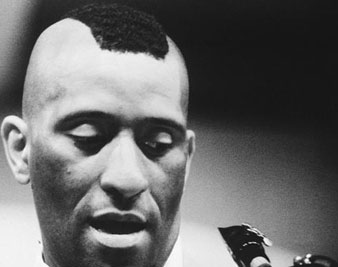

AP IMAGESSonny Rollins in August 1972

AP IMAGESSonny Rollins in August 1972

Carl Smith isn’t technically a bootlegger, but until a few years ago he had a hard time convincing Lucille Rollins and her husband, Sonny, the famed titan of tenor saxophone, of that fact. Smith’s activities throughout much of his adult life–he’s 70–contributed greatly to the Rollinses’ perception of him; Smith’s home in Portland, Maine, contains an extensive library of Sonny’s live performances dating back to the late 1940s, before the budding musician had left his teens or the family home in Harlem. The recordings were made in venues all over the world–some surreptitiously, others by Smith.

Fortunately for the Rollinses–Lucille, who died in 2004, was her husband’s manager and producer–as well as those members of Sonny’s audience interested in purchasing music the conventional way, no matter what the format, Smith is more a munificent fanatic than an outlaw. He is one of thousands of individuals who were sharing contraband music long before digital technology made that possible with a simple mouse click. But unlike the Gen X-ers, Y-ers and Z-ers who banded together as much out of resentment with the fat cats of the Recording Industry Association of America as for cost-free musical pleasure and convenience, Smith never aimed to bring the music biz to its knees. Commerce is strictly prohibited among his fellow collectors, so Smith’s principled difference from traditional bootleggers and other would-be profiteers has always been plain. “Lucille and I were leery of Carl at first…but after some research I found out he’s part of this closed network of collectors who only trade performances,” Rollins told me not long ago. “If you sell anything, no one will trade with you.”

One of Smith’s prize recordings, a 1986 Rollins concert in Tokyo, leads off Road Shows, Vol. 1, Rollins’s most recent album, released this past fall. The music is imbued with all the qualities that have earned Rollins the nickname Saxophone Colossus: the tone as weighty as marble yet as rhythmically fleet and fluid as mercury, the double- and triple-timed phrases that fill the toolkit of Rollins’s fine art of melodic deconstruction. Two other gems, from Umea, Sweden, and Warsaw, Poland (both from 1980), also grace the seven-track disc, and while they’re not the first Smith recordings to make their way into the commercial marketplace–that distinction falls to 2005’s Grammy Award-winning Without A Song: The 9/11 Concert, the disc that ended Rollins’s thirty-three-year association with Milestone Records–they do take the saxophonist, a self-described Luddite, further into the Wild West of digital possibility (peruse the offerings). All of this came about because Smith, with the blessing of fellow traders, made his personal archive available to Rollins’s Doxy Records, a self-run imprint launched in 2005. “Everyone knows that it’s a musician’s dream to own their work,” Rollins told me at the time. “This seems to be the right vehicle for mine, without trying to be a mogul or anything.”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

Perhaps instead of mogul, though, the term “curator”–a shrewd tender of his own art, legacy and image–would better suit Rollins these days. After all, he also tapped into his magnificent collection of private recordings as well as the Carl Smith archive to assemble Road Shows, and now oversees his career in a manner unprecedented for a musician of his generation and stature. Early on, Rollins’s triumphs tended to go hand-in-hand with his sabbaticals from the jazz scene. He often marked each return or phase–the most legendary one followed the two-year hiatus at the turn of the ’60s, in which he could only be heard in public practicing on New York City’s Williamsburg Bridge–with a sartorial shift as strikingly contemporary as his leaps in sonic acuity. The mohawk haircut Rollins sports on the back cover of Sonny Meets Hawk! (1963) is as wondrously eccentric as the sculpted white beard and goggle-like shades he prefers today (the specs were Sonny’s look before they were Bono’s). During a talking-head interview in Robert Mugge’s 1986 documentary, Saxophone Colossus (issued in January on DVD), Gary Giddins, jazz’s foremost critic, gleefully muses on how, in concert, Rollins’s visual sense has the effect of maximizing your pleasure when his playing is at its absolute best–not the kind of talk one generally expects from a jazz aficionado.

And yet Sonny the Curator has always had a nemesis in Sonny the Enigma, an immensely self-critical artist who has struck out onstage nearly as many times as he’s hit the home runs captured on Road Shows. Giddins opines that in striving for thematic solos of “Aristotelian perfection…there’s no hiding for him. You always know when he’s playing very well or when he’s not.” Over the years, some have blamed the lapses on Rollins’s infatuation with funky calypsos, while others cite his use of an electric bassist or the relative youth of his bands. The two concerts in the Mugge documentary make these carps seem especially off base, but the director reveals that his film might not have been made if Lucille wasn’t interested in countering the perception–fostered by the response to many of Rollins’s records of the time–that the saxophonist’s best days were long behind him. “My understanding was that, previously, Sonny and Lucille had been sort of resistant to things like film projects,” Mugge says in a DVD interview. “Fortunately, at that point Lucille was concerned about [what some of the critics were writing] so she agreed to help with the film and convinced Sonny to cooperate as well.”

It’s not hard to see the film’s marvelous opening quintet sequence as a spirited rebuke to the detractors, with Rollins making the most of a panoramic, open-air venue in upstate New York by voraciously digging into “G-Man,” an original composition, for fifteen suspense-ridden minutes. The band is already hurtling along at top speed when Sonny holds a note at the six-minute mark that signals he’s upshifting again; Mugge’s editing catches each band member’s knowing yet awestruck smile as Rollins leads them up Olympus. On a later piece, Rollins’s sense of theater is on display as he leaps from the stage mid-solo and continues playing, even though, as is disclosed later, he sustained a broken heel. Although the film slows down a bit later while on the road with Rollins in Tokyo–he premieres a piece as the featured soloist with a symphony orchestra–it’s still valuable as an example of a world-class artist intent on facing down new challenges. He may have little to prove anymore, but that doesn’t seem to have stopped the Colossus from growing.