Scenes From the Gaza Solidarity Encampments

We asked five student writers to talk about the pro-Palestine protests at their schools, how their administrations have responded, and what the next steps are for organizers.

Pro-Palestinian demonstrators rally after a Gaza Solidarity Encampment was removed by police at UNC-Chapel Hill.

(Travis Long / Getty)On April 30, Columbia University sent in hundreds of NYPD officers to disband the school’s Gaza Solidarity Encampment and remove protesters from occupied Hamilton Hall. The original encampment at Columbia—and the subsequent crackdown—inspired more than 199 similar protests nationwide. To prevent further actions, University President Minouche Shafik has asked the police to stay on campus until two days after graduation.

Not every administration has reacted to the Gaza solidarity protests in the same way. Students at Brown University agreed to willingly disband their encampment after the university pledged to hold a vote in the fall on divestment from companies affiliated with Israel. “On the same day that Columbia University called in the NYPD to arrest dozens of pro-Palestine protesters, the encampment at Brown University ended peacefully,” wrote Owen Dahlkamp.

To better understand what’s happening on campuses nationwide, we asked five student writers to briefly report on the encampments at their schools, how their university administrations have responded, and what the next steps are for the movement.

On the afternoon of Friday, April 26, I entered Harvard Yard through Johnston Gate. A security guard examined my ID. For a moment, I looked back at a small crowd of tourists and press gathered at the gates, blocked by 20 feet of wrought iron.

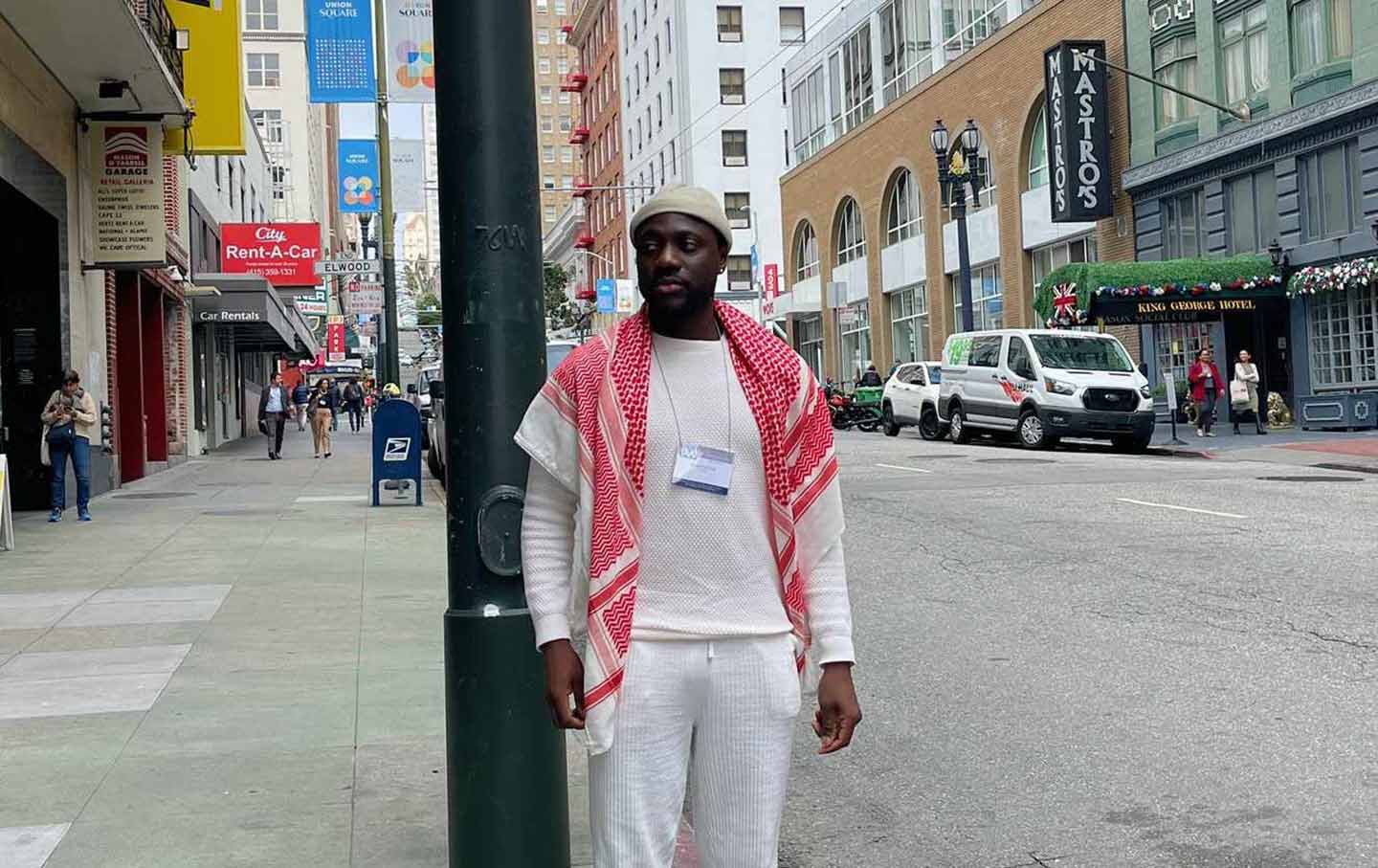

That afternoon, the yard was unusually quiet. Since April 22, it has been closed to the public because of student protests against Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. A large banner that read “LIBERATED ZONE” hung from the oak trees. A canvas strip, perhaps 50 feet long and one yard wide, had been laid on the grass and contained a partial list of Gazans killed by the Israeli military. At least 30 tents around University Hall clustered in front of a statue of John Harvard. Someone had tied a red and white keffiyeh around his neck.

“As you can see, we have a pretty lively camp,” said Violet Barron, a sophomore, pointing out a dining area, supply tent, and event space. There were signs everywhere; their slogans included “DISCLOSE, DIVEST,” “ANTI ZIONISM ≠ ANTI SEMITISM,” and “LET GAZA LIVE.”

“We also have programming to bring the community together,” added Mahmoud Al-Thabata, a first-year student. “Shabbat dinners, open mics, affinity groups doing dance performances.” Indeed, at that moment, Al-Thabata rushed away to join Jum’ah—the Friday midday prayer in Islam—at the event space.

Barron and I talked a little about why she was there. She grew up attending Hebrew school twice a week and had her bat mitzvah in Israel. Though she always had some misgivings about Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, she generally avoided thinking about the issue. “In Hebrew school, I was told that Israel is this dream project that saved our ancestors,” she says. But after October 7—particularly, after Harvard students were attacked for their activism—she rethought her beliefs, and became involved in pro-Palestinian activism herself. “I wanted to be a Jewish voice saying that you can’t just invoke antisemitism in order to justify the suppression of pro-Palestinian speech.”

As we walked, we noticed Rakesh Khurana, dean of Harvard College, watching the encampment from the shade of a nearby dorm with his arms crossed. “He comes by at random hours and just stands there,” Barron said, pointing at Khurana. “Earlier this morning, the administration took pictures of our IDs,” said Barron, “and he came over and watched. We started chanting, ‘Dean Khurana, you can’t hide, you are funding genocide.’ And he just had a deep frown on his face.”

When university administrators closed Harvard Yard, they issued a warning forbidding “structures, including tents and tables” to be erected without prior permission. In an e-mail to students, Dean of Students Thomas Dunne wrote that the encampment has interfered with “the normal activities of Harvard Yard,” a violation of Vietnam War–era rules around student protest. But whether the encampment “interferes with normal activities” is a matter of debate among the student body. The protest is comparatively small compared to the size of Harvard Yard; one could easily walk around the yard and avoid the area entirely.

Later that afternoon, students retreated into their tents to nap or gathered on the steps of University Hall to do homework in the sun. Someone played 1970s R&B from a speaker. Around 3:30 pm, Representative Ayanna Pressley visited the encampment. She stayed for a few minutes, nodding as students talked about their demands. At 6 pm, encampment members, joined by dozens of Jewish Harvard affiliates, gathered for Shabbat dinner.

By midnight, most campers were asleep. It was conspicuously quiet; organizers warned us to keep our voices down. According to the campers who were still awake, things were tense. Earlier that day, protesters had raised Palestinian flags above University Hall, which were promptly taken down by members of the administration. They were increasingly worried about a crackdown. I was repeatedly told there was a chance I would be arrested that night.

Protesters do not expect the administration to treat them charitably. Shraddha Joshi, a senior who has been involved in pro-Palestinian activism for years, says the university “fails to publicly stand up for students who are facing repression for their activism or for their political views.” Joshi was doxxed in the fall—her pictures and personal information were featured on a doxxing truck, and her name was included in the New York Post and the Daily Mail. During this period, she only received nominal support from Harvard administrators.

Over the past week, at least 59 students associated with the encampment have received summonses from the Administrative Board. Still, they plan to stay until the university meets their demands: Disclose the university’s investments in Israeli companies, divest from those companies, and drop all charges against students for their organizing.

“We have eaten, drank, danced, and mourned together—we will face discipline together too,” the organizers wrote in a statement. “We know that we stand on the right side of history, and that the scale of devastation Israel has wrought upon Gaza is a tragedy far worse than any consequences we may receive from Harvard.”

—Rebecca Cadenhead, Harvard University

While students at other universities have erected weeks-long Gaza Solidarity Encampments, attempts at protests at the University of Texas at Austin on April 24 and April 29 have been immediately met by state police, summoned by UT Austin President Jay Hartzell and supported by Texas Governor Greg Abbott.

On Wednesday, April 24, the UT student-run Palestine Solidarity Committee planned an occupation of the campus’s south lawn. Hundreds gathered to participate, demanding that UT divest from companies manufacturing weapons for Israel. But before the protest could begin, police flooded the campus. It wasn’t long before police were backed by more than 100 state troopers. By the day’s end, 57 protesters were violently arrested; police and troopers pulled some demonstrators by the hair, tackled many to the ground, and pressed several of their faces against the concrete.

In the days that followed, students, faculty, and community members gathered on and near the south lawn to host teach-ins and training sessions on civil rights and protest safety. The next Monday, April 29, protesters put that training to action. In a decentralized demonstration—as UT Austin had suspended the Palestine Solidarity Committee just a few days prior—more than 50 protesters erected a small encampment of a few tents and tarps on the south lawn. While state troopers in riot gear, some with assault rifles, along with university and city police, swarmed the lawn, the protesters remained locked arm in arm, using umbrellas and tables as shields.

After surrounding the encampment, troopers and police began ripping tarps out from under protesters’ feet, tearing down tents with large wire cutters, and pulling protesters by whichever limb they could grab first. Later, when protesters attempted to block police from taking those arrested to the county jail—shouting, “Let them go!”—state troopers and police squads deployed stun grenades and pepper spray, burning dozens of unarmed students’ eyes and upping the amount of arrests that day to a total of 79.

On the same day, a Palestinian American student at UT Austin who was arrested during the April 24 protest, spoke at a student-led press conference arranged by the Austin chapter of the Council on American-Islamic Relations. They stressed the importance of not letting the brutality against college students distract from the purpose of the demonstrations. “This doesn’t even compare to what our brothers and sisters in Falasteen, and Gaza specifically, have been experiencing every single day for the past seven months,” the student said at the press conference.

Another UT student, Anne-Marie Jardine, said that on April 24 she spent around 17 hours in the county jail, where she was denied drinking water and medical care for open wounds caused by state troopers during her arrest. Denied period products, Jardine said she was forced to sit in her menstruation-stained clothing and when she went to the hospital upon release, she was told that she had a sprained neck and arm, swollen ribs, and a strained lower back.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Another student protester, who asked to remain anonymous out of safety concerns, said that while they have felt a lot of despair over the past few months, the recent mobilization on campus has given them hope. “When we’re not protecting each other from the brutal police response, we’re serving free food, making art, meeting new people and old friends, and dancing dabke,” they said. “There’s so much creative community building. We’re fighting for Palestinians’ right to live and have freedom, because there’s so much to live for.”

Despite the recent crackdown by law enforcement, organizers at UT show no signs of slowing down. The Palestine Solidarity Committee remains focused on its most recent divestment campaign, launched in February, while continuing to organize on-campus demonstrations planned for the coming weeks, including a celebration in solidarity with Palestine scheduled for May 5, coordinated alongside community groups such as Austin’s chapter of Jewish Voice for Peace and the Austin for Palestine Coalition. “These protests are not about us,” said one protester who was pepper-sprayed on April 29. “They are about Palestine and Palestinian liberation.”

As law enforcement continued to violently arrest dozens on the south lawn during the protest on April 29, one member of the Palestine Solidarity Committee said that she and her peers have no plans of backing down. “We’re still going strong and still standing for Palestine.”

— Aaron Boehmer, The University of Texas at Austin

Hundreds of protesters with Students for Justice in Palestine–Madison (SJP) and the Young Democratic Socialists of America began protesting at 9 am on April 29 at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. The Friday prior, they’d been told by UW-Madison administrators in a campus-wide e-mail that encampments are prohibited under state law and that any violations “will have consequences.” By 9:35 am, protesters set up the tents anyway.

Under cover of darkness on April 29, pro-Palestinian students began getting ready to stay the night on the university’s Library Mall. They were quietly ending their first day, having established the “Popular University for Gaza” encampment, following student activists at Columbia and other universities around the country calling for divestment from weapons manufacturers and other companies tied to Israel.

But come May 1, UW-Madison Chancellor Jennifer Mnookin authorized a police intervention. Police officers tore down the encampment and arrested 34 people—both students and professors.

Sami Schalk, a UW-Madison gender and women’s studies professor, has been a regular attendee at the encampment and was among the 34 people arrested on May 1. “I’ve been released & am at the hospital to be checked out for injuries,” she said on X. “A cop grabbed my dress & ripped it half off my body, injuring my arm.”

Police officers also detained and cited Samer Alatout, a Palestinian professor of sociology who has served as a faculty liaison between protesters and UW-Madison administrators, inflicting a bloody gash on his head. He told The Nation he wasn’t resisting arrest but defending his students. “They come out with riot gear, obviously, to dismantle the students’ voices,” said Alatout. “I think that’s shameful.”

Students began rebuilding the encampment with additional tents after the police left. A UWPD communications director told reporters at a May 1 morning press conference he “wasn’t sure” what the plans would be to remove the remaining tents.

Dahlia Saba, a student protester and SJP member, criticized UW-Madison and Mnookin’s response to negotiators. “This is a student movement. The fact that the chancellor is refusing to listen to students and their demands shows that she is completely out of touch with the people she was supposed to represent,” said Saba in an interview with The Nation.

Communication with the university has been scattershot. The alderman for Madison’s District 8, MGR Govindarajan, said that he had maintained communication between UWPD, protest organizers, and university administrators throughout Monday. But at 6 pm, he stopped hearing from UW-Madison and UWPD. “The anxiety kept building up. People started getting scared. It was getting darker,” Govindarajan said.

When the alderwoman for District 2, Juliana Bennett, and District 2 Supervisor Heidi Wegleitner tried to speak with the police at 10:45 pm, officers told them to leave, physically pushing them out of the building. In a press release on May 1, Bennett criticized the police response and said that she is still “rattled” from the experience.

As of May 2, protesters remain on Library Mall. They’ve set up additional tents and are prepared to remain in place—despite the threat of additional arrests. “We stay grounded in the struggle because we know we won’t stop until Palestine is free,” an organizer told the crowd on May 2.

Since the arrests, student organizers have met with administrators. The encampment’s media liaison, who identified themself by the pseudonym Jules, told reporters that Mnookin met with student and faculty negotiators on the morning of May 2 and is set to schedule another meeting within the next 24 hours. According to Jules, Mnookin pledged to have no further police action at the encampment until at least after the upcoming meeting.

Saba said those at the encampment have found education, new connections, and community while calling for action from UW-Madison. “This has been over six months of an ongoing genocide against the people of Gaza, following 75 years of injustice against the Palestinian people. And it is shameful that UW-Madison still continues to be complicit in all of this,” said Saba. “That’s why we’re here today. To demand an end to that.”

—Liam Beran, University of Wisconsin, Madison

On April 22, the picket in front of the Gaza Solidarity Encampment at New York University fell silent. Time had run out. Campus security had threatened “consequences” if the plaza weren’t cleared by 4 pm. As faculty members started linking arms to form a human chain protecting their students, some of the protesters started to organize themselves for prayer. A student muezzin broke out in a powerful athan as the NYPD started to line the streets around them.

The consequences wouldn’t come for a few hours still, during which a Passover seder was held, communities brought together, food dropped off, and banners painted. At approximately 8:30 pm, as the Muslim students started Maghrib prayer, hundreds of NYPD officers in riot gear stormed the camp, attacking and assaulting students and faculty. Over 120 arrests were made and at least two protesters were pepper-sprayed. One student was pulled by her hair. Another was violently pushed to the ground.

“Many of these institutions, but especially NYU, no longer function as places of learning but as businesses,” said Etta, one of the encampment organizers. “NYU will do whatever it takes to ensure the business continues to make profit. It knows it must use force to prevent ideas being read about in the abstract from becoming reality. It aims to romanticize the past but refuses to acknowledge the present.”

A day before the Gaza Solidarity Encampment was set up at NYU, a mass grave of over 200 Palestinians was discovered at Nasser Medical Complex in Khan Yunis, in the southern Gaza Strip. In response to months of such violence, students organizing the encampment had four demands: for NYU to fully disclose and divest all of its finances—including its endowment—from weapons manufacturers and companies with an interest in the Israeli occupation; a boycott of all Israeli academic institutions and for NYU to shut down its Tel Aviv campus; for NYU to protect free speech on campus and provide fully amnesty to the students and faculty penalized for their pro-Palestine activism; and for NYU to disclose the extent of its relationship with the NYPD and remove its presence from university property.

On April 26, a little after 5 pm, the students at NYU established another encampment. In the hours that followed, the NYPD gathered around them again, and yet another sweep seemed imminent. The university eventually agreed to back down, as long as the students took down their tents and slept without shelter. In the nights that followed, students slept under the rain, covering their bodies with tarp and foil. They read news from Gaza, organized teach-ins, made art, watched and listened to revolutionary film and music. “The current moment shows that the students are the university—that learning is not one-directional,” said Etta. “Students, faculty, and staff are learning together in a cycle of give and take.”

After constructing the “People’s University” on 181 Mercer Street, the Palestine Solidarity Coalition reported that top administrators at NYU had agreed to start negotiations on encampment demands. Following an evening of talks, the university offered only disclosure and amnesty for students arrested at Gould Plaza, contingent on the encampment’s being cleared out and the students’ partaking in university-sanctioned, regulated, daytime protest.

On April 30, the tents were back up. The students, standing in solidarity with Gaza, refused to have their protest sanctioned or regulated. “The mask of the university has finally fallen,” said Thomas, another encampment organizer. “We will make sure to transform them into universally accessible sites for real learning, not real estate operations beholden to donors and administrators who treat faculty and students as disposable.”

At 6 am on May 3, the administration sent the NYPD to clear the camp once more, without prior notice. Sleeping students were woken up by the police and 14 were arrested. But students at NYU will continue to protest. Immediately after the arrests, organizers put out the call for a 4 pm rally. “We are here for Palestine and until admin meets our demands,” wrote the NYU Palestine Solidarity Coalition. “Long live the Student Intifida!”

—New York University

The University of Florida administration has been unsurprisingly hostile to student protests in solidarity with Palestinians. An encampment in the heart of UF has faced constant surveillance, threats, and intimidation since its inception on April 24.

Despite the harassment, the mood at the UF Liberation Zone is one of peace, learning, and solidarity. Encampment programming includes stargazing, interfaith prayers, teach-ins, marches throughout campus, and a daily rally in support of the UF Divest Coalition’s stated demands, including disclosure and divestment of UF’s endowment from weapons manufacturers, Israeli firms, and other entities complicit in genocide.

Despite the anger and anguish that has fueled our activism against UF, we have built an enduring community space where students and faculty can find relief in an increasingly devastating time. Our coalition is made up of first-generation, low-income, and international students and faculty. UF has taken advantage of this fact by holding access to healthcare, food, employment, and shelter over the heads of its students and staff by threatening suspension.

Despite our best efforts at peaceful protest, university and police retaliation has only increased. On April 29, seven students were arrested and effectively expelled pending a disciplinary hearing. The reason: Offending students were sitting in folding chairs, something recently prohibited by the university. These students refused to leave their chairs in solidarity with disabled students whose chairs were confiscated by state police the night before.

UF’s Division of Student Life has drawn up a strict list of unacceptable behaviors within our encampment, which include, among other things, using pillows, sleeping bags, tents, tables, items like water jugs and drums that produce “amplified sound,” or “unmanned signs.” The enforceability of these policies is doubted by legal observers like the ACLU—but not by police, who have confirmed that their only prerogative is to take orders directly from UF’s General Counsel. They have gone as far as to maintain a police occupation of our encampment throughout the night, monitoring protesters between 8 pm to 8 am to enforce the ban on sleeping.

Florida’s elected officials have hijacked public education, cracking down on any form of student advocacy in opposition to the Israeli government’s illegal ethnic cleansing of Gaza. The coming days will undoubtedly see our movement at UF face its climax, as campus operations come to a close for the year. However, we will not voluntarily concede. The gravity of this international crisis and the contempt in which our university has held our concerns leave us no other choice but to continue disrupting, from the confines of our encampment and beyond.

The act of ending our encampment is in the hands of the University of Florida. It can choose whether to do so through a divestment in genocide, or through a violent crackdown on its own students. I hope it chooses the former.

—Cameron Driggers, University of Florida

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation