The Cop City Defendants Are Done Being Silent

Sixty-one people are facing RICO charges from the state of Georgia for their activism. Here’s what some of them have to say about their case.

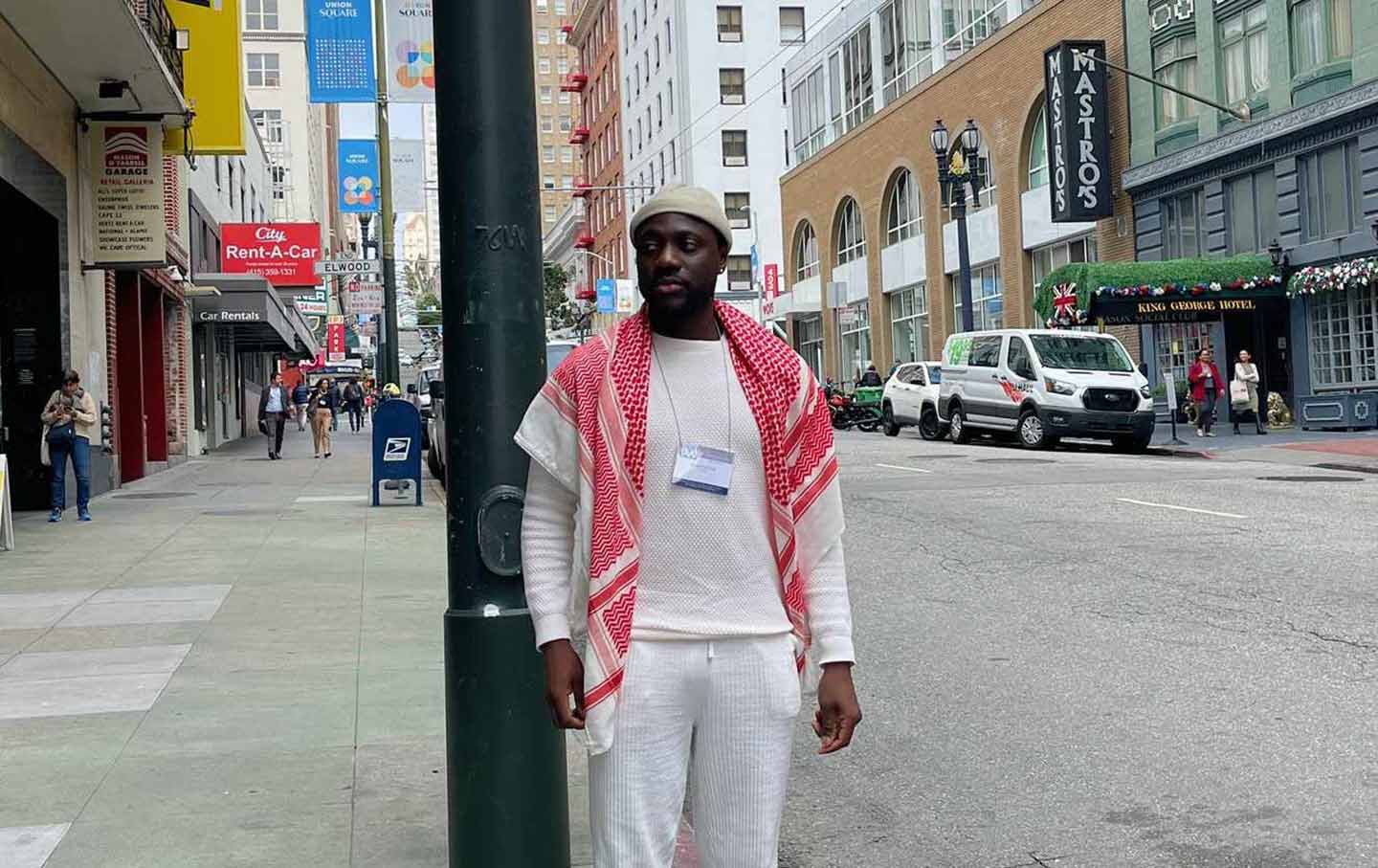

A protester at a vigil in Atlanta, Georgia, commemorating the life of environmental activist Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán on January 18, 2024. Tortuguita was killed by Georgia State Troopers a year before, on January 18, 2023, during a raid on a Stop Cop City encampment.

(Collin Mayfield / Sipa USA via Getty Images)Julia Dupuis thinks it’s a bit absurd that they’re wearing an ankle bracelet right now, given that all they were doing in Georgia was putting up flyers.

The flyers, which they posted on mailboxes in a town outside of Atlanta, were protesting the shooting of Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán, a young activist whose killing by Fulton County deputies in 2023 turned them into a martyr in the fight against the Atlanta-area police training complex now known all over the world as “Cop City.”

Dupuis never thought of flyering as a particularly radical act. “Distributing flyers, putting up posters, peaceful protesting where you take to the street… it’s just spreading information to raise awareness—that’s like the most basic act of protest,” they say.

But the state of Georgia, which is as hell-bent on building Cop City as its opponents are on stopping it, had other ideas. And so, in September, Dupuis and 60 other Cop City activists found themselves indicted under Georgia’s version of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, a law purportedly designed to punish organized crime syndicates.

The indictment was immediately condemned by legal scholars, who described it as a gross overreach of state power, and it came at a tumultuous time for the state and county, as former President Trump faces another Georgia RICO case for interference in the 2020 elections.

But for the “RICO 61,” the ongoing legal battle is not just theoretical—it’s their daily reality. As they await a potential June trial, many have been struggling to reckon with the ways state repression has put their lives on hold—in some cases, for acts as innocuous as flyering or sharing the cost of food. They’ve also noticed what’s often been missing in coverage of their case: their own voices. That silence, according to some of the RICO indictees, is what the state wants from them—and they’re no longer willing to comply.

Or, in other words, they’re like Dupuis—sitting around with an ankle bracelet, time on their hands, and a need to tell their story.

“Speaking out is a really contentious and dangerous thing to do,” Dupuis says from their parents’ home in Massachusetts. (While defendants must return to Atlanta for trials, some were required to leave the state while the case is ongoing). “The prosecution loves to use people’s words against them. And so silence is the safest option. I reached a point where I didn’t want to take the safest option anymore.”

Whether it’s speaking out about their treatment while incarcerated—in the wake of the arraignment, codefendants report being denied food and water and being sexually harassed by guards in jail—or just the general terror of being subjected to a campaign of state repression, many feared that talking to the media would increase their persecution.

“I didn’t speak out for the longest time because I was terrified, to be completely honest,” says Dupuis. “I got out of jail, and I was just stunned. I was in shock. I was terrified that if I spoke out, I’d make myself a target in some way, that I’d signal to the state that I was more of a threat.”

This fear is understandable given the specifics of the indictment. It labels the Cop City activists “anarchists” and alleges a wide variety of crimes, from criminal trespass to domestic terrorism. Prosecutors also allege that, among other things, using a “burner” phone shows criminal intent, a sign of just how expansive the indictment’s scope is.

But as the months went on, the silence began to feel unbearable for some of the defendants. Dupuis felt “voiceless.” This need to take back their own narrative also motivated another codefendant, Peatmoss. “The government punishes folks who work for a more just and kind world—we need more folks to know that. Even when all you want is a world where cops don’t hurt the people they are supposed to protect,” they say.

Another defendant, Hannah Kass, a 30-year-old PhD student at the University of Wisconsin, sees going public as an important political tactic alongside their ongoing legal defense. “The prosecution wants everyone to think we’re violent terrorist racketeers. They’re doing more than we can imagine, or even have capacity for, to embed that narrative into the public eye, and public mind,” she says. “It’s important to me that we also speak our narrative and our side of the story to the public, and make sure people know who we really are and that we’re human. We are just life on earth defending itself.”

Making this point clear, Kass says, is an important part of refuting the state’s narrative around why Cop City is necessary—a narrative that says police are essential, and one that promotes the “pedestalization of property as more important than life itself, more important than human life, or nonhuman life.”

“That’s playing out in the statutes they’re using against us, in the indictment, and just in general in the interactions between the state and the movement over the course of these three years,” Kass says. She notes that when she and the other codefendants were taken to jail following the arraignment, they were met with an increased police presence beyond normal jail guards in the jail—signaling to her at least that the state considers them a threat.

This is a narrative that she and other codefendants want to refute. “There’s so much love and joy, and this movement is actively about that,” notes fellow codefendant Charley (who declined to give their last name for security reasons). “I think one of the things that really draws people to this movement is that being together, we’ve created this shared sense of direct joy in a way that deeply moves anyone who’s ever had that kind of experience—it not only ignites us, it unites us. It feels really good to do things with your friends, loved ones, comrades, people you don’t even know! We can do great things together.”

As their cases have slowly inched forward, however, several of the RICO 61 defendants say they are struggling to cope. Most if not all are under orders to not speak to each other while the case is ongoing—isolating them from the sense of community that is at the core of their fight.

For some, these consequences feel just as severe—if not more so—than being denied job opportunities or having their bank accounts closed, which also have occurred as a result of the charges. “My life has been completely put on hold,” Dupuis says. “I’ve been completely ripped from my community, I’ve been completely isolated.”

Being unable to return to the forest they have sacrificed to protect is also a blow. Kass is working on a geography dissertation that involves her work in the forest. “My bond condition for RICO, one of them, is that I can’t return to the forest,” she says. “I officially cannot return to the forest until after this case is resolved.” Nevertheless, she is optimistic: “I have faith that we will win, and I will return to the forest at some point.”

For Kass, the indictment’s overreach illustrates the dangers that the Cop City movement poses to the system that is cracking down on her. “The forest has been, and has become, a place to experiment with possibilities beyond property and beyond enclosure and beyond police,” she says. “What they’re trying to accomplish, I think, is to criminalize not only this movement, not only the Stop Cop City dissent, but a way of life and a way of relating to one another that is antithetical to property and dispossession. That’s what they’re trying to ultimately create, through creating a more militarized police force, the better to violently exclude people from what should be all of ours.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In the face of this narrative, Kass, along with a number of codefendants, wants to make clear that the state is the real threat—and that their fight is one that everyone should care about.

“I think they’re making an example out of us to try to send a message to everyone else, a really chilling message that if you speak out against this, if you fight for what’s right, what happened to us will happen to you,” says Dupuis. “I don’t want to let that fear silence me, because I know that that’s exactly what they want.”

As time passes and their ability to protest is curtailed, the codefendants are concerned about maintaining public support—something they see as essential to challenging a state apparatus that doesn’t exactly have their best interests at heart. In the wake of the indictment, as well as the US government’s support for Israel’s military campaign in Palestine, public attention around Stop Cop City has grown. Defendants say it’s been heartening to see people around the country rally behind their struggle, though some worry about the long-haul fight. Many have their own robust support teams, but, they point out, they are still going up against a system that is far more powerful and resourced.

“It’s been amazing how all sorts of people have come forward to offer Peat support—they have so many people in their corner,” says Lance, a friend of Peatmoss. Peat’s defense committee has helped them with fundraising for trips to Atlanta for court dates—a hurdle several codefendants mentioned—as well as helping with legal defense, learning from other political defendants in similar situations, and providing emotional support.

But even with support systems, it can be difficult to feel that your story is subject to the whims of other peoples’ attention spans. “As someone who’s being criminalized, it’s hard when people get bored or burn out on your struggle, and you have to live it all the time,” Kass says. “It didn’t just stop happening for me, it didn’t stop being crazy, or having a real impact on my life. Seeing the impact it will have on the world, and people just forgetting about it.… I couldn’t relate to that.”

Kass says that for those who want to join the struggle, Atlanta jail support is often looking for remote volunteers, and local bail funds are accepting donations. A number of codefendants are also currently soliciting donations for legal support. She has been helping to set up “know your rights” trainings at her university. “Being able to replicate and ripple out those kinds of anti-repression infrastructures only happens as people plug in and gain that experience of actually operating those infrastructures,” she says. “It’s super important and super helpful.”

Charley, who is from Atlanta, also notes that the activists’ call to action extends beyond the borders of the forest, and the state of Georgia. “These issues are bigger than any one place. These issues matter to anyone who cares about environmental justice, about anti-oppression work in general, about being anti-racist. If you care about any of this stuff, then you care about the fight to Stop Cop City and save Weelaunee. You can be not from here and still have an absolutely legitimate claim to be a part of this—because these problems transcend locality.”

This sense of universality is what keeps many of the RICO 61 going, despite the uncertain future. “Our activism is out of love and care for the world, not out of wanting to see it die—that’s actually a projection on the part of the prosecution because they want to see our people die, they want to see our trees die,” says Kass. “They are pushing a world of death. I want to speak to the fight for life.”

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation