On an evening in 1969, a mother carefully prepares dinner in the kitchen. Six siblings drape themselves over schoolwork downstairs, and a grandmother tends to her garden next door. The mother cries out, “¡La cena está lista!” (dinner is ready). In minutes, 18-year-old Jesse Marquez and his five younger siblings are sitting down to eat at the table, when an explosion pushes them all to the floor.

Jesse shakily stands up and notices an incessant ringing in his ears. The smell of burning ash wafts through the kitchen. Jesse’s father pulls his wife up, gathers all six kids with haste, and runs to assist his mother in the yard. He leads everyone to the driveway, where he packs them into the station wagon. As soon as his father starts the ignition, a second explosion rattles them all.

Jesse’s father yells for everyone to exit the vehicle quickly, commanding them to hold hands and run. Their home, pressed together with the many other homes in the South Bay neighborhood of Los Angeles, is clouded by a red-orange sky. As they continue to run, a third explosion interrupts their route, and they all fall to the ground, hitting the unforgiving concrete. When asked later, Jesse did not remember how they managed to escape and arrive at his aunt’s house, but they did. They all had first-, second-, and third-degree burns.

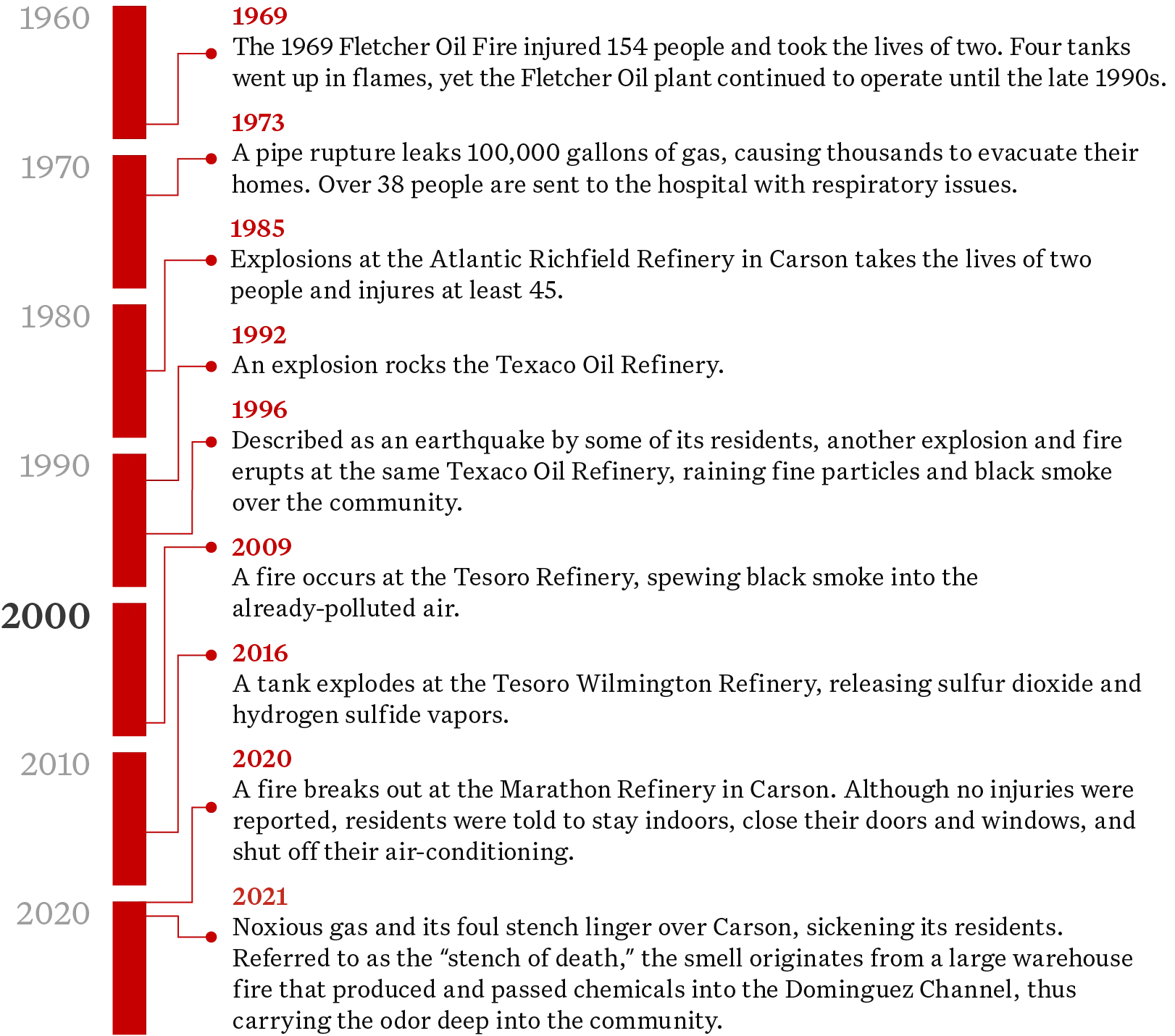

Four tanks of oil in the Fletcher Oil and Refining Co. plant had exploded. The plant was stationed across from Jesse’s family home in Carson, Calif. To live in Carson, Wilmington, or West Long Beach is to live in close proximity to an oil refinery. What happened to Jesse and his family is just one example of the violence oil refineries inflict on the communities they surround.

Thirty-two years after the explosion, Jesse founded the Coalition For A Safe Environment (CFASE) and has served as its executive director since its inception. He works to hold oil refineries and governmental institutions accountable, demanding basic rights for his community of Wilmington.

Big Oil arrived in Wilmington and the Los Angeles area in the early 1900s, spurring economic and population growth in the region. Following the Chevron El Segundo Refinery in 1911, Union Oil opened the first refinery in Wilmington, which began operations in 1919. Over the past century, more refineries and hundreds of their operations have popped up in the region, asserting the oil industry as a powerful employer in the neighborhood.

Carson, West Long Beach, and Wilmington are heavily polluted port communities that carry the oil and shipping economy of the area. As home to oil refineries, smokestacks, major highways, chemical facilities, and the third-largest oilfield in the nation, the residents of these communities are left with an unjust burden: to breathe in the diesel from the cargo containers, trucks, and trains that transport refined oil, among other goods, purchased and consumed by the rest of the country. It is estimated that 37 percent of all American imports and 21.7 percent of all exports are transported through these very ports.

There are about 300,000 residents, the majority of whom are Latino, who live alongside these ports, freeways, warehouses, smokestacks, and refineries. These are the people who carry the dusty air in their bodies.

The Mothers Who Lead the Fight

The day I first called Dulce Altamirano, she answered distractedly. I had caught her at the airport, and she was minutes from catching her flight back to Wilmington from Sacramento. She had been invited to California’s capital for an organizing event to protest oil refineries and the harm inflicted on her community.

In 1997, Dulce moved to Wilmington. She formerly lived in Compton as an 18-year-old trying to make ends meet in a domestic violence shelter for women. She was a single mother looking for the most affordable place to live, and Wilmington was it.

“No sabia de refinerías, de essas industrias. Ni las veía, no prestaba atención en eso entonces.” She did not know of the five refineries that would neighbor her home, darken the sky to a hazy gray, and pollute the air she breathes so much that she now carries a respiratory illness.

In 2015, she began asking questions: What are these buildings? Smokestacks? She thought them to be “fabricas,” factories, at first. It was not until she found herself attending workshops and taking classes at Communities for a Better Environment (about which more later) that she could name what she saw.

“I got heavily involved fighting for a clean environment. The refineries affect the earth, the water, and the air we breathe. We eat the toxic air when we speak,” she says. Dulce, now a mother of five, founded an organization of her own where she and other community members clean the streets and storm drains, ridding them of garbage. She works part-time while her husband lays hardwood floors in apartments and homes.

The volunteers who help Dulce clean are mostly other mothers. These are mothers who have children with asthma, eczema, and Asperger’s syndrome. With air pollution also linked to an increased risk of autism in children, one of Dulce’s children has Asperger’s.

“Motherhood has much to do with this work because to see my son as he is, my grandchildren, my family—this is what most drives me to put in my part, to clean, to fight, to plead for something better against the environmental discrimination in which we are living. Being a mother, a grandmother, this is what drives me with more rage, more force, more.”

Los Angeles is not shy in its activism. The 1968 East Los Angeles Walkouts, the 1992 Rodney King protests, and the 2006 Immigration Rights protests all took place on Los Angeles streets. It is in this history that the Mothers of East Los Angeles, or MELA, was founded in 1984 to protest the state’s plan to build a prison in the neighborhood of Boyle Heights. The neighborhood, inhabited mostly by Mexicans and Mexican Americans, has already felt the development and displacement of the 5, 10, 60, 710, and 101 state highways. These are freeways that car-dependent Angelenos know well, but to Boyle Heights, these are racist monuments that misshaped and severed the neighborhood.

In the 1980s and ’90s, Republican Governor George Deukmejian, known for his pro-law enforcement policies, oversaw the largest expansion of the statewide prison system, which led to a 263 percent increase in the state’s prison population, more than double the national average at the time. Part of the expansion included the building of eight new penitentiaries, one of which was to be located near Boyle Heights. Its location in East Los Angeles was considered ideal for the prison, given its proximity to the courthouse downtown. “It would provide necessary jobs to the surrounding communities, and could house inmates closer to their families,” Deukmejian argued.

Assemblywoman Gloria Molina disagreed, arguing that the history of Boyle Heights is one of displacement. The prison’s proposed location was in close proximity to homes and schools; therefore, its impact would be visceral and harmful to the community. In response, Molina met with Boyle Heights residents. This meeting would later be considered MELA’s first meeting, resulting in a years-long grassroots campaign mobilizing against the prison. During the evenings, Latina mothers met and organized in the basement of a Catholic church, planning their next action to take to the streets alongside hundreds of mothers, children, and their supporters. It took 8 years of protesting and organizing before officials decided not to build the prison in Boyle Heights.

MELA’s fight did not stop with the prison. In 1987, MELA began protesting a waste incinerator planned for its neighboring city of Vernon. Black and Latino neighborhoods in the area would be most affected by the toxins that would be released if the plan succeeded. MELA challenged the project in court and succeeded in putting an end to the company’s efforts. Next, MELA turned its efforts toward a planned oil pipeline.

The mothers of MELA witnessed violence imposed upon their community firsthand: the highways that interrupt their neighborhoods, the prison, the oil pipeline. Activism was not a choice; it was a responsibility to protect their families and their neighbors.

Today, being a Latina mother in Los Angeles looks the same as it did then. It is to love and care for children who are targets of environmental injustice, police brutality, and institutionalized harm. It is to know suffering and faith.

Dulce takes Freddy, her youngest at 13, to the doctor. He was born with a respiratory illness and eczema. At the appointment, she is met with apathy from the attending doctor—a passivity developed from years of appointments with families who are burdened by asthma, eczema, and cancer risk. The doctor hands Dulce a cream that is not strong enough to help with the itching, bleeding, and scratching. Her son and niece scratch so much their “pielcito,” little skin, bleeds. Dulce does not have health insurance, so the appointments and medications must be paid out-of-pocket. She primarily orders medication from Tijuana, telling me it’s stronger and with the right luck, it works. However, sometimes there is no medication that can relieve the itching. The health issues Dulce’s family faces as a result of the refinery pollution are incredibly common for residents of their community.

It is well known that pollution affects the quality of the air we breathe. Experts connected a steep rise in childhood asthma cases to the pollution that haunts the region. Nationwide, asthma rates are especially high in communities of color, and this is the case for the rising rates in the predominantly Latino communities of Wilmington, Carson, and West Long Beach.

Research also suggests that pollution can damage our skin. In 2015, toxicological research from Dankook University in Korea found that toxic chemicals and air quality can trigger eczema. The polluted air damages the skin’s protective layer, resulting in inflammation, dry skin, and itching. Extreme temperatures and dry air worsen the symptoms. The same study links higher rates of eczema to urban areas with high levels of pollution.

Despite the grossly high asthma rates and sicknesses that follow the Latino community, 20 percent of Latinos are uninsured, more than double the uninsured proportion of white people nationwide. Their lack of health insurance discourages those in the community from visiting a doctor for annual checkups and cancer screenings, which are highly recommended for those who live within 30 miles of refineries. Dulce and her family live less than one mile from the Phillips 66 Refinery in Wilmington. The refinery spans 424 acres, with a linked facility located five miles east in Carson. Close proximity to these refineries often results in frequent visits to the emergency room for asthma attacks and other ailments.

In September 2020, Jesse was driven to Kaiser Permanente South Bay Medical Center in Harbor City. He was having an acute asthma attack triggered by high rates of air pollution. The attack took place after Governor Gavin Newsom issued an executive order that did not require ships berthing in California ports to use shore power. Shore power, an alternative to diesel fuel, is used by marine vessels to plug into the local electricity grid for power while the ship is docked. In this process, the ships turn off their auxiliary engines, greatly reducing emissions and the consumption of fuel.

The order, issued on August 17, 2020, was intended to free up the energy supply in California as the state was experiencing extreme heat and raging wildfires. The order halted the antipollution measure that, since 2007, mandated all container, cruise, and refrigerated cargo ships to use shore power to reduce pollution.

Dulce notes that most of the volunteers she works with are mothers whose children suffer from an illness caused by the air they breathe, the air that touches their skin and infiltrates their bodies. Community members meet in her living room and are served coffee from the kitchen, asking one another how to best take care of their neighborhood. This is where it always starts: in the home.

Dulce also works as a volunteer for Communities for a Better Environment (CBE), a nonprofit with a chapter in “the heart of the harbor” Wilmington that fights for environmental justice.

Alicia Rivera is a Wilmington community organizer at CBE. She is often out on the streets, in schools, and in the churches of Wilmington, talking, leafleting, and inviting residents to meetings where they can learn about the refinery issues. Her job is to identify the most pressing concerns of the community.

“In communities of color that are low-income, people notice the refineries, the flaring, and the smoke. They are concerned by how that might be affecting them. They tell you that they think that the asthma or respiratory illnesses or cancer are associated with what they are breathing,” Alicia says.

I ask Alicia who attends the meetings. “Parents are involved. They are all mothers, some with young children,” Alicia says. Alicia, herself, has a daughter with asthma.

It is the activism of women, Latina women, Black women, Asian women, and Indigenous women that gives this community a chance. They are the ones who witness and experience toxic air as a matter of existence in their neighborhoods, so they must act as warriors to take on the fight against pollution. In Wilmington, women are tasked with fighting for their breath.

What’s to Come

When Jesse speaks of Wilmington and the injustices his community confronts, his every word is filled with enthusiasm and feeling. We discuss the latest bills from the California Legislature including Assembly Bill (AB) 617, and its predecessor AB 32, or the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, a program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from all sources throughout the state.

The most recent and major bill, AB 617, signed by Governor Brown in 2017, resulted in the founding of a community-focused program, the Community Air Protection Program. The program’s purpose is to reduce exposure in communities most affected by air pollution. In 2018, the Wilmington, Carson, West Long Beach community was nominated by the district and selected as an AB 617 monitoring community.

“Without key environmental justice organizations, [AB 617] will be a failure because the people that would be involved do not have the experience, knowledge, resources, and connections that we have,” Jesse says.

“Two people got appointed to the AB 617 advisory committee, and we never heard of them. We never saw them anywhere before, doing anything, and they sit at the meetings not saying anything because they don’t know anything, but they work at the petroleum industries,” Jesse says, with frustration and impatience wrapped around each word.

The Green Port Policy was passed in 2005 in response to the diesel emissions that pervade the ports and the adverse health effects that follow. This policy promises San Pedro Bay residents a “cleaner harbor, soil and skies.” I ask Jesse about the green initiatives conducted by the Port of Los Angeles. “Well, ports don’t create initiatives. It’s us, activists, that force them to consider green projects. If I did not start my organization in 2001, we would have a six-lane highway right there. The train track and railroad would be closer to us. Our organization stopped that.” He continues, “United, our community fought it, despite the fact that many organizations did not support me.… YMCA and the Boys and Girls Club did not support me because their multimillion-dollar facilities are funded by the oil refineries.”

This is not uncommon. In fact, it’s the rule. When speaking with Alicia at CBE, she conveyed the same concerns. “Refineries try to co-opt public participation in every way by donating to schools, churches, the Boys and Girls Club, the YMCA. Every local community organization is approached by the refineries for funding. That’s the way they co-opt people from speaking about how they are harmed by the activities of the refineries and the pollution,” says Alicia.

“Catholic Churches have been difficult to work with. They do not allow us to pass out flyers because they say it does not go with the practices of the church, even when we explain that it’s about the well-being of the community.” Despite these challenges, Alicia and CBE volunteers, including members of the church, continue to leaflet on the sidewalks.

“The schools, the libraries, the churches, do not have the resources, otherwise, to continue doing their work without the funding received by the refineries,” Alicia says. In a low-income community and with limited funding from the city, schools and churches look to the refineries as one of the only financial backers for their work. These very same refineries donate money to the reading programs in the library, alongside other community events. In recent years, Dulce organized a local toy drive and received a bulk of toys that were assumed to be from local community members. It was not until after appointments were made with families for toy delivery that Dulce discovered the toys were donated by employees of the Phillips Refinery. “They tricked me,” Dulce says.

Alicia shares similar woes from the community. “Some school principals have told me, ‘Look, if I allow you to pass out flyers, it’s going to affect me. We need that funding to send the kids on field trips, and that funding comes from refineries.’” According to Alicia, the refineries should be providing funding, ideally in the form of a clinic where community members can go to get treated for the various illnesses and diseases directly caused by the refinery. “But what the refineries do is deny that their activities cause any harm to the environment and to the people,” Alicia says.