This is the last of three slide shows detailing the lives and legacies of the fifty most influential progressives of the twentieth century. Here, read Peter Dreier’s introduction to the series. Here are the first and second slide shows. Click here to nominate the American progressives you think made the biggest difference in the twentieth century—and the activists, advocates and politicians who are already defining the twenty-first.

King helped change America’s conscience, not only about civil rights but also about economic justice, poverty and war. As an inexperienced young pastor in Montgomery, Alabama, King was reluctantly thrust into the leadership of the bus boycott. During the 382-day boycott, King was arrested and abused and his home was bombed, but he emerged as a national figure and honed his leadership skills. In 1957 he helped launch the SCLC to spread the civil rights crusade to other cities. He helped lead local campaigns in Selma, Birmingham and other cities, and sought to keep the fractious civil rights movement together, including the NAACP, Urban League, SNCC, CORE and SCLC. Between 1957 and 1968 King traveled more than 6 million miles, spoke more than 2,500 times and was arrested at least twenty times while preaching the gospel of nonviolence. Today we view King as something of a saint; his birthday is a national holiday and his name adorns schools and street signs. But in his day the establishment considered King a dangerous troublemaker. He was harassed by the FBI and vilified in the media. The struggle for civil rights radicalized him into a fighter for economic and social justice. During the 1960s King became increasingly committed to building bridges between the civil rights and labor movements. He was in Memphis in 1968 to support striking sanitation workers when he was assassinated. In 1964, at 35, King was the youngest man to have received the Nobel Peace Prize. Some civil rights activists worried that his opposition to the Vietnam War, announced in 1967, would create a backlash against civil rights, but instead it helped turned the tide of public opinion against the war.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Let Justice Roll Down by Martin Luther King Jr.

Further Reading:

Why We Can’t Wait by Martin Luther King Jr.

Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference by David J. Garrow.

Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954-63 by Taylor Branch.

Credit: AP Images

Rustin was one of the nation’s most talented organizers, typically working behind the scenes, as an aide to Muste, Randolph and King, in large part because they feared that his homosexuality would stigmatize their causes and organizations. Randolph appointed him to lead the youth wing of the 1941 march on Washington movement. Rustin was upset when Randolph called off the march after FDR issued an executive order banning racial discrimination in the defense industries. Rustin then began a series of organizing jobs in the peace movement, honing his skills with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the American Friends Service Committee, the Socialist Party and the War Resisters League. In 1947 he began organizing a series of nonviolent acts of civil disobedience in the South and border states to provoke a challenge to Jim Crow practices in interstate transportation. Between 1947 and 1952 Rustin traveled to India and Africa to learn more about nonviolence and the Gandhian independence movement. Rustin spent time in Montgomery and Birmingham advising King about nonviolent tactics. Coming full circle, Randolph named him chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, diplomatically bringing together fractious civil rights leaders and organizations.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Letter to the Editor: Human Detente by Bayard Rustin.

Further Reading:

From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights Movement by Bayard Rustin.

Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin by John D’Emilio.

Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen by Jervis Anderson.

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

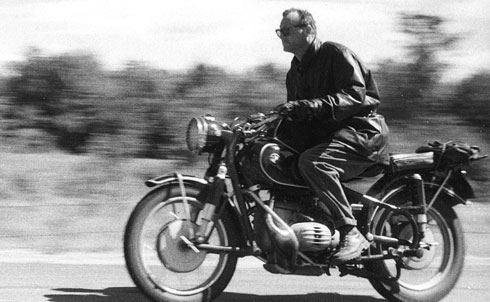

In the 1950s, when most social scientists were celebrating America’s postwar prosperity, Mills, a Columbia University sociologist, was warning about the dangers of the concentration of wealth and power in what he called, in his 1956 book of the same name, “the power elite.” He also warned about the US attitude toward Cuba in Listen, Yankee. Shunned by most fellow sociologists, his ideas—outlined in books, scholarly journals and many magazine articles—became popular among 1960s activists. Mills’s then-radical notion that big business, the military and government can be too closely connected is now conventional wisdom.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Balance of Blame by C. Wright Mills.

Further Reading:

The Power Elite by C. Wright Mills.

Radical Ambition: C. Wright Mills, the Left, and American Social Thought by Daniel Geary.

Credit: Yaroslava Surmach Mills

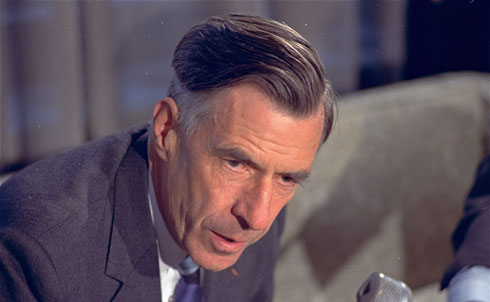

Galbraith was the century’s leading progressive American economist. His many books and articles helped popularize Keynesian ideas, especially The Affluent Society (1958), which coined the title phrase but also warned about the widening gap between private wealth and public squalor. In The New Industrial State (1967), the Harvard professor criticized the concentration of corporate power and recommended stronger government regulations. Active in politics, he served in the administrations of FDR, Truman, JFK and LBJ, including as Kennedy’s ambassador to India.

Further Reading:

The Affluent Society and The New Industrial State by John Kenneth Galbraith.

John Kenneth Galbraith: His Life, His Politics, His Economics by Richard Parker.

Credit: AP Images

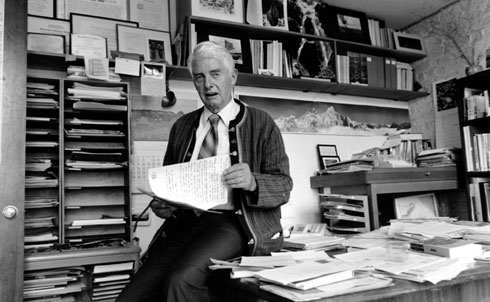

Brower, who began his career as a world-class mountaineer, was a pioneer of the modern environmental movement. He served as the Sierra Club’s first executive director from 1952 to 1969, expanding the group’s membership from 7,000 to 77,000 members. He led campaigns to establish ten new national parks and seashores and to stop dams in Dinosaur National Monument and Grand Canyon National Park. He was instrumental in gaining passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, which protects millions of acres of public lands in pristine condition. He founded Friends of the Earth and then the League of Conservation Voters, mobilizing environmentalists for political action. In 1982 he founded Earth Island Institute to support environmental projects around the world.

Further Reading:

Wilderness: America’s Living Heritage by David Brower.

Encounters with the Archdruid by John McPhee.

Credit: AP Images

Seeger wrote or popularized “We Shall Overcome,” “Turn, Turn, Turn,” “If I Had a Hammer,” “Guantanamera,” “Wimoweh,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” and other songs that inspired people to take action. On his own and as a member of the Almanac Singers and the Weavers (which had several top-selling hits, including “Good Night, Irene,” despite their opposition to commercialism), Seeger sang for unions, civil rights and antiwar groups and other human rights causes in the United States and around the world. He introduced Americans to the music of other cultures and catalyzed the “folk revival” of the late 1950s and ’60s. He was a founder of the Newport Folk Festival and Sing Out! magazine. He was also an environmental pioneer, founding the sloop Clearwater and raising consciousness and money to push government to clean up the Hudson River and other waterways.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Songbag by Pete Seeger.

Further Reading:

Everybody Says Freedom: A History of the Civil Rights Movement in Songs and Pictures by Pete Seeger.

How Can I Keep From Singing? The Ballad of Pete Seeger by David King Dunaway.’

"To Everything There Is A Season": Pete Seeger and the Power of Song by Allan M. Winkler.

Credit: New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

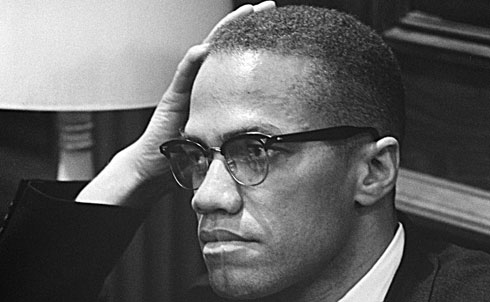

A onetime street hustler involved in drugs, prostitution and gambling, Malcolm Little converted to Islam while in prison and, upon his release, became a leading minister of the Nation of Islam, a forceful advocate for black pride and a harsh critic of white racism. As Malcolm X, he inspired the Black Power movement, which competed with the integrationist wing of the civil rights movement for the loyalty of African-Americans, and wrote (with Alex Haley) the bestselling The Autobiography of Malcolm X. His father—an outspoken Baptist preacher and avid supporter of Black Nationalist leader Marcus Garvey—faced death threats from the white supremacist organization Black Legion and was killed in 1931. As a popular minister for the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X preached a form of black separatism and self-help. One of his recruits was boxer Muhammad Ali. In 1964, disillusioned by Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad’s behavior, Malcolm X left the organization. That year, he traveled to Mecca and, in his words, met “all races, all colors, blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans in true brotherhood!” When he returned to the United States he had a new view of racial integration. He was shot and killed on February 21, 1965, after giving a speech in Manhattan’s Audubon Ballroom. Many suspect that Elijah Muhammad had a hand in his murder.

Further Reading:

The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention by Manning Marrable.

Credit: U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection (Library of Congress)

Her book The Feminine Mystique (1963) helped change American attitudes toward women’s equality, popularized the phrase “sexism” and catalyzed the modern feminist movement. In the 1940s and 1950s she worked as a left-wing labor journalist before focusing her writing and activism on women’s rights. She co-founded the National Organization for Women in 1966 and the National Women’s Political Caucus (along with Gloria Steinem, Fannie Lou Hamer, Bella Abzug and Shirley Chisholm) in 1971.

Further Reading:

The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan.

Betty Friedan and the Making of "The Feminine Mystique": The American Left, the Cold War, and Modern Feminism by Daniel Horowitz.

Credit: AP Images

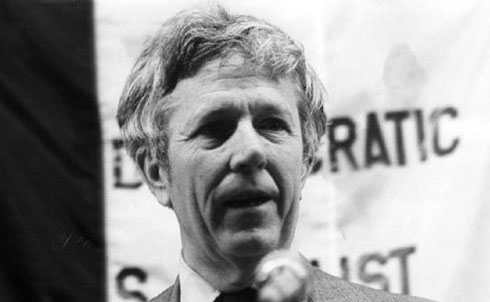

His book The Other America (1962) exposed Americans to the reality of poverty in their midst. In his 20s, Harrington joined Dorothy Day’s Catholic Workers movement, lived among the poor at the Catholic Worker house and edited the Catholic Worker from 1951 to 1953. The Other America catapulted Harrington into the national spotlight. He became an adviser to LBJ’s “war on poverty” and a popular lecturer on college campuses, at union halls and academic conferences and before religious congregations. Inheriting Norman Thomas’s mantle, he was America’s leading socialist thinker, writer and speaker for four decades, providing ideas to King, Reuther, Robert and Ted Kennedy and other leaders. Harrington wrote fifteen other books on social issues and helped build bridges between left intellectuals and academics and the civil rights and labor movements. He encouraged activists to promote “the left wing of the possible.” He founded Democratic Socialists of America, which remains the nation’s largest socialist organization.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Myth That Was Real by Michael Harrington.

Further Reading:

The Other America: Poverty In the United States by Michael Harrington.

The Other American: The Life of Michael Harrington by Maurice Isserman.

Building on his experiences as a farmworker and community organizer in the barrios of Oakland and Los Angeles, Chavez did what many thought impossible—organize the most vulnerable Americans, immigrant farmworkers, into a successful union, improving conditions for California’s lettuce and grape pickers. Founded in 1960s, the United Farm Workers pioneered the use of consumer boycotts, enlisting other unions, churches and students to join in a nationwide boycott of nonunion grapes, wine and lettuce. Chavez led demonstrations, voter registration drives, fasts, boycotts and other nonviolent protests to gain public support. The UFW won a campaign to enact California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which Governor Jerry Brown signed into law in 1975, giving farmworkers collective bargaining rights they lacked (and still lack) under federal labor law. The UFW inspired and trained several generations of organizers who remain active in today’s progressive movement.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

The Farm Workers’ Next Battle by Cesar Chavez.

Further Reading:

"The Mexican American and the Church" by Cesar Chavez.

Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa by Jacques E. Levy.

The Union of Their Dreams: Power, Hope, and Struggle in Cesar Chavez’s Farm Workers Movement by Miriam Pawel.

Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement by Marshall Ganz.

Credit: AP Images

Milk was elected to San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors in 1977, making him the first openly gay elected official in California and the most visible gay politician in the country. He moved to San Francisco in 1972 and set up a camera shop in the city’s Castro district, quickly getting involved in local politics. Called “the mayor of Castro Street,” Milk was a charismatic gay rights activist who built alliances with other constituencies, including neighborhood and tenants’ groups. He became an ally of the labor movement by getting gay bars to remove Coors beer, which unions were boycotting for Coors’s opposition to union organizing in its breweries and the Coors family’s support for right-wing causes. As city supervisor, he orchestrated passage of a law that prohibited discrimination in housing and employment based on sexual orientation. In 1978 he led the opposition to a statewide ballot measure (the Briggs initiative) to ban homosexuals from jobs as schoolteachers. On November 27, 1978, he was killed by Dan White, a disgruntled former city supervisor who disagreed with Milk and Mayor George Moscone, whom he also assassinated that day.

Further Reading:

The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk by Randy Shilts.

Credit: AP Images

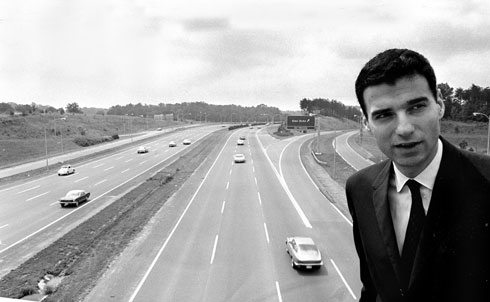

Since 1965, when he published his exposé of the auto industry, Unsafe at Any Speed, Nader has inspired, educated and mobilized millions of Americans to fight for a better environment, safer consumer products, safer workplaces and a more accountable government. Thanks to Nader, our cars are safer, our air and water are cleaner and our food is healthier. He raised awareness about the dangers of nuclear power and helped stop the construction of nuclear power plants. Nader played an important role in milestones such as the Freedom of Information Act, the Clean Air Act, the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Superfund program, the Environmental Protection Act, the Consumer Product Safety Commission and the Occupational Safety and Health Act. Nader built a network of organizations to research and lobby against corporate abuse, training tens of thousands of college students and others in the skills of citizen activism. He has written many books, all focusing on how citizens can make America more democratic. During the 1970s and ’80s Nader topped most polls as the nation’s most trusted person. He ran for president four times, most controversially in 2000, when as a Green Party candidate he won votes in Florida that may have cost Democrat Al Gore the election.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

How to Curb Corporate Power by Ralph Nader.

Fashion or Safety by Ralph Nader.

Further Reading:

Ralph Nader: A Biography by Patricia Cronin Marcello.

Credit: AP Images

Steinem helped popularize feminist ideas as a writer and activist. Her 1969 article “After Black Power, Women’s Liberation” helped establish her as a national spokeswoman for the women’s liberation movement and for reproductive rights. In 1970 she led the Women’s Strike for Equality march in New York along with Betty Friedan and Bella Abzug. In 1972 she founded Ms. magazine, which became the leading feminist publication. Her frequent articles and appearances on TV and at rallies made her feminism’s most prominent public figure. She co-founded the National Women’s Political Caucus, the Ms. Foundation for Women, Choice USA, the Women’s Media Center and the Coalition of Labor Union Women. In 1984 she was arrested, along with Coretta Scott King, more than twenty members of Congress and other activists, for protesting apartheid in South Africa. She also joined protests opposing the Gulf War in 1991 and the Iraq War in 2003.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Why I’m Not Running For President by Gloria Steinem.

Further Reading:

"After Black Power, Women’s Liberation" by Gloria Steinem.

Gloria Steinem: Her Passions, Politics, and Mystique by Sydney Ladensohn Stern.

Credit: AP Images

Hayden was a founder of Students for a Democratic Society in 1960 and wrote its Port Huron Statement, a manifesto of the postwar baby boom generation. He worked as a community organizer in Newark and helped link student activists to the civil rights movement and later the antiwar movement. He made several high-profile trips to Cambodia and North Vietnam to challenge US military involvement in Southeast Asia. Hayden was the first leading 1960s radical activist to run for major political office, challenging Senator John Tunney of California in the Democratic primary of 1976. He was later elected to the California legislature, where he served for eighteen years as an environmental and consumer advocate, while continuing his antiwar activism, gang intervention work and writing for The Nation and other publications. He is the author of seventeen books.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

Progressives for Obama by Tom Hayden.

Unfinished Business by Tom Hayden.

Further Reading:

The Port Huron Statement by Tom Hayden.

Reunion by Tom Hayden.

Democracy in the Streets by James Miller.

Credit: AP Images

As a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988, Jackson, a Baptist minister and aide to King, popularized the idea of a progressive multiracial and socially diverse “rainbow coalition.” After the 1965 march to Selma, Jackson moved to Chicago to head the city’s SCLC office and to start Operation Breadbasket and later Operation PUSH, which pioneered the use of boycotts and other pressure tactics to get private corporations to hire African-Americans and do business with black-owned firms. In his second bid for the White House, Jackson won seven primaries and four caucuses. He also gained influence by arranging exchanges or releases of US political prisoners in Syria, Cuba and Belgrade.

From The Nation‘s Archives:

For Jesse Jackson and His Presidency by The Editors.

Further Reading:

Legal Lynching: The Death Penalty and America’s Future by Jesse Jackson.

Jesse: The Life and Pilgrimage of Jesse Jackson by Marshall Frady.

Credit: John H. White

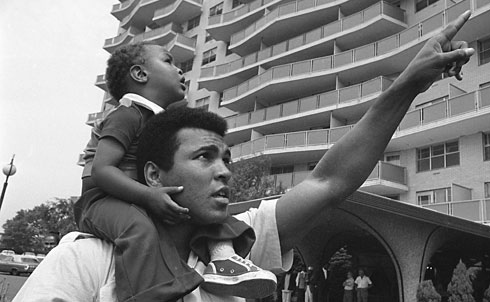

Born Cassius Clay in Louisville, Ali became an Olympic gold medal boxer in 1960, three-time heavyweight champion of the world, a highly visible opponent of the Vietnam War and a symbol of pride for African-Americans and Africans. He called himself “the greatest,” composed poems that predicted the round in which he’d knock out his next opponent and told reporters that he could “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.” In 1964, soon after winning the heavyweight championship, he revealed that he was a member of the Nation of Islam, changing his name. Two years later, Ali refused to be drafted into the military, stating that his religious beliefs prevented him from fighting in Vietnam. He said, “No Vietnamese ever called me nigger,” a statement suggesting that US involvement in Southeast Asia was a form of colonialism and racism. The government denied his claim for conscientious objector status, and he was arrested for refusing induction. He was stripped of his heavyweight title, and his boxing license was suspended. He reclaimed the crown in 1974 by beating George Foreman in the so-called Rumble in the Jungle. For his boxing skills and political courage, he was among the most recognized people in the world in the 1960s and ’70s.

Further Reading:

The Greatest: My Own Story by Muhammad Ali.

King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero by David Remnick.

Credit: AP Images

King was at the top of women’s tennis for nearly two decades. She won her first Wimbledon singles title in 1966, piled up dozens of singles and doubles titles before retiring in 1984 and was ranked number one in the world for five years. She founded the Women’s Tennis Association, the Women’s Sports Foundation and WomenSports magazine. She championed Title IX legislation, which equalized opportunities for women on and off the playing field. In 1972 she signed a controversial statement, published in Ms., that she had had an abortion, putting her on the front lines of the battle for reproductive rights. In 1972 she became the first woman to be named Sports Illustrated “Sportsperson of the Year.” In 1981 she was the first major female professional athlete to come out as a lesbian. She has consistently spoken out for women and their right to earn comparable money in tennis and other sports.

Further Reading:

Pressure Is a Privilege: Lessons I’ve Learned from Life and the Battle of the Sexes by Billie Jean King.

A Necessary Spectacle: Billie Jean King, Bobby Riggs, and the Tennis Match That Leveled the Game by Selena Roberts.

Credit: Michael Cole/Courtesy of HBO

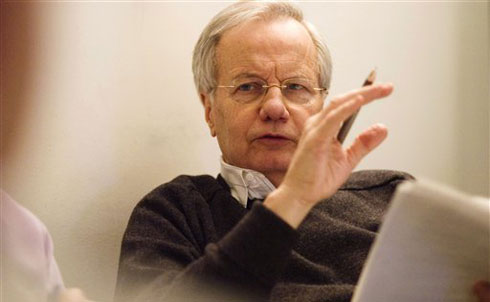

Moyers served as JFK’s deputy director of the Peace Corps, LBJ’s press secretary, publisher of Newsday and commentator on CBS, but he had his greatest influence as a documentary filmmaker and interviewer on PBS for three decades before retiring earlier this year. Following in the footsteps of broadcaster Edward R. Murrow, Moyers used TV as a tool to expose political and corporate wrongdoing and tell stories about ordinary people working together for justice. Like Studs Terkel, he introduced America to great thinkers, activists and everyday heroes typically ignored by mainstream media. Reflecting the populism of his humble Texas roots and the progressive convictions of his religious training (he is an ordained Baptist minister), Moyers produced dozens of hard-hitting investigative documentaries revealing corporate abuse of workers and consumers, the corrupting influence of money in politics, the dangers of the religious right, the attacks on scientists over global warming, the power of community and union organizing and many other topics. Trade Secrets (2001) uncovered the chemical industry’s poisoning of American workers, consumers and communities. Buying the War (2007) investigated the media’s failure to report the Bush administration’s propaganda about weapons of mass destruction and other lies that led to the war in Iraq. A gifted storyteller, Moyers, on the air and in the pages of The Nation and elsewhere, roared with a combination of outrage and decency, exposing abuse and celebrating the country’s history of activism.

From The Nation:

The Moyers Legacy by The Editors.

Further Reading:

Moyers on America: A Journalist and His Times by Bill Moyers.

Moyers on Democracy by Bill Moyers.

In twenty books and hundreds of articles in mainstream newspapers and magazines as well as progressive outlets, she has popularized ideas about women’s rights, poverty and class inequality and America’s healthcare crisis. Beginning with The American Health Empire (1971), Complaints and Disorders: The Sexual Politics of Sickness (1973) and other books, she exposed the way the healthcare system discriminates against women and the poor, helping efforts to change the practices of hospitals, medical schools and physicians. In The Mean Season (1987), Fear of Falling (1989), The Worst Years of Our Lives (1990) and Bait and Switch (2005), she exposed the downside of America’s class system for the poor and the middle class. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America (2001), a bestselling first-person account of her yearlong sojourn in low-wage jobs, documented the hardships facing the working poor and helped energize the burgeoning “living wage” movement. She is co-chair of Democratic Socialists of America.

From The Nation:

The Communist Manifesto Turns 160 by Barbara Ehrenreich.

Further Reading:

Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich.

Credit: Sigrid Estrada

In the tradition of earlier muckraking journalists, Moore has used his biting wit, eye for human foibles, anger at injustice, faith in the common sense of ordinary people and skills as a filmmaker, author and public speaker to draw widespread attention to some of America’s most chronic problems. His first film, the low-budget documentary Roger & Me (1989), examined the tragic human consequences of General Motors’ decision to close its factory in Flint (Moore’s hometown) and export the jobs to Mexico. The Big One (1997) examined corporate America’s large-scale layoffs during a period of record profits, focusing on Nike’s decision to outsource its shoe production to Indonesia. His documentaries in the twenty-first century have explored America’s love affair with guns and violence (the Academy Award–winning Bowling for Columbine), the links between the families of George W. Bush and Osama bin Laden in the aftermath of September 11 (Fahrenheit 9/11), healthcare reform (Sicko) and the financial crisis and the political influence of Wall Street (Capitalism: A Love Story). Moore also directed and hosted two TV news magazine shows—TV Nation (1994–95) and The Awful Truth (1999–2000)—that focused on controversial topics other shows avoided. The author of several books of political satire—including Downsize This! (1996), Stupid White Men (2001) and Dude, Where’s My Country? (2003)—Moore is a frequent commentator on TV talk-shows and regularly speaks at rallies and events to help build a movement for economic and social justice.

From The Nation:

America’s Teacher, Naomi Klein in conversation with Michael Moore.

Further Reading:

Stupid White Men, Downsize This! and Dude, Where’s My Country? by Michael Moore.

Credit: AP Images

Peter Dreier’s list of most influential progressives isn’t intended to be complete—we need you to help us fill out the picture! Now that all 50 of the progressives Dreier selected have appeared online, we ask you to nominate the American progressives you think made the biggest difference in the twentieth century—and the activists, advocates and politicians who are already defining the twenty-first. Submit your picks here.

Credit: AP Images