Health Workers Have Stepped Up for Gaza. Now We Need a Lasting Movement.

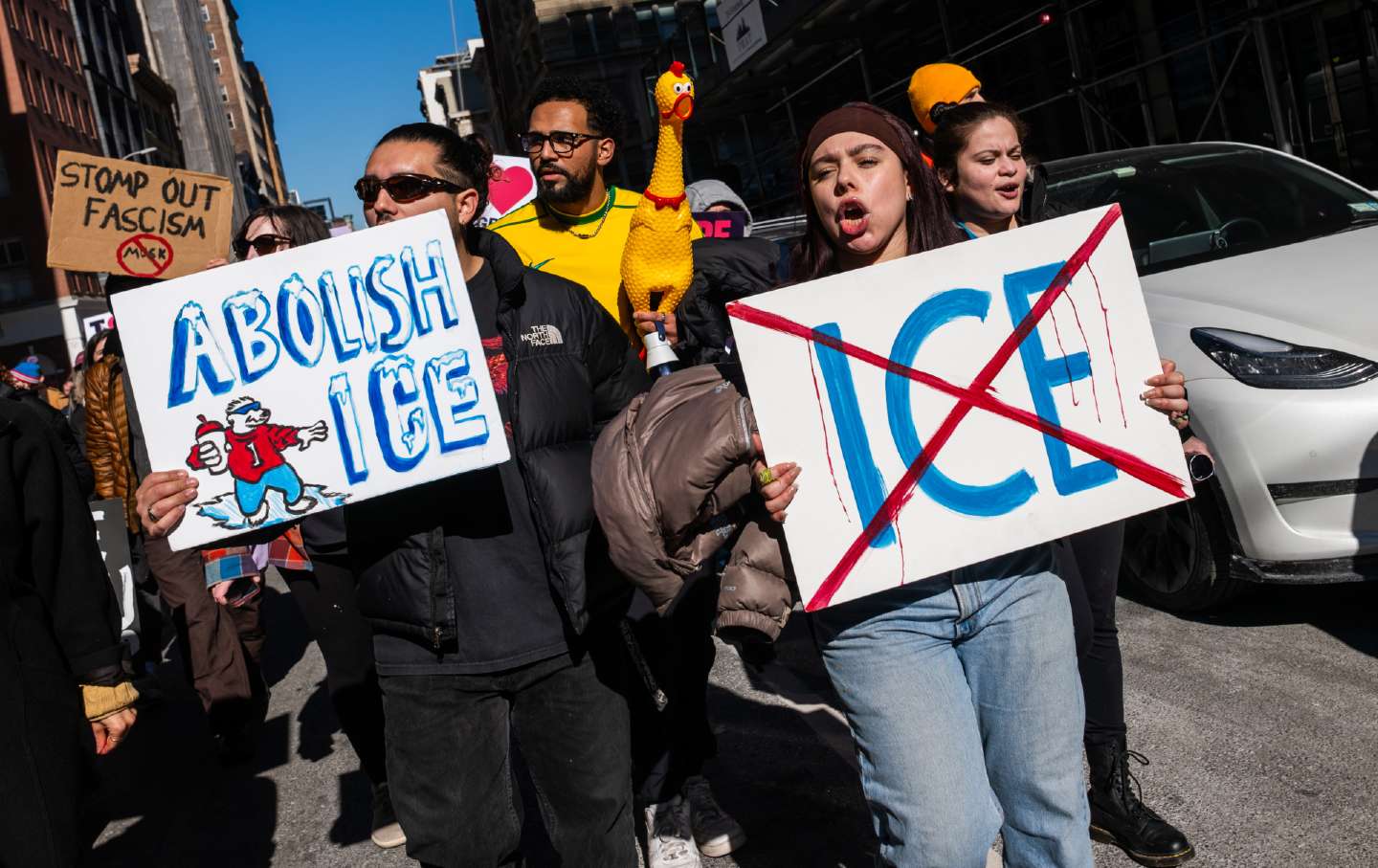

The genocide has galvanized workers across America. It’s time to build on that foundation and organize on a much bigger scale.

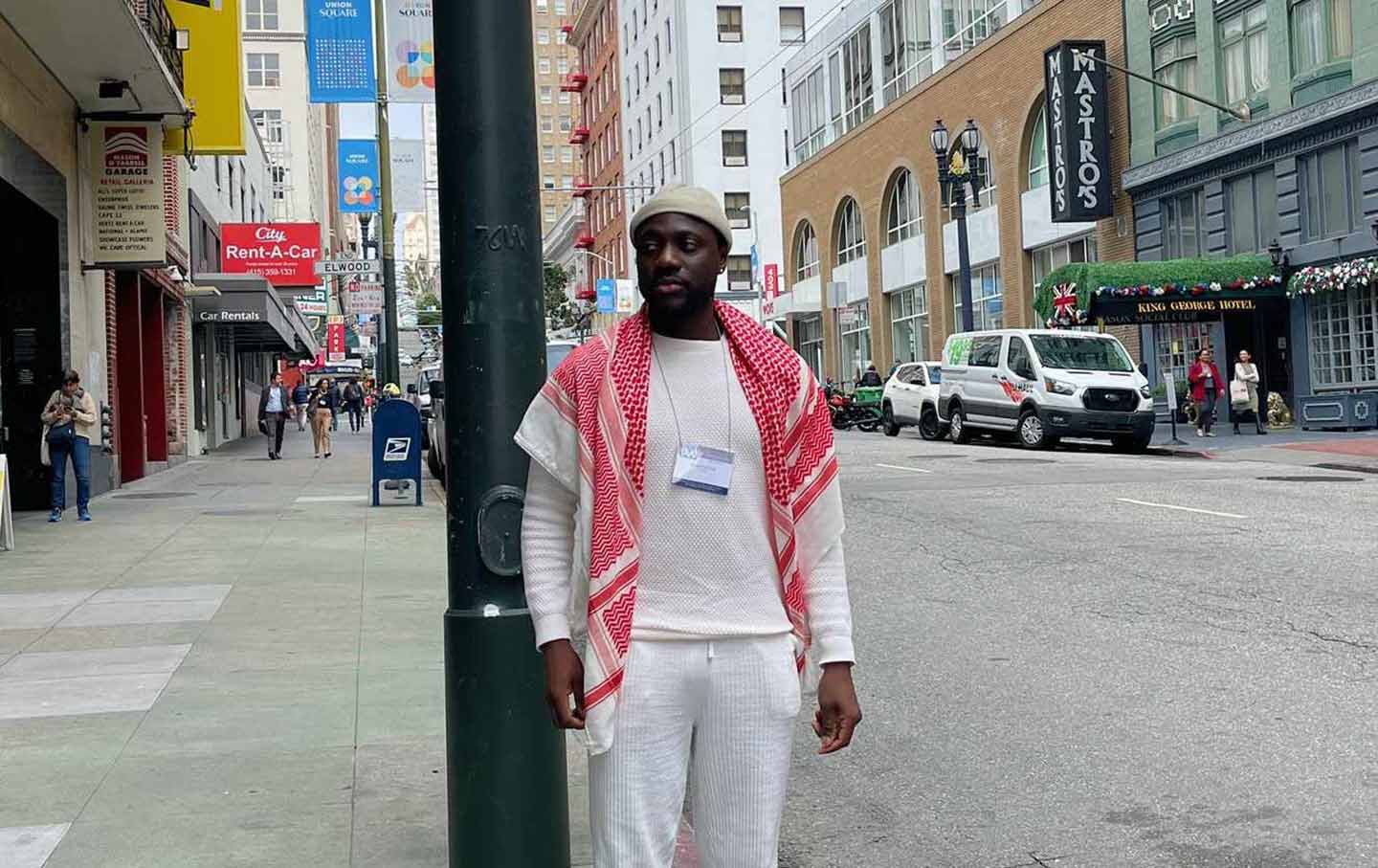

As an Algerian American doctor with an organizing background focused on healthcare, Israel’s destruction of Gaza’s health infrastructure, and the resulting humanitarian catastrophe, have been on my mind, as it has been on the minds of health workers across the country, for months.

The particular urgency with which health workers have been activated around the genocide in Gaza has heightened the contradictions between the kinds of movements and leaders we need, and the organizing reality many of us face. At the same time, the terror of Israeli violence is creating opportunities for unprecedented kinds of working-class internationalist organization.

I am one of countless organizers with Healthcare Workers for Palestine in the US (HCW4P), a decentralized, volunteer grassroots network of health workers in the United States taking action for a cease-fire and a free Palestine. Though I don’t think most health workers mobilizing for Palestine necessarily see themselves as engaged in a class struggle, I do think that the Palestinian solidarity movement is a force that can move health workers into alignment with the broader struggles of the 140 million poor people in the US—if we work to actively build that alignment.

There have been many layers of pain and frustration in this period of mobilization. There is the depravity of the genocide itself. There is also the pain of being an Arab Muslim in a country that has treated our lives and voices as worthless, and of working in a field that is largely silent about and complicit in the genocide. These pains are compounded by the pull to mobilize constantly, often with limited or no connection to organizations grounded in base-building or long-term strategy.

I have seen and been a part of inspiring actions over the past several months alongside my fellow health workers and in large coalitions, but when people are newly activated in response to a crisis, connecting them to a working-class political home they hadn’t already encountered is difficult. This is especially true in the United States, where poverty is seen as a discrete issue and not the basis for organization. In the absence of such a foundation, we are guided by whatever seems the most urgent thing on any given week, by whatever feels good or garners positive attention, or by our reactions to the misleadership of our elected officials. Some are encouraged by changes we see in what the media or politicians say, but there are too few conversations about permanently organized communities.

However, I have also seen the People’s Clinics and other activities of the Nonviolent Medicaid Army (NVMA) make headway. They have helped connect movements of the poor and dispossessed in the US with those who have been put into motion by the genocide in Gaza. NVMA’s “projects of survival,” built from the legacy of the Black Panther Party and other revolutionary efforts, are a form of public protest that indicts the system while meeting people’s needs, heightening their political consciousness. In addition, NVMA’s free People’s Health Clinics have conducted basic health screenings, helped people sign up for benefits and assisted them in fighting back when they get cut off from those benefits, especially Medicaid.

This can be a fundamentally politicizing experience—why are these services out of reach for so many in the richest country on the planet? These questions help us connect everyday people with campaigns grounded in political education and leadership development. The NVMA groups in Elkhart, Indiana, and in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, have mobilized for a cease-fire, making connections between Gaza and the domestic healthcare crisis while developing new leaders. These practices fill me with hope.

What these organizing efforts show is that the concerns of poor people in the US and the concerns of Palestinians in Gaza are not in competition with each other. On the contrary, they absolutely need each other. There is no Zionist state of Israel without the United States. The same forces that shut off our families’ healthcare and threaten their housing are sending weapons to Israel with our tax dollars.

This connection must be embodied and practiced in organization. The NVMA has been a central means for me to make these links. I met a formerly homeless man in Boston as part of this work. He had no identity-based connection to the oppression of Palestinian people, and I don’t know if he considers himself an “activist.” However, he had no trouble seeing the devastation in Gaza as obviously wrong and something worth speaking against. I visited him while he had a brief hospital stay a few months after meeting him last summer, and when I told him that Gaza was on my mind, he told me he had spontaneously joined a rally for Palestinian liberation recently: “I really don’t know a lot about it, but I believe in freedom of speech and defending people that can’t defend themselves.” This is someone with leadership potential.

I have rarely felt inspired by political work centered around healthcare professionals, but our role can be meaningful if we become more deeply enmeshed with broader movements of the poor and working classes. The plastic and reconstructive surgeon and outspoken humanitarian and thinker Dr. Ghassan Abu Sitta is a great example of this—his service to his people, his unflinching denunciation of the ideology and violence that power Zionism, and his emphasis on the material position of health workers is refreshing. I don’t read his work as a call for doctors to be exceptional, but rather to be useful, and to be unafraid. His perspective has sharpened my own perspective on mobilization, organization, and the Palestinian struggle.

Since the beginning of the period I devoted to helping build a union at Montefiore Medical Center, and even before, I thought a lot about different organizational formations and their connections to the struggles of poor and dispossessed people. Because of deep ties between American unions and the Democratic Party, and because the base of the union that we were trying to build consisted of bourgeois doctor trainees, even the Covid-19 pandemic did not compel doctors to seek out more revolutionary politics for themselves. I had no faith that unions of health workers were revolutionary organizations. I always thought that, once the union existed, contact with movements of poor and dispossessed people in the Bronx—like the people who took over Lincoln Hospital in 1970—could help radicalize health workers. I imagined this realignment as a huge wave. Somehow, we needed to be prepared to swim with the current rather than be bowled over by it.

This was just an image in my mind before, but the historic Palestine liberation movement happening in the United States now is giving me the words for it. Perhaps its current can help align health workers with the movements of the poor in a way that the pandemic did not.

But how can health workers, or anyone for that matter, help create the conditions for this? How can we avoid misdirection, distraction, overwhelm, and disorganization so that the movements we belong to are in a stronger position six months from now?

The first step is to understand that mobilization is not enough. A mobilizing mindset says, “We aren’t really trying to develop leaders. We just want as many people as possible to connect with this and take action.” I’ve heard activists say things like this in the past, and it is playing out as networks of health workers and other newly activated constituencies struggle to respond to our current crises.

When I talk about long-term organization of the poor in the US, I’ve sometimes been met with lukewarm reception from my colleagues who do not belong to base-building organizations, or haven’t been exposed to rigorous practices around participation and membership. This is understandable in a moment of such urgency, but we also need a longer-term vision. For me, that vision must consider all of our material connections to the struggle in Gaza. This goes beyond stopping arms shipments to Israel. That tactic is crucial, but as Dr. Abu Sitta and many others have pointed out, the ideology of Zionism will persist beyond a cease-fire. We can’t mobilize our way around an ideology or around the material conditions which sustain it. The genocide depends on the US war economy, and the US war economy in turn depends on the working class.

This broad view of the Palestinian struggle can help health workers contribute and lead more meaningfully. We must continue to direct attention to the barbaric attacks on humanity at Al-Shifa Hospital, and some of us are needed to help fill in for the hundreds of health workers killed by Israel, relieve our devastated colleagues, and rebuild the health system in Gaza.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →The majority of us, however, including many of us in diaspora communities from the Arab and Muslim world, need to also be a part of a broader struggle. Martin Luther King Jr. famously elevated militarism in our thinking as inseparable from racism and poverty. The strategy he proposed for tackling these evils was to unite the poor. These are the people we identify as the leading social force, those with the most to gain and the least to lose from a fundamental transformation of society.

There is currently a groundswell of people who have never been involved in organizing, who are desperate for organization. Some who do not find meaningful organization might mobilize until they burn out. There are multiple theories about the correct way to respond to avoid this, but my tradition of organizing says we cannot do anything if we are not developing leaders. The demise of the original 1968 Poor People’s Campaign happened in part because it relied too much on King’s singular brilliance. Mobilization alone does not naturally develop new leaders, but there is very little talk about this.

The explicit connection between the war in Vietnam and the war on the poor in the US made the original Poor People’s Campaign threatening to the status quo. We must make the same connections now. My plea is not to stop mobilizing but to also organize. This means finding a political home where membership is defined in some meaningful way, and to look into but also beyond the boundaries of unions and contract negotiations. A political home means that relationships are considered a priority, study is considered a priority, and these are given the care and time that they need. In the words of Willie Baptist: “We’re trying to do something that’s never been done before in a period that has never happened before in human history.” We need to organize in ways most of us never have before to meet this moment.