This moment feels different. Something new is in the air.

Of course, everything is always changing. Impermanence is the way of life. Philosophers, theologians, and poets have reminded us for centuries that the only constant is change. As the late, great Nina Simone once put it:

Young becomes old

Mysteries do unfold

’Cause that’s the way of time

Nothing, and no one, remains the same

Still, I think I am not alone in sensing that this year feels different. Something new is in the air.

Some would say it is the stench of death. We can smell it now, almost taste it. Tens of thousands of people have been killed in Gaza in just a few months with our bombs—mass murder funded by our government, aided and abetted by our military, paid for by our tax dollars. We have been told by our government that we are not witnessing genocide.

And yet I, like millions of other people around the world, have watched. I have watched the hearings at the International Court of Justice in The Hague in the case brought by South Africa accusing Israel of committing genocide—hearings that mainstream news outlets refused to air.

But that is not all that I have watched. For more than 150 days, I have watched videos that have traveled around the globe. I have watched as mothers have pulled body parts of their dead children out of rubble, then gathered the pieces—hands, arms, legs—into bags and carried these remains down the street in agony, with grieving relatives wailing and trailing behind them. I have watched as fathers have sprinted to buildings that have just been bombed, arriving in time to learn that their entire family is dead. I have watched as children in hospitals have been told: “Your mother did not survive, and neither did your father, or your sister, or your uncle.” I have seen nurses try to reassure these children, “I am here, little one, I am here for you,” even though the child’s whole family is gone, lost in the rubble. I have watched as children have had their limbs amputated—sawed off—without anesthesia because the hospitals have been destroyed by bombs and there is no medicine, including pain medication, to be found. I have watched as people facing starvation have been shot at by soldiers as they approached vehicles carrying aid.

I have watched and I have watched. All of this is occurring on our watch.

Something different is in the air. But it is not just the mass killing in Gaza, including more than 13,000 children, and the destruction of schools, churches, mosques, hospitals, universities, museums, and basic infrastructure. It is not just the memories of the killings that occurred in Israel on October 7, memories of brutality which many continue to carry along with grief and unshakable fear. More than a thousand Jews were killed on that day, leading to panic and unspeakable pain.

As if all of that were not enough, there is another source of anxiety, fear, and dread that is hanging in the air. This is an election year. And some are saying that if things do not go well, it could be the last election our nation ever has. Democracy hangs in the balance. Donald Trump has said that, if he is elected, he will be a dictator only on the first day of his second term. After that, he suggests, we can trust that he’ll behave himself.

I do not trust Donald Trump.

But it is not just the brutal war or the threats to our fledgling democracy or attacks on voting rights or attacks on the very ideas of diversity and inclusion that have many of us feeling anxious in a different kind of way right now. It is also the climate emergency: 2023 was the hottest year on record since scientists began tracking that data in 1850. Last year’s record beat the next-warmest year, 2016, by a stunning margin. Climate change is accelerating faster than nearly anyone predicted. It is no longer our future; it is our present. And yet the five biggest oil companies raked in record profits in 2022, nearly $200 billion—more than the economic output of most countries.

We wonder why so many young people today are depressed, anxious, and struggling with their mental health. Perhaps it is social media. The attention economy, also driven by a lust for profits, has kept us addicted to our phones—isolated and lonely—endlessly scrolling and comparing ourselves with others, caught in outrage loops and doom spirals.

And yet, as the writer Johann Hari has pointed out, it is normal for any species to become anxious and depressed when its habitat is being destroyed. Even if social media did not exist, why would we expect young people to be anything other than anxious and depressed when they know that, with rapidly accelerating climate change, the conditions for their very survival are being destroyed?

Perhaps technology will save us, some say. The price of green energy has fallen over the last decade and is now competitive with that of fossil fuels; new forms of green technology are being created every day.

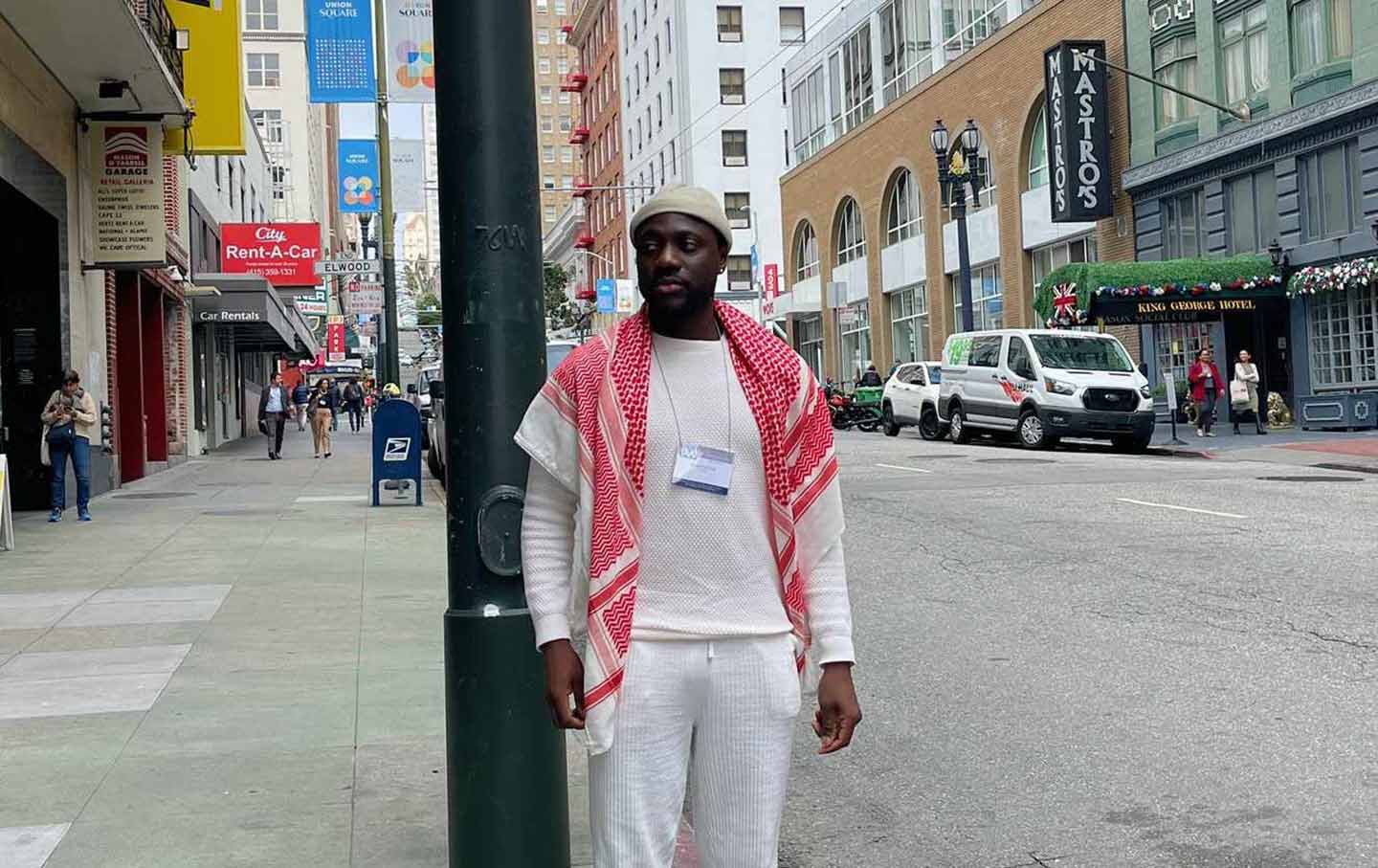

Yet what is also new is the awareness that AI just might destroy humanity. I was at a conference recently where two experts on AI—people who themselves have helped to build and create technologies that have transformed our world—warned that we may unleash a power beyond our control. Many now believe that AI poses a greater threat to our democracy and to our world than the next election. It may even be a greater threat than world war and a more immediate threat than climate change.

Some of you may be wondering what any of this has to do with mass incarceration or police violence—the issues and causes that I have held most dear for much of my life. My answer is that what I’ve just described has everything to do with mass incarceration. I have been talking about the existential crises we face in our nation and our world because we have persisted in treating people—and all creation—as exploitable and disposable, unworthy of our care and concern. We persist in believing that we can solve problems, pursue justice, or achieve peace and security by locking people up, throwing away the key, destroying their lives and families, getting rid of them, declaring wars on them—wars on drugs, wars on crime, and wars on Gaza. Wars are frequently declared on problems, but they are always waged on people.

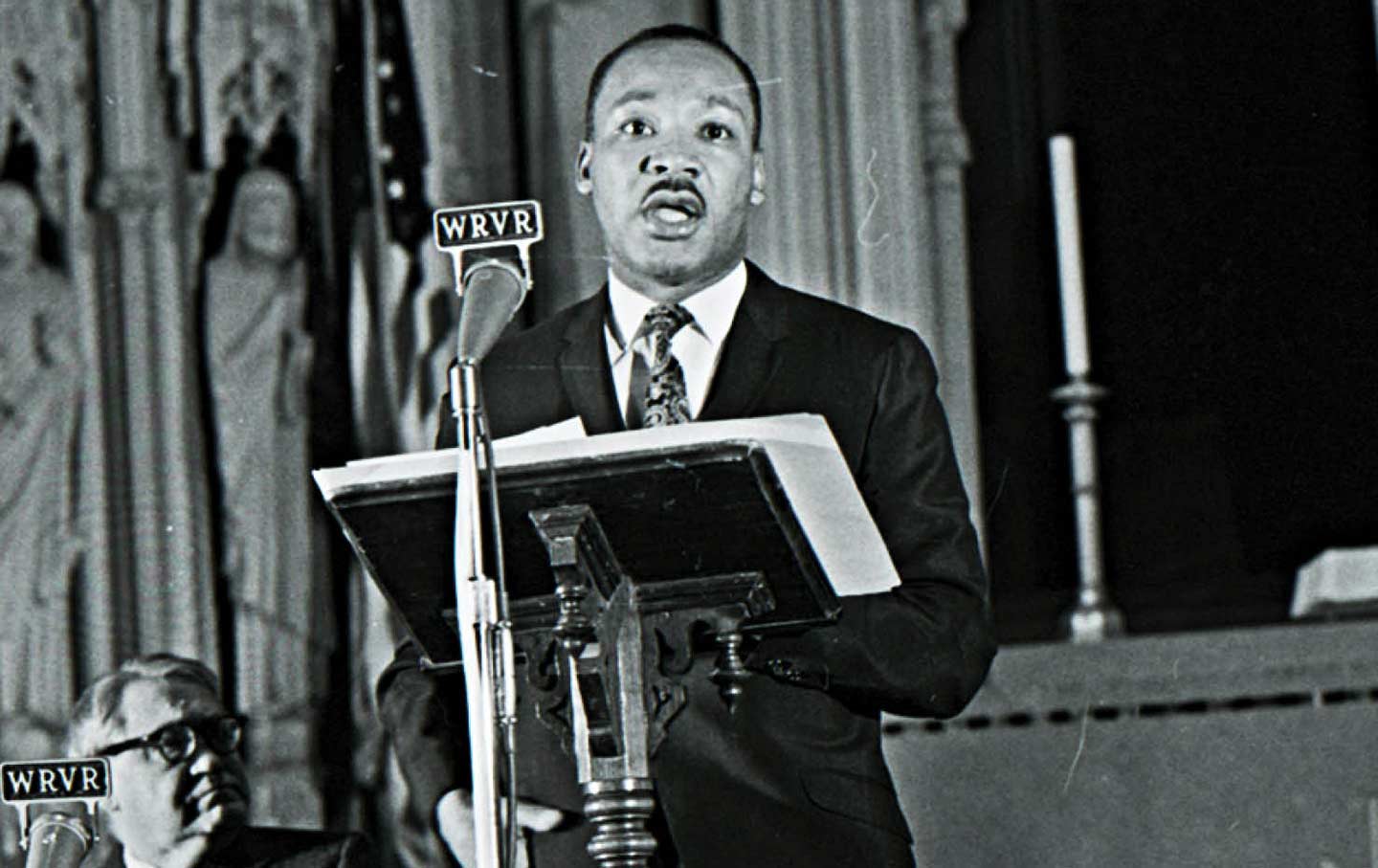

Of all the incredible speeches that Martin Luther King Jr. gave in his lifetime, I think the one that speaks most directly to our times, and that models what is required of us as we face multiple threats to our democracy and our world, is the speech that King gave when he publicly condemned the Vietnam War—and was immediately canceled.

That speech has become a touchstone for me in recent years. Whenever I need a moral compass or my courage begins to falter, I return to the words King spoke at the Riverside Church in New York City on April 4, 1967, one year before his assassination.

King said, “I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice.” He explained that “a time comes when silence is betrayal,” and that time had come in relation to Vietnam.

It is difficult to overstate the political risk that King was taking when he stepped up to the podium at Riverside Church. Our nation had been at war in Vietnam for two years, more than 400,000 American service members were deployed, and roughly 10,000 American troops had been killed. The war had enthusiastic bipartisan support within the political establishment, and those who dared to criticize it were often labeled communists and subjected to vicious forms of retaliation. Many of King’s friends and allies warned him that speaking the truth about the war would jeopardize the fragile gains of the civil rights movement. Little could be achieved, they said, by speaking up for people halfway around the world, and much could be lost. “Why are you joining the voices of dissent?” they asked. “Aren’t you hurting the cause of your people?”

King acknowledged the source of their concerns but said that their questions revealed that they did not really know him, his commitment, or his calling. Indeed, as far as he was concerned, “they do not know the world in which they live.” King acknowledged that it is not easy for people to speak out against their own government, especially during wartime, and that the situation in Vietnam was complex. But he felt morally obligated to speak for the suffering and helpless children of Vietnam. He said:

This I believe to be the privilege and the burden of all of us who deem ourselves bound by allegiances and loyalties which are broader and deeper than nationalism and which go beyond our nation’s self-defined goals and positions. We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation and for those it calls “enemy,” for no document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers.

Far from soft-pedaling his criticism, King described the American government as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world” and urged our nation to get on the right side of the liberation struggles occurring around the globe. He wondered aloud what the Vietnamese people must think of us, a nation that promises democracy, dignity, and equality but delivers bombs instead.

“We herd them off the land of their fathers into concentration camps where minimal social needs are rarely met,” he said. “They know they must move on or be destroyed by our bombs.”

In unflinching terms, King condemned the moral bankruptcy of a nation that does not hesitate to invest in bombs and warfare around the world but can never seem to find the dollars to eradicate poverty at home. He called for a revolution of values. He said:

We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

The moment King ended his speech, he was canceled. More than 160 newspapers railed against him, including The Washington Post and The New York Times. The Post claimed that King’s speech had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, to his country, and to his people.” Many civil rights leaders and organizations criticized him too, including the NAACP. But despite the withering public condemnation, King continued to speak out against the Vietnam War on both moral and economic grounds until his death.

King was right, back then. And he’s still right. He’s just as right today as he was nearly 60 years ago about the corrupting forces of capitalism, militarism, and racism and how they lead inexorably toward war. He was right that if machines and computers and property rights and profits are considered more important than people, we are doomed. He was right, without knowing it, about climate change. About AI. He was right about mass incarceration and mass deportation without ever knowing those terms. He was right about the threats we now face to our democracy and to our world. He was right about the starving, helpless children in Gaza who are being annihilated by bombs paid for by our tax dollars.

Above all, he was right about what is required of us now: to speak and to act with unprecedented courage and with love. To oppose all forms of hate and racism, including antisemitism and Islamophobia. To oppose any policy and any economic system that places profit over people. And to reject militarism and state violence as the answer to our most profound, seemingly intractable conflicts and struggles.

If we are to honor the principles and values for which King sacrificed his life, we must demand a cease-fire in Gaza and an end to the occupation of Palestine. We must speak unpopular truths and organize to save our planet, rebirth our democracy, and embrace human creativity and the natural beauty of our world rather than artificial intelligence and virtual reality.

We must also demand a cease-fire in our communities. But I am not talking simply about ending violence in our streets—violence born of trauma, despair, and desperation. Last year was a record-setting year for police killings in the United States, the highest rate of police killings in more than a decade. Even after all the protests and uprisings, even after all the promises of policy reform and change, the killing and violence perpetrated by those who wear badges has continued unabated.

I think it’s important to keep in mind that every arrest and caging of a human being is an act of violence. This is easy to forget because policing and incarceration have become so pervasive and normalized, but the fact is that locking people in cages at gunpoint is violence. And those who are subjected to state-sponsored violence in this country are overwhelmingly poor people and people of color. We have the largest prison system in the world, a penal system on a scale unlike anything the world has ever seen. Why? Because we chose to respond to racial fears and anxieties with wars. And we chose to respond to poverty and drug addiction and mental health challenges with violence.

If we are going to take King’s life and legacy seriously today—and not just pay him lip service—we must admit to ourselves that we, as a nation, have yet to learn the lessons on nonviolence that he and so many other courageous souls who risked their lives organizing for Black liberation aimed to teach us decades ago.

We haven’t learned yet, and time is running out. The clock is ticking on our democracy, on the climate, and on our hopes for a truly just peace in Gaza and beyond. As King said at Riverside Church, there is such a thing as being too late. He said:

We are now faced with the fact that tomorrow is today. We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now. In this unfolding conundrum of life and history there is such a thing as being too late…. We may cry out desperately for time to pause in her passage, but time is deaf to every plea and rushes on. Over the bleached bones and jumbled residue of numerous civilizations are written the pathetic words: “Too late.”

King’s message was not a hopeless one. On the contrary, he aimed to remind us that we have more creativity and more power and collective genius than we often imagine. He called us to a worldwide fellowship, a radical solidarity, that lifts neighborly concern beyond one’s tribe, race, class, and nation. He called us to embrace an unconditional love for humanity—not just in words but in deeds. Not just when it’s convenient or politically profitable or safe or good for our careers.

Of course, the concept of “love” is often misunderstood and misinterpreted, but it is not some sentimental, weak response. As King explained, “I am speaking of that force which all the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life,” and this force, he said, has now become an absolute necessity for the survival of humankind.

bell hooks echoed this view in her essay “Love as the Practice of Freedom.” She wrote:

Without love, our efforts to liberate ourselves and our world community from oppression and exploitation are doomed. As long as we refuse to address fully the place of love in struggles for liberation, we will not be able to create a culture of conversion where there is a mass turning away from an ethic of domination.

I know many people feel helpless in these times, but there are countless ways in which we can practice freedom by acting with revolutionary love. Even small acts done with love and in the spirit of justice can help to change everything. Consider, for example, what happened in Ferguson, Missouri, when Michael Brown was murdered by the police and his community rose up, took to the streets, and remained there, even as the tanks rolled in. Palestinian activists tweeted messages of hope and solidarity from thousands of miles away, along with instructions for how to survive an occupation, including what to do when the tear gas begins to flow. Those gestures of love and solidarity were not forgotten, leading Black activists years later to travel all the way to Palestine to learn more about the ways in which struggles for racial justice in the United States are inextricably linked to movements for justice and liberation around the world.

A beautiful mural now adorns the Israeli separation wall at the northern end of Bethlehem in the occupied West Bank. It was painted by a Palestinian artist who was inspired by watching the protests in the United States following the killing of George Floyd by a police officer who placed his knee on Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes. The artist painted a giant image of Floyd next to the image of Palestinian youth activist Ahed Tamimi and slain medic Razan al-Najjar. When the artist was asked why he added Floyd to the mural, he said, “I want the people in America who see this mural to know that we in Palestine are standing with them [in their struggle for justice], because we know what it is like to be strangled every day.” Photos of that mural went viral and were featured in news outlets around the world, something the artist never dreamed would occur. A wall that had once symbolized only apartheid now also symbolizes international solidarity in the struggle for freedom.

Obviously, tweets and spray paint cannot change the world by themselves. But they are important reminders that everything that we do or fail to do matters, and that all of us have a role to play.

We can never know if our small acts of love or courage might make a bigger difference than we imagine. The fact that Black activists today are showing up at marches organized by Jewish students, who are raising their voices in solidarity with Palestinians who are suffering occupation and annihilation in Gaza, is due in no small part to thousands of small acts of revolutionary love that have occurred over the course of years, acts that I hope and pray are planting seeds that will eventually bloom into global movements for peace, justice, and liberation for all.

Twenty twenty-four just might be the year that changes everything. But the way that things change is ultimately up to us. It can be a time of world war, genocide, the collapse of democracy, and the loss of hope. Or it can be a time of great awakening—when we break our silences and act with greater courage and greater solidarity, a time when the existential threats that we are facing finally lead us to embrace humanity and perhaps even glimpse the spark of divinity that exists within each one of us, and all creation.

Something new is in the air. And it’s not just dread. In virtually every community, people are coming together in remarkable ways—learning about each other’s histories of struggle, marching together, cocreating with each other, planting seeds of something new together, making another way possible: a way out of no way. People are casting off old ways of seeing the world and being in the world and recognizing that everything depends on us rising to the challenges of our times, speaking unpopular truths, and acting with courage and love and the fierce urgency of now.

In the words of Grace Lee Boggs: “These are the times to grow our souls.” Let this be the moment that we commit ourselves to doing precisely that.

Hold the powerful to account by supporting The Nation

The chaos and cruelty of the Trump administration reaches new lows each week.

Trump’s catastrophic “Liberation Day” has wreaked havoc on the world economy and set up yet another constitutional crisis at home. Plainclothes officers continue to abduct university students off the streets. So-called “enemy aliens” are flown abroad to a mega prison against the orders of the courts. And Signalgate promises to be the first of many incompetence scandals that expose the brutal violence at the core of the American empire.

At a time when elite universities, powerful law firms, and influential media outlets are capitulating to Trump’s intimidation, The Nation is more determined than ever before to hold the powerful to account.

In just the last month, we’ve published reporting on how Trump outsources his mass deportation agenda to other countries, exposed the administration’s appeal to obscure laws to carry out its repressive agenda, and amplified the voices of brave student activists targeted by universities.

We also continue to tell the stories of those who fight back against Trump and Musk, whether on the streets in growing protest movements, in town halls across the country, or in critical state elections—like Wisconsin’s recent state Supreme Court race—that provide a model for resisting Trumpism and prove that Musk can’t buy our democracy.

This is the journalism that matters in 2025. But we can’t do this without you. As a reader-supported publication, we rely on the support of generous donors. Please, help make our essential independent journalism possible with a donation today.

In solidarity,

The Editors

The Nation