“Alright, you 90,000 redeemers, rebels and radicals out there.” So opened the inaugural call for Occupy Wall Street. Linked in a tweet that Adbusters, the Vancouver-based activist collective behind the eponymous anticonsumerist magazine, posted on June 9, 2011, their charge went on: “The time has come to deploy this emerging stratagem against the greatest corrupter of our democracy: Wall Street, the financial Gomorrah of America.”

Inspired by the Arab Spring; protests in Egypt’s Tahrir Square; and 15-M, the mostly youth-led anti-austerity movement that erupted in Spanish cities in 2011 (including an outpouring of 28,000 protesters in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol square, in 2011), the idea was for 20,000 people to flood Lower Manhattan and occupy Wall Street for several months.

“Once there,” the text read, “we shall incessantly repeat one simple demand in a plurality of voices.”

In a few short weeks, the forty who came on September 17 turned into 4,000, and what started as a message online turned into a movement. The demands originally aired at New York City’s Zuccotti Park were echoed in demonstrations in London, Lima, Johannesburg, and Jakarta—all over the world.

Ten years ago, when Accra Shepp went looking for such a swarm, he found himself at Zuccotti Park “under a patch of trees, surrounded by enormous skyscrapers on all sides.” Initially, without his camera, he just observed, listened, and felt the pulse of the people. Many of them were camping out there indefinitely; others came briefly, on a lunch break or after work, to declare their solidarity to this cause.

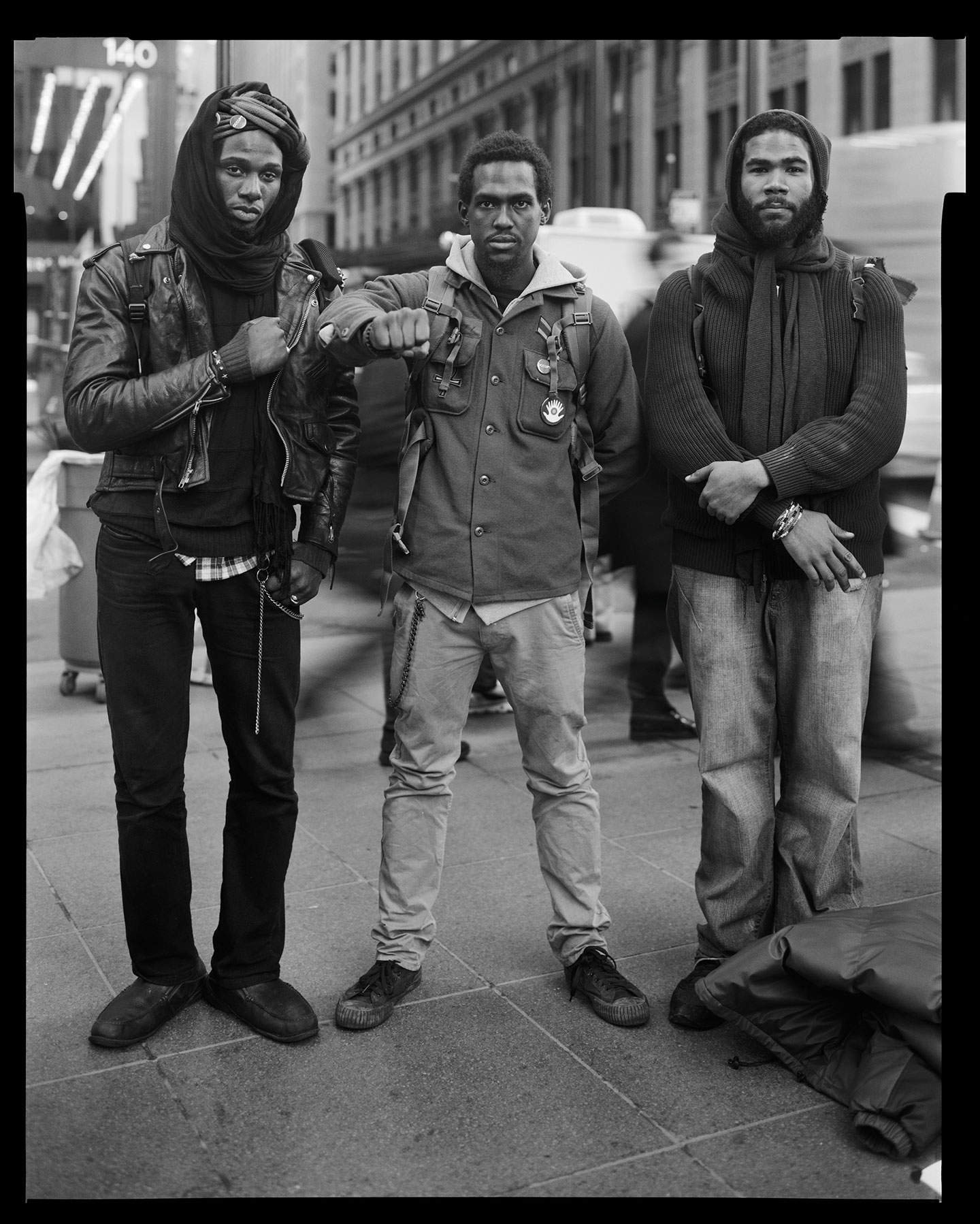

When Shepp next returned, he knew the events unfolding before him were real, and thus worth documenting. A private park was abuzz with experiments in economic justice. So he used a view camera, typically used for large-format images, to make portraits of the protesters and to capture this history.

An interracial couple holds each other and sits on a curb. On the woman’s knee, a sticker reads “Make Out, Not War.”

A woman wearing a black burka and Red Cross armbands, sits in a folding chair with a small sign saying “this space occupied” underneath her left foot.

A middle-aged, white father hoists his bright-eyed daughter, a toddler, on his shoulders. Their eyes sweep the crowd with the skyscrapers looming large around them.

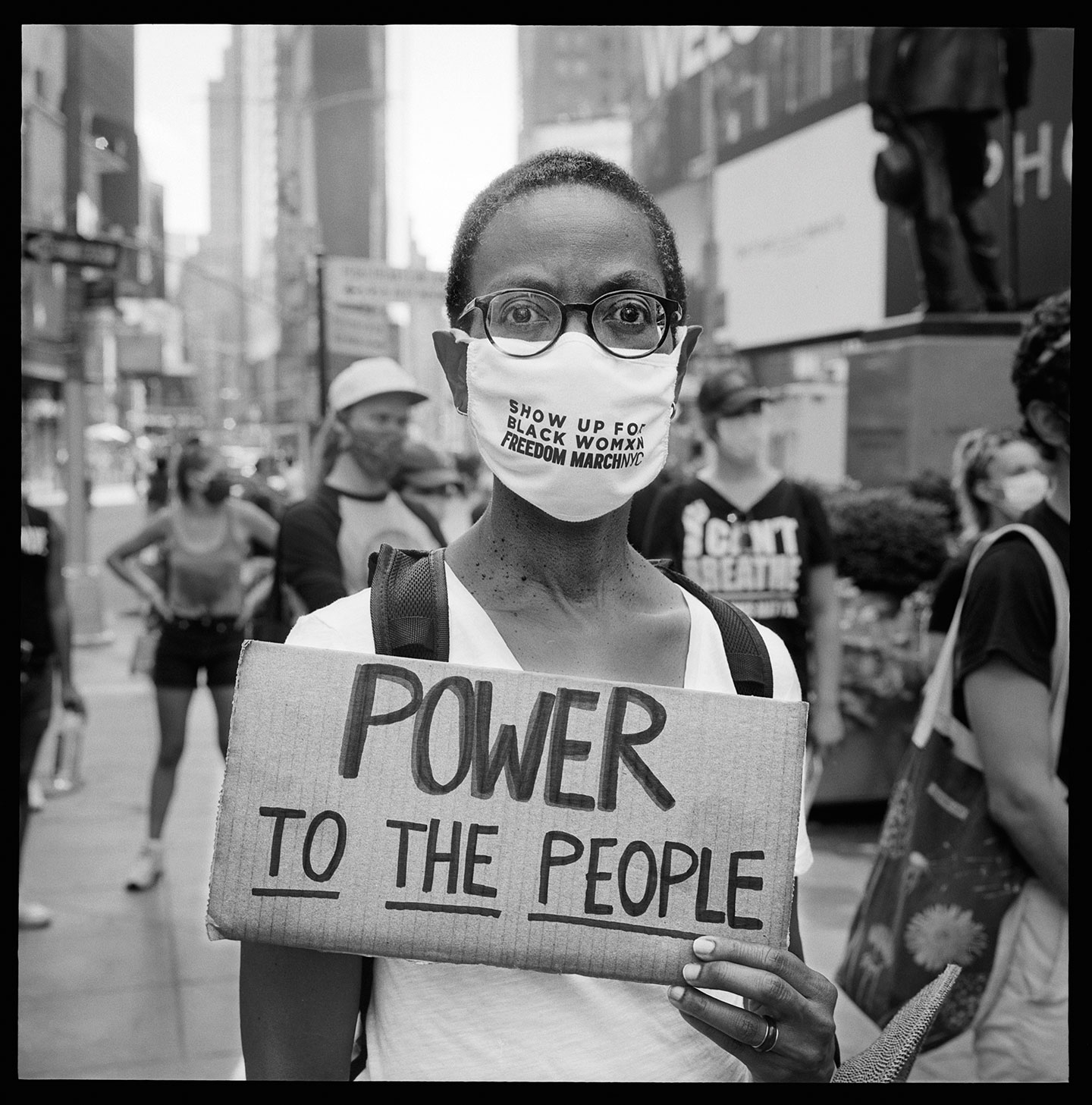

Appearing together in his new book, Radical Justice, these people represent the many citizens that made Occupy possible. In turn, Shepp’s black-and-white photographs dissolve the boundaries between the individual and the collective, reminding us that each person who was present (even the police officers, the newscasters, and anti-Occupiers) was a fundamental player in this revolutionary movement.

Ten years later, as we strive to overcome the ongoing repercussions of the Trump presidency, the Covid-19 pandemic, and the brutal reality of climate change, we continue to confront the severe economic inequality that inspired Occupy Wall Street in the first place.

But we are also living out the power of their early call to action. Our two paramount social justice movements, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, continue to engage the horizontal structure (they have founders, but no one leader) and the political strategy (a blend of social media and old-school organizing) that they, in part, inherited from Occupy a few years earlier.

Similarly, the presidential bids of Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders in 2020, as well as the rise of the progressive left within and outside of the Democratic Party, are impossible to imagine without those two long months of organizing in Zuccotti Park.

There aren’t many artistic renderings of Occupy. Anarchist Marisa Holmes’s 2016 documentary All Day All Week: An Occupy Wall Street Story is a notable exception. As a result, we are often left with little more than anecdotes of how diverse and varied the demographic makeup of the movement was. Radical Justice documents that history and reminds us that activists who have held our country accountable then are not so dissimilar from those who took to the streets in the summer of 2020. In doing so, Shepp’s photographs channel the spirit of Occupy, and its biggest hope as expressed in that original e-mail from Adbusters in 2011: to “[awaken] the imagination and, if achieved, propel us toward the radical democracy of the future.”