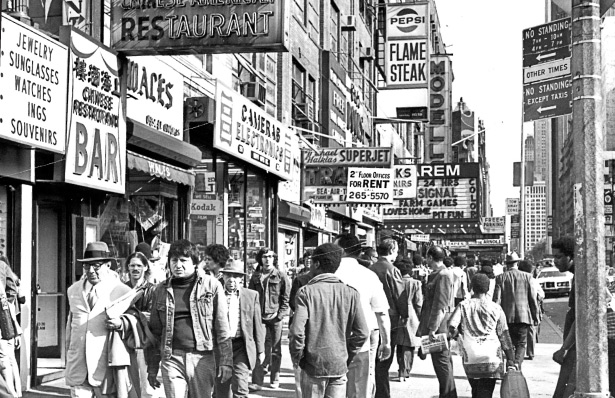

Shoppers hustle down 42nd Street in 1975. (Photo by Peter Keegan/Getty Images)

On a Tuesday in mid-May of 1975, Abraham Beame and Hugh Carey—New York City’s mayor and governor—arrived at the White House to meet with President Gerald Ford. The news they brought was not good: New York City was experiencing a severe cash shortage, and without help, the city would not be able to cover its bills much longer. Beame described a recent demonstration of CUNY students outside of Gracie Mansion; Carey warned that serious retrenchment might mean the collapse of civil peace. The president listened and then said that he needed twenty-four hours to think it over. (“24 hours. Must do what’s right. Bite bullet,” he wrote on a note- pad, probably before the meeting even happened.) The next day, Ford told Beame and Carey that there was nothing the federal government could prudently do to help. The city would have to solve its problems on its own.

Throughout the rest of the year, New York would flirt with default on its massive loans, scrambling to patch together one plan after another, each intended to save the city from declaring bankruptcy while cutting back on the social and municipal services it provided. Today, the city’s heralded renaissance is often contrasted with the bad old days of the 1970s, a dark, distant past through which the city had to pass to arrive at the rosy present. But in fact, the fiscal crisis of the ’70s—and the subsequent budget cutbacks that followed—reshaped the city in ways that continue to influence it even now.

Like most fiscal crises, New York’s was at once long anticipated and a complete shock. Many observers in the early ’70s had noticed that New York was entering a period of difficulty and falling tax receipts, as the city’s economy was rocked by the decline of manufacturing and the flight of the white middle class to the suburbs. New York did provide more services than most other American cities—more about these in a moment—although contrary to the railing of conservatives at the time, its public workers were not paid wages out of line with those of workers in other cities. During the Great Society years, the expenses of the city climbed, particularly those for Medicaid (for which it bore almost 25 percent of the cost, in accordance with state law) and welfare. At first, increases in federal and state aid helped fuel this expansion. But when the economy turned south in the early 1970s, New York turned to borrowing to make up the budget gaps. The tacit assumption of city leaders—rarely spelled out clearly—was that the borrowing was merely a temporary measure. Perhaps national healthcare would pass and the city would no longer have to foot a massive Medicaid bill. Once the economy recovered, the city would regain its fiscal footing.

But by 1975, as recession enveloped the American economy, the banks that marketed New York’s debt (and owned a great deal of it) became increasingly wary about the city, as did investors around the country. Some business leaders began to tell Mayor Beame that if he didn’t cut spending and balance the budget, “managers” should be put in place and made accountable for New York. In extreme times, wrote Jac Friedgut, a vice president at First National City Bank, “many things can be done even if they are technically not possible.” By the spring, the banks told the city that the bond market had closed.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

As soon as its credit was cut off, it became apparent that New York did not have the money to pay its debts—or even to continue to cover payrolls without access to more borrowed funds. The state created the Municipal Assistance Corporation, which was empowered to issue special bonds backed by the sales tax to help the city pay its bills. When MAC proved no more able than the city to market its debt, the state created the Emergency Financial Control Board to oversee the city’s finances and make sure it was moving toward a balanced budget. Finally, with Washington’s help (it agreed in the end to provide the city with some loans), New York made an arrangement with the banks and its unions that kept it out of bankruptcy. The cost was serious budget cuts: over the next three years, the number of police officers and teachers each dropped by about 6,000 and the number of firefighters by about 2,500, transit fares were raised, and tuition was imposed for the first time at the City University of New York.

* * *

Social Democracy Lost

Today, the rituals of fiscal crisis—the blaming of public sector workers, the vilification of the poor who use government services suddenly deemed excessive luxuries—may seem familiar. One American city after another has been rocked by such difficulties in the years since 2008. In mid-March, Michigan Governor Rick Snyder announced the takeover of Detroit’s finances by a state-appointed manager. In the last few years, the cities of Stockton and San Bernardino in California have declared bankruptcy, as have Central Falls, Rhode Island, and Jefferson County, Alabama. To try to keep firehouses open, cities like Baltimore are contemplating selling ad space on fire trucks and rescue vehicles. The local fiscal crises are accompanied by the stoking of anxiety about the fiscal soundness of the federal government and by the debt crises wracking Europe.

Today’s local fiscal crises afflict primarily cities (especially smaller ones) that have been struggling for years. The takeover of Detroit is hardly a surprise—everyone knows the city is broken. New York in the ’70s, on the other hand, was the biggest city in the country, the home of Wall Street, the epicenter of capitalism. The idea that such an apparently powerful urban center could be in fiscal difficulty came as a shock, even to those in charge of governing the city. For people in New York as well as in Washington, DC, the city's problems soon became linked to broader questions about the direction of the country as a whole.

Although there were many local causes of the fiscal crisis—the specific economic problems of New York, the high proportion of the Medicaid and welfare costs borne by the city, and a general willingness within the city government to employ deficit financing strategies—it quickly became seen as a metaphor for the larger breakdown of liberalism in the ’70s. Throughout the postwar years, as historian Joshua Freeman has argued, New York City embodied a particular style of social-democratic politics: one that embraced a strong welfare state, a culture of labor power and solidarity, and a belief in the necessity of using the government (even city government) to help the disadvantaged. It can be hard today to imagine what it was like to live in a city that provided such a rich range of social services, ones that made possible a uniquely democratic urban culture. The city had nineteen public hospitals in 1975, extensive mass transit and public housing, public daycare and decent schools. The municipal university system—the only one of its kind in the country—provided higher education to all, free of charge. Rent stabilization made it possible for a middle class to inhabit the city. For many, the fiscal crisis showed that it was no longer possible for New York to finance these kinds of services. As Christopher Lasch wrote in his 1979 book The Culture of Narcissism, “Those who recently dreamed of world power now despair of governing the city of New York.”

For the rising conservative movement, the fiscal crisis dramatized all of liberalism’s problems: its inability to subordinate sentiment to financial imperatives, its recklessness, its sinful flouting of the norms of rectitude. The right did not take long to draw parallels between New York and the country as a whole in the wake of the expansion of social programs in the Great Society. As President Ford said in his October 29, 1975, speech at the National Press Club (the one that caused the Daily News to coin the famous headline Ford to City: Drop Dead), “Other cities, other states as well as the federal government are not immune to the insidious disease from which New York is suffering…. If we go on spending more than we have, providing more benefits and services than we can pay for, then a day of reckoning will come to Washington and the whole country just as it has to New York.” Ford’s more conservative advisers had long been fiercely hostile to the city. When it first asked for help from Washington early in the spring of 1975, Donald Rumsfeld (then Ford’s chief of staff) responded that such a request was “outrageous” and that acceding to it would be ”a disaster.” Alan Greenspan, the head of Ford’s Council of Economic Advisers, also argued against aiding the city, writing that “there is no short cut to fiscal responsibility.”

Only a month after Ford’s October speech, after a barrage of criticism from such elite figures as the chairman of Con Edison, the president of the Bank of America and the chancellor of West Germany, the administration reversed its position and agreed to extend loans to New York on the condition that the city continue to move toward a balanced budget. Nonetheless, the fact that Ford had been willing to let New York go broke signaled that ideological purity trumped all other concerns for the rising right. Teaching a lesson about the dangers of the welfare state seemed more important than international prestige, Cold War concerns or even the possible economic impact of the city’s default (Ford’s treasury secretary, William Simon, a former municipal bond trader and future president of the Olin Foundation, insisted that New York’s bankruptcy would likely not have a significant effect even on the municipal bond market).

But the political impact of the fiscal crisis was felt far beyond conservative circles. The crisis brought about a transformation of the very language and conception of politics, as the rhetoric of fiscal necessity and business acumen replaced a vision of politics as a domain of struggle and negotiation. Old-time Democratic politicians like Beame had understood urban politics as a world of relationships, negotiations and deals. People with power made arrangements with other powerful people. The investment bankers Beame blamed for “boycotting” the city saw the world differently: they described themselves as mere conduits for the wisdom of the marketplace. Politics mattered less than the vast collective wisdom of the bond market, which rendered New York City and the banks powerless.

The crisis brought about a change in the city’s leadership, as clubhouse Democrats were deposed in favor of a younger generation of business-friendly liberals. For these new leaders, the downsizing of New York became a badge of honor: a sign that liberals were not beholden to such special interests as organized labor but could speak the rhetoric of efficiency. The old faith in the political importance of the working class, the New Deal sense of the necessity of government action, gave way in the fiscal crisis to a liberalism that borrowed its framework and its values from the private sector.

* * *

A Bitter Fight

In New York politics, one can occasionally hear people express nostalgia for those days as a time when business, labor and government got together to do what needed to be done to save the city through the harsh fiscal remedy of budget cuts. Although it was true that union presidents and business leaders alike ultimately acquiesced to the program of retrenchment, the image of unity is largely a product of hindsight. New Yorkers in the ’70s fought bitterly about the crisis. The city was divided by protests against budget cuts. Many New Yorkers blamed the banks for refusing to lend the city money. Although most of the city’s unions finally went along with the cuts, they started out by organizing large-scale demonstrations criticizing the banks; at one point in the fall of 1975, they briefly hinted at a general strike. People occupied firehouses to keep them open, organized massive campaigns to save college campuses (such as Hostos Community College in the Bronx, which was threatened with closure) and threw their trash into the middle of the street to protest the mass layoffs of sanitation workers and resulting slowdown in garbage collections. Public sector workers who had been laid off blocked traffic on the Brooklyn Bridge and highway workers picketed at the Henry Hudson Parkway; at one point, corrections officers angry about layoffs organized a demonstration briefly preventing people from passing over the bridge to Rikers Island. In part, the city workers were enraged at the layoffs that destroyed their economic security—but the intensity of the protests also signaled the sense that the city was at a crossroads, divided between two different visions for its future.

For New Yorkers outside the halls of power, the crisis appeared bewildering: How could a city that seemed so rich suddenly have so little money? But as firehouses closed, mass transit stalled, libraries shut their doors, school class sizes swelled, routine services like garbage collection became unpredictable, and thousands of would-be students found themselves shut out of CUNY because the university simply stopped processing their applications, the crisis helped to spawn a new conservatism in the city as well. Letters poured into the offices of elected officials. Some of them expressed anger at the treatment of the poor: “Why don’t you line us up against the wall and shoot us?” one correspondent asked Governor Hugh Carey. But many others vented rage at the “welfare people” (especially Puerto Rican and “Mexican” immigrants) they believed had brought the city to this pass. The bankruptcy of the state made it difficult for people to assert any claims on it, as economic austerity helped generate a new political disengagement.

Today, the fiscal crisis in New York may seem a distant memory, like the graffiti-covered subway cars of the era or the fires that once blazed through Bushwick, a neighborhood now dotted with artisanal chocolate shops and pizza places that win raves from The New York Times. But the diminished expectations we have for the public sector and the increasing difficulty of living a middle-class life in the city suggest the legacy of the fiscal crisis even now. City governments today—including New York’s—seem primarily to be vehicles to attract and maintain private investment. Business improvement districts and public-private partnerships involve companies directly in paying for the services they receive, while the city sweeps away community challenges to business-oriented development. This is supposed to lead to improved services for all; yet over the same years that have seen the rise of this business culture in city government, New York has become the most unequal city in the country—the gulf between rich and poor widening in ways that would have been hard to imagine even in the early ’70s.

In the artistic and intellectual circles of the left, there’s an undeniable nostalgia for New York in the ’70s—when CBGB opened its doors, working artists had lofts in SoHo, hip-hop was invented, and the Lower East Side became the home to a new musical and artistic scene. It might be easy to dismiss such feelings as the sentimental romanticism of a privileged generation that has grown used to traveling the subways without being anxious about crime—or just the appeal of a time when rent was cheap. But looking around the city today, saturated with money and starkly divided by wealth, the very bleakness of the ’70s seems a refuge, a time of possibility. The violence and brutality of a city in free fall was real. Yet in the literal bankruptcy of the political establishment, there was also a kind of freedom, a political and cultural openness; there was no need to pretend that everything was all right.

The 1970s—in New York and around the country—saw the dawning of a new era of austerity, as the earlier assumptions of economic growth faded. The contraction of the state also meant the shrinking of the social imagination. The stern dictums about the necessary limits of political dreams contrasted sharply with the new populist utopianism of the free market, where anything might be possible. We still live today in a society defined by these two poles: the harsh limits of the political sphere and the delusional boundlessness of the market. Although it wasn’t solely responsible for bringing the city into this new age, New York’s fiscal crisis marks the boundary between the past and the present we still live in today.

Read all of the articles in The Nation's special issue on New York City.