Yale Students Voted to Divest, but What’s Next is Unclear

The referendum calls on the school to divest its $41 billion endowment from military weapons manufacturing firms, yet the power to do so is in the hands of the board of trustees.

A student referendum asking Yale University to disclose and divest its investments in military weapons manufacturing and reinvest in programs to support Palestinian studies and scholars passed resoundingly last Sunday.

The Yale College Council, which administered the referendum, will now send Yale president Maurie McInnis a letter regarding the results. Yet beyond this symbolic action, the ramifications of the student referendum are unclear. The power to disclose and divest Yale’s endowment holdings lies entirely in the hands of just 16 individuals: the Yale Board of Trustees, or the Yale Corporation.

More than 83 percent of student voters answered “yes” on the first question, which asked if Yale should disclose investments in military weapons manufacturers and suppliers, including those arming Israel. The second question asked if Yale should divest from such companies, passing with 76 percent of the vote. The third question asked if Yale should invest in Palestinian scholars and students to fulfill its “commitment to education,” with 79 percent of voters in favor.

Well over one-third of the student body voted “yes” on all three resolutions, clearing the threshold needed for the referendum to pass. Almost 3,400 students—nearly 50 percent of the Yale undergraduate student body—voted over the span of four days.

“The effort to pursue a referendum was about showing what we’ve known to be true this entire time, which is that disclosure, divestment, and investment in Palestinian studies aren’t fringe positions, the way that a lot of the media discourse has tried to put it,” said Karsten Rynearson, an organizer with the Sumud Coalition, a group of Yale students that organizes in support of Palestinian liberation and proposed the referendum. “They’re incredibly popular positions on this campus.”

The results align with similar referendums at other universities. At Columbia, students voted overwhelmingly last April to divest from Israel. At Princeton, a referendum calling for the university to disclose and divest from weapons manufacturing passed late November.

Yale University’s endowment totals over $41 billion—the largest source of revenue in the university’s budget. Less than 1 percent of this money is publicly traceable through the school’s filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The vast majority of the endowment is distributed to private asset managers, and is not bound by the same public disclosure requirements as the university.

The Endowment Justice Coalition, a member organization of Sumud, identified several of the university’s asset managers with ties to weapons manufacturers using filings from the Internal Revenue Service. The asset managers include JLL Partners, a private equity firm connected to General Dynamics and Lockheed Martin, and Farallon Capital, a hedge fund with ties to HowMet Aerospace, which manufactures several key parts of Israel’s F-35 fighter aircraft. EJC argues that Yale’s undisclosed endowment holdings likely conceal additional connections to the weapons manufacturing industry.

“As the genocide in Gaza continues, our institution of learning should not be committed to mass death,” said Caroline Huber, a junior at Yale and a a member of Yale Jews for Ceasefire, which organizes with the Sumud Coalition. In social media posts, organizers supported the referendum with the slogan: “Books, Not Bombs.”

Sumud, formed earlier this academic year, includes several organizations that organized the three-day encampment on Yale’s central Beinecke Plaza last spring, which ended when Yale Police dispersed the encampment and arrested at least 47 protesters. “Sumud,” an Arabic word that can be translated as “steadfastness,” is a term associated with the 1967 Six-Day War and broader Palestinian liberation struggle.

To initiate the student body-wide referendum administered by the Yale College Council, Sumud launched a social media campaign to secure signatures from 20 percent of the student body and over half of the YCC Senate. Referendum voting was open for four days last week, during which organizers postered around campus, tabled outside dining halls, and hosted an event with performances from student groups to boost engagement. Over 50 student organizations—from dance groups to publications to cultural associations—endorsed the referendum.

Sumud has argued that divestment would be particularly meaningful coming from Yale, given the influence of the “Yale Model” for institutional investing. The model, developed in the 1980s, emphasizes investments in private markets, hedge funds, and real estate—an endowment investment strategy that has been adopted by Harvard, Princeton, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and many other universities.

Socially motivated divestment has precedents at Yale. In 2018, the Yale Corporation announced that it would prohibit investments in assault weapon retailers, citing the “grave social injury” caused by mass shootings. Between 1978 and 1994, in response to apartheid, the university divested around $23 million from 17 companies doing business in South Africa (Yale Corporation lifted restrictions on investments tied to South Africa in 1994). In 2006, the corporation divested from oil and gas companies operating in Sudan. In the past decade, the corporation has also restricted investments in specific private prison operators and fossil fuel companies.

Last spring, the Advisory Committee on Investor Responsibility, a body that advises the corporation on policies related to ethical investing, ruled that investment in weapons manufacturing did not constitute a threshold of “grave social injury” needed to justify divestment.

Divestment organizers at other universities have seen significant movement on the issue of disclosure. Last April, Northwestern agreed to answer questions about specific current holdings within 30 days. Last May, the University of California–Riverside signed an agreement to work toward “full disclosure” of the companies and size of investments in their portfolio.

Opponents to last week’s referendum argued that divestment would be legally and financially risky, as well as geopolitically misguided. The referendum’s “Against Statement”—a compilation of statements written by students and summarized using an AI tool—argued that divestment ignores “the complexities of global defense needs” and that weapons by US defense manufacturers are used to defend democracy and counter authoritarian regimes.

In an Instagram post, the organization Yale Friends of Israel wrote that the referendum was a “call for divestment from companies that help U.S. allies including but not limited to Ukraine, Taiwan, and Israel, who defend themselves against those who want to destroy them and their democracy.” Friends of Israel did not respond to a request for comment.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →In its statement supporting the referendum, Sumud argued that “companies selling bombs and fighter jets to ‘good states’ do not excuse persistent sales to states violating international law.”

For organizers, the results affirmed widespread support for divestment among the student body. “Our movement is definitely the popular movement, and I think the Yale student body has certainly demonstrated their values with this referendum,” said Huber. “So it really is up to the trustees to listen to the students whose institution they rule over.”

Time is running out to have your gift matched

In this time of unrelenting, often unprecedented cruelty and lawlessness, I’m grateful for Nation readers like you.

So many of you have taken to the streets, organized in your neighborhood and with your union, and showed up at the ballot box to vote for progressive candidates. You’re proving that it is possible—to paraphrase the legendary Patti Smith—to redeem the work of the fools running our government.

And as we head into 2026, I promise that The Nation will fight like never before for justice, humanity, and dignity in these United States.

At a time when most news organizations are either cutting budgets or cozying up to Trump by bringing in right-wing propagandists, The Nation’s writers, editors, copy editors, fact-checkers, and illustrators confront head-on the administration’s deadly abuses of power, blatant corruption, and deconstruction of both government and civil society.

We couldn’t do this crucial work without you.

Through the end of the year, a generous donor is matching all donations to The Nation’s independent journalism up to $75,000. But the end of the year is now only days away.

Time is running out to have your gift doubled. Don’t wait—donate now to ensure that our newsroom has the full $150,000 to start the new year.

Another world really is possible. Together, we can and will win it!

Love and Solidarity,

John Nichols

Executive Editor, The Nation

More from The Nation

Honoring the Progressives Fighting for Our Democracy Honoring the Progressives Fighting for Our Democracy

These activists and artists, pastors, and political leaders know what has always been true: The people have the power.

Anger at Corporate Power Is Everywhere Anger at Corporate Power Is Everywhere

It should guide the Democrats.

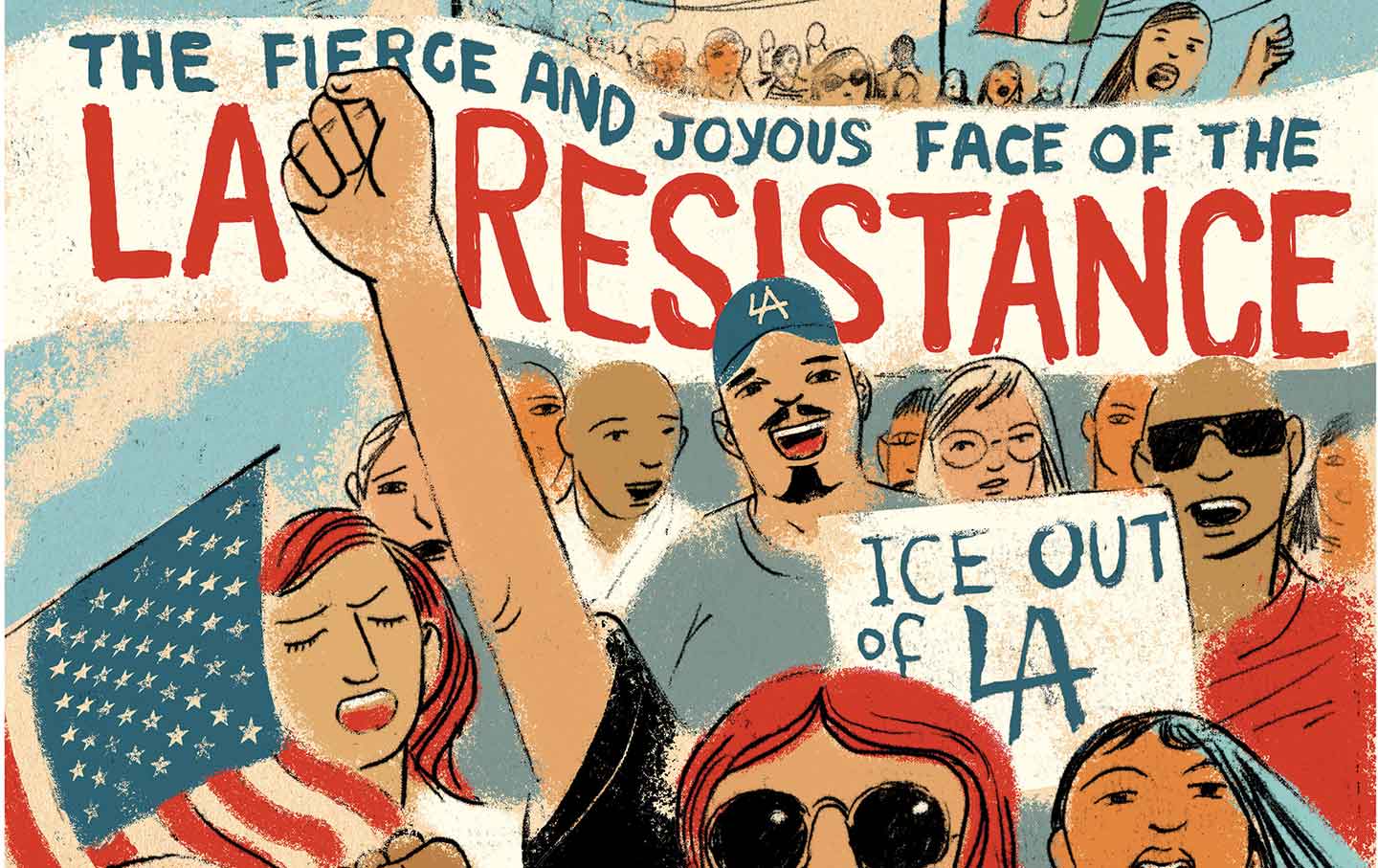

The Fierce and Joyous Face of LA Resistance The Fierce and Joyous Face of LA Resistance

What we can learn from a great American city’s refusal to bend to Trump’s invasion.

San Diego’s Clergy Offer Solace to Immigrants—and a Shield Against ICE San Diego’s Clergy Offer Solace to Immigrants—and a Shield Against ICE

In no other US city has the faith community mobilized at such a large scale to defend immigrants against the federal government.

If Condé Nast Can Illegally Fire Me, No Union Worker Is Safe If Condé Nast Can Illegally Fire Me, No Union Worker Is Safe

The Trump administration is making employers think they can ignore their legal obligations and trample on the rights of workers.

The Counteroffensive Against Operation Midway Blitz The Counteroffensive Against Operation Midway Blitz

How Chicago residents and protesters banded together against the Trump administration's immigration shock troops.