It’s not as head-turning a rebellion as the one that helped democratic socialist India Walton, in her first run for office, beat a four-term incumbent mayor in last summer’s Democratic primary.

But it’s a lot of the same people, a lot of the same energy. And community activists elsewhere would do well to examine what’s happening here.

The current uprising has to do with redistricting the city’s Common Council to comport with 2020 US Census numbers, which showed Buffalo gaining population for the first time since 1950.

Redistricting is not a sexy topic. At its best it is wonkish, involving complicated formulas and tests for compactness, population deviation, and racial balance. At its worst it is corrupt—an opportunity for once-in-a-decade deals between politicians seeking to protect themselves and their allies from challengers.

Eleven years ago, when Buffalo was still losing population, a pair of city councilmen (at the time, all members of the city’s Common Council were men—as they are today) struck such a deal, with the approval of their fellow legislators.

The longtime representative of an East Side district that had been hemorrhaging people for decades needed to add voters to his district—preferably white voters. The Common Council president, a Black pastor, had some he was happy to lose. Plus, the pastor was living in a waterfront condominium that was outside the district he represented.

So, in 2011, the council redrew those two districts, connecting a swath of depopulated, largely Black East Side with a densely populated, mostly white West Side neighborhood, via one-block-wide corridors, one of which strained to attach the pastor’s condominium to his district.

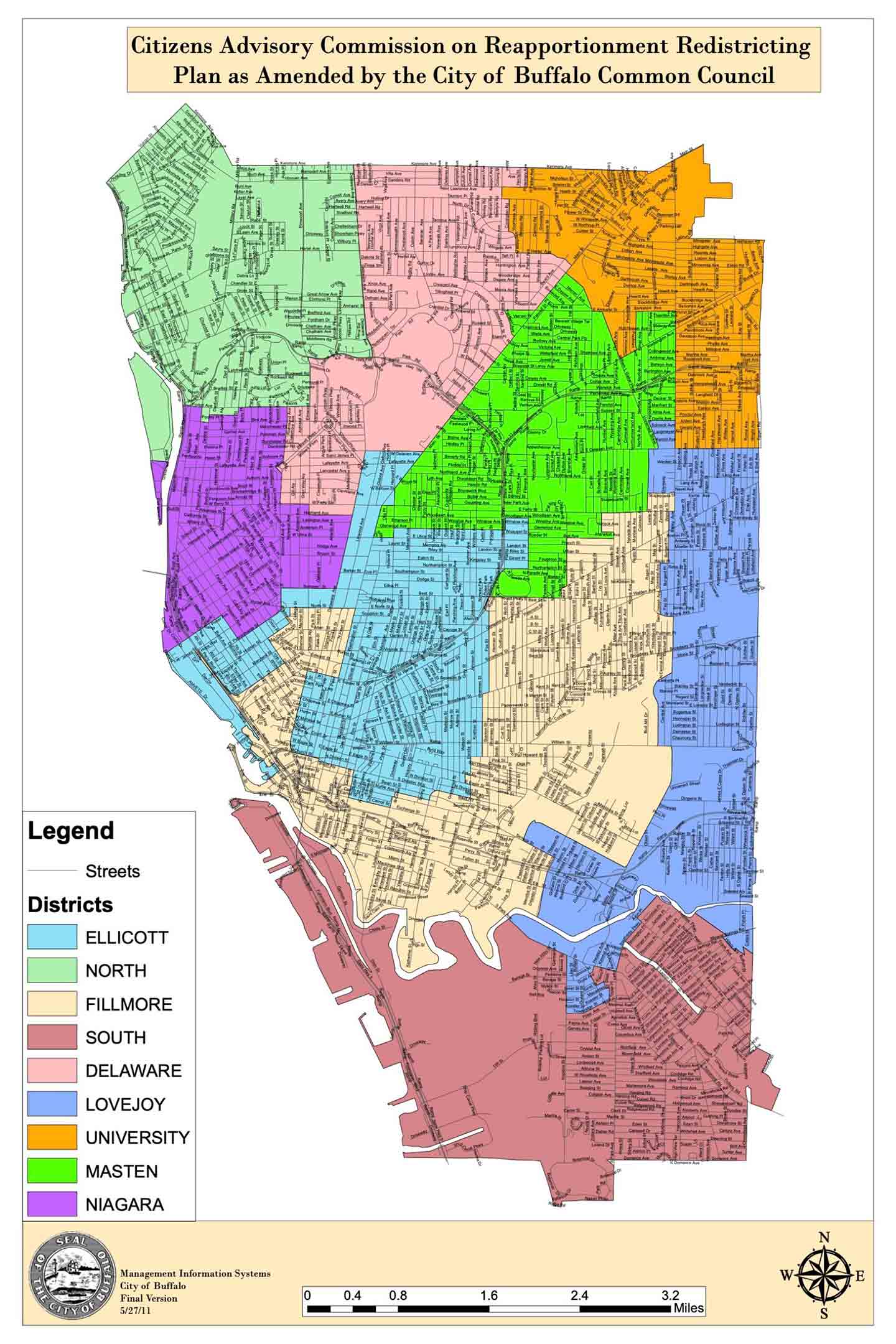

You don’t have to know a thing about Buffalo or its neighborhoods to look at this map and recognize a textbook case of gerrymandering:

The central, light-blue district is Ellicott, represented by Council President Darius Pridgen. The tan district that surrounds it is Fillmore, represented at the time by David Franczyk.

Franczyk has since retired. Pridgen no longer lives in that waterfront condo. The political underpinnings of that deal have vanished.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

And yet, when a redistricting commission empaneled by the council earlier this year unveiled its proposed new map in May, there were few changes. Fillmore still resembled a bird of prey, wings spread wide, swooping out of the sky; Ellicott District, while it shed its egregious waterfront annex, continued to sport strange peninsulas.

It was an incumbent protection proposal, designed to keep councilmen in the districts they know, with the voters they know, for the next 10 years—and most particularly next year, when all nine councilmen must run for reelection. It keeps the West Side home of Franczyk’s successor, Mitch Nowakowski, within Fillmore District.

This is hardly unique to Buffalo. Everywhere across the country, where legislators direct the redistricting process, the results tend to cater to incumbents first, communities second. And, no doubt, the bones of many long-irrelevant political deals are entombed in the legislative maps of other cities.

“Guided by the dead hand of the past,” as a local election lawyer put it, encouraging Buffalo’s councilmen to return to the drawing board.

But what happened here next is unusual. Anywhere. And maybe worth learning from.

The council-appointed commission held a public hearing on the evening of May 18, four days after a teenage white supremacist murdered 10 Black people in an East Side supermarket (Ellicott District, if you’re wondering). Two members of the public attended. Just one spoke, proclaiming the commission’s proposal “an excellent map,” because it reunited his block club in one district. It had been split in two in 2011.

The person who didn’t speak was Dr. Russell Weaver, a data geographer with Cornell University’s International Labor Relations School. Weaver was once a legislative staffer for Buffalo’s Common Council. He served on the 2011 redistricting commission that produced the gerrymandered map perpetuated by the proposal he’d just seen. He had been the lone vote against it.

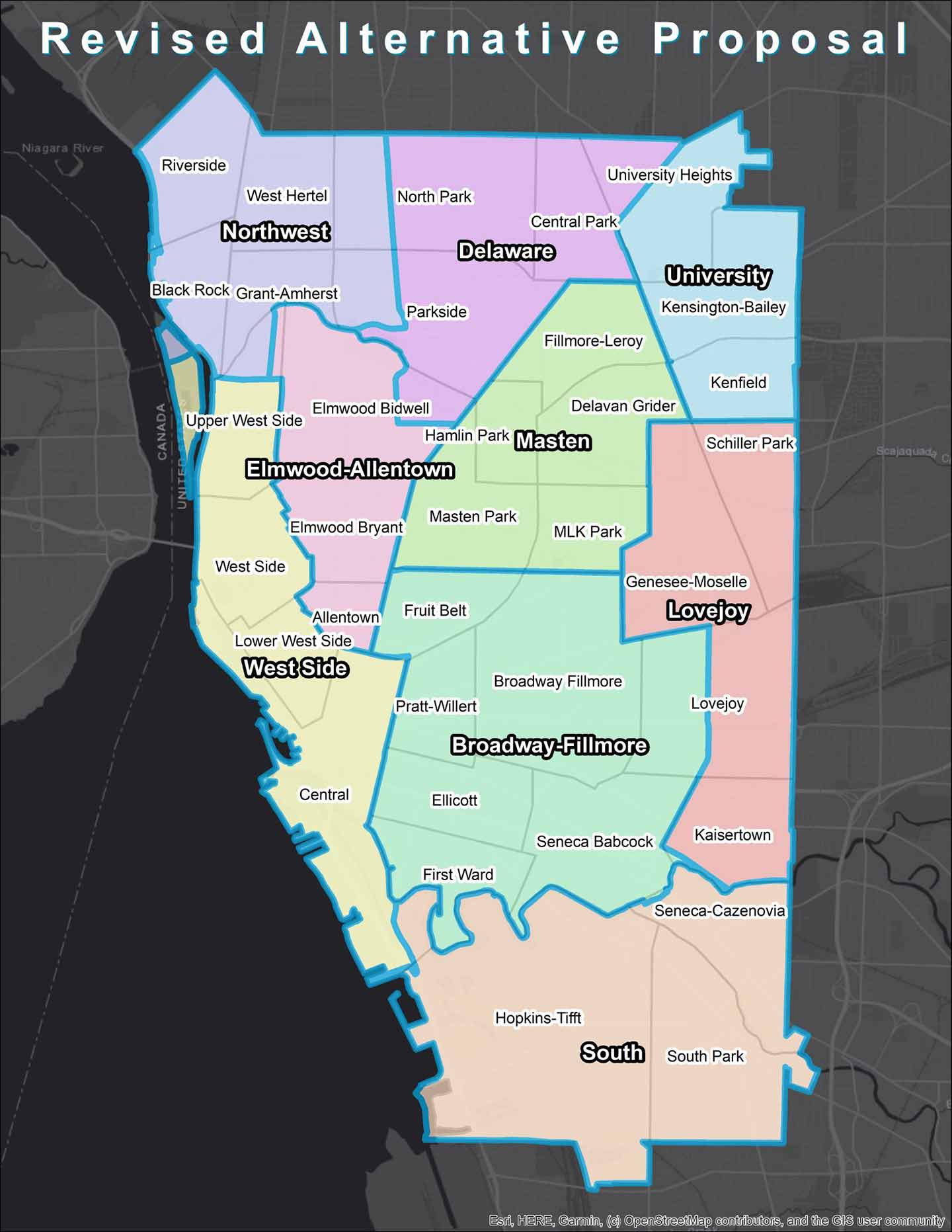

So Weaver went home, booted up his computers, and started drawing maps. Then he began posting his work on Twitter. He shared the criteria he was using: compactness, which means a minimum of weird shapes and protuberances; keeping neighborhoods, as defined by city planners for policy purposes, intact; promoting racial equity. He shared fine-bore Census data to show what he was doing.

His efforts were soon abetted and amplified by Our City Action Buffalo, a coalition of activists who were deeply involved in Walton’s mayoral campaign last year. Our City Action packed a June 28 public hearing with speakers, more than 100 of them. All opposed the council’s redistricting plan—which had been constructed behind closed doors with no public input. All supported the alternative redistricting plan created by Weaver and promoted by Our City Action.

Plenty were angry that the first public hearing had been held while the city was reeling from tragedy, and the second on the day of a primary election.

“This tells us everything we need to know about how little they respect or value our input,” said Harper Bishop, a leader of Our City Action. “As their constituents, we—everyday Buffalonians—should be informed, engaged, and encouraged to participate.… but they are not even pretending to listen.”

No one defended the council’s preferred plan, not even the councilmen, who looked miserable under the barrage of criticism.

The rebukes were brutal and unrelenting. The commission’s May 18 hearing had lasted eight minutes. The council’s June 28 hearing went on for two and half hours.

Faced with this unexpected rebellion, the council chose to rush forward. Two days after the brutal public hearing, it announced a special session on Friday morning, July 1, to adopt its preferred plan.

But Our City Action shamed, threatened, and cajoled, inundating members’ offices with phone calls and e-mails, until—in the middle of a press conference on the steps of City Hall where activists decried members’ tone-deafness—the council canceled the Friday session.

“The Council has decided to delay this meeting in order to provide more time to review and consider the details associated with the proposed maps and public input,” Pridgen, the council president, said in a statement. “We will be rescheduling this meeting at a future date to be determined.”

The special session has not been rescheduled. No new public hearings have been announced. Council members did not address the issue in last week’s meeting of the Legislation Committee, where their preferred plan lay tabled.

Here’s the part to which communities in other cities might pay attention: As the council stewed in silence, that was a point for the activists, but hardly the match. So Our City Action kept moving.

Over the long Independence Day weekend, the activists processed feedback generated by Weaver’s alternative redistricting proposal, including responses from councilmen. Then they revised the proposal accordingly.

In other words, Our City Action cast themselves in the role of an actually independent, citizen-led redistricting commission.

With the council lost at sea, community activists grabbed the rudder.

Weaver’s first plan was better than the council’s on compactness, keeping neighborhoods intact, and promoting racial equity. The revised plan is better still. Again, one need not know Buffalo or its neighborhoods. The new map just looks better:

According to the city charter, the council must adopt a redistricting plan by the end of this month. The mayor will then hold a public hearing of his own, before sending the adopted plan to the county board of elections. The map adopted will determine the districts candidates run in next year.

Last Friday afternoon, July 8, the council announced that it would meet and vote on its redistricting proposal on the afternoon of July 12. Once again, the Our City Action coalition scrambled over the weekend to mount resistance: press conferences, phone and e-mail campaigns, media appearances.

It is likely the council will ignore the insurrection, adopt its preferred redistricting plan (or something close to it), then head off on vacation during the council’s August recess, leaving staffers to field angry phone calls and e-mails. They may have lost the rudder for a moment, but it’s still their ship.

And remember, India Walton shocked regional politics by winning last June’s Democratic primary. But she lost in the November general election. The powers of retrenchment are strong.

However, the councilmen know potential challengers are ready to beat them around the ears with this issue in next year’s election cycle. Those challengers will have support. The Buffalo News’ editorial board—not usually a friend to progressive activists—lambasted the council and wholeheartedly endorsed the Our City Action alternative. More than 800 people have signed a petition in favor of it. Block clubs and neighborhood business associations have jumped on board, too.

Last week, Weaver made an appearance on a weekly radio show hosted by Partnership for the Public Good, a good government group, to discuss the Our City Action Plan. He was joined by Jillian Hanesworth, the city’s first officially designated poet laureate.

Hanesworth made the threat explicit.

“We have to take note of what our elected officials’ priorities are,” she said. “And if we don’t fall on the list, they have to go.”

Editor’s Note: On the evening before the hearing scheduled for July 12, after this article was in press, the Common Council once again postponed the scheduled vote.