The Abolitionist Roots of Anti-War Encampments

From Minneapolis to Manhattan, the encampments now spreading across college campuses are built on the same principles as abolitionist spaces like George Floyd Square.

Minneapolis—The police came first. Then the rain. Early last week, an on-campus encampment set up by students at the University of Minnesota was dismantled by law enforcement, and nine people were arrested. Thursday night, students again pitched tents. Rows of police arrived beneath the cover of darkness and told them to disperse. Protesters linked arms and responded with the same chants that filled the streets following the police murder of George Floyd. “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, 10, 11, fuck 12!” (“Twelve” refers to police generally in radical circles.) Then, law enforcement left, arresting no one. Protesters erupted in cheers.

Since April 17, anti-war encampments have spread from Columbia University to hundreds of campuses across the country. In the 200 days since Israel began its latest assault on Gaza, nearly 35,000 people have been killed, including more than 13,000 children. All universities in Gaza have been destroyed. Multiple mass graves have been discovered, including one at Al-Shifa Hospital that contained over 400 bodies. Netanyahu has vowed to invade Rafah next—a Gazan city where over 1 million Palestinians have sought refuge. Still, last week, Biden signed another bill to send Israel an additional $17 billion in weapons.

In occupying their campuses, students are protesting the war, expressing their solidarity with Palestine, and calling on their universities to divest from Israel. The protests find historical precedent in anti-war protests of the 1960s and ’70s, including protests at the University of Minnesota in 1972 that ended with the National Guard patrolling campus. But they also draw inspiration from numerous other attempts to occupy and reclaim space in response to ongoing state violence—in Minneapolis and beyond.

The current anti-war encampments at the University of Minnesota, for instance, are just a short drive from George Floyd Square (GFS), the longest-running political occupation in the state. Since 2020, organizers have held the space, and plan to do so unless 24 demands are met by the city. In the meantime, they are actively building the type of world they’d like to see. In occupying their campuses, students are doing the same.

Though a cease-fire and divestment from Israel are the primary goals of current anti-war encampments, they are not the only goals. Building and maintaining occupied space is a staple of radical movements. Anti-war encampments across the country have set up liberation libraries, free healthcare clinics, and free food networks—all of which can be found at GFS. Some GFS occupiers were also part of the Minnehaha Free State, which emerged in 1998 to prevent the construction of a new highway in Minneapolis—much like the attempt at Standing Rock to prevent the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016.

The Minnehaha Free State lasted just over a year, while Standing Rock lasted just short of one. Both ended with police violently clearing the areas. Similarly, members of the current anti-war movement have been met by an outsize police response: tanks at Columbia, snipers at Ohio State, mounted units at the University of Texas at Austin. Thus far, US police have arrested more than 1,000 protesters. But the protests have spread internationally as well, with police clearing encampments in Berlin and Paris.

Emory University in Atlanta is one of several campuses where the police response to encampments has been particularly aggressive: On Friday, tear gas and rubber bullets were used, 28 people were arrested, and one professor’s head was slammed into concrete. It’s also where the link between movements for police abolition and a Free Palestine are front-and-center, as the Stop Cop City movement is standing alongside anti-war protesters at Emory.

A crossover of the Minnehaha Free State and George Floyd Square, the Stop Cop City movement is working to prevent the construction of a $90 million training facility, where police are to practice quelling protests. Building the facility will also destroy a local forest. Last January, police killed 26-year-old Manuel Esteban Paez Terán (aka Tortuguita), a protester in the forest. They shot Terán 57 times.

“Emory University’s administration is rife with political and financial ties to the Israeli state and the Atlanta Public Safety Training Center, more commonly known as ‘Cop City,’ where the Atlanta Police Department are expected to exchange counterinsurgency and urban warfare tactics with Israeli police as part of the Georgia International Law Enforcement Exchange,” Emory students wrote in a field guide to their occupation.

Police abolitionists have long linked their struggles to the struggle to Free Palestine. See, for instance, Angela Davis’s book Freedom Is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement.

“Some might say that the issues driving the George Floyd mobilizations and the current protests against the war on Gaza are different. But are they?” Davis wrote recently in Hammer and Hope: “Whether or not the Minnesota police ever directly learned combat moves from the IDF, the increased militarization of policing here is directly related to global capitalism, including the economic and military ties between Israel and the U.S.”

But anti-war encampments are also abolitionist in practice: They offer alternative ways of imagining justice, liberation, and freedom. Abolition movements operate under the assumption that current institutions like police and military (working locally and internationally) are systemically violent—especially towards people of color—making them unable to produce peace, justice, or equitable outcomes over time, even with legal reforms.

Abolitionists instead work towards what they call “transformative justice” which, per Mariame Kaba, is characterized by collective solidarity and liberation, radical imagination, and the creation of spaces where everyone can live free from violence, harm, and oppression.

“From Tahrir Square to Zuccotti Park to the quads of each of these universities,” Emory students wrote, “encampments such as ours provide a liminal space, an experiment in collective life between the pressures of racial capitalism and the world we are building.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →On Monday, the University of Minnesota’s last day of classes, rain was still falling—sideways this time. The sky was an ominous gray. A week after the first encampment was erected, students again began to pitch tents. The air had a chill to it, leftover from a winter that wasn’t. Just across campus, cherry blossoms were in bloom.

Ahead of an afternoon rally, the university shut down 12 buildings on campus, including the student union. The wind blew as student chants outside the locked building grew louder: “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free!”

Come nightfall, the police issued a dispersal order, then another. But in the morning, the encampment was still standing. By Tuesday night, the rain had picked up. But students stayed. At Columbia, the epicenter of the movement, hundreds of police in riot gear stormed an occupied building during a comparable downpour and dismantled the accompanying encampment. Protesters were packed onto buses in the darkness, their hands zip-tied behind their backs. A banner hanging from the building paid homage to Tortuguita. Above Terán’s face, it read: “LA LUCHA SIGUE” (“the struggle continues”).

Online, a hashtag was circulating: #ESCALATE4GAZA.

More from The Nation

The People vs. ICE The People vs. ICE

Across the country, neighbors are working together to protect one another from Trump’s immigration crackdowns.

Puerto Rico’s Mothers Against War Turn to Revolutionary Love Puerto Rico’s Mothers Against War Turn to Revolutionary Love

Formed to oppose the Iraq War, Madres Contra La Guerra have now spent decades trying to end Puerto Rico’s role at the center of the US war machine in Latin America.

A Minneapolis Teacher Wants the Whole Country in the Streets A Minneapolis Teacher Wants the Whole Country in the Streets

Dan Troccoli, a public middle school teacher, says everyone should start “emulating” Minneapolis’s resistance to ICE and the Trump regime.

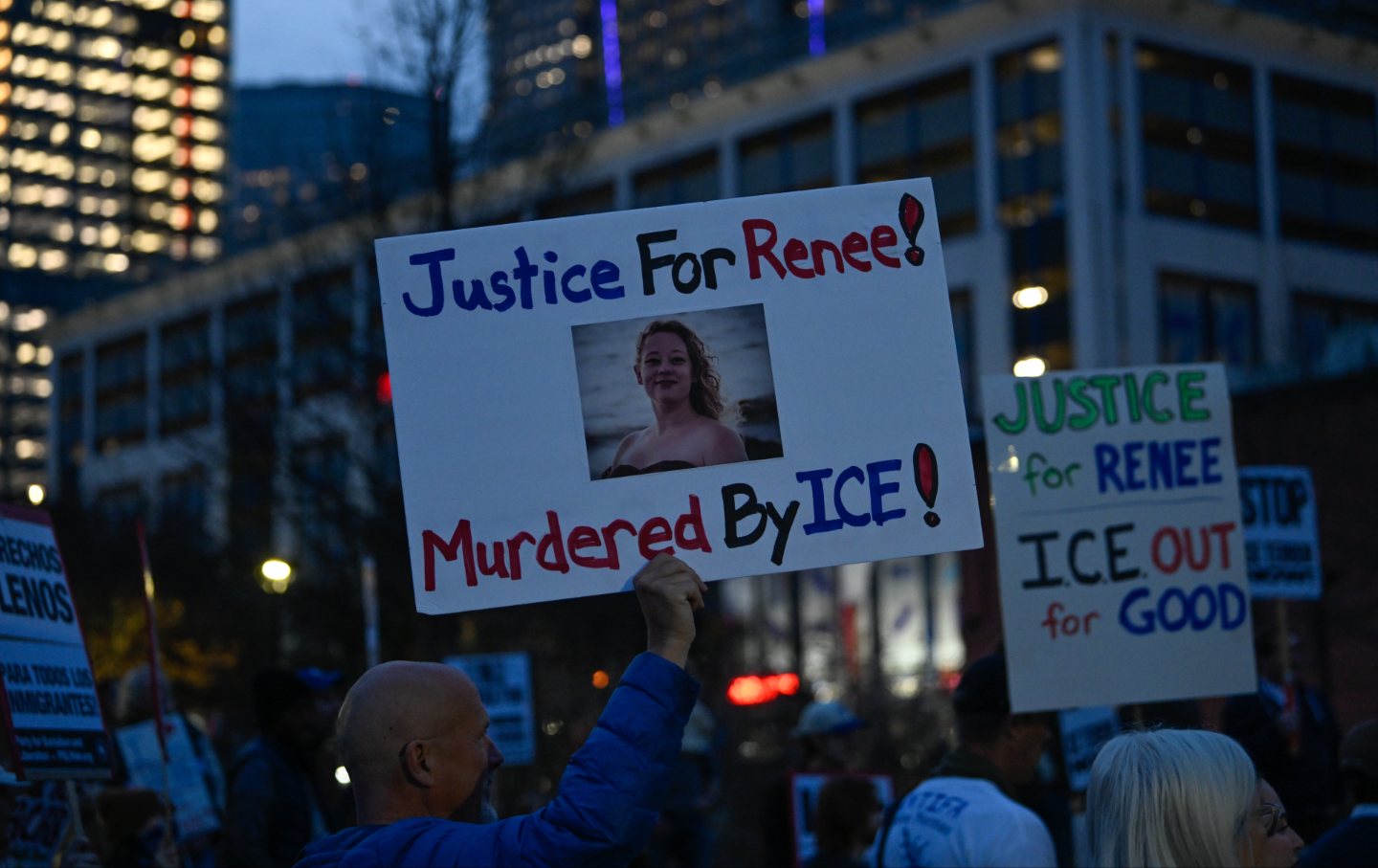

Let’s Make Renee Good the Last Person That ICE Kills Let’s Make Renee Good the Last Person That ICE Kills

We can turn the tide against Trump—but only with mass action and courageous leadership.

Liberals Think Antifa Isn’t Real. But It Is—and It Knows How to Win. Liberals Think Antifa Isn’t Real. But It Is—and It Knows How to Win.

To protect us all from the violence of the Trump administration, we must defend antifa.

Want to Stop ICE? Go After Its Corporate Collaborators. Want to Stop ICE? Go After Its Corporate Collaborators.

ICE can’t function without help from the private sector. So we should force the private sector to stop helping.