The Responsibility of Culture Workers to Help Stop the War on Gaza

Researchers, writers, and scholars can identify the institutions that provide ideological cover for Israel’s violence and then intervene to stop them.

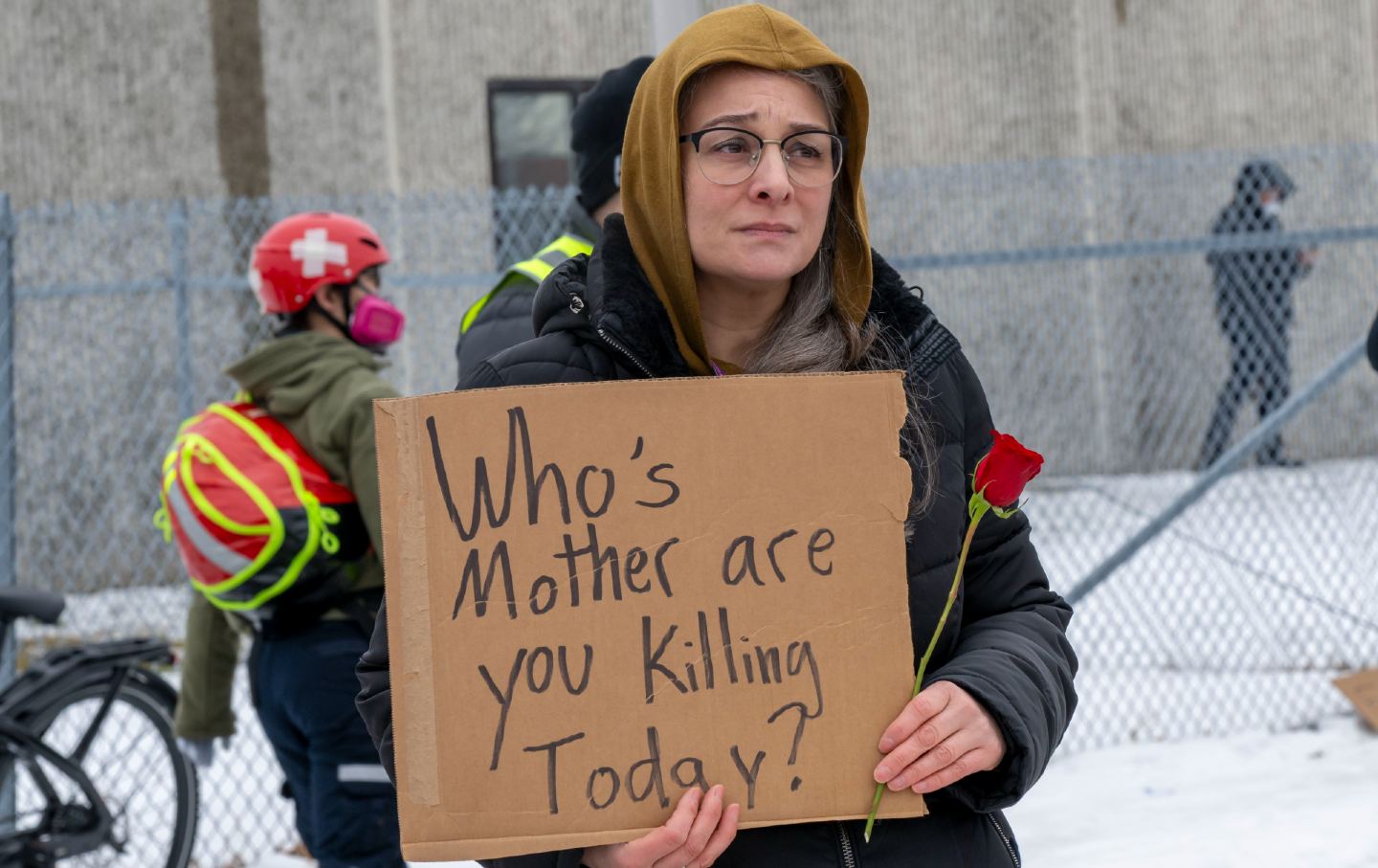

Pro-Palestine protesters gather outside the offices of The New York Times to challenge the newspaper’s coverage of the Israel-Gaza war during a global call to “Strike For Palestine” on December 11, 2023, in New York City.

(Michael Nigro / Sipa / AP)In one of the songs in Brecht’s play The Mother, a character organizing to undo a coercive and brutal regime names the resources that his opponents have: prisons and the people paid to make sure they’re filled with dissidents; deadly munitions and the people paid to fire them into crowds; newspapers and the people paid to write for them and “who blacken our name and reduce us to silence.” Brecht sketches a system in which the production and circulation of ideas plays a critical, though not primary, role in making extreme violence possible.

If media workers, researchers, writers, and other culture workers abet war, we therefore have a responsibility to stop it—especially if, as Raz Segal argues in Jewish Currents about Israel’s war on Gaza, it involves a “textbook case of genocide.” Perhaps counterintuitively, that role is not just to speak with moral clarity about unconscionable violence in high-profile places. Solo expressions of noble conscience rarely accomplish anything on their own, however poignantly phrased. Instead, our contribution must be a part of a mass, organized, strategic attack on the power structure that currently guarantees Israel’s ability to wage war and maintain occupation and apartheid.

The challenge of this organizing project, somewhat escalated among people who are trained to think of ourselves more in terms of our individual talent than our collective capacity, is to avoid both over-aggrandizing our role (say, as people gifted with special clairvoyance, uniquely capable of representing collective suffering) or falling into the trap of what Ruth Wilson Gilmore calls disabling modesty. By this phrase, Gilmore identifies the pretense that highly trained workers may make of not having particular talents to contribute to liberation movements from the specific positions that we occupy. Culture workers have, for instance, specialized training—research and investigation; making sense of and communicating dense and confusing information; uniting a disparate audience around a clear purpose and direction; asking useful questions and testing assumptions inside organizing spaces in the goal of determining what is to be done—that will be critical in the effort to put an end to the war in the near term, and in the long term end long-standing international support for the blockade of Gaza, settler pogroms in the West Bank, and the apartheid regime inside the 1948 borders.

Why is it not enough for culture workers to condemn the war in high-profile venues? Measuring public opinion alone, the movement against the war on Gaza is highly popular, but deeply disempowered. A 70 percent supermajority of the US supports a cease-fire, including a majority of both Republican and Democratic voters. But the US government still foots the multibillion-dollar bill for Israel’s war crimes—which include the intentional targeting of civilian infrastructure, launching airstrikes at schools, invading Al-Shifa Hospital under the false claim that it hosted a military base, and repeatedly bombing the Al-Jabalia refugee camp. A small, though growing, minority of democratically elected representatives at the federal level—the actual decision-makers whose votes secure or prohibit military aid to Israel—have publicly called for a permanent cease-fire. In other words, while people who oppose war and genocide need to hold the line, we don’t actually need to win the battle for public opinion against the war—that is already decisively on our side. Instead, we need to understand the power structure that makes a small number of decision makers decide to facilitate the war in Gaza and that insulates them from the consequences of their actions. And then we need to use that knowledge to cause a greater crisis for them than the one they fear from our opponents.

Cultural institutions—media, universities, museums, literary centers—form one element of the power structure that keeps the US government solidly in support of Israel’s massacres. Biased reporting from marquee news outlets like The New York Times and CNN gives Israel much-needed cover to continue dropping bombs on civilian targets, sniping patients in hospitals, and cutting off food and fuel from one of the world’s most densely populated areas. Cultural organizations—like 92Y, which has hosted far-right Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—have for a long time laundered Israel’s image to a base of liberal Democratic voters who believe themselves to be anti-racist moral actors on the right side of history. Even more critically, several US universities collaborate with Israeli universities on research and other programs; Cornell University, for instance, jointly runs a research program with Haifa’s Technion, which boasts close ties with the arms manufacturers like Elbit that produce the technology the Israel Defense Forces uses in its wars.

At different scales, these cultural institutions weave legitimacy for Israeli violence, and some directly provide material support to efforts to smother Palestinian resistance. The owners of media corporations and museums, subject to advertiser and donor pressure, protect this legitimacy by retaliating against culture workers who speak out against the bloodshed that their employers help enable.

One major project that culture workers can undertake is therefore to identify the specific organs that provide ideological cover for Israel’s genocidal violence and then to intervene to stop them from doing so. This might include building supermajority support among staff for an institution to embrace the Palestinian Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, organizing freelance workers into refusing to work for a particular cultural organization, and assembling collective protection for workers who face retaliation—firings, forced resignations, canceled bookings—for taking principled public stances. It will surely mean causing a public crisis for the media juggernauts that pretend to maintain journalistic neutrality and instead consistently obfuscate facts, demonstrate a pro-Israel bias, and amplify the IDF’s misrepresentations of the war.

More on the Israel-Gaza War

Culture workers have a second, related task. The political right in the US is waging a war of position to redefine antisemitism as failure to support the Israeli state without qualification. The evidence of this war of position surrounds us: HR 894, which defines anti-Zionism as antisemitic; the highly coordinated and successful right-wing attack on Penn President Liz Magill; moral panics over the phrases “intifada” (uprising), “from the river to the sea,” and “free Palestine,” which all advocate for justice but are misrepresented as slogans for genocide; moves by the federal government, the DeSantis administration in Florida, and individual universities like Columbia and Rutgers to ban chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine.

Here, too, culture workers are uniquely positioned to oppose this assault on solidarity, free speech, and political organizing. We need to organize inside our cultural organizations, our publications, and our academic departments to push for a different set of claims: that all people between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea deserve a life worth living; that Palestinians deserve to live free from bombardment, settler pogroms, occupation, and apartheid; that adhering to the moral principles of Judaism and the historical lessons of the Shoah means opposing Zionist violence and injustice—indeed, opposing Zionism; that, at minimum universities and magazines should enable rather than repress political expression.

And we’ll have to move fast, because our opposition is moving fast, and because we can, in fact, organize to stop the war, though only if we’re smart enough to figure out what works and dedicate ourselves to that project.