Saving Paradise: The Fight to End Militarization in Hawai‘i

With 6 percent of its land occupied by military bases, Hawai‘i is our most densely militarized state. But young activists are rejecting recruiting efforts and military influence.

Young people with Hawai‘i Peace and Justice during the Solidarity Peace March for Palestine organized by Citizens for Peace Hawaiʻi in January 2024.

(Mariana Monasi)Pete Doktor was lost. Living in Southern California, with the end of high school approaching, he wanted to be a musician, but had no idea how he would pay for music school. His father, a World War II veteran with a wealth of stories on fighting fascism, told him the military was offering money for college.

Doktor had no intention of joining right away, but decided to take a qualification exam. The recruiters started pressuring him, asking if he was too “scared” to enlist and telling him that experience as an army medic would help him later find work. The idea of being able to find such stability and fulfill his “kūleana”—the Hawaiian word for responsibility—was eventually enough to persuade him.

But when Doktor left three years later and started searching for jobs, employers told him the basic first aid training he received was not nearly enough to find work in medicine. He felt misled. “[The military] has an arsenal of things to use to trap people wherever they’re most vulnerable or desperate,” he said.

Motivated by this dissolution, he instead sought to reconnect with his mother’s side and teach English in Okinawa, once a sovereign kingdom in the Pacific that became a military colony of Japan. His next move was to Hawai‘i, where he would learn demilitarization from the Kānaka Maoli, or Native Hawaiians, and “fight the global military empire.” For over 10 years, he worked to ensure that the most vulnerable of his students did not become prey to military recruiters as he once was.

Hawai‘i is the most densely militarized state in the nation. About 17 percent of the population is military-affiliated, and some 6 percent of the land is occupied by military bases. Its remote geography and limited housing also makes it one of the most overpriced. Monthly expenses in Hawai‘i average $3,070—more than any other state. A person making minimum wage in Hawai‘i would need to work 175 hours per week (a week only has 168 hours) to afford the average rent for a two-bedroom unit, according to a 2012 report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Costs have only skyrocketed since then.

That makes young people in Hawai‘i, especially Native Hawaiians, who face even higher rates of poverty, a prime target for military recruiters. Although they make up around 10 percent of the state’s population, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders represent 39 percent of the homeless population.

The military recruits its soldiers with the promise of economic stability and a rise in social status, taking advantage of increasing economic insecurity. Those who enlist receive an income, housing, free healthcare, various veterans’ benefits, full public school tuition coverage, and a uniform that blurs class divides. But activists in Hawai‘i are trying to protect their land from the military’s influence and prevent kids from believing their pitch.

Laurel Mei-Singh, an expert in militarization and a former assistant professor at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, taught veterans who were often Native Hawaiian and working class. She says there is a “poverty draft,” as the military is a rare institution “where there is pretty wide access to services and programs that enable young people to advance themselves.” One young person she spoke to knew five to eight people who joined the military and lived “solid lives,” but also knew three who died fighting.

Some of those who enlist “don’t make it home, but the ones that do, do very well,” said Mei-Singh. “They are able to live a middle-class, American life, that is defined by the comforts that are connected to it. Young people see it as taking a risk, and those from poor and working-class backgrounds are more likely to take that risk.”

The relationship between the US military and Hawai‘i dates back to the time of the Hawaiian kingdom. In 1842, shortly after Hawai‘i was recognized for its strategic location for military and trade, President John Tyler declared control of the island through “virtual right of conquest.”

Shortly after, a group of sugarcane processing corporations led by white businessmen known as the “Big Five” expanded their farming on the island, gaining political influence and pressuring the monarchy to grant them exclusive rights to Pearl Harbor for military use as a “key to the central Pacific Ocean.”

Despite national protests over the Big Five’s excessive influence and the monarchies’ attempt to regain power, King David Kalākaua was forced to sign the “Bayonet Constitution” at gunpoint, which transferred power to the white, land-owning elite in 1887. Only a few years later, the Big Five would overthrow the last Hawaiian monarch with the help of the US military, with the latter establishing the first military base in 1907.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the military evicted residents on the Waiʻanae coast, a 17-mile stretch of land between the Waiʻanae mountain range and the Pacific Ocean—where 62 percent of the population is Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander—to create the Mākua Valley Military Reservation. Since 1848, the people of Mākua have been displaced more than six times in major land clearances. Today, an estimated one-tenth of Waiʻanae’s residents are homeless and many more live below the poverty line. The valley is home to dozens of sacred cultural sites including temples and burials, but for decades was used for live-fire training that damaged these sites, left unexploded ordnance, started fires, and polluted the water.

After receiving statehood in 1959, Hawai‘i experienced a boom of immigration and rapid housing developments, and by 1970, nearly 80 percent of Hawai‘i’s residents could not afford to live in new units that were being built. In the late 1960s, the landlord Bishop Estate evicted scrap metal workers and farmers to build new developments in the Kalama Valley. Often remembered as the first major land struggle and beginning of the modern Hawaiian Renaissance, Kōkua Hawaiʻi (Protect Hawai‘i) led a large-scale movement to guard the residents of Kalama and their homes before they were eventually bulldozed.

In Hawaiian, the word for wealth is waiwai, water-water. When sugar planters first came to places abundant with water, like Waiʻanae, they built wells to divert the water from the community’s use to their plantations, putting a “wrench into Indigenous society,” says Mei-Singh. The military has continued to sever people from their sacred environmental connections, their sources of sustenance and wealth, and their well-being. In 2021, thousands of people in O‘ahu were poisoned when jet fuel leaked into the drinking water from the Red Hill military fuel storage facility.

Tia Marie Masaniai and ‘Alihilani Katoa are youth organizers at Hawai‘i Peace and Justice, an organization dedicated to ending militarization in Hawai‘i. Both Native Hawaiian, they educate high school and college students on the history of Hawai‘i and environmental racism through their organizing with Aloha ʻĀina (love of the land) clubs and a Youth Liberation Camp.

Today, the US military still holds over 200,000 acres, or about 5.7 percent of the total land area. In O‘ahu, the most densely populated island, it controls around 22 percent. Masaniai says that the military presence is especially aggressive in public schools with large populations of Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, like Waiʻanae High School.

There are 18 available Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (JROTC) programs across high schools in Hawai‘i, and Doktor says the mostly non-white, urban school he taught at, Farrington High School, has the largest one in the state.

Maj. Dan Lessard, a spokesperson for the US Army Cadet Command, which oversees the Army’s Junior ROTC and Senior ROTC programs, explains that JROTC is a “leadership and citizenship program, not a recruiting program,” as the vast majority of JROTC cadets will go on to pursue careers outside of military service. “It is, however, a great way for communities to learn more about their Army, especially in areas of the country with little to no Army presence. We also have a mandate to educate JROTC cadets about national service opportunities, both inside of and outside of the military.” Between 2019 and 2021, 44 percent of the Army’s recruits came from a school that offered a JROTC program.

Senior ROTC, on the other hand, which is based at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and available to students in colleges and universities across the state, can cover the cost of college for students who commit to serving in the military upon graduation.

While Americans were being drafted and recruited to serve in the Vietnam war in the 1960s and ’70s, young people at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa were active in anti-war protests. Students for Democratic Society, one of the groups leading this charge, participated in an occupation of the ROTC building to counter these recruitment efforts on campus.

John Witeck, founder of this local chapter of SDS as a student at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in the late 1960s, was arrested over a dozen times for his activism. He burned his draft card and refused his subsequent induction—what he calls an “amazing crime.”

He could have opted out of the draft as a student, but he realized that was a privilege that many poor and working-class kids didn’t get. “The casualty rate was very high in areas like Waiʻanae and Windward,” said Witeck. “We often did a reading of names, and that part of the anti-draft work is to point out racist and harmful impacts on low income and working class communities.”

It is not through chance that poor kids end up in the military so often, but through a manufactured school to military pipeline. No Child Left Behind, an education law signed by President George W. Bush in 2002, required schools to release the names, addresses, and numbers of all high school students to military recruiters. If schools refuse to give the military access to their students, they face cuts to federal funding.

In his 14 years as a teacher, Doktor caught on to a few of the military’s recruiting tactics. One is “the buddy system,” where recruiters approach children sitting alone and pose as friendly company. Some falsely promise a fast-track to citizenship for immigrants, or sell the ideas of escape, adventure, patriotism, and power, often using Hawaiian cultural symbolism to do so.

Above all, they go for kids who are desperate—for a job, for money, for a purpose. When Doktor’s students expressed interest in enlistment, their reasons varied: a desire for education, employment, and discipline, and a general sense of feeling lost. But he would sit them down and explain its benefits and drawbacks, along with the alternatives.

As one of the state’s leading employers, the military has a strong base of support in Hawai‘i. The Department of Defense employs some 68,000 personnel and accounts for 8.9 percent of the state’s GDP, generating billions of dollars for the Hawaiian economy. When Mei-Singh asked her students if they regretted enlisting, many of them said they didn’t. After all, it was the only way being in such a classroom would be possible.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“It’s a place to get three square meals a day, possibly a trade, and have housing as one grows into adulthood,” said Claire Shimabukuro, a longtime organizer in Hawai‘i who was arrested during the Kalama Valley protests as a teenager. “The trade-off is you become someone you’ve never intended to be, that no human should be.”

Many return from war suffering with PTSD and addiction. These are the things that break apart Native Hawaiian families, says Masaniai. “Once you’re not useful to them in their war machine, they discard you. Waiʻanae has a large population of veteran families…and now they are suffering and unsupported.”

But for Katoa and Masaniai, change is on the horizon. In 2029, 30,000 acres of land used by the US military, including in the Mākua Valley Reservation (where the military has not fired live rounds in the last 20 years), will be going up for lease. HPJ is organizing to have this land returned to the people of Hawai‘i. Their current organizing includes bringing young people to military sites that are fenced off and encouraging them to think of ways the land can be reclaimed and repurposed.

To do this, they explain, people must freely imagine what these lands once were, and what they can be once again. “The land is our actual ancestor. It is who we come from,” says Masaniai. Native Hawaiians, according to Masaniai, see the land as their Kūpuna—grandparent—and would do anything to protect it.

Activists have won before. Kahoʻolawe, an island sacred to Hawaiians, was seized by the US Navy and used for live bomb testing for decades. After a series of protests and legislation, the land was finally returned to the Hawaiians in 1994.

Recently, Doktor gave up teaching for health and family reasons, but he’s still organizing around causes from Red Hill to Palestine. He, too, continues to imagine a different world, one that’s not dependent on the military. “The biggest barrier for recruiters are moms and a good economy,” said Doktor. If kids want to join the military to feed their family, you want to honor that “unless you present them with an alternative.”

The next generation should be able to meet their basic necessities without conditions and without having to potentially “invade someone else’s country, kill someone else’s children,” he added. “I have PTSD on both sides of my family, in my maternal side as civilians of war and in my paternal side from military service. And, frankly, I just want the cycle to stop. I have a daughter,” said Doktor, reflecting for a moment. “This is my kūleana.”

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Anger at Corporate Power Is Everywhere Anger at Corporate Power Is Everywhere

It should guide the Democrats.

Honoring the Progressives Fighting for Our Democracy Honoring the Progressives Fighting for Our Democracy

These activists and artists, pastors, and political leaders know what has always been true: The people have the power.

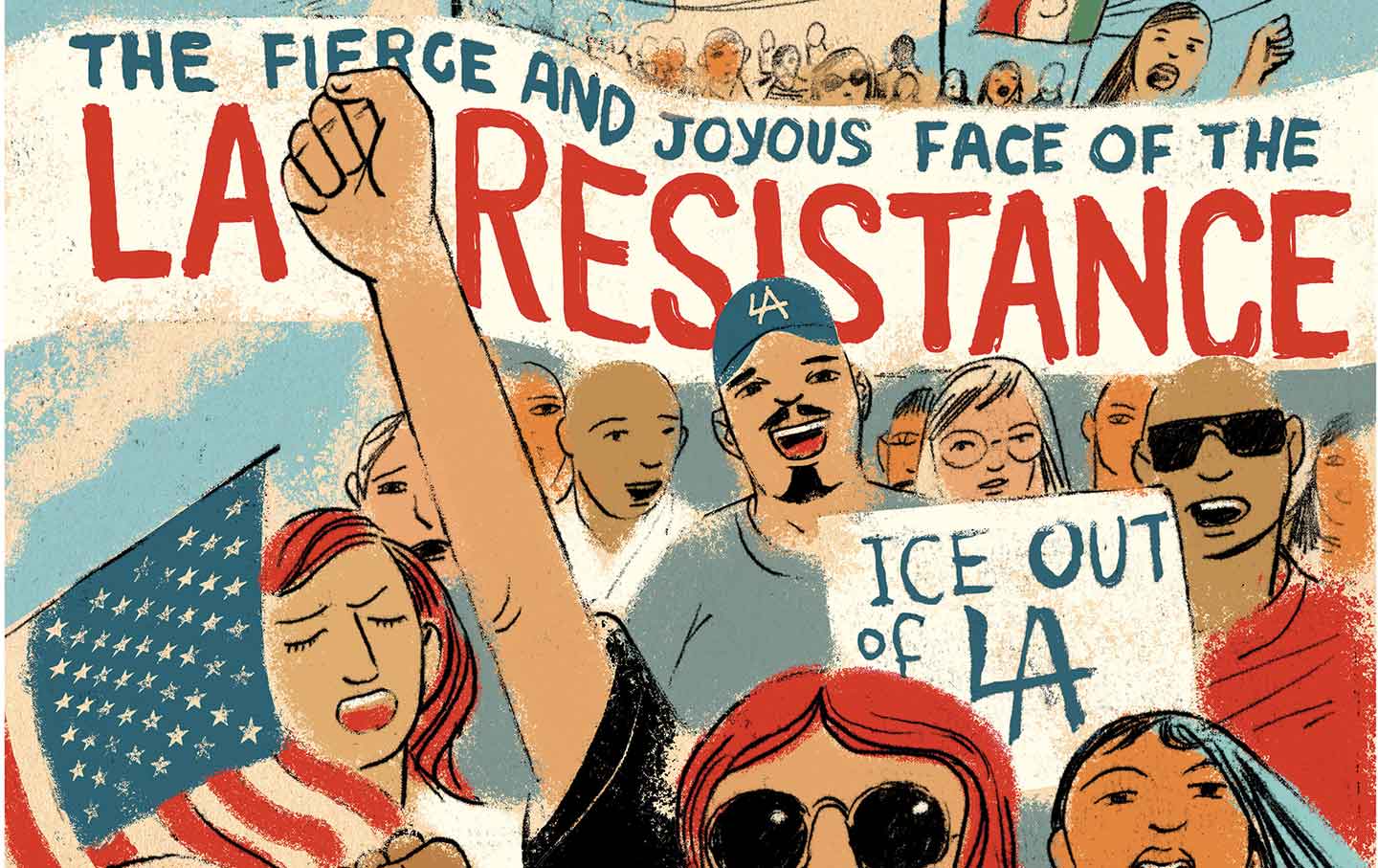

The Fierce and Joyous Face of LA Resistance The Fierce and Joyous Face of LA Resistance

What we can learn from a great American city’s refusal to bend to Trump’s invasion.

San Diego’s Clergy Offer Solace to Immigrants—and a Shield Against ICE San Diego’s Clergy Offer Solace to Immigrants—and a Shield Against ICE

In no other US city has the faith community mobilized at such a large scale to defend immigrants against the federal government.

If Condé Nast Can Illegally Fire Me, No Union Worker Is Safe If Condé Nast Can Illegally Fire Me, No Union Worker Is Safe

The Trump administration is making employers think they can ignore their legal obligations and trample on the rights of workers.

The Counteroffensive Against Operation Midway Blitz The Counteroffensive Against Operation Midway Blitz

How Chicago residents and protesters banded together against the Trump administration's immigration shock troops.