About an hour west of the New Mexico–Arizona border, an expanse of highway, sky, and sagebrush-spotted terrain ends in sandstone cliffs. The red-orange walls drop down into Canyon de Chelly, the only national park operated on land still owned by the Navajo Nation. This summer, as the per capita rate of coronavirus cases in the Navajo Nation surpassed New York state’s, Kauy Bahe, 19, found himself standing on the canyon’s edge as he delivered food to a Navajo elder and her family as part of a mutual aid effort.

“It was a beautiful spot,” Bahe (Navajo) said, describing the woman’s cornfield and hogan (a traditional Navajo home made of wood and packed soil) outside Del Muerto, Ariz. But “she was telling us about the struggles for water, about how they don’t have running water there and how they have to drive 30 minutes” to buy it.

Across the United States, activists have responded to the Covid-19 crisis with anarchist strategies, like mutual aid. In Window Rock, Ariz.—the seat of the Navajo Nation—the K’é Infoshop is one such group, and has been supplying elders, families, and the immunocompromised with food and medical supplies. But the Infoshop’s members, like Bahe, say their style of autonomous organizing has distinctly Navajo roots.

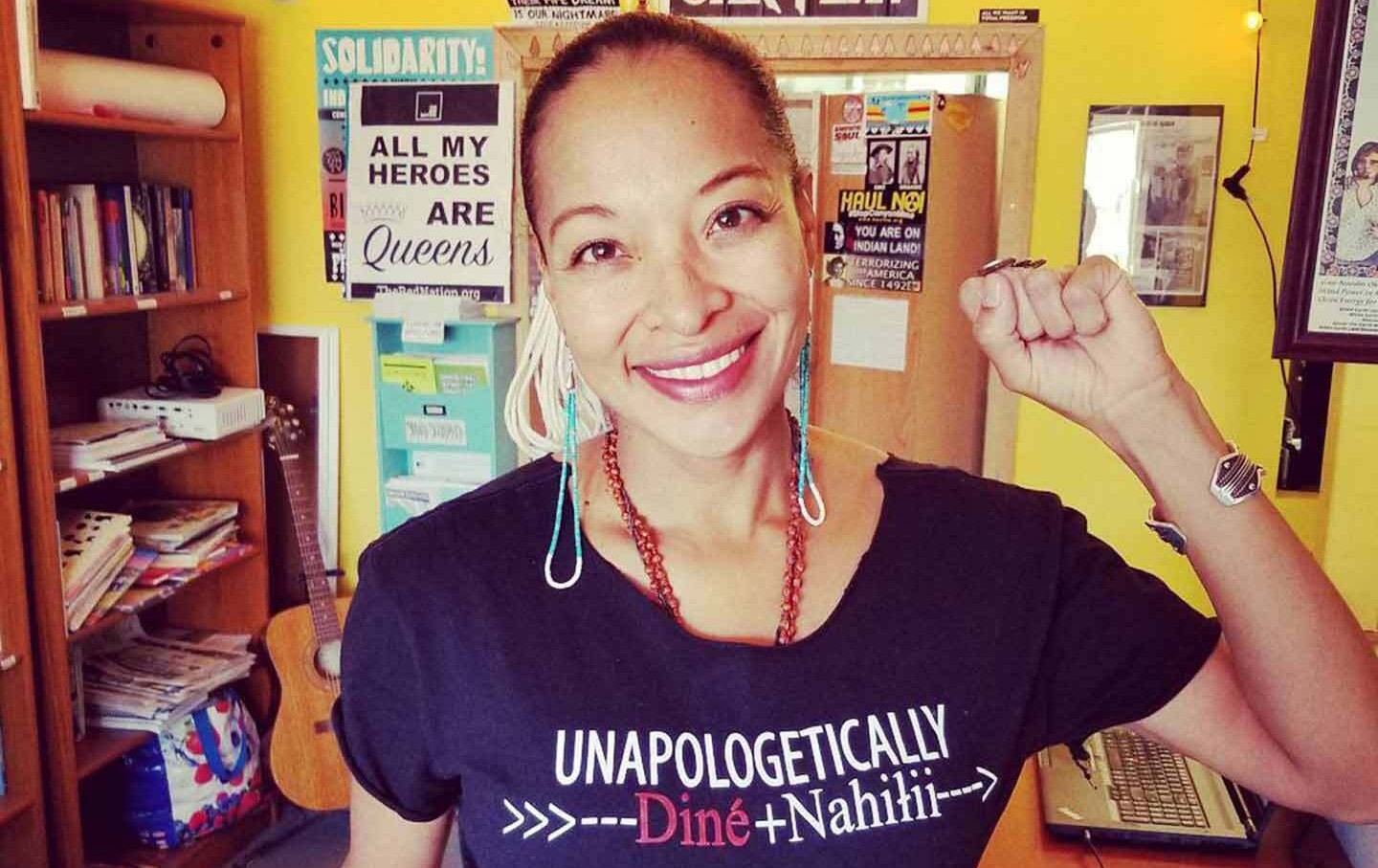

In September 2013, Brandon Benallie (Navajo/Hopi) and Radmilla Cody (Navajo/Black) had just moved to Flagstaff, Ariz., only about 200 miles from the Navajo Nation, when heavy rains flooded towns and destroyed homes across the reservation. Cody, a musician, and Benallie, a cybersecurity expert who’d grown up watching his family organize against resource extraction, quickly planned a benefit concert and collected aid for those affected by the floods. The next year, the Assayii Lake Fire forced dozens of Navajo families to evacuate their homes, and Benallie and Cody organized another concert. Then, just months later, news broke that three teenagers had beaten and murdered two Navajo men in Albuquerque, N.M. The incident reminded Cody and Benallie of the many stories they’d heard growing up of Indian rolling, the assault or murder of homeless Native Americans in white towns along the Navajo reservation.

After that series of events, Benallie and Cody knew that they wanted to fully commit to mutual aid work, and so they formed their own Infoshop, an anarchist community space. They began by setting up a tent outside of the Navajo Nation Museum in Window Rock, but as Indigenous organizing ramped up in 2016 ahead of the Standing Rock demonstrations, they decided they wanted a permanent space.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →Just five minutes from the Navajo Nation government complexes, the K’é Infoshop opened its doors in April 2017 out of a vacant coffee shop. Inside, Benallie, Cody, and other early collective members painted each wall to correspond with the sacred Navajo colors—black, white, turquoise, and yellow—and began stocking the space with books and zines. Near the entrance, they hung a painting of a women’s turquoise-ring-clad hands wrapped around jail bars—a piece by a member who the group says was unjustly arrested in a police raid of the nearby flea market while she shared her lunch with a homeless group. In the back, they filled bookshelves with titles like Corn is Our Blood, Indigenous Men and Masculinities, and Red Power Rising. And then, across the back wall, they put up red stenciled letters that spelled out, “K’é does not discriminate.”

Anthropologists often describe k’é as the Navajo kinship system, but Benallie and Bahe told me it’s much more than that. “It’s our theory of everything,” Benallie said. “It’s our string theory. It’s how we’re connected to everything—but specifically how that kinship is reciprocated and maintained.”

K’é “is this huge overlapping philosophy that the whole universe is interconnected,” Bahe explained. “But it’s also these relationships that we have with one another and with the elements that exist in the world, whether that be the weather or the water or the animals.”

Growing up, Benallie said he learned about organizing from family and community members protesting the Black Mesa coal mines and uranium mining on Navajo land. Benallie said his grandfather always told him, “We are all given unique gifts and abilities, and we must do what we can to provide for others with our unique gifts and abilities.”

He added that at the time, “we didn’t know it as mutual aid, that was just k’é.”

Although there’s a distinctly European language to describing contemporary anarchism, Benallie said he believes that the movement has long been influenced by Indigenous ideas.

“Being Diné could be considered anarchist because we never had chiefs; we didn’t have a hierarchy. It was always horizontal,” Benallie said. “Communism and anarchism derived ideology from Franciscan missionaries who came here in the 1500s and 1600s and studied Indigenous societies. And you have Engels, Marx, and Bakunin reading the journals of these religious figures and how these religious figures describe Indigenous societies at that time.”

Benallie argues that Navajo kinship began to break down as the tribe tried to negotiate with the United States government. “The first version of the Navajo Nation government was called the Navajo business council,” he said. “It was formed primarily to facilitate the signing of oil and gas leases, and coal leases, in the 1920s.”

Once horizontal, Benallie said, Navajo society became patriarchal and hierarchical—and that structure facilitated the destruction of land and water for resource extraction. That history explains why Diné anarchists like Benallie, Cody, and Bahe were leery of tribal and federal pandemic relief efforts—and wanted to organize their own.

As soon as the coronavirus hit the Navajo Nation, K’é’s members had a conversation about how they could help. Benallie said he was initially wary of doing mutual aid work—he was concerned about the health of collective members and their families—but youth members like Bahe spoke up and said they were willing to take the risk. K’é turned to the food pantry it had stocked for weekly solidarity meals with unsheltered community members. “What takes us a year to give away was gone in two weeks,” Benallie said.

At first the Infoshop was alone in its relief efforts in Navajo Nation, but by April and May, other mutual aid projects began to emerge. The youth-led Navajo & Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief project raised funds to place large orders with companies like Shamrock Farms and organized teams to distribute upwards of 10,000 pounds of food each week across the 27,000 square miles of the reservations.

Bahe and other Infoshop members joined the Navajo-Hopi relief team operating out of Fort Defiance, Ariz.—six miles north of Window Rock. Bahe said the group mostly served nearby towns, but on occasion he found himself miles away, at sites like Canyon de Chelly.

As the Navajo government tried to control the spread of the outbreak, it instituted curfews and stay-at-home orders that likely saved lives, but made it more difficult for families to travel to one of the reservation’s 13 grocery stores. Mutual aid groups acquired essential worker passes to distribute food after curfew, but Bahe said organizers still faced pushback from the government.

“We were harassed on multiple occasions by Navajo police pulling us over and telling us that our letters and our badges weren’t valid,” Bahe said. “In one instance the police officer, she sent us home and we had a van full of food.”

Speaking about the impacts of the pandemic and rapid growth of mutual aid groups across the country, Benallie noted, “Every time capitalism fails, we land on socialism, we land on anarchism, to take care of us.”

“I hope it makes people question who is there for them. Was it the $1,200 stimulus check or six months of unemployment? Or was it the good people of the earth who were organizing resources and material needs to make sure that you don’t go to sleep hungry or that your children don’t go to sleep hungry?” he said. “Capitalism fosters this unhealthy, highly individualist view of oneself. People began to forget their responsibilities to each other, to the land, and began to only worry about how much they can benefit from the imbalance from broken kinship.”

As organizers consider strategies to care for their communities in the absence of government support, Benallie urges them to remember their relationships to one another and to the planet. “We can’t do this alone. We need all of the good people of the earth to come together.”