Hillary Clinton is under fire again for planted questions, but this time she did nothing wrong.

Clinton pulled a Perot this week, buying a full hour of national television to directly address voters before Super Tuesday. Her campaign convened a virtual town hall, "Voices Across America," and broadcast it on the Hallmark channel and HillaryClinton.com. On the scale of managed presidential campaign events, it was moderately participatory: more than a one-way stump speech, less than an open coffee klatch in Iowa. Specifically, the campaign screened submitted questions, and then Clinton spoke with selected voters, who were sometimes flanked by endorsers or supportive crowds.

Yet the event was the "opposite of interactive," blogs Zephyr Teachout, former Internet director for the Dean Campaign:

By spreading a video message instead of handling press questions, she used the internet to actually reduce interactivity, instead of increase it–she didn’t have to interact with [live] questions…

Teachout is a sharp, passionate analyst of web politics — I’d recommend her new book about the Dean Campaign to anyone who wants to understand what really went down in 2004. But I think it’s a mistake to knock a political event simply because it is not 100% interactive. Sure, one potential benefit of Internet politics is deeper interaction between citizens and their leaders. But another is using the web to route around the filters and elites that separate the candidate from the public. Clinton’s town halls and web chats enable voters to hear directly from her, just like Obama’s one-way YouTube address. And as I’ve documented before, the public shows a remarkably high interest in hearing directly from these candidates. We can learn a lot about candidates’ plans, policies and character by listening to them, even if it’s not in a conversation.

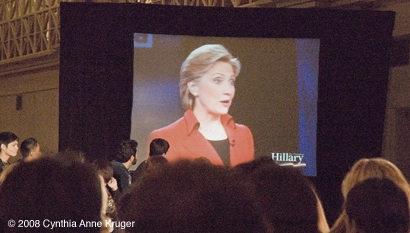

Voters in San Francisco watch Clinton’s virtual town hall. Photo: Cynthia Anne Kruger

Voters in San Francisco watch Clinton’s virtual town hall. Photo: Cynthia Anne Kruger

Another key dimension is disclosure, which Teachout also raises. The questions appeared pre-selected, but neither the Hallmark program nor Clinton’s website provided much information on that front. The Times’ Brian Stelter explains:

Mrs. Clinton participated in what amounted to a one-woman debate. A casual viewer could have mistaken the paid programming, purchased last week by her campaign, for a news broadcast, save for a disclaimer at the beginning ("I’m Hillary Clinton, and I approved this message") and a logo in the corner of the screen that rotated between the words "Hillary" and "Vote Feb. 5."

That approval disclaimer is required by federal law for TV ads. But the FEC has not caught up to virtual campaigning. The rules should require on-screen disclaimers for the entire broadcast, so that all viewers know what they’re watching. A banner reading "paid political program" would do the trick.

We can’t wait around for campaigns to explain their managed events, either. The FEC should require campaigns to prominently explain the format of these virtual events on their websites. There is nothing wrong with culling questions in advance. (Academic and political panels do it all the time, on the theory that you can only take so many questions about a 9/11 conspiracy.) But obviously, the public has a right to know whether questions are live or pre-selected.