More than a quarter-century ago, Steven Donziger, a young American human rights lawyer, joined the legal effort to force Texaco to clean up the Ecuadoran headwaters of the Amazon rain forest. Between 1972 and 1992, the company dumped toxic waste and spilled billions of gallons of oil-exposed water across 1,700 square miles, an area larger than Rhode Island. In response, a coalition of rural Ecuadorans in the Lago Agrio region sued the US oil giant, and Donziger signed on to help and soon became the lead attorney on the case.

In 2013, after a legal campaign that stretched across two continents, the 30,000 indigenous people and small farmers whom Donziger represented in a class-action lawsuit won a $9.5 billion judgment in Ecuadoran courts against Chevron, which acquired Texaco in 2001. It was one of the largest financial judgments ever against an oil company. It looked like a historic warning to polluters across the Global South. Paul Paz y Miño, the associate director of the environmental group Amazon Watch, described it as “the most important corporate accountability case in history.”

Fast-forward to today, and Donziger is under house arrest in New York City, forced to wear an ankle monitor. The lawyer, now 59, is fighting contempt charges. Meanwhile, his clients in Ecuador have received nothing from Chevron. Without that funding, they have no way to cleanse the poisoned soil or treat what they say is an elevated number of cancer cases.

The mainstream press has largely ignored the legal attacks against Donziger, but Chevron’s counteroffensive could endanger human rights and environmental work around the world. Donziger’s fate, Paz y Miño said, will set a precedent: “Whether it’s Chevron or BP or Shell or any other oil company, if you cannot hold them to account and the lawyer advocating for that case is personally attacked, who else is going to fight those kinds of cases?”

Chevron’s legal onslaught succeeded largely because of a single federal judge in New York named Lewis A. Kaplan. In 2014, Kaplan found Donziger and his Ecuadoran allies guilty of bribery and fraud, which makes it extremely difficult for the plaintiffs to collect their damages in the United States. Then Kaplan asked federal prosecutors in the Southern District of New York to bring criminal contempt charges against Donziger for refusing to turn over his electronic devices, which contain communications with his clients. When the prosecutors declined, Kaplan appointed private attorneys to prosecute Donziger—a nearly unprecedented step by a federal judge.

Kaplan’s hostility toward Donziger has been on ample display in his 21st-floor wood-paneled courtroom in downtown New York for nearly a decade. At times, he has said the pollution case in Ecuador was “not a bona fide litigation” and dismissed the Lago Agrio residents as “so-called plaintiffs.”

Martin Garbus, the legendary human rights lawyer who is part of Donziger’s legal team, is 86 years old and has appeared at hundreds of trials, including in the Deep South during the segregation era. He told me that Kaplan’s treatment of Donziger is the worst he has ever witnessed. “In the courtroom, Kaplan displayed a rage, a fury, that he channeled against Steve,” Garbus said. “He tried to humiliate him. You wouldn’t have to be an expert on the law to recognize it. It was brutal. I’ve never seen a guy eviscerated the way Kaplan tried to eviscerate Steve.”

For his part, Donziger said he hopes the Ecuadorans and their lawyers will hold Chevron accountable. He is a tall man—6 feet, 4 inches—and has been pacing restlessly around his Upper West Side apartment, reading law briefs or talking with his contacts in Ecuador by phone. These days, the coronavirus has driven almost everyone into their homes, but Donziger has already spent months “detained in a small apartment not because we did anything wrong,” he said, “but because we were successful and did a lot of things right. Facing the loss of one’s liberty not because one committed a crime but because of something dark and unaccountable in the system is terrifying. It calls into question most everything I believe about our country and my role in it.”

In an open letter to his supporters last August, Donziger wrote, “I never knew when I started working on this case in 1993 that I would face jail for standing up for the rights of my clients, who have been victimized by what is probably the world’s worst oil pollution…. Quite simply, Judge Kaplan and Chevron are working in lockstep to try and destroy me and my clients.”

The saga began in the 1980s, when Ecuadorans in the rain forest started to protest Texaco’s contamination. The company left Ecuador in 1992, after having dumped crude oil, drilling muds, and an oily, watery mixture known as formation water into unlined waste pits—a procedure that has been outlawed in Texas since 1969. Texaco also released billions of gallons of oil-laced water into the rain forest’s streams and lakes, even though the standard procedure in the United States has long been to inject the potentially toxic compounds safely deep underground.

Five peer-reviewed scientific studies have shown an increased incidence of cancer and other health risks in the area. (Chevron funded its own peer-reviewed study, which claimed to find no such cancer risk.)

About 20 grassroots organizations formed the Amazon Defense Coalition in the mid-1990s, and Donziger, a recent graduate of Harvard Law School, started representing the group in 1993. The Ecuadorans originally sued Texaco in the United States, but after years of delay, a federal judge in New York sent the case to Ecuador in 2001. More than a decade later, Chevron lost. Three levels of Ecuadoran courts up to the Supreme Court ratified the verdict and awarded the plaintiffs $9.5 billion. (Though even if Chevron honored the decision, none of the rain forest residents would receive a check. Instead, the Amazon Defense Coalition would use the money to scour the soil of toxins and build treatment centers for cancer patients.)

Chevron defended itself at every stage of the proceedings in Ecuador, and for years it never challenged the legitimacy of the process. But in 2010 it changed strategies. Chevron launched a countersuit in a New York federal court, alleging that Donziger and his allies had committed bribery and fraud in Ecuador to win the case. The company invoked the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, originally designed to prosecute the Mafia, and in 2011, Kaplan presided over a new trial. Donziger and the Ecuadoran codefendants expected that such serious charges would be tried before a jury, but at the last minute, Chevron dropped its demand for monetary damages. Under RICO law, this meant Donziger and the others lost their right to appear before a jury and Kaplan alone would decide the facts of the case. Charles Nesson, a Harvard law professor, wrote recently in the Harvard Law Record that “Chevron amended its demands to cheat Donziger out of a jury.”

From the beginning of the RICO trial, Kaplan made his pro-business outlook clear. He lauded Chevron as “a company of considerable importance to our economy that employs thousands all over the world, that supplies a group of commodities—gasoline, heating oil, other fuels, and lubricants—on which every one of us depends every single day. I don’t think there is anybody in this courtroom who wants to pull his car into a gas station to fill up and finds that there isn’t any gas there.”

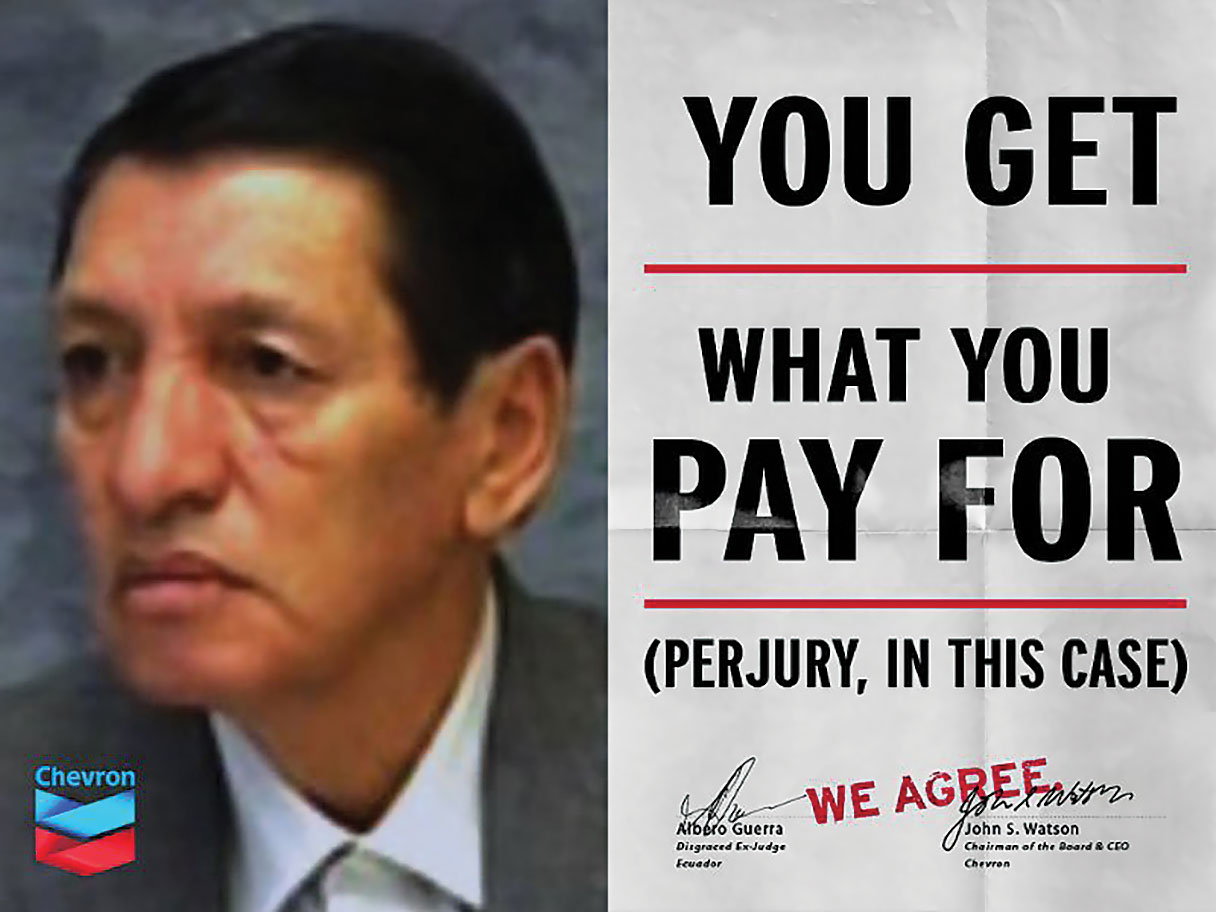

During the case, Chevron claimed that Donziger and his clients had bribed the original trial judge in Ecuador. Chevron’s star witness was Alberto Guerra, a former judge who lost his position on the Ecuadoran bench because of corruption accusations and later, in testimony before an international trade tribunal, admitted to lying about his interactions with Donziger. The oil giant acknowledged paying Guerra and moving him and his family to a secret location in the United States. In all, Donziger estimated that Chevron has spent $2 million on the ex-judge.

Chevron’s lawyers rehearsed Guerra’s testimony with him 53 times and then put him on the stand in front of Kaplan. In his testimony, the disgraced ex-judge asserted that Donziger and an Ecuadoran lawyer, Pablo Fajardo, had offered him a $500,000 bribe and that Donziger and Fajardo had ghostwritten the final judgment against Chevron. Nicolás Zambrano, the judge who had rendered the decision in Ecuador, denied Guerra’s testimony, but Kaplan accepted Guerra’s account, dismissed Zambrano, and found Donziger and his Ecuadoran colleagues guilty in 2014.

Chevron’s legal offensive is an example of a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation, or SLAPP, suit. Over the past few decades, corporations have brought an increasing number of SLAPP suits against environmental and human rights groups. The idea is to spend so much money that your underfunded opponents are forced to give up. The oil giant presumably also has a related aim: to prevent the plaintiffs from ever collecting their cleanup money. Kaplan’s verdict in the RICO case means Chevron can refuse to pay them in the United States. Chevron has long since sold its remaining holdings in Ecuador, so now Donziger and the Amazon Defense Front have to chase the corporation to other countries where it still does business. Chevron’s lawyers are already trying to use the New York RICO judgment to discredit legal efforts against the company in Canada and elsewhere.

Kaplan’s persecution of Donziger did not stop after the RICO verdict. Donziger faces criminal contempt charges because he has so far refused to turn over his personal computer and cell phone to Chevron, as Kaplan ordered him to do last March. Donziger said in a press release that he is defending his clients, because his electronic communications would give Chevron’s lawyers “backdoor access to spy on everything we are planning, thinking, and doing.” He said he wants to wait until the US Court of Appeals hears his defense, after which he will promptly hand over his computer and phone if the higher court confirms Kaplan’s directive.

Sean Comey, Chevron’s senior adviser on corporate issues, litigation, and financial communications, declined to comment for this article. As a result, I was unable to ask him a series of questions, including: Is your company still paying Guerra for his cooperation? How much is it continuing to spend on the legal case? Why do attorneys representing Chevron appear at every hearing against Donziger, even ones that don’t involve the oil company? And what is Chevron’s role, if any, in the multiple legal attacks against Donziger?

Meanwhile, residents in the Amazon rain forest live and work on poisoned land. Donziger cautions that their plight must remain the center of the case. He works closely with Luis Yanza, the elected leader of the Amazon Defense Coalition and a lifelong defender of the environment; in 2008, Yanza won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize, an award for frontline activists. Donziger and Yanza have talked and e-mailed regularly for more than 25 years, and Donziger, who is fluent in Spanish, estimated that he has visited Ecuador 250 times to consult with his clients.

Yanza told me that cancer continues to afflict people in the rain forest. “I visited several of our communities just last weekend, and each one had two or three cases of cancer, including a girl,” he said. And there is no adequate treatment facility in the Lago Agrio area, he added. “The closest cancer treatment center is in Quito, which is seven to 12 hours by bus, depending on where you live.”

He is indignant about the attacks on Donziger. “Steven is totally the opposite of how Chevron portrays him,” Yanza said. “He’s dedicated his life—a great part of his life—to defending people in our poor communities.” Yanza also dismissed the insinuations of critics that Donziger is manipulating the unsophisticated rain forest inhabitants. “This is the mentality of imperialism, saying that we don’t have the capacity to think and to act, to make decisions about our own lives. Steven and others in the United States do provide technical and legal help, but the fundamental decisions are made by us here.”

Donziger’s critics say that he is mainly after his percentage of the judgment, that he’s an ambulance-chasing attorney who found his way to the rain forest. But if that were true, wouldn’t Donziger have given up by now? Surely he would have cut his losses, dusted off his Harvard Law diploma, and found another potential money-making scheme. Instead, he has remained under house arrest for nearly eight months.

Donziger is also fighting to get his law license reinstated. (It was suspended in 2018 without a hearing, based on Kaplan’s findings in the contempt case.) In September and October, he appeared several times at a New York Bar Association hearing in lower Manhattan, before a polite referee named John Horan. The cramped, low-ceilinged hearing room was filled with human rights lawyers and environmentalists who support Donziger—as well as a few conservatively dressed attorneys representing Chevron. A parade of witnesses testified to Donziger’s honesty and integrity, including Rex Weyler, a founder of Greenpeace; Roger Waters of the rock band Pink Floyd; and Simon Taylor, one of the directors of Global Witness, the influential international anti-corruption organization. On February 24, Horan found in Donziger’s favor and recommended that his law license be restored. Horan, a former prosecutor, sharply criticized Chevron’s vendetta, writing, “The extent of [Donziger’s] pursuit by Chevron is so extravagant, and at this point so unnecessary and punitive, [that] while not a factor in my recommendation, [it] is nonetheless background to it.” Horan’s decision must now be reviewed by a New York state court.

On November 25, Donziger appeared before Senior US District Judge Loretta Preska, who will preside over his criminal contempt trial, to ask that his confinement be ended and replaced by an $800,000 bail bond, guaranteed by a number of his supporters. His attorney, Andrew Frisch, reminded the court that Donziger has a family and is not likely to abandon it to flee the United States. What’s more, Frisch pointed out, doing so would mean abandoning his clients in Ecuador. “For 25 years,” he noted, “Mr. Donziger has had his skin, his heart, and his soul in this cause, which is bigger than him.”

In the end, Preska turned down the request. “Mr. Donziger has ties to Ecuador, we know, indeed, to high-ranking government officials,” she said. “We know he has traveled to Ecuador on numerous, numerous occasions…. I find that he remains a flight risk, and accordingly, the request to eliminate monitoring and home confinement is denied.”

Donziger’s trial isn’t scheduled to begin until June 15. He is again challenging his home detention, but he could remain confined to his apartment until then. If this effort fails, he will have spent more than 300 days under house arrest.

Donziger described what it’s like to live under these circumstances. “Sleep is difficult because my ankle bracelet actually blinks and talks,” he said. “A voice reminds me to recharge the battery, which allows the state to monitor my every movement.” The bracelet is “like a giant black claw that clings to your lower leg. It’s designed to be a constant reminder of your banishment, to disorient you psychologically. Of course,” he added, “Chevron and Judge Kaplan want me to be consumed with my survival—rather than helping the indigenous people of Ecuador collect their judgment.”