Thanks to These Activists, in New Mexico Schools There Is Such a Thing as a Free Lunch

Universal free school meals are a popular and effective way to help kids remain engaged in learning and boost local agriculture. Why does it take such a fight to make them policy?

For Alejandro Najera, school lunch is a time to connect with friends: “We talk about our weekends, what we’re gonna do this summer—and gossip. Especially gossip.”

Of course, lunch is also a time for Najera and his friends to fuel their growing brains with tasty food. As the 12-year-old from Albuquerque told The Nation, when he hasn’t eaten properly, “I can’t concentrate. I’m just thinking about what I could eat.”

So when Melanie Maestas, then an administrator at his elementary school, asked him to write a speech promoting a bill that would make fresh, healthy meals free for all New Mexican public school students, Najera agreed. Just 10 years old at the time, he felt nervous: “I was worried that I would mess up and be humiliated.” But he took some deep breaths and delivered the speech in his school lunchroom to fellow students and a few reporters.

“I didn’t expect much of it,” Najera explained. “But a while later they asked me to go to the Roundhouse in Santa Fe to try and persuade legislators.” In front of his state’s Senate Finance Committee, he and Maestas argued that Senate Bill 4 would do much more than universalize school breakfast and lunch, welcoming young people of all economic backgrounds to the table. The bill was also going to minimize food waste by ensuring that students have enough seated lunch time, and mandating that unused school food be donated to combat hunger. Best of all, it would give schools money to source commodities from New Mexican farmers, transition to cooking from scratch rather than relying on processed foods, and craft culturally relevant menus with student and family input.

Najera has always been able to count on free school meals, thanks to the Community Eligibility Provision, a federal program that enables some high-poverty schools to make meals universal. But even when cost isn’t a barrier, it can be tough to get excited about the cheap, mass-produced items that dominate school lunch trays. “If kids have fresh food that actually tastes good,” Najera argues, “then they’ll eat the school lunches instead of just starving.”

Najera spoke so confidently at the Roundhouse that he was invited to join senators on the dais during public comments. Then he and Maestas watched while the committee voted unanimously to advance SB4 to the Senate. A few weeks later, in March, 2023, he sat down at a cafeteria table with Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, and beamed while she signed the Healthy Universal School Meals Act into law.

Universal school meals policies have now been enacted in eight states, with legislative efforts underway in many others. House Republicans have decried these policies as “inefficient,” calling for the USDA to crack down on schools “improperly” allowing kids to eat. But this current push for meal universality is just the latest in a century-long fight to enshrine children’s right to nourishing food. Propelled by a post-pandemic sense of urgency, the chorus of voices calling for Healthy School Meals for All is only getting stronger.

Extensive research has documented the associations between universal school meals (USM) and reduced absences, improved health, and better academic and psychosocial functioning for students. Above all, when meal programs go universal—for example, when the USDA waived its means-testing requirements during the Covid pandemic—student participation shoots up. In New Mexico, about one-quarter of food-insecure children fall outside the USDA’s draconian food assistance threshold.

“I was that kid,” Melanie Maestas told The Nation. “Sometimes I didn’t have the money, and they wouldn’t give me my food. I had a lot of disruptive behavior, and I think that was because I didn’t have access to healthy meals.”

Maestas qualified for reduced-price meals, but that status came with feelings of shame about receiving welfare. There’s evidence that when programs aren’t universal, meal participation rates drop off among certified kids as they age, suggesting that social stigma inhibits adolescents from claiming what has often been framed as cheap food for poor people. That welfare stigma also repels students who can afford to pack a lunch, making it difficult for school nutrition programs to reach robust levels of participation and federal reimbursement.

In 2010, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act introduced Community Eligibility and required schools to serve more fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But USDA meal standards were adjusted without fixing other problems—such as the inadequate staffing and kitchen infrastructure that forces schools to rely on ultra-processed “heat-and-serve” products from Big Food companies like Kraft Heinz and Tyson, or the paperwork burden of means-testing that causes children to spend their lunch periods waiting in long lines. Even though the meals themselves got healthier, students may lack the time or inclination to actually eat them.

“I realized that a lot of kids were throwing their food away in the cafeteria,” Maestas recalled. Fortunately, she was connected to a network of food justice organizers who invited her to help with a campaign to raise the bar for school meals.

Years ago, Maestas’s volunteer work brought her in contact with Los Jardines (The Gardens) Institute, which focuses on environmental justice and land-based learning, and Agri-Cultura Cooperative Network, which supports New Mexican farmers in earning a living through traditional, regenerative growing practices.

Agri-Cultura had cultivated a school garden at the community elementary school Alejandro Najera was attending in 2022–23, helping students to grow their own organic produce. Led by Helga Garza, the network was building a coalition to pass SB4—the product of a decades-long movement. Under its guidance, four different classrooms wrote a total of 150 letters to New Mexican lawmakers, urging them to support the bill. Realizing that a student spokesperson could help move the needle, Maestas chose Najera “because he has a strong voice.”

The legislation promised to invest in Najera’s school community, and others across New Mexico’s South Valley—home to many small farmers and low-income families. Maestas saw the campaign as an opportunity to bring students into the democratic process, “so they can have a voice and be part of decisions.”

It’s critically important for young people to get involved in politics, said the mother of two: “But just make sure you do it with the community, because that’s where it starts. Our elders are the ones that have been in this movement for decades and even generations. We can learn a lot from them.”

One of the elders who guided Maestas into the movement is Los Jardines cofounder Sofia Martinez, who helped to develop the Principles of Environmental Justice back in 1991.

Thirteen years before SB4 supplied funding for schools to support local agriculture, Los Jardines began a farm-to-school program in Martinez’s hometown of Wagon Mound—a remote, rural village where the only way to buy food is by driving forty minutes to Walmart.

When the students first tasted juicy homegrown cantaloupe, they were astonished at how much sweeter it was than the flavorless pre-cut melon from Walmart. When we shop at places like Walmart, Martinez told The Nation, “we’re contributing to corporate farming that abuses workers and ruins the earth’s soil,” robbing it of vital nutrients and destroying essential microbial cultures. The problem is, many of us don’t have a choice.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“The same is true of schools. If we sell our carrots for $4 a pound and the school can get it at SYSCO for $1 a pound—well that gets problematic, right? But the big fortunate thing is that the legislature has provided money so schools can focus on really good, local food.”

The right to eat good food feels personal for Martinez, who grew up on a small farm: “We ate everything we grew. We ate what was considered “poor people food” at the time: purslane and lambsquarters. I call them Chicano and indigenous survival foods because they’re basically weeds. Today, they’re considered Power Foods. The people I knew in my village ate organic until organic became a thing you had to pay for—and then it was out of reach for poor people. We talk about food deserts in the city, but there are food deserts in rural places too. Farming is a really hard business and it doesn’t pay well, so people are choosing to do other things.”

Martinez believes young people deserve to learn about food and gardening—goals shared by school meal crusaders of the Progressive and civil rights eras: “Our whole idea is if everyone can plant a few things, you’re going to start eating better and you’re going to see the difference.”

When the federal government proved that universal school meals are both possible and profoundly impactful by pausing means-testing during COVID, they reinvigorated the “right-to-lunch” movement. State-level USM laws, along with new USDA rules promoting local commodities, are turbocharging farm-to-school initiatives. There’s growing recognition that USDA-backed school nutrition programs—the largest “restaurant” chain in the US—have the awesome potential to fight hunger, collectivize care work, and nurture the ecosystems on which all life depends.

In a climate of intense polarization, USM is a policy with durable popularity across party lines. Recent polling in the battleground state of Pennsylvania, for example, found that 83 percent of voters supported expanding the state’s universal breakfast program to include lunch, while in Republican-leaning Ohio, 87 percent of parents wanted USM as of 2022. Following Minnesota’s USM rollout last year, 60 percent of Republicans approved of the program, even after its price tag exceeded initial projections. Healthy School Meals for All is a powerful coalition-builder, probably because you have to be a supervillain to think it’s a good idea to restrict growing kids’ access to balanced meals.

True to form, the Republican Study Committee has reiterated calls to end Community Eligibility, which states depend on to make universal school meals financially viable.

When I asked Alejandro Najera what he thinks about that, he got straight to the point: “There’s a reason people are asking for free and fresh meals. If you think they’re the problem, you’re wrong. You’re the actual problem in this situation. You’re trying to take away what everyone wants to see—taking away their rights. People want universal school meals. Let them have the meals!”Support independent journalism that exposes oligarchs and profiteers

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

America Needs a New Free Speech Movement America Needs a New Free Speech Movement

Donald Trump is showing us what an unaccountable class of corporate decision-makers looks like—and it looks like a lot of fear, and a terrible loss of freedom.

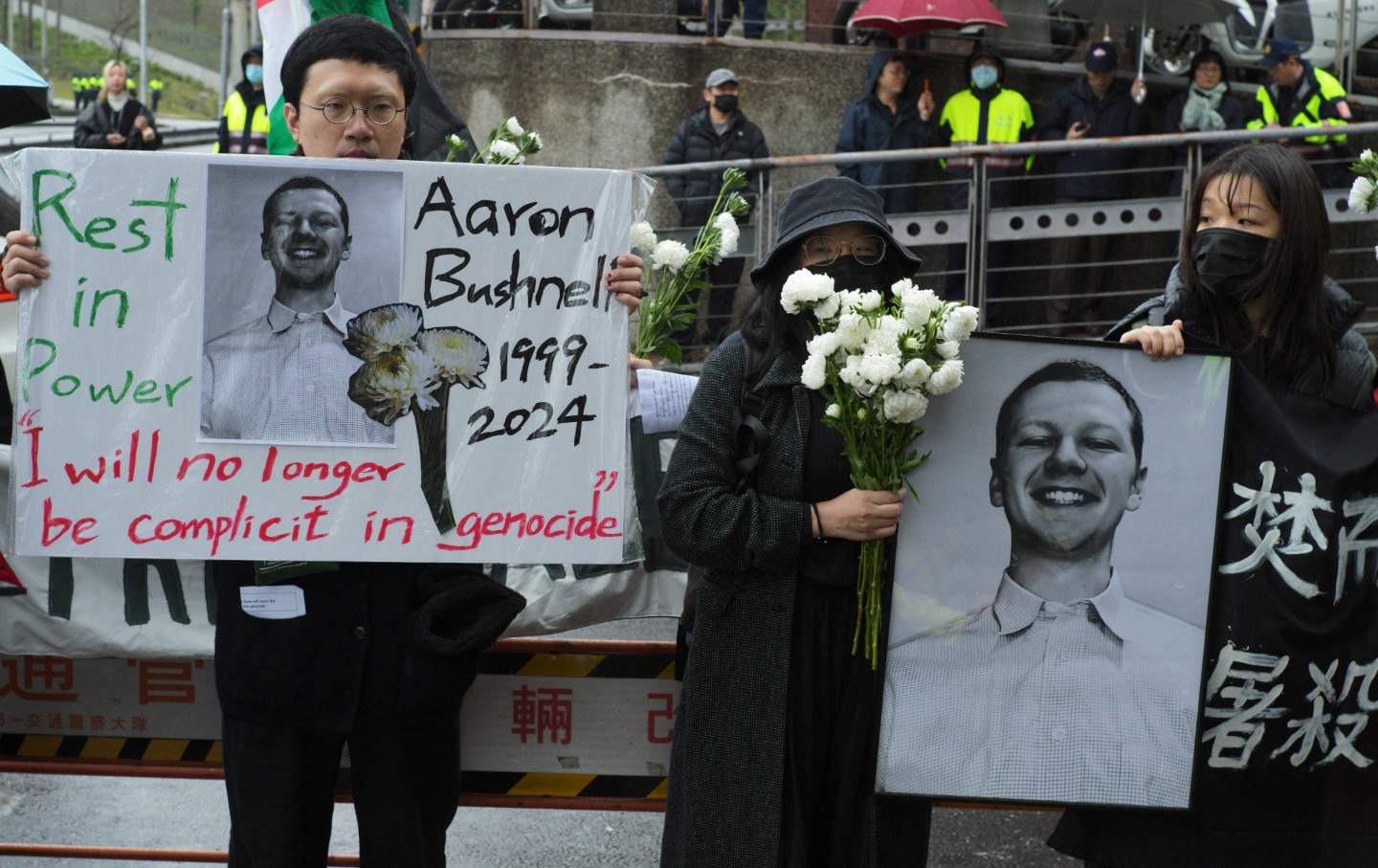

What Aaron Bushnell Is Still Teaching Us What Aaron Bushnell Is Still Teaching Us

His protest was both a rejection of the idea that human life is expendable and an acknowledgment that, for so many, it already has been.

There’s Another St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York—and This One Stands Up to Trump There’s Another St. Patrick’s Day Parade in New York—and This One Stands Up to Trump

The St. Pat’s for All parade started when the more famous Fifth Avenue parade barred queer groups. Twenty-six years later, it welcomes Palestinian solidarity organizations.

We Need to Turn Our Outrage Way Up We Need to Turn Our Outrage Way Up

This is no time to sit idly by. People’s lives are at stake. We have to put our bodies on the line.

Mahmoud Khalil’s Detainment Won’t Stop the Pro-Palestine Student Movement Mahmoud Khalil’s Detainment Won’t Stop the Pro-Palestine Student Movement

The reverberations of Khalil’s arrest are being felt beyond Columbia University’s campus.

Mahmoud Khalil Is the First Activist to Be Disappeared by Trump Mahmoud Khalil Is the First Activist to Be Disappeared by Trump

The detention and attempted deportation of Khalil is a test by Trump to see how far he can go—and a test for us to see how hard we will fight back.