The UAW’s “Stand Up Strike” Strategy Led to a Huge Win—and Not Just for Autoworkers

The question now is whether that victory provides a launchpad for rebuilding worker power in the auto industry and beyond. Or is just a blip in labor’s steady generational decline?.

There’s a whole truckload of things to celebrate in the new tentative agreements won by the United Auto Workers (UAW) at Ford, Stellantis, and General Motors (GM). The deals were wrested from the Big Three companies after 46 days of expanding strike action—what new UAW President Shawn Fain dubbed the “Stand Up Strike,” in which workers incrementally extended picket lines to more plants, slowing turning the vise tighter on the companies. By the time the last holdout, GM, settled this past weekend, close to 50,000 of the UAW’s 146,000 autoworker members had walked off the job.

Workers won pay raises of 25 percent over the next four and a half years—with bigger raises for many lower-paid workers—plus cost-of-living adjustments, much faster progression to the top of the wage scale, and a host of other economic gains. By mid-2028, top pay for production workers will reach $42.60 an hour, while starting hourly pay will rise from $18.05 today to $28. Crucially, the strikers also won organizing rights at the new Electric Vehicle battery plants coming online.

“The gains are a testament to the UAW’s bold, aggressive strategy under its new leadership, which ramped up the strikes, at first slowly and then faster until the companies caved one by one. It was a master class in worker power,” wrote Dan DiMaggio in Labor Notes. You won’t have to search very far to find similar glowing accolades in left media, and even grudging recognition by the mainstream and business press that the autoworkers have accomplished something pretty remarkable.

But there will be two juries that will render the ultimate verdicts on this historic strike. First up will be the union membership. Over the next few weeks, the autoworkers will pore over the new agreement, whose details have been shared as the bargaining process unfolded—a refreshing and welcome change from past closed-door UAW negotiations. And then they will vote.

Labor observers may be agog to see the big raises that UAW members won, but expect a more sober analysis from the workers themselves. The new top rate of $35.70 an hour for production workers in 2023 is actually $6.40 per hour less—or more than $13,000 less per year—than the same top rate for UAW members in 2007, taking inflation into account. Under the new agreements, a UAW member at the top of the scale can afford to buy a typical home in Detroit or Louisville (barely), but not in Chicago or Kansas City.

Progress? Yes indeed. But the agreements do not restore the wage rates and retirement benefits workers previously earned, nor do they claw back the countless billions that the bosses stole from workers in the intervening generation of concessions, enriching the CEOs and the billionaire shareholders while decimating working-class communities. Auto workers have not forgotten or forgiven this scandalous theft, and neither should we.

The second jury is the future. Three strategic questions remain in play.

First, will the strike be the launchpad for rebuilding worker power in the auto industry, inspiring workers in other industries to rise up as well? Or will it turn out to be a historical anomaly in labor’s steady generational decline?

Today, the UAW represents about 15 percent of the 990,000 US automobile and parts manufacturing workers. That’s down from a peak of 1.5 million UAW members in 1979. Back then, the Big Three controlled 80 percent of the US market, so the UAW contracts drove industry standards. Today, the Big Three market share has fallen by nearly 50 percent as companies like Toyota, Nissan, Volkswagen, Subaru—and now Tesla—have scaled up US manufacturing, all of it nonunion. For years, UAW leaders gave lip service to organizing those plants. In the last decade, the union badly lost efforts to organize at a Nissan plant in Mississippi and a Volkswagen plant in Tennessee; Fain’s predecessor had almost entirely given up on auto organizing.

Earlier this week, Fain—just elected in March following the union’s first genuinely democratic contest for top officers—declared that the 2023 strike “will go down as an inflection point for our union and our movement.” Let’s hope that is the case. Let’s work together to make sure that is the case.

The UAW contract—longer than most at four and a half years—gives the union time to launch a massive organizing drive in the auto manufacturing sector. Rebuilding autoworker power will require herculean efforts by not just the UAW but the entire labor movement. Fain described a vision for the next bargaining round: “When we return to the bargaining table in 2028 it won’t just be with the Big Three, but with the Big Five or Big Six.”

A powerful vision indeed; now the hard work begins. Already the bosses are girding for battle. Toyota wasted no time this week in announcing raises for workers at its five US manufacturing plants. We should expect similar firewalls to go up at all the nonunion companies as they mount their union-busting campaigns of intimidation and division.

A second question to be answered in the coming years is what sort of union will now inhabit the factories of the Big Three. Will members draw from the riveting experiences of the last months and build militant shop floor unions? Or will they slide back into the bad habits of business unionism that characterized the UAW of the past—and far too many unions of the present?

A union contract is a snapshot of the balance of power at the time it is negotiated, a truce in the class war. Only a fool would believe that auto executives will sit pat while UAW members implement the new contractual provisions. The bosses also have four and a half years—a lot of time—to find and exploit any weaknesses or ambiguities in the new agreements and push back against today’s gains. It will take relentless work by members to enforce their contract wins, especially those related to organizing workers at new plants, where company resistance is sure to materialize, notwithstanding the words on paper.

Finally, the third question to be answered is what sort of working-class movement will emerge from the autoworkers’ win.

In announcing that the UAW contracts will expire the day before May Day 2028, Fain laid down a challenge to all unions. May Day, he noted, is more than a day of commemorating worker struggles, “it is a call to action.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →“We invite unions around the country to align your contract expirations with our own, so that together we can begin to flex our collective muscles. If we’re truly going to take on the billionaire class and rebuild the economy so that it starts to work for the many and not the few, then it’s important that we not only strike, but that we strike together,” he said.

This is a powerful declaration of class struggle, truly remarkable to hear from a national union leader in the 21st century. Imagine not tens or hundreds of thousands but millions of workers uniting to strike together in 2028; imagine the bold demands that we could put forward. Imagine how hard the billionaire class and its politicians will fight to block us at every turn.

Fain’s May Day call to action is simply an idea—for now. Nearly all his labor leadership counterparts—the presidents and officers of the national unions, the leaders and top staff at the AFL-CIO—are manifestly unsuited to answer this call. They are far too ensnared in the turbid swamps of Democratic Party politics and business-as-usual unionism to be capable of even supporting that fight, much less leading it.

But Fain’s clarion call to action is certain to excite rank-and-file workers throughout the country who are struggling under the hammer blows of low wages, soaring rents, brutal bosses, crumbling public services, and a turbulent planet. Fain has issued us all a challenge. How ordinary workers respond, how they put their shoulders to the collective wheel in the coming months to organize autoworkers and other workers, how they challenge one another to act boldly and envision new horizons, will determine whether we look back in 2028 at Fain’s May Day call as a mere rhetorical flourish—or the start of something very big.

Disobey authoritarians, support The Nation

Over the past year you’ve read Nation writers like Elie Mystal, Kaveh Akbar, John Nichols, Joan Walsh, Bryce Covert, Dave Zirin, Jeet Heer, Michael T. Klare, Katha Pollitt, Amy Littlefield, Gregg Gonsalves, and Sasha Abramsky take on the Trump family’s corruption, set the record straight about Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s catastrophic Make America Healthy Again movement, survey the fallout and human cost of the DOGE wrecking ball, anticipate the Supreme Court’s dangerous antidemocratic rulings, and amplify successful tactics of resistance on the streets and in Congress.

We publish these stories because when members of our communities are being abducted, household debt is climbing, and AI data centers are causing water and electricity shortages, we have a duty as journalists to do all we can to inform the public.

In 2026, our aim is to do more than ever before—but we need your support to make that happen.

Through December 31, a generous donor will match all donations up to $75,000. That means that your contribution will be doubled, dollar for dollar. If we hit the full match, we’ll be starting 2026 with $150,000 to invest in the stories that impact real people’s lives—the kinds of stories that billionaire-owned, corporate-backed outlets aren’t covering.

With your support, our team will publish major stories that the president and his allies won’t want you to read. We’ll cover the emerging military-tech industrial complex and matters of war, peace, and surveillance, as well as the affordability crisis, hunger, housing, healthcare, the environment, attacks on reproductive rights, and much more. At the same time, we’ll imagine alternatives to Trumpian rule and uplift efforts to create a better world, here and now.

While your gift has twice the impact, I’m asking you to support The Nation with a donation today. You’ll empower the journalists, editors, and fact-checkers best equipped to hold this authoritarian administration to account.

I hope you won’t miss this moment—donate to The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

Anger at Corporate Power Is Everywhere Anger at Corporate Power Is Everywhere

It should guide the Democrats.

Honoring the Progressives Fighting for Our Democracy Honoring the Progressives Fighting for Our Democracy

These activists and artists, pastors, and political leaders know what has always been true: The people have the power.

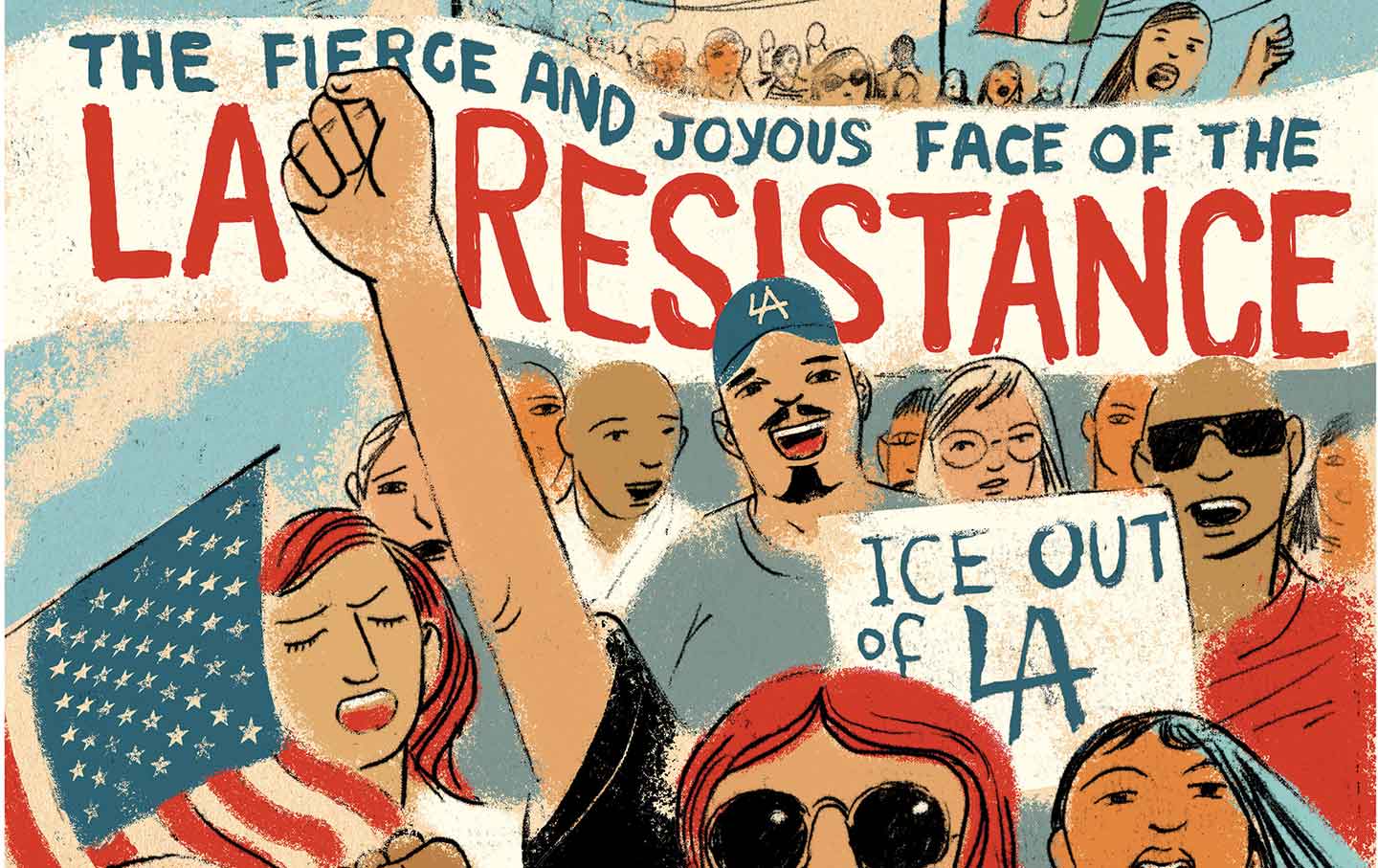

The Fierce and Joyous Face of LA Resistance The Fierce and Joyous Face of LA Resistance

What we can learn from a great American city’s refusal to bend to Trump’s invasion.

San Diego’s Clergy Offer Solace to Immigrants—and a Shield Against ICE San Diego’s Clergy Offer Solace to Immigrants—and a Shield Against ICE

In no other US city has the faith community mobilized at such a large scale to defend immigrants against the federal government.

If Condé Nast Can Illegally Fire Me, No Union Worker Is Safe If Condé Nast Can Illegally Fire Me, No Union Worker Is Safe

The Trump administration is making employers think they can ignore their legal obligations and trample on the rights of workers.

The Counteroffensive Against Operation Midway Blitz The Counteroffensive Against Operation Midway Blitz

How Chicago residents and protesters banded together against the Trump administration's immigration shock troops.