The Elite College Students Fighting to End Legacy Admissions

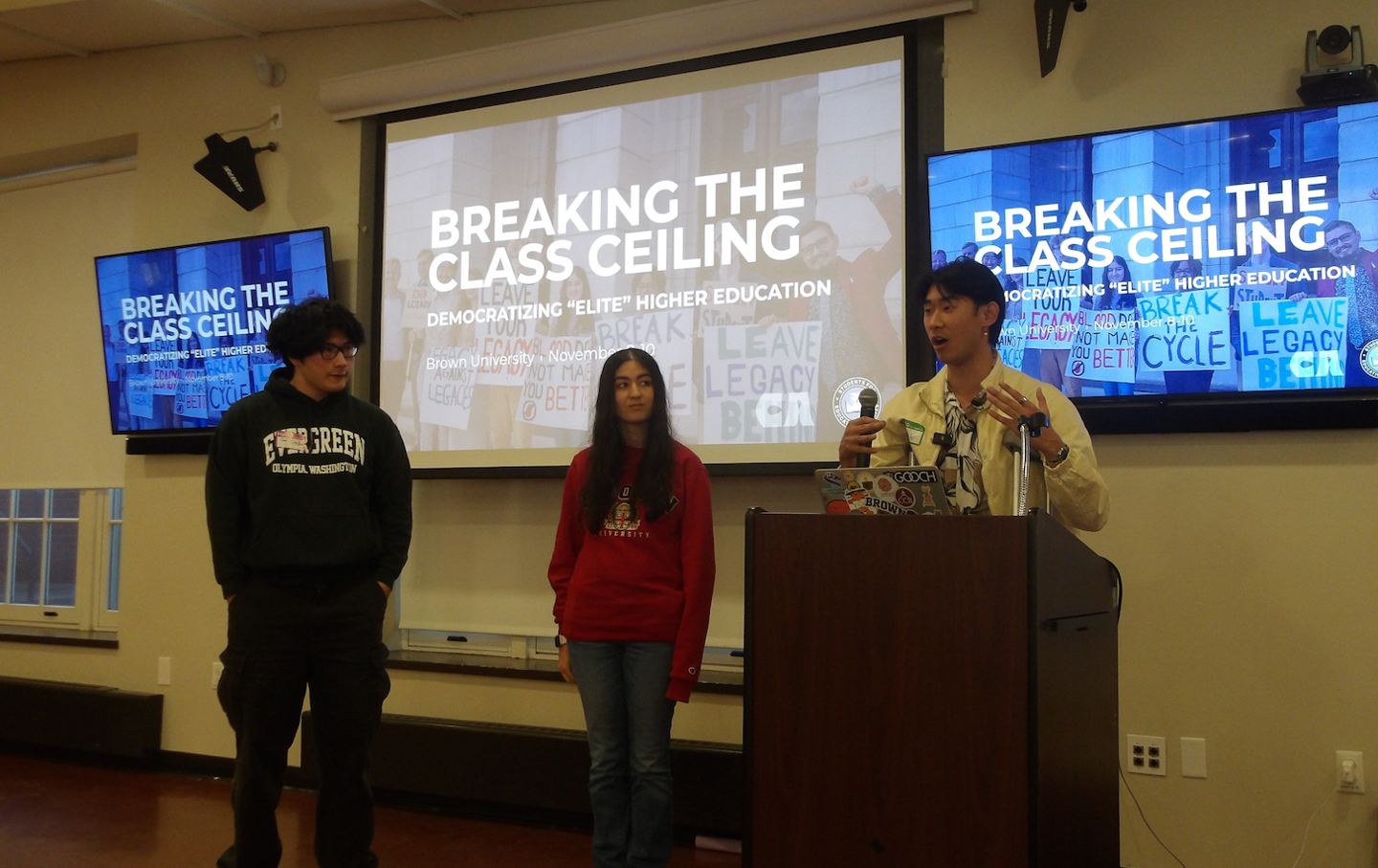

In November, organizers at more than 18 universities met for a conference with Class Action to discuss how to democratize higher education.

A presentation at a conference hosted by Class Action and Brown University Students for Educational Equity.

(Jem Manolios)

After the Supreme Court’s ruling in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard in June 2023, which ended affirmative action, the dream of educational equity might seem further away. Black student enrollment at Brown University, for example, dropped by 40 percent for the class of 2028. At MIT, the newest class is just 5 percent Black, down from an average of 13 percent.

“While I am painfully aware of the social and economic ravages which have befallen my race and all who suffer discrimination,” said Justice Clarence Thomas, “all men are created equal, are equal citizens, and must be treated equally before the law.” But across the United States, students are still fighting for equal treatment in admissions practices. In November, organizers at more than 18 universities met at Brown for a first-ever conference staged by Class Action to discuss how to “democratize elite education” and end legacy admissions.

While affirmative action has been reversed, elite colleges still employ “affirmative action for the rich,” according to Class Action, referring to the Ivy League’s overwhelming preference for legacy admissions—or children of alumni who are “more likely than other applicants to be white and wealthy.” These institutions accept more applicants from the country’s top 1 percent than from the bottom 50 percent, giving a major advantage to the already rich and powerful. “The country’s most heralded institutions like Brown and Stanford and Princeton and Yale are holding on to blatantly nepotistic practices,” said Ryan Cieslikowski, a Stanford alum who founded Class Action in 2023. “Approximately 78% [of legacy admissions] come from the top 10% of household incomes,” reads Class Action’s website. “And according to a 2019 study, at Harvard 7 out of 10 were white.”

For three days, student leaders from Stanford, Harvard, Georgetown, Cornell, Columbia, Princeton, Yale, and more met to “exchange organizing strategy and tactics used in different institutions” and build connections for collaboration. “To see all these students from across the country passionate about creating change and ending legacy admissions, combating career funneling, and just ensuring that we have these equitable spaces,” said Shawn Jimenez, a sophomore at Bowdoin and conference attendee, “it’s really cool.”

In 2018, Brown University students founded the Students for Educational Equity initiative and sponsored a referendum to end legacy admissions. The vote was supported by 81 percent of the student body, but resulted in little response from the administration. Organizers began looking outside of their own campuses for support. “Once we saw that this movement could go from one coast to another, we knew that we had something here,” said Madison Harvey, a junior and copresident of Brown SEE.

Over the last few months, student-led legislation against legacy admissions has gained significant ground. “We recently introduced a bill in the Rhode Island State House, H 8202, to end legacy admissions preferences throughout the state of Rhode Island—although Brown University is one of the only universities that practice it,” said copresident Nick Lee.

In California, Class Action fought for a similar bill earlier this year. “A national organization that opposes legacy admissions and corporate career funneling, Class Action has established a presence at Stanford,” wrote the Stanford Daily in May. “In April, students testified in support of AB 1780 at the State Capitol in Sacramento.” Six months later, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed AB 1780, making it the fifth state to ban legacy admissions.

The change will go into effect in the 2025–26 admissions cycle and impact private institutions like Stanford University and the University of Southern California—not just public universities. “In California, everyone should be able to get ahead through merit, skill, and hard work,” said Newsom. “The California Dream shouldn’t be accessible to just a lucky few, which is why we’re opening the door to higher education wide enough for everyone, fairly.”

But for organizers with Class Action, ending legacy admissions isn’t enough. Students at Johns Hopkins University—where legacy preference is no longer used—explained how the admissions process needs to be followed by intentional programs for first-generation students. “We don’t have the support systems for these students,” says Yvette Shu, a sophomore.

“I was one of those lucky kids who sneaked through the door of an elite school,” said Cieslikowski. “Universities aren’t doing enough to promote socioeconomic diversity, to promote public welfare, and [students] are ready to mobilize and organize against it.”