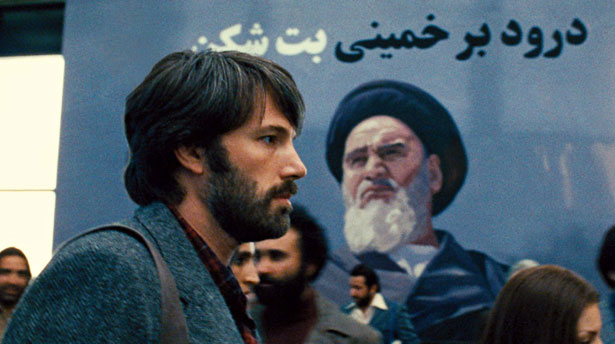

Ben Affleck plays a CIA operative charged with extracting embassy staff from Iran. (Courtesy of Warner Bros.)

This story originally appeared at Truthdig. Robert Scheer is the author of The Great American Stickup: How Reagan Republicans and Clinton Democrats Enriched Wall Street While Mugging Main Street (Nation Books).

What was Michelle Obama thinking? If the card for “Zero Dark Thirty” had been lurking in that best picture envelope Sunday, the gushing first lady would have appeared to the 1 billion people watching to have endorsed the very torture policies that her husband has denounced, at least rhetorically, if not always in practice. Saved from that fate by the Academy’s selection of “Argo,” she tacitly condoned the CIA’s subterfuge in pretending that its covert rescue operation was a genuine film project.

Not an insignificant matter, given the agency’s lengthy history of subverting cultural, journalistic and human rights organizations for its not always admirable purposes. It is not much of a stretch to extend that example to journalists as presumed foreign agents, and that is the charge most often used to kill them. Or human rights workers, religious missionaries, medical personnel or any of the thousands of nongovernment workers who are daily threatened as they go about their work in dangerous lands, advancing their do-gooder notions.

This is the movie season to consider the CIA as a benign force, occasionally stumbling but in the end, driven by good intentions. The example of Iran, where the “Argo” caper is set, is instructive of the absurdity of that view. Iran for the past half century has been ravaged precisely by such CIA antics. To its credit, “Argo” acknowledges, in its opening minutes, that the U.S. government overthrew the last secular democratic leader of Iran and brought the despotic shah to power, and in his aftermath, the religious madness of the ayatollahs. But it is a point soon forgotten, as the film goes on to reveal an Iran populated by inhabitants so universally deranged that their dialogues in Farsi are not even worthy of subtitle translation.

Such translation of Iranian grievances would undermine the outraged innocence of American diplomats that provides “Argo” with its feel-good intent. The fact that our diplomatic corps, heavily staffed by hardened intelligence operatives, had long been a center of power in Iran was glossed over after the opening scene’s mention of the overthrow of democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh. It was an overthrow necessitated by the fact that Mossadegh nationalized the all-powerful British owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, which operates today as British Petroleum.

After the overthrow of the shah in 1979, I interviewed for the Los Angeles Times CIA operative Kermit Roosevelt, who led the coup against Mossadegh. For a quarter century, the United States had denied any connection with the coup, but Roosevelt, a grandson of President Theodore Roosevelt, was about to release a tell-all book on the subject that the CIA had approved, and he was willing to talk.

His caper was much riskier than that detailed in “Argo,” and more central to the one thing that ever mattered to foreigners in Iran—oil. He told me that the CIA had begun the plan to overthrow Mossadegh after a “suggestion” by oil company executives. “The Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. came to us with British authorization,” he explained. “They stopped me in London and put it to me there. I said, ‘Look guys, I can’t talk about this kind of thing now; I’ve got no authorization.’ ”

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

But Roosevelt then took the British suggestion to his boss, CIA Deputy Director Allen Dulles, in December 1952 after Dwight Eisenhower won election, but while lame duck Harry Truman was still in power. Roosevelt told me that he and Dulles kept their plan secret from Truman and his secretary of state, Dean Acheson, because they were sympathetic to Mossadegh as a genuine nationalist leader.

“Acheson was absolutely fascinated by Dr. Mossadegh. He was in fact sympathetic to him,” Roosevelt said in our interview. Instead, he waited until Allen Dulles’ brother, Foster, took over as secretary of state in the incoming Republican administration, and then Dr. Mossadegh would come to be defined by the U.S. as a potential puppet of the Soviets.

In our interview, 25 years after the coup, Roosevelt was at pains to say that in retrospect, the communist label didn’t really fit. “Mossadegh was not pro-communist. … I think that the British were very stupid in negotiations with Mossadegh. … They did not make any kind of effective gesture that he could accept, and I think that was foolish,” he recalled. “I think it was possible to make an offer he would have accepted and that would have avoided this whole blowup. If they had said, ‘OK, we’ll increase the rate (paid to Iran for their oil) we’ll give you a certain percentage of the ownership,’ this would have been the smart thing for them to do.”

Roosevelt left the CIA after refusing assignments to engineer the overthrow of the governments of Guatemala and Egypt. Some four years after toppling Mossadegh, he went to work as a vice president for Gulf Oil where, as he told me, “I was in charge of their … relations with the U.S. government and with foreign governments.” Gulf was one of the U.S. companies favored with oil exploitation contracts by the shah, in power due to Roosevelt.

In 1968, Roosevelt registered in Washington as a foreign agent for Iran. Like many still within the CIA, he was caught by surprise when the shah was overthrown a decade later by an outraged populace, noting “I was not really aware of just how bad things were in Iran until well, really early October,” shortly before the events described in “Argo.”

Now there’s a movie, but it’s not about American innocence.

Even though best-picture contender Zero Dark Thirty had everyone talking about politics in the movies, this year's Oscars ceremony wasn't as political as some have been in the past, Rick Perlstein points out.