© All rights reserved by MIGRAHACK

Two days of people huddled over a glowing computer screen and chugging cup after cup of coffee to stay awake. Programmers pouring out lines of code and analysts moving their cursors swiftly through spreadsheets with hundreds of lines of data. In many ways, MigraHack is your typical hackathon, an event in which programmers come together to develop open access digital tools. But MigraHack’s goal for this intense weekend is more ambitious—to redefine the country’s immigration debate through data and visual storytelling.

As much of the country waits on Washington for some movement on immigration reform, a burgeoning group of web programmers, data analysts, journalists and immigrant rights advocates is banding together at hackathons to expand reporting around immigration through technology. MigraHack is a partnership between RDataVox, a non-profit network of people who collaborate with US ethnic media, and the Institute for Justice and Journalism, an organization that strengthens reporting on social justice issues. Another similarly-minded network that hosts hackathons is UndocuTech, which is a product of the immigrant youth-led organization United We Dream and the Center for Civic Media at MIT. These two organizations are opening the door for hackathon events and culture to directly serve the country’s immigrant community.

“I think immigrants are now more confident and want to be a part of this country,” says Claudia Núñez, who launched MigraHack in 2012, during her time as a John S. Knight Fellow at Stanford. ‘That same feeling applies to MigraHack. The message is that you’re a part of this country and we want to hear from you.”

Núñez did not hear that message when she immigrated to the US from Mexico fourteen years ago at the age of 23. She knew no English and little about the country she would soon call home. Previously a reporter in Mexico, she started working as an investigative reporter with La Opinión, a Los Angeles-based Spanish language newspaper. In 2010, as mainstream outlets began to experiment with data visualization and other web-based storytelling tools, Núñez saw a serious gap in data analysis on immigration issues that she thought could be filled by ethnic media reporters who understand immigrant communities and are often immigrants themselves. Núñez began training herself on web development and design through YouTube videos and online tutorials, and as a part of her self-training, she started attending hackathons, which she found were typically dominated by white men.

“I was like ‘Where are the people like me?’” Núñez says. “I still had difficulty speaking English. I was still working out my immigration status.” Steadfast in her commitment to help ethnic media utilize these new storytelling tools, Núñez decided to host her own hackathon in Los Angeles that would bring together programmers, immigration journalists and activists to develop projects on immigration.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

La Opinión donated office space. A local bakery donated pastries. A good friend who is a chef offered to cook. Núñez knew a group of journalists who were interested in participating, so she attended a meet-up in Pasadena hoping to meet programmers who might join. In a crowded room of people, she marched up to the microphone and said, “I’m Claudia Núñez. I’m a reporter serving the Hispanic community and I need your help.” The response was overwhelming. In the end, dozens of programmers, who worked everywhere from Google to NASA, signed up to participate in MigraHack’s first hackathon.

Los Angeles MigraHack, which took place in December of 2012, was intended for thirty participants. One hundred people ended up participating, with at least another twenty-five on the waiting list. The hackathon produced a number of projects including a map illustrating how long immigrants from certain countries waited to receive US green card sponsorship and a tongue-in-cheek Dummies guide to crossing the border illegally that includes data on apprehension. The success of the first hackathon inspired Núñez to host a second one in Chicago in May, which included 120 participants with another twenty-three on the waiting list. The participants ranged from programmers to non-profit advocates to tech geeks.

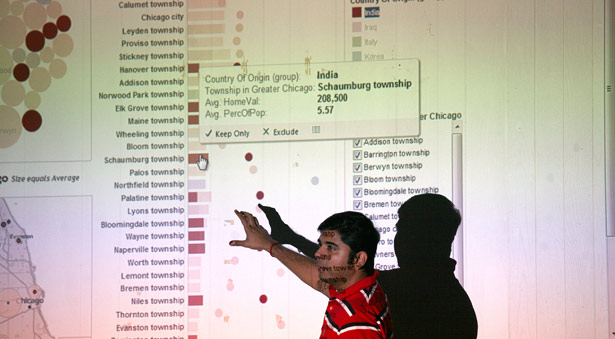

Participants at the Chicago MigraHack were trained on Google Fusion Tables, a data visualization tool, and data mining, a data analysis process that looks for patterns using spreadsheets and a free data visualization software called Tableau Public. After the workshops, participants worked in teams using different data sets that the organization got from the Census, universities and research organizations. Each team included programmers, journalists and advocates, which Núñez says creates a stronger team and project. At the end of the hackathon, a panel of judges, which included investigative journalists, data experts and programmers, evaluated the projects. Five teams were selected as winners, splitting $7,000.

“We don’t get enough opportunities as tech people to interact with people from other disciplines and with other skills, much less work really intensely on a project together,” says David Eads, a news applications developer for the Chicago Tribune and co-founder of FreeGeek Chicago who worked as a mentor at the Chicago MigraHack in May. “There is a spirit of really trying to say something meaningful with the data rather than make something neat or nifty.”

Eads worked with two journalists from the Chicago Reporter, along with a web developer and a freelance photojournalist on one of Chicago MigraHack’s winning projects: Finding Care. Finding Care is a website that covers issues facing undocumented immigrants who are left out of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. The project puts a human face on these issues by focusing on the story of Jorge Mariscal, an undocumented 24-year-old man in Chicago who needed a kidney transplant but was ineligible for the organ transplant list because of his immigration status and lack of insurance. In Mariscal’s case, members of his church went on a hunger strike, eventually pressuring Loyola University Medical Center to admit him. His mother donated a kidney. But, as Finding Care points out: "Many undocumented immigrants are not as lucky. Most don’t have health insurance. They often have to pay out of pocket for care or go untreated."

“We’re not just working alone on our couch,” says Antonio García, a front-end web developer and contract consultant under his own business Coshimel. “The environment at a hackathon is entirely different. There are a lot of ideas bouncing around. It’s a great place to come up with a solution.”

García worked with a data analyst, an immigrant rights advocate and a journalist on an interactive map of Secure Communities, a Department of Homeland Security program designed to alert Immigration and Customs Enforcement of undocumented immigrants who are booked into jail. The program is intended to target people who commit a crime, but has ensnared countless undocumented immigrants with no criminal charges. Rather than sifting through pages of numbers, the interactive map easily shows where the program is more aggressive. On the map, dark blue counties denote high numbers of immigrants swept up by Secure Communities and lighter hues show counties with lower numbers.

For García, the project was personal. An undocumented immigrant himself, he is now able to work and live without fear of deportation under Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a program started in 2012 that protects certain undocumented immigrants who came to the US as children from being deported. But until last year, García lived with the constant threat of being suddenly removed from his home country.

“I grew up in a suburb and often times felt afraid even to go get milk,” he says. “From a social justice standpoint [Secure Communities] drives me crazy, but from a programmer standpoint, it really bothers me to see a system in use that does not work. It’s an issue that attacks me from all sides.”

As MigraHack utilizes hackathons to bridge technology and journalism, UndocuTech sees hackathons as an opportunity to bridge technology and activism. The network was formed through a partnership between United We Dream, a national organization of undocumented immigrant youth, and MIT’s Center for Civic Media in order to expand the immigrant rights movement’s technological capabilities.

“We saw how other movements were embracing media and technology into their organizing strategy,” says Rogelio Alejandro Lopez, a research assistant with the Center for Civic Media at MIT who has been an immigrant rights activist since his days at the University of California, Los Angeles. “The conversation began with ‘What would that kind of organizing around technology look in immigrants rights?’”

UndocuTech held its first “UndocuHack” on June 1, as part of the National Day of Civic Hacking, a hackathon event aimed at addressing community issues around the country. UndocuHack had twenty participants across four different locations—Boston, Los Angeles, Seattle and Washington D.C—who were helping to develop a prototype app called Education Not Deportation.

“One of our goals is to raise awareness and bring the human element of this debate to light,” says Lopez. “We acknowledge that the immigrant voice is still largely lacking in mainstream media. There is an empowering element to being a part of the creation process of making your own media and telling your own story.”

On October 5, UndocuTech and MigraHack are teamed up to host a storython under the Twitter hashtag #11milliondreams. The storython was a two-day event at UCLA’s Downtown Labor Center and MIT's Media Lab in which participants created digital stories about their immigration to the United States. Remote participants also produced their own stories online and tweeted them using the hashtag. The groups are trying to build support for United We Dream’s 11 Million Dreams campaign, which demands that Congress create a pathway to citizenship and end senseless deportation for all of the country’s undocumented immigrants.

To learn more about UndocuTech or MigraHack visit their websites at undocutech.org and chicagomigrahack.com.

Read Aura Bogado on why California just got a little safer for undocumented residents.