Bengali Youth Speak Out on State Violence Against Student Protesters

Over 200 have reportedly been killed and around 3,000 arrested during the Bangladesh student protests. As the movement continues, we spoke to young people in both the US and Dhaka.

Protesters during a demonstration demanding justice for the victims arrested and killed in the recent violence over quotas in government jobs.

(Fatima Tuj Johora / Getty)

On July 15, students in Bangladesh began protesting the quota system that reserves 30 percent of government jobs for the families of “freedom fighters”—or veterans of the 1971 War of Independence against Pakistan. Student protesters demanded instead the reinstatement of a merit-based system for government jobs, which they fought for in 2018 after similar protests. However, a written petition from members of Bangladesh’s veteran class urged the court to reapply the quota in June, leading to the protests of the last few weeks.

Young Bengalis have come to the streets in massive numbers. But what started as an attempt to represent the marginalized classes of the country through peaceful demonstrations quickly became a bloodbath after authorities began using excessive force. The Bengali government shut off Internet access on July 18 as students quickly shifted the movement to protest state repression and police violence. As of July 25, over 200 people have reportedly been killed and the Bengali police have arrested around 3,000. Currently, over 27,000 Bangladeshi soldiers are deployed across the country to curb the movement.

As the protests in Bangladesh continue, StudentNation spoke to Bengalis both in the United States and in Dhaka. Some students have requested pseudonyms for their safety. Their responses have been edited for length and clarity.

I’ve seen many protests in Bangladesh but I could never fathom this level of violence from the government over a student-led protest.

It has affected students like myself who come from middle- or lower-income households. Not only did the sudden Internet cutoff disrupt telecommunication, but it also meant that the only source of income for a vast majority was stopped.

My family has suffered immensely, and we still haven’t been able to recover from this blow. A good amount of our finances are directed to my mother’s cancer treatments. Naturally, this outage has spelled doom for us with the uncertainty of when things will go back to normal, putting our entire livelihood on the line.

Outside of my house, I watched members of the Awami Student League [a political party composed mostly of descendants of freedom fighters that overwhelmingly supports the current prime minister, Sheikh Hasina] get ready with machetes, hockey sticks, and rods, while the students were only armed with banners and slogans.

My shock was nothing compared to when I saw the news after the Internet returned. It may seem like the Internet is back, but I still cannot access Facebook, Messenger, or Instagram or make phone calls on WhatsApp. Specific apps on the Play Store cannot be downloaded, like free VPNs or other communication apps.

The government is afraid and immature, shooting unarmed students carelessly and letting stray bullets hit random people and children in their own homes. Ironically, as much as they apparently “defend” our country’s martyrs, they’re the ones conducting a new Operation Searchlight on their youth. [Operation Searchlight was carried out in 1971 by the Pakistani military to suppress the Bengali nationalist movement.]

I don’t know when things will go back to normal, or if they ever will, but our students did not deserve to die just because they asked for equal opportunities. I’m living in a country where you’re called a rajakar [“traitor”] and get shot down if you stand up for your rights.

—Azia Tasnim, 20, Dhaka, Bangladesh

As a Bengali in the diaspora, the student quota movement in Bangladesh resonates deeply with me. For many, including friends and family in Bangladesh, this movement represents a critical juncture in the nation’s development. The courage of these students—facing bullets, tear gas, and arrests—reminds us of the power of collective action and the importance of protest.

This movement is a source of both pride and concern. Pride, because it shows the resilience and determination of the Bengali youth to improve their country’s future. However, there is also concern due to the government’s vile response, which includes power outages during protests (even during elections) and the use of excessive force, proving the extremes to which the government will go to suppress disagreement. For a week, it has been almost impossible to contact my family back home. There’s always a worry in me for the people back home, especially when it’s happening where I once grew up.

A close friend of mine told me that his cousin experienced police brutality firsthand alongside his friend who was tragically killed by police gunfire. His last words were, “You let me go and run. I can’t make it.”

For many years, I have witnessed and heard through family and friends back home about the misconduct of Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her government. Their corruption and rigged elections demonstrate that she should step down as a leader. Instead, she dismisses the people of her country as razakars (those who helped Pakistan during the war in 1971) for seeking equality.

—Anim Sams, 16, USA

When I first heard about the brutality against the protesters, I thought, “This reminds me of NYPD tactics against pro-Palestine protesters.” However, the atrocities in Dhaka were far more severe than I or anyone in my family imagined. Students like me are protesting against the Bangladeshi government, and it made me think about how, if my fate had been different, I might also be a student protesting in Dhaka—possibly severely injured or martyred.

Our grandparents fought for independence, not for privilege. The situation turned dark when members of the Chhatra League [the student wing of the ruling Awami League party] and police started murdering and brutalizing protesters.

Police brutality is not new, but seeing over my phone these events unfolding in the city I was born in is terrifying. I can’t get the image out of my head of police throwing a dead body off their vehicle and running over it. My cousins and family in Bangladesh posted videos of students being shot and beaten by police and slashed with machetes by the Chhatra League. Witnessing such atrocities near your home is horrifying. This was right before the Internet was cut off, and I couldn’t contact my family or friends in Bangladesh for a while.

Though I am upset and scared for their safety, I remember that our people have had resistance in their blood since 1971. They will fight through this for their rights and their people.

—Muzaina Nushma, 17, USA

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The past two weeks have been a harrowing experience. Being a young person in this country, we no longer feel safe. My friends and I have found ourselves hallucinating gunshots and the sounds of helicopters. This isn’t just our imagination; we have all experienced it in the past few weeks—we heard gunshots close to our homes and had helicopters flying over our houses with searchlights.

The unprecedented six-day Internet blackout, cutting us off from information and taking away the freedom to express ourselves, is a shock to our generation. To lose so many young lives, so violently, while being denied access to information is a trauma we will never fully recover from. All of this has left an indelible scar on our collective consciousness.

This crackdown on student protesters has seen thousands of people arrested across the country. In a particularly striking case, a 17-year-old was ordered to a weeklong police detention, which was canceled only after public outrage.

As a young journalist, I also cannot forget the three journalists killed while reporting. How does one continue to work and live in this climate of fear?

Above all, it’s the tremendous loss of lives, taken without dignity, for which the state refuses to accept responsibility. The spirit of the movement is now a powerful force—united in grief, anger, and determination—to bring justice for the countless lives lost.

—Usraat Fahmidah, 20, Dhaka, Bangladesh

As a Bangladeshi-born youth currently living in the USA, I am devastated. Bangladesh has always been known as a country filled with corrupt politicians, but for that to be the reason behind so many deaths since our independence—especially younger children and students just like me—was something I had never expected.

Bangladesh had gone into a complete blackout. I have relatives who we couldn’t contact. Every article written on Bangladeshi websites and any possible communication method was completely futile. It is only recently that the country has had Internet access, but it could be disconnected at any time.

I noticed that my community, especially other Bengalis living in the United States, lacked thorough knowledge of the situation and hardly engaged. My friends and I felt passionate about advocating, so we opened an international call for action called ‘Shadheen Bangladesh’ on Instagram, researching and updating the page with new information each day since July 15.

Since then, the protests have even spread to Times Square. As a Bengali, I have never been so proud of myself, my friends, and my community. As the next generation, we consistently prove ourselves capable by using our voices for the greater good.

—Addrita Biswas, 16, USA

More from The Nation

The People vs. ICE The People vs. ICE

Across the country, neighbors are working together to protect one another from Trump’s immigration crackdowns.

Puerto Rico’s Mothers Against War Turn to Revolutionary Love Puerto Rico’s Mothers Against War Turn to Revolutionary Love

Formed to oppose the Iraq War, Madres Contra La Guerra have now spent decades trying to end Puerto Rico’s role at the center of the US war machine in Latin America.

A Minneapolis Teacher Wants the Whole Country in the Streets A Minneapolis Teacher Wants the Whole Country in the Streets

Dan Troccoli, a public middle school teacher, says everyone should start “emulating” Minneapolis’s resistance to ICE and the Trump regime.

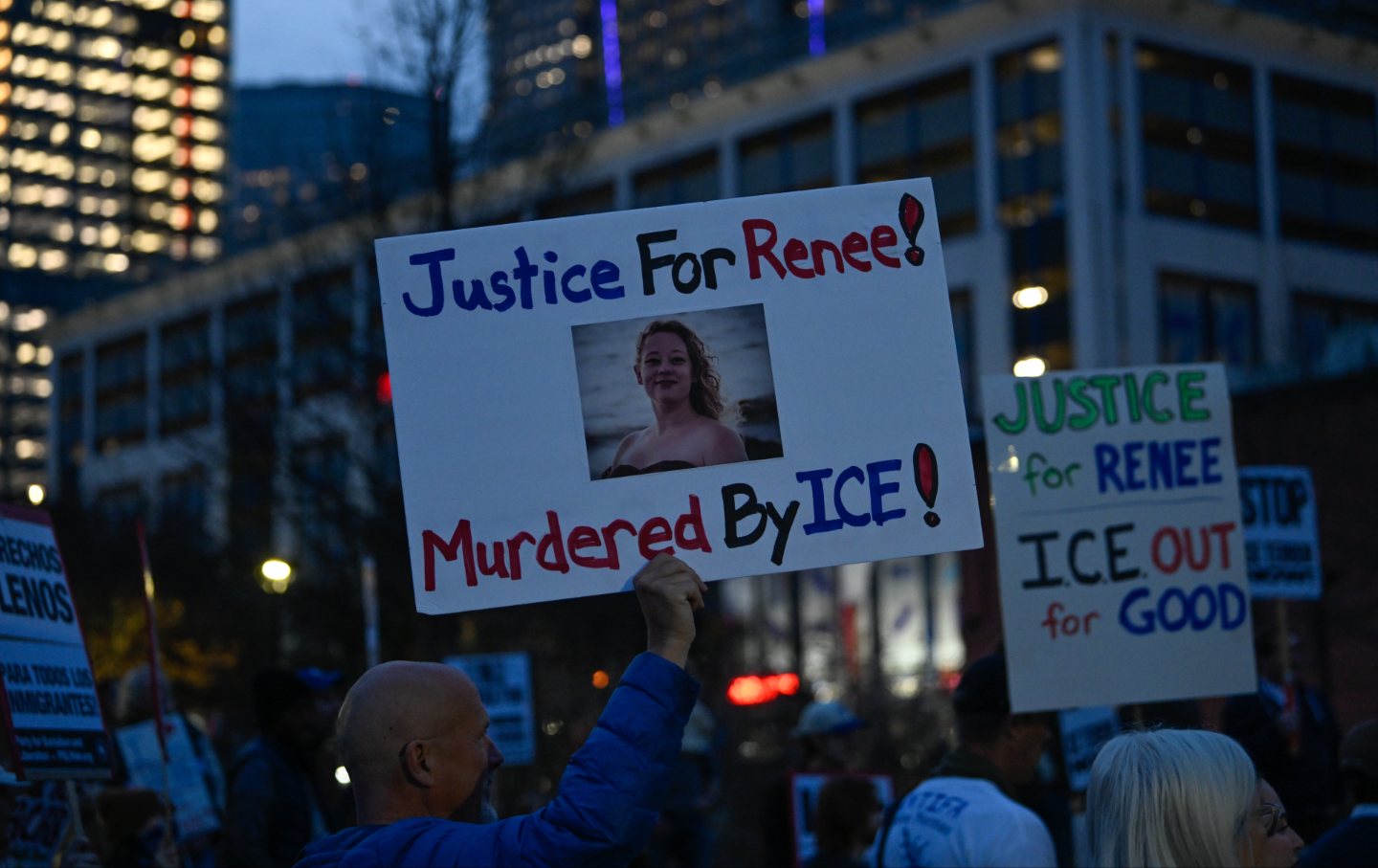

Let’s Make Renee Good the Last Person That ICE Kills Let’s Make Renee Good the Last Person That ICE Kills

We can turn the tide against Trump—but only with mass action and courageous leadership.

Liberals Think Antifa Isn’t Real. But It Is—and It Knows How to Win. Liberals Think Antifa Isn’t Real. But It Is—and It Knows How to Win.

To protect us all from the violence of the Trump administration, we must defend antifa.

Want to Stop ICE? Go After Its Corporate Collaborators. Want to Stop ICE? Go After Its Corporate Collaborators.

ICE can’t function without help from the private sector. So we should force the private sector to stop helping.