Dean Spade Explains How to Come Together and Raise Hell

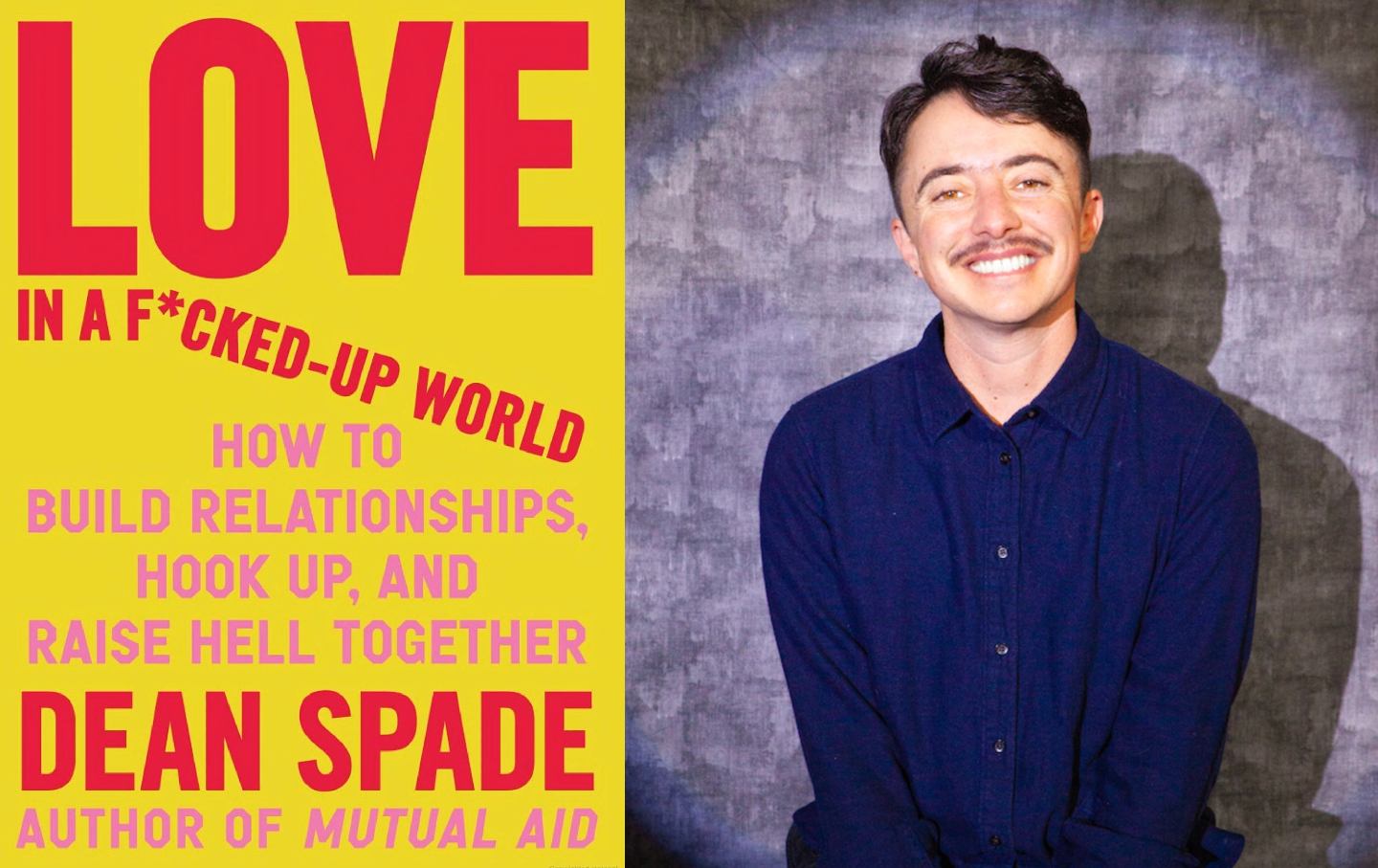

The activist lawyer speaks to Laura Flanders about his radical self-help book, Love in a F*cked Up World.

Dean Spade Explains How to Come Together and Raise Hell

The activist lawyer speaks to Laura Flanders about his radical self-help book, “Love in a F*cked Up World.”

Dean Spade.

(Stephen Anunson)

Climate, healthcare, human rights, work—we are looking at challenges on every front. “And the reality is,” writes lifelong activist Dean Spade, “we’re going to need each other more than ever.” That means that we had better get our interpersonal house in order. And to that end, Spade has written Love in a F*cked Up World: How to Build Relationships, Hook Up, and Raise Hell Together. It’s just out from Algonquin Press. Spade is a lawyer, educator, and author of Mutual Aid: Building Solidarity During This Crisis and Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of the Law. He’s the director of Pinkwashing Exposed: Seattle Fights Back! And in 2002, he founded the Sylvia Rivera Law Project in New York City, a law collective that provides free legal services to trans and gender non-conforming people who are low income and, or people of color. “The famous feminist slogan, ‘The personal is political’ is correct,” writes Spade. “It matters what happens in our intimate lives. It matters for us and for the people and causes we care about.” What’s love got to do with it? A lot.

—Laura Flanders

Laura Flanders: It did occur to me, what is a nice, radical, trans lawyer doing writing a self-help book?

Dean Spade: Over these years I have continued to be part of the struggles that I’ve always been part of—abolition, queer and trans liberation, work around poverty and immigration and war. In all those struggles, another part of the work that I’ve always been doing has been to figure out how to keep collaborations going, to deal with the conflict that inevitably comes up when you do work together that you care about. I’ve been writing this book for about 10 years actually. And work also on myself to figure out how to show up in groups and in relationships related to organizing, without playing out the toxic stuff that we all inherit from our society and from our experiences of difficulty and trauma. This book is about what I see as one of the worst vulnerabilities of our movements. It’s how we treat each other. Can we stick together enough to get things done, to take big risks together, to do difficult things, sometimes with people we don’t know well or don’t have a lot in common with? It’s a pretty big fault line, and I’ve seen a lot of groups and collaborations and projects that we really needed fall apart over the relational piece.

LF: You write in the book that “Before we can even start grappling with what’s within, we have to have the courage to face what we are up against.” That has driven a lot of people to say, “I am going on some kind of vacation,” or “I am going to absent myself for a while because I can’t handle how much we’re up against.”

DS: Part of why it’s so hard to take in is that most of us are taking in all the bad news by ourselves through a screen. That’s not actually the way humans evolved to take in bad news. I think we’re the first set of people on earth who’ve primarily taken in bad news alone. Usually someone would’ve come and told you or you’d already be in a group. I think one of the best things we can do to support our own wellbeing is to be with others. Joining any kind of project in our communities, a creative project, a mutual aid project, something that connects us to others to digest what’s happening and feel like we’re part of anything that is pushing back and supporting care is good. Not just for the world and the people who may get support through your project, but for you. It’s the way to make friends who care about what you care about. It’s the way to break isolation.

LF: The monthly potlucks I initiated at the beginning of 2024 have been a lifesaver for me. For what it’s worth. As to this question of your approach versus others, even in discussing the collectivity of our progress, or our condition, you’re distinguishing yourself from a lot of self-help groups.

DS: I think that a lot of the typical self-help genre is very focused on the individual. It doesn’t contextualize the kinds of suffering that everyone’s going through in a broader feminist, anti-capitalist, anti-racist analysis. If we understand that our individual suffering is a bunch of bigger scripts that we didn’t actually write and that those feelings and strong states aren’t necessarily us, they may actually be stuff that’s implanted, it can be a little bit freeing. I really hope people read the book and realize that the conflict they’re in isn’t unique. I’m hoping that the political context helps people feel, very much in the way that feminism often has offered, a sense of collectivity and resistance in dealing with the interpersonal realm. Our movements are just made of a bunch of relationships. Whether and how we can show up to our movements depends on how we’re doing and what’s happening relationally.

LF: I really appreciate some of the practical tools in the book, and one of them that lingers with me is the “What else is true?” tool? Can you talk about that?

DS: I’m so glad to hear you say that. One thing I’ve noticed a lot is that whenever we’re having a very strong feeling, like, “I’m so angry at the people in this group I’m in,” or “I’m so mad at a person I’m in a dating relationship with,” the world kind of narrows. The tool is designed to help you think through. “I’m so mad at Laura about our disagreement in the group. What else is true?” “Oh, I remember Laura cares a lot about migrant justice like I do. Actually, Laura’s caring for someone ill right now. I may not know why Laura said that, or what she was thinking, because I haven’t asked.” You’re giving context around the way that a conflict or a disappointment can give you tunnel vision.

LF: How do you recognize conflicts that are worth engaging in? I remember Sarah Schulman wrote a book, Conflict Is Not Abuse, which looked into this years ago, and tried to make the point that some conflict we really do need to have.

DS: It’s really useful that I give you feedback about what we disagree on, or that I think we should take a different political position, all of that. Being able to have conflict requires realizing that conflict is normal. We’re the most imprisoning society in the history of the world. We think conflict means someone has to go, and we really are afraid it’s going to be us. So we’re afraid to give feedback, we’re defensive when we receive feedback. I think sometimes what’s happening in organizing is that people have feelings that come from other parts of their lives, from historical experiences in their families, or at school, or in organizing or cultural stories about who’s valuable, not valuable. So I’ve got those feelings going, and I tell you it’s a political difference. How can I know when I’m having strong feelings so that I can be more careful about whether I’m going after you in the meeting about something, but really it’s because I felt left out when you all had drinks and I wasn’t invited.

LF: Now, the idea behind all this work is not so that we can sit in our groups and have engaged and calm meetings, but so that we can get stuff done. You build to the point that we need to be in better shape so that we can take risks. What risks would you be seeing us take right now if we were skilled up in all the ways you describe?

DS: People are going to need to break a lot of rules and laws to survive this period, already we do. We’re going to need to hide people from the police and from immigration enforcement. We are going to need to disrupt the ecocidal industries and war industries that are destroying the planet and killing people. We’re going to need to get each other medicines and procedures that have become illegal under this new administration. People already do a lot of this, but we’re about to need so much more of it because there’s going to be more political oppression, more criminalization of basic survival for people in our communities. We’re going to need to defend each other from eviction. We’re going to need to stand up to cops and stop them from sweeping areas where unhoused people are. We have to turn up a lot to survive and it requires trusting others and learning how to be trustworthy, which I don’t think we necessarily have in place right now.

One thing I’ve been thinking about a lot is that we need to do more underground work. Right now we’re oriented towards being seen doing good and posting on social media and a lot of it is about people’s brands. We’re going to need to do secret, useful, law-breaking work to survive. These are different emotional skills to want to do work without getting public credit. Even that is a distinction from what the social media companies have trained us for.

LF: Are there stories that you see as models or give you hope?

DS: Absolutely. One of the stories that moves me so much I learned from a wonderful book by Vicki Osterweil, called In Defense of Looting. She talks about how in the 1930s there were eviction defenses where people would just walk through the streets and gather people, and they’d go to where someone was being evicted in New York City and stop the eviction because they just had so many people. They defended tens of thousands of people from eviction, one-third of evictions in New York City in the early ’30s, during a period of extreme economic crisis. Right now we don’t have that level of people power, and that’s the level we need because nothing else is going to work. The courts don’t work. There’s no legislation against evictions. We need a lot of people to get really brave. That’s not everybody’s first step in their organizing career. Many people start out like, “I’m going to make food for folks,” “I’m going to do childcare.” All of that is vital and essential. But ideally, a lot of people become brave enough and driven enough towards justice to take big risks together.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation