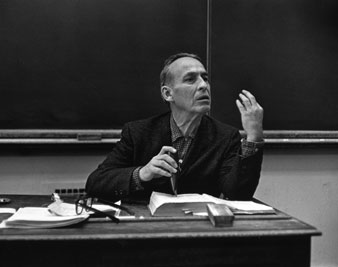

LESLIE STRAUSS TRAVISNorman Maclean teaching at the University of Chicago, 1970

LESLIE STRAUSS TRAVISNorman Maclean teaching at the University of Chicago, 1970

I know it’s uncool to admit an enthusiasm based in part on biography–it seems so louche–but I feel as if I’ve been following in Norman Maclean’s footsteps much of my life. Like him, I was born in Iowa and left at a young age; like him, I lived a portion of my early life in Missoula, Montana. I have, like him, worked as a fire lookout in the West, with a view of “more mountains in all directions than I was ever to see again–oceans of mountains,” as Maclean wrote in “USFS 1919: The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky”; and I have fished rivers and creeks sparkling with the movement of cutthroat trout, per his instructions. Maclean spent his life attempting to reconcile his love of Chicago with his love of Montana, as I have mine for New York and New Mexico.

About once a year I still reach for my dog-eared copy of A River Runs Through It and Other Stories, and it never loses its power or its mystery. No other book I know has more evangelists, as it would have to, being a collection of two novellas and a story published by a university press, and now with beyond a million copies in print. My deep connection with the book–with the leisurely rhythms of the sentences, which matched the rhythms of my childhood spent fishing with my brother–had already blurred the distinction between life and literature, although of course I never suspected the book would one day prove prophetic. But it did twelve years ago, when, just as Norman loses his brother Paul to a violent death, a brother he loved but did not understand and could not help, I lost my own brother, at the age of 22, to a suicide with a semiautomatic rifle.

I’m not sure any sense can be made of his action, and anyway the details are not my concern here. But I do often find myself in the same position as Norman and his father, asking unanswerable questions, searching for something, some bit of redeeming truth to reckon with. There is a scene near the end of the title novella, in which the two of them talk about their son and brother.

“Do you think I could have helped him?” Norman’s father asks.

“Do you think I could have helped him?” Norman answers.

They stand silently, each of them waiting for an answer they know will never come. “How can a question be answered that asks a lifetime of questions?” Norman wonders.

Maclean would report receiving letters from people like me during the fourteen years he had left after the book was published in 1976. And he would go to his grave secure in the knowledge that anyone who’d fished with a fly in the Rockies and read his novella on the how and why of it believed it to be the best such manual on the art ever written–a remarkable feat for a piece of prose that also stands as a masterwork in the art of tragic writing.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Maclean, who was born in 1902, learned to write from his father, a Presbyterian minister who taught his son at home until he was 10. The morning was divided into three hourlong periods, during each of which Norman gave a fifteen-minute recitation. His father’s highest ideals were economy and precision with the English language; he wanted his son to grow up as an authentic American, with a mastery of the American written word. In the afternoons Maclean fished and played in the woods and learned how to be tough, toughness being one of the chief preoccupations of his late-life writing.

As a teenager he worked summers with the US Forest Service, then less than two decades old, an opportunity he was afforded because able-bodied woodsmen had gone to fight in World War I. In 1920 he went east to college at Dartmouth, to study English. When he finished, he returned home to Montana and worked again briefly in the mountains of his youth. It was a moment that divided his past and his future forever. He often looked back at a career that might have been–a career in the woods, in logging camps, fighting fires and packing mules and playing cribbage in the bunkhouse. Instead he went to the University of Chicago, where he earned his doctorate and later held the post of William Rainey Harper Professor of English. He taught there more than forty years, mostly Shakespeare and the Romantic poets, and decamped from Hyde Park for Montana each summer, where he spent three months at his family’s cabin on Seeley Lake.

His career is one of the strangest in American letters. Maclean began to write fiction only upon retirement, when he had “reached his biblical allotment of three score years and ten,” as he liked to put it. He claimed he picked up his pen at the urging of his two children, Jean and John, who wished to know what he and the world were like when he was young. The initial result, two years in the making, was A River Runs Through It, which came out of nowhere, the first and for a long time the only book of fiction to be published by the University of Chicago Press. The book’s two novellas and short story (“Logging and Pimping and ‘Your Pal, Jim'”) are set in Montana in the early twentieth century, all heavily auto- biographical–tales he playfully called “Western stories with trees in them for children, experts, scholars, wives of scholars, and scholars who are poets.”

The book was short listed for a Pulitzer in 1977, although the judges that year deemed no book worthy of the award and abstained from offering a prize in fiction. In later years Maclean had cause to wonder if the judges maybe didn’t like trees. That’s the excuse one New York publisher offered in rejecting the book–“these stories have trees in them”–a fact that gave Maclean great satisfaction in his final years. After the smash success of the book, an editor at Knopf, which had rejected the manuscript, wrote to inquire whether the house might have a look at Maclean’s second novel, on which he was rumored to be at work.

“I don’t know how this ever happened, but this fell right into my hands,” Maclean says in an interview reprinted in The Norman Maclean Reader, the capstone to his peculiar career, which contains an unfinished book manuscript, several essays and interviews and a selection of unpublished letters. “So I wrote a letter…. I can remember the last paragraph: ‘If it should ever happen that the world comes to a place when Alfred A. Knopf is the only publishing company left and I am the only author, then that will be the end of the world of books.'” It seems in some way appropriate that he did not live to see his final book, Young Men and Fire, win the National Book Critics Circle Award for nonfiction, in 1992, although his acceptance speech no doubt would have been one to remember, if he’d chosen to give it. Having begun to write so late in life, he was not angling for prizes.

It’s not as if Maclean didn’t know his stories were strange. He often said he wrote them in part so the world would know of what artistry men and women were capable in the woods of his youth, before helicopters and chain saws rendered obsolete the ancient skills of packing with mules and felling trees with crosscut saws. Artistry, specifically artistry with one’s hands, was for him among life’s most refined achievements. As he says in the opening pages of “A River Runs Through It,” “all good things–trout as well as eternal salvation–come by grace and grace comes by art and art does not come easy.” Among the many things that make the novella charmingly weird is how it begins with a long piece of expository prose on how to cast a fly with a four-and-a-half-ounce rod–an opening almost Modernist in its diffidence to the rituals of storytelling, as if begging for attrition from the uncommitted. Once he is assured you are with him, however, he then shows you, as the story progresses, how to make more specialized casts, how to read a river and see where the trout live, how to choose the correct fly to entice them and, finally, how to land a big fish once you’ve hooked it. All the while, he is mingling comedy and tragedy, and making metaphors of surpassing beauty, often while hinting at his brother’s coming doom:

As the heat mirages on the river in front of me danced with and through each other, I could feel patterns from my own life joining them. It was here, while waiting for my brother, that I started this story, although, of course, at the time I did not know that stories of life are more often like rivers than books. But I knew a story had begun, perhaps long ago near the sound of water. And I sensed that ahead I would meet something that would never erode so there would be a sharp turn, deep circles, a deposit, and quietness.

In a story in which every piece is irregular and every piece fits with every other, it is no accident that the final line is this: “I am haunted by waters.” If, as Chekhov said, the object is not to paint a picture of the moon in the sky but in a piece of broken glass, Maclean had learned from his masters and, being tough, picked up the jagged shard and used it as a knife.

If “A River Runs Through It” lightly fictionalized Maclean’s life story, Young Men and Fire offered him a chance to explore the other life he might have lived, the life of a Forest Service firefighter. In “Black Ghost,” which appears again in the Reader, having served as the prologue to Young Men and Fire, Maclean recounts his arrival at a scene of conflagration along the Missouri River in August 1949, with the fire still burning in stump holes and scattered trees. The smell and the look of the gulch in which the fire blew up haunted him the rest of his life. The book is, in one sense, the story of an unforeseen disaster, in which smoke jumpers accustomed to unifying earth, wind and fire found themselves overwhelmed by that final element, which they could not outrun. It is also, as Maclean put it, a story in search of itself as a story–or, to say it another way, a tragedy in search of a tragedian. He spent most of the last fourteen years of his life on it, and the typescript remained unfinished at his death.

His description of the gulch after the fire offers a sense of how he managed a poetically laconic style that was also occasionally religious in tone, suffused with images he absorbed in his youth as the child of a preacher:

Nearly half a mile away the [rescue] crew could hear Hellman shouting for water. In the valley of ashes there was another sound–the occasional explosion of a dead tree that would blow to pieces when its resin became so hot it passed the point of ignition. There was little left alive to be frightened by the explosions. The rattlesnakes were dead or swimming the Missouri. The deer were also dead or swimming or euphoric. Mice and moles came out of their holes and, forgetting where their holes were, ran into the fire. Following the explosion that sent the moles and ashes running, a tree burst into flames that almost immediately died. Then the ashes settled down again to rest until they rose in clouds when the crew passed by.

“In the valley of ashes”–the phrase reminiscent of The Great Gatsby–is in this instance meant to evoke the biblical valley of the shadow of death, as indeed Mann Gulch appeared to be and smelled on that August afternoon when a fire whirl caught thirteen men as they ran for their lives uphill. Maclean also returns repeatedly to a version of the event as a kind of Passion play, with Stations of the Cross scattered up the hill, marked now by literal crosses where each of the dead men fell, monuments to their unimaginable end. With dogged precision he taught himself the latest wildfire science, coaxed a friend to help him mark time on the hill and read and reread the official report on the fire, with its details about the recollections of the three survivors, two of whom he led back to the scene to revisit their close encounter with death. The smoke jumpers’ foreman, Wag Dodge, had lit an escape fire and lay down in its ashes as the larger fire whirl passed over his men: he tried in vain to persuade them to join him, the only hope for survival most of them had, though none of them listened. He would die five years later, haunted by his inability to show his men the way to their afterlife beyond the fire. Although Maclean never says so explicitly, Dodge resembles a kind of Jesus figure, misunderstood in his message at the moment it counted most for the world, that world for Dodge consisting of young men running uphill in a gulch and a fire running faster forever and ever.

Maclean claimed in interviews to be essentially agnostic. But prayer and biblical language still formed for him a coherent vision of the world and supplied the images he would use to great effect in all his work. Watching his brother Paul fish in “A River Runs Through It,” he sees him in terms that are potent in their ambiguity:

Below him was the multitudinous river, and, where the rock had parted it around him, big-grained vapor rose. The mini-molecules of water left in the wake of his line made momentary loops of gossamer, disappearing so rapidly in the rising big-grained vapor that they had to be retained in memory to be visualized as loops. The spray emanating from him was finer-grained still and enclosed him in a halo of himself. The halo of himself was always there and always disappearing, as if he were candlelight flickering about three inches from himself. The images of himself and his line kept disappearing into the rising vapors of the river, which continually circled to the tops of the cliffs where, after becoming a wreath in the wind, they became rays of the sun.

That halo, always there and always disappearing, becomes the perfect metaphor for Paul: a man of great artistry and beauty with a fly rod in his hand, always in possession of that artistry but not always in a position to use it, and doomed to a tragedy that occurred in a moment outside his sphere of artistry. Eventually he will disappear altogether into the mystery of himself. One other potent symbol in his story–again redolent of the story of Christ–is the right hand with which he casts his fly. We see it again and again in the course of the novella, bigger and more powerful than his left, until it becomes a foregone conclusion that it will have a role in his end. The only solace Norman and his father can take from his death is that nearly all the fingers of that hand were broken when his body was found dumped in an alley, a sign that he had died fighting, a fact Norman must repeat more than once. The hand, in conversation between Norman and his father, becomes a thing they continually inspect, just as Thomas had to inspect the hand of Jesus to prove to himself that Jesus had returned from the dead.

Having begun to write so late in life, Maclean confined his energies to what his idol Wordsworth called “spots of time”–those moments when his life soared above the humdrum and took on the shape and beauty of a story. This gave him the head start he needed, aware as he was that his time for creation was short. Again and again in his work, he makes allusions to such moments: “Poets talk about ‘spots of time,’ but it is really fishermen who experience eternity compressed into a moment,” he writes in “A River Runs Through It.” In the later novella “USFS 1919: The Ranger, the Cook, and a Hole in the Sky,” his reminiscence of his work as a fire lookout in the early Forest Service, he put it this way: “Life every now and then becomes literature–not for long, of course, but long enough to be what we best remember, and often enough so that what we eventually come to mean by life are those moments when life, instead of going sideways, backwards, forward, or nowhere at all, lines out straight, tense and inevitable, with a complication, climax, and, given some luck, a purgation, as if life had been made and not happened.” Finally, in Young Men and Fire, he offers what is by now a more crystallized statement of the same view: “Far back in the impulses to find this story is a storyteller’s belief that at times life takes on the shape of art and that the remembered remnants of these moments are largely what we come to mean by life.”

As The Norman Maclean Reader illuminates, Maclean was attracted not only to spots of time but to tragedies of overconfidence. The first section of the book contains five chapters of a study he began in the 1950s on the battle at Little Bighorn, a book he never finished, although his fascination with what happened to Custer on that hill never left him. That fascination revolved, as he put it, around “how hidden we keep certain aspects of defeat from ourselves,” not aware until too late that our defeat is imminent. He mentions the battle more than once in both “A River Runs Through It” and Young Men and Fire; in the second instance he sees a kinship between the crosses marking the spots where thirteen young smoke jumpers met their death and the memorials to the dead at Little Bighorn:

In the dry grass on both hills are white scattered markers where the bodies were found, a special cluster of them just short of the top, where red terror closed in from behind and above and from the sides. The bodies were of those who were young and thought to be invincible by others and themselves. They were the fastest the nation had in getting to where there was danger, they got there by moving in the magic realm between heaven and earth, and when they got there they almost made a game of it. None were surer they couldn’t lose than the Seventh Cavalry and the Smokejumpers.

It seems now, as editor O. Alan Weltzien points out in his introduction to the Reader, that the story of Custer’s defeat was too impersonal for Maclean to wring from it everything he wanted in a story. In one of the chapters of the aborted book, in fact, Maclean comes close to defining the philosophy of storytelling that would guide his efforts much later: “No literary sense is deeper than the one that recognizes the emotions most inherent in an actual situation and then does everything in its power to preserve this emotional unity and to magnify its impact by addition, subtraction, and embroidery.” Addition, subtraction and embroidery: these were the recipe for the compressed and poetical stories he achieved in A River Runs Through It. His major problem in the writing of the Custer story was that it was too removed in history, too layered in mythology, for him to excavate the emotions inherent in the battle; he simply stalled out in frustration. Only when he turned, two decades later, to events from his own life did he find himself able to write by his creed.

“If an author writes out of a full heart and rhythms don’t come with it,” Maclean once said, “then something is missing inside the author. Perhaps a full heart.” He often said his father had wanted him to be tough, his mother had wanted him to be a flower girl, and so he ended up a tough flower girl. His message is certainly tough–“there’s a lot of tragedy in the universe that has missing parts and comes to no conclusion, including probably the tragedy that awaits you and me”–but it comes garlanded in a prose style very near to unsurpassed in the rhythms of its rolling anapests, its bright flashes of remembrance, its whispers out of time.