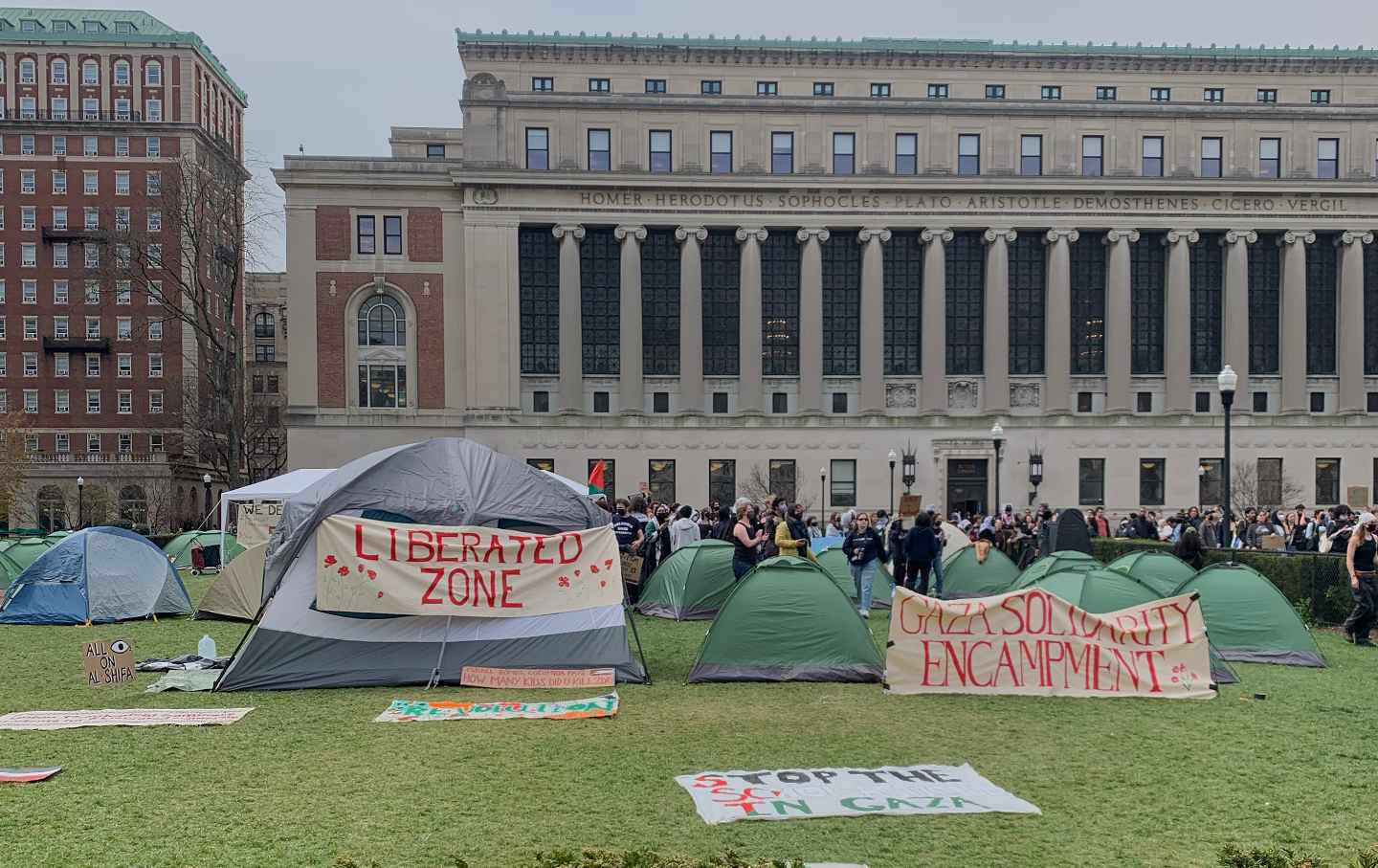

Inside the Gaza Solidarity Encampment at Columbia University

Hundreds of peaceful protesters began occupying the campus on Wednesday to demand that the university divest from Israel. The next day, the school sent in the NYPD to arrest them.

Around 4 am on Wednesday, hundreds of Columbia University students set up tents on the East Butler lawn, establishing what they called a “Gaza Solidarity Encampment” in protest of the university’s role in helping fund the war in Gaza.

The occupation, organized by the Columbia University Apartheid Divest coalition (CUAD), Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP), and Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), had been planned for months. The encampment was an escalation of previous pro-Palestine actions, designed to echo the university’s history of protest. “Columbia University has a rich legacy of student activism, from Vietnam War protests in 1968 to being the first Ivy League school to divest from Apartheid South Africa in 1985,” wrote CUAD on Wednesday. “The Gaza Solidarity Encampment will remain until Columbia University divests all finances, including the endowment, from corporations that profit from Israeli apartheid, genocide, and occupation in Palestine.”

The peaceful occupation began the same day Columbia President Minouche Shafik testified at an antisemitism probe by the US House Committee on Education and the Workforce. During the hearing, Representative Ilhan Omar questioned Shafik about an apparent chemical attack by two Israeli students at a Gaza solidarity rally on campus earlier this year. In January, pro-Palestinian protesters reported physical symptoms consistent with chemical inhalation and sought medical attention. At the hearing, Shafik announced that the perpetrators had been suspended, though she has yet to publish a statement about the chemical attacks or reach out to those affected, according to Columbia graduate student Layla Saliba, one of the victims.

Seda, a CUAD member who spoke to The Nation using a pseudonym, said that the congressional hearing wasn’t the driving force behind the encampment: “Even if the hearing were not happening, we would have had some sort of escalation because there’s been no material change in the university stance since we’ve started organizing against the genocide.” Another protester, Isra Hirsi—the daughter of Representative Omar—said that the hearing was helpful for visibility: “Not only can we situate ourselves in the current moment, but we can also take advantage of the media presence, of the pressure being put on Shafik and the board of trustees.”

The university was locked down. Only Columbia ID holders were able to access school property, with police, campus security, and private security stationed at every entrance. Members of the National Lawyers Guild, wearing neon green hats, had arrived that morning to defend the students’ right to protest. By the afternoon, hundreds of other Columbia students showed up in solidarity with the occupation, often bringing donations and supplies. “There were a lot of reports that people were freezing in the morning, and I know that there’s supposed to be rain later tonight, so I got emergency camping blankets from a nearby hardware store. I figured they would be more effective than regular blankets, in case conditions get really wet later,” said Roxanne, an undergraduate student.

While she did not join the encampment for fear of disciplinary action, Roxanne said that “this cause is really important to me as an anti-Zionist Jew. I wanted to help the people who were brave enough to put their bodies and academics on the line.” Other supporters went to the dining halls to bring armfuls of coffees for the protesters. And when Maryam Alwan, an undergraduate in the encampment, mentioned having dry eyes, one student rushed to a nearby Duane Reade and returned with eye drops in hand.

Counterprotesters also stood around the lawn, waving massive Israeli flags. But those in the encampment seemed unfazed. Some demonstrators ate slices of pizza; others knelt for the dhuhr prayer. “We come from a long lineage of students and activists who stand up for justice,” observed Seda. “I want the world to stop diminishing our struggle as wokeness or some political fad. It’s not. People here are closely tied to their commitment to justice.”

The evening was filled with false alarms. Around 9 pm, rumors of an NYPD sweep sent organizers into a frenzy. “Columbia University is once again threatening to unleash the NYPD—killer cops who were trained in Israel—on their own students. But we know they cannot come for us when we stand together,” said graduate student Catherine Elias. A few minutes later, another demonstrator took the bullhorn: “[The police] are afraid. Their backs are against the wall,” he said. “Where the fuck are they?” he asked the encampment, prompting cheers.

That evening, Vice President and Dean of Barnard College Leslie Grinage began handing out notices to protesters in the encampment, telling them to disperse or face interim suspensions. “I’ve never been arrested before, so it is a little scary,” said Alwan. “But no matter how frightening arrest may be, what people are experiencing in Palestine is way worse.”

As the first day turned to dusk, picketers and demonstrators remained energized—chanting, dancing dabke, and beating drums. When the clock struck 4 am on Thursday, the occupation, against all odds, had lasted 24 hours.

“I am feeling empowered…by our resilience in the face of tremendous crackdown and repression,” Daria Mateescu, president of Columbia Law Students for Palestine, told The Nation. One of their demands had already been met, she said. The administration announced that it would now provide financial transparency for investments with the University Senate executive committee.

This early concession from Columbia initially gave the organizers hope. “We saw the student movement win in 1968. We saw the student movement win again with Columbia’s divestment from apartheid South Africa,” said Elias. “And we know that the student movement will win again today.”

But on Thursday, just before 10:30 am, three Barnard students—Isra Hirsi, Maryam Iqbal, and Soph Dinu—were told that they had been suspended for their participation in the encampment. Standing on the sundial, Iqbal informed picketers and demonstrators that she had been evicted from her housing. “Apparently, Barnard’s arbitrary rules take precedence over international law,” she said. Spectators’ voices crescendoed as they chanted “shame!” “Being suspended for Palestine is an honor,” said Iqbal. “The more they try to silence us, the louder we will get.”

Both Hirsi and Dinu mirrored Iqbal’s resolve. “I am not going to leave. I will have to be moved by force,” said Dinu. “We will not be backing down,” said Hirsi. “The least we can do is stay here and hold it down for Gaza.”

Only a few hours later, around 1 pm, Shafik authorized the NYPD to sweep the encampment and arrest the protesters to uphold the “safety of the community,” according to an e-mail sent to the student body. Police, some clad in riot gear, entered while demonstrators sat in a circle, linking arms—many chanting, a few sobbing, others directing their gaze past the police and into the sea of keffiyehs and Columbia students surrounding the encampment.

Some frantic onlookers pushed through the crowds to catch a glimpse of their peers’ being arrested. “I feel sick,” said one student as she watched police escort her best friend—the last person to be detained—off the lawn. Others were elated. “It’s about time the NYPD did something,” said one observer.

Even as the NYPD forcibly removed her from the encampment on Thursday, Elias refused to turn her body away from her fellow protesters. She walked out of the lawn backward, still chanting along with them.

By 2 pm, over 100 people—including at least two legal observers—had been arrested, restrained with zip ties, and marched onto police buses. The university, according to CUAD, also dumped protestors’ belongings in a nearby alley. Hundreds of enraged students and spectators—as well as Cornel West and Mohammed El Kurd, The Nation’s Palestine correspondent—hopped the fence around the West Butler lawn to resume the occupation. Seda, the CUAD member, stood in the center and announced the newly formed protest “in solidarity with our comrades.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In a statement ahead of the hearing, CUAD accused President Shafik of curtailing free speech and fostering “campus McCarthyism.” For students, the arrests only made this more clear. “The administration has ignored our countless pleas to engage meaningfully with students, opting instead to continue down a path of surveillance, oppression, and authoritarian policies,” wrote the editorial board of the Columbia Daily Spectator. “Why does a university that flaunts its ‘storied history’ of successful student activism seek to contain and suppress student mobilization?”

Because they were suspended by the university, arrested students were treated as trespassers and issued summonses. The coalition is now demanding “full amnesty, no further arrests, and the dropping of all charges for all students disciplined for their involvement in the encampment or the movement for Palestinian liberation.”

The destruction of the encampment saw the largest mass arrests of student protesters in recent months. Despite the tough response by the university, students were not deterred. “Columbia may arrest our organizers; it may tear down our encampments; but it cannot dampen our commitment to divestment of all finances,” said CUAD. “We’re still here,” said Leila, one of the students who continued protesting after the arrests. “We still care about the movement; and we’re going to show the occupiers that their encampment was not done in vain.”

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation