whose firm has researched the effect of abortion storytelling on public opinion, observed after Williams spoke, “These stories make these bans and the impact of bans real to people. Not intellectual, not theoretical—real. And when they hear these stories, people become informed. And when they are informed, they can do something.”

This idea—that storytelling can move voters who are otherwise unmotivated to take action in support of people in their community—is the driving force behind Abortion in America. The organization was launched by Cecile Richards, the late president of Planned Parenthood, her longtime collaborator Lauren Peterson, and Kaitlyn Joshua. Joshua, who shared her story at the DNC, is a mother and social justice organizer from Louisiana who was denied miscarriage management at around 11 weeks and had to endure the pain of a “spontaneous abortion” without any medical assistance or support.

As Peterson explained to me, Richards had anticipated that Roe would be overturned back in September 2021—after the Supreme Court declined to block SB 8, Texas’s six-week abortion ban, from taking effect. She realized that there needed to be “a concerted effort to lift up the stories of the harm that people had experienced because of abortion bans,” Peterson said. But that winter, when they began to share their idea with people who would be able to amplify these stories, they were told there wasn’t an appetite for it, “because people are burned out and they don’t want to hear it.” The cocreators of AIA didn’t agree: They knew that the number of stories would only grow as vast swaths of the nation went the way Texas had gone.

Nearly two years later, at the end of 2023, as the effects of the abortion bans garnered more media attention, and not long after Richards was diagnosed with glioblastoma, the women regrouped. They decided to start the project and to do so in Louisiana. They began by recording a couple of stories in partnership with Glamour and StoryCorps, and quickly discovered that there was an overwhelming demand for such a project from storytellers—including not just people who have had abortions but also doctors, medical students, and religious leaders who have experiences to share about the importance of this care. And as they initially suspected, there was an audience of people who wanted to hear them.

Abortion in America officially launched in October 2024. But then the election happened, and the candidate with a to-do list lost to the candidate with an enemies’ list. Harris’s defeat was devastating for the abortion storytellers. It wasn’t just the fact of the loss or the prospect of what a Trump presidency would mean for abortion rights, Peterson explained; it was that many of the storytellers had come to rely on the campaign for both community and support. “Cecile would say, ‘It’s like the circus comes through town and then it packs up and leaves.’ What are people supposed to do?”

The morning after the election, as AIA was regrouping, the team decided to have Richards reach out to the storytellers in their network. “We were really worried that people who had shared their stories would feel like it was all for nothing,” Peterson said, especially knowing that, in the states where abortion initiatives had been defeated, such as Florida, the margins had been incredibly narrow (which was remarkable in itself, given state officials’ attempts to sabotage the process).

Deborah Dorbert, a storyteller in Florida, received one of those calls. At 24 weeks pregnant, Dorbert had learned that her unborn child had a fatal condition called Potter syndrome. Because of Florida’s then-15-week abortion ban, however, she had to carry the pregnancy to full term, giving birth to her son Milo only to watch him struggle to breathe for 94 minutes before he died. When Richards called her, however, Dorbert wasn’t demoralized, Peterson said. She wanted to know one thing: “What’s next?”

“This convening is what’s next,” Peterson explained to me between sessions at the AIA conference. “We knew we wanted to bring people together to encourage them to keep going, because this flash point we experienced in this election, when the voices of people who were impacted by bans were so much in the spotlight, needed to not be the end but the beginning.”

It was important to Cecile Richards, who died on January 20, that the gathering be held in Texas. For many of the attendees traveling from out of state, it felt like a revolutionary act to be sitting in a conference center and talking about abortion in the first state to ban abortion. Since the law took effect in 2021, some well-intentioned but misguided activists have suggested writing off places like Texas; everyone should just move to a state where abortion is legal, they say. In fact, organizers in those states argue, we can learn a lot from the people who continue to press for reproductive freedom in places with bans. As Latona Giwa, an abortion doula from Louisiana, reminded AIA attendees, people in these states may not receive an abortion in a clinic, but they still need and should be provided care before and after their abortions (and sometimes during), because it’s a wraparound experience. By focusing solely on the procedure, providers—and activists—are missing the opportunity to improve the full sweep of care for patients.

Storytellers in Southern states are also making inroads with people who previously identified as “pro-life” and are now witnessing on a mass scale the reality that abortion bans undermine maternal healthcare more broadly. That’s because reproductive healthcare is a spectrum that can include pregnancy, miscarriage management, and abortion at different times in a person’s life. This was evident even at the AIA gathering, where some speakers brought their kids with them, while others were visibly pregnant or were there as a support person for a daughter or sister or partner.

“To see how [these women] are understanding how maternal healthcare goes hand in hand with abortion care, and why you literally cannot have one without the other, has been so beautiful,” said Joshua, the AIA cofounder. She was moved “just watching so many women see themselves in everyone else’s stories.”

But as activists have been pointing out since the Dobbs decision, people shouldn’t have to go through a harrowing experience to see these bans for what they are: an effort to control and disempower populations of women and trans people who need and have abortions. When I asked Williams about this, she said, “This could be you. You could be me. That could be your child.”

Williams compared the lack of empathy for people who need access to abortion care to what we saw during the pandemic. For a lot of people, they had to experience getting Covid-19 or witness someone they knew getting it before they could really accept how serious it was. The same has been true for abortion bans.

“Some people think they are above trauma—that ‘this will never happen to me because my child is this way; this will never happen to me because I’m this way,’” Williams said. But as we are witnessing over and over, as the number of people harmed by these bans continues to climb, “it’s just a matter of time” until it happens to you or your loved one, she warned.

As the gathering continued, the critical function of storytelling in the movement for reproductive justice became clearer and sharper: documenting a reality that anti-abortion forces want to keep hidden.

Among the horrors of Williams’s story is that when her daughter died, the truth—that Thurman could easily have been saved, that medical professionals chose not to treat her for 20 hours—was hidden from her for two years. The only reason Williams learned the truth was that ProPublica published its exposé—and the only reason ProPublica was able to do so was that Georgia’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee had reviewed Thurman’s case. But in November 2024, two months after ProPublica published its investigation, the state dismissed all the members of the committee. In a letter to the members (provided to ProPublica by the Georgia Public Health Department), the state said that it was dismissing them because internal reports had been shared with the public and it could not identify “which individual(s) disclosed confidential information.” As a result, “effective immediately the current MMRC is disbanded, and all member seats will be filled through a new application process.”

Georgia is not the only state to take regressive action to prevent the public from understanding the extent of the maternal mortality crisis in the wake of extreme abortion bans. Texas’s Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Review Committee announced in September, after ProPublica’s investigation and after the state’s own report found a surge in pregnancy-related deaths in 2020 and 2021, disproportionately among Black women, that it would skip reviewing pregnancy-related deaths from 2022 and 2023. As The Texas Tribune reported, the state has previously skipped years “to try to catch up,” but this particular period represents a glaring omission considering that it covers the first two years following the implementation of SB 8, during which we already know that at least three women died after doctors delayed providing abortion care.

When I asked Williams what it will mean for families like hers to not have maternal deaths investigated by state health departments, she explained that, were it not for a person on Georgia’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee who “had a heart,” she would never have learned the truth about her daughter’s death. “For a board that I never knew anything about in the state of Georgia—never heard of it, never anything—it was my child,” she said. “People don’t talk about God being real, but he is, whoever that God is to you. But somebody had a conviction that said, ‘I have to tell this.’ We were never supposed to know.”

Now that the committee is effectively being gagged, Williams said she hopes that doctors and others will come forward—because “how many other cases will we never know about?”

Because anti-abortion lawmakers are not only banning lifesaving care for patients but also taking steps to hide the consequences of the laws they’ve championed, it’s difficult to imagine what “winning” will mean in the future. “It won’t necessarily be with the Legislature or be on the city level or even the state level,” Joshua explained. But, she advised, it can happen within our communities.

For Joshua, the answer begins with two essential questions: “How can we win over narratives?” and how can we “help people [make] a decision on abortion care that is well-informed?” It is in the service of finding solutions to these questions that Joshua cofounded Abortion in America—work to which she brings an extensive background in organizing around environmental racism, labor, and voting rights reform, among other issues. All of these issues touch the lives of Black people in Louisiana, where she lives.

“The very same people who are deeply impacted by environmental racism are also the same people who cannot tap into adequate healthcare when they need it the most…. All of it goes hand in hand,” she explained. “When you really take a step back and see the bigger picture, it puts things in perspective, in terms of the ways in which we can be working together.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The challenge is that some forms of discrimination can persist even when hearts and minds change after hearing abortion stories.

Despite being the majority of people who have abortions in the United States, people of color and low-income people are often underrepresented as storytellers, as are transgender and gender-nonconforming people. A 2023 Guttmacher Institute study found that nonheterosexual people represent 16 percent of people who have abortions. We are witnessing a shift in recent years, in large part as a result of the work of Renee Bracey Sherman (with whom I cowrote a book titled Liberating Abortion: Claiming Our History, Sharing Our Stories, and Building the Reproductive Future We Deserve) through her organization We Testify, which supports the leadership of storytellers who are underrepresented in reproductive rights spaces. But far too often, it’s married, well-off white women who have had medically necessary abortions who are the face of the movement, when a lot of the medical neglect happening today was happening to people of color while Roe was still the law of the land. And when the stories of people of color are shared, there is not enough time to go into the countless factors that have contributed to their decision to have an abortion—whether it’s medically necessary or simply their choice. Instead, their stories are flattened or tidied up, losing their power to not only disrupt the right’s fearmongering but also to dismantle systemic oppression once and for all.

Shanette Williams told me that before her daughter’s death, she didn’t really vote or engage much in politics. After connecting with Kamala Harris’s team, which she said has continued to check in on her even after the election, she sees electoral politics differently. But even as she has begun participating in elections, she is clear that these issues will not be solved by one person.

“It takes everybody,” Williams said. After the election, there was a lot of blame put on the Harris campaign for what she did or didn’t do for various people, “but she’s only one person… and racism is real. It’s not just racism among whites and Blacks, it’s among Blacks and Blacks and among women—we hurt ourselves.”

Throughout the AIA conference, amid the coos of babies swaddled against their parents and the laughter of toddlers playing in the back of the theater, panelists were asked what gives them hope these days. Most often, people responded that it was the other storytellers or providers in the room who were keeping them going. One provider was honest about how she is struggling, speaking to the despair so many are feeling. “It’s like, what is the point? Why am I trying to take care of patients who don’t vote, or vote for Trump—or when half the country, it feels like, are against us and would prefer that we just be in jail? So I’m really struggling. But it’s really great to be here and have the community.”

Latona Giwa, the abortion doula, said that the elders give her hope—“folks who can say, ‘We’ve been through this, we’ve been doing this, and we’re gonna keep doing it.’”

For me, it was Shanette Williams. She is showing her grandson—and the world—what it means to love and what it means to fight.

“If we stop [sharing our stories], they’ve won. If we stop, my baby’s death was in vain,” Williams told me. “I’m not stopping.”