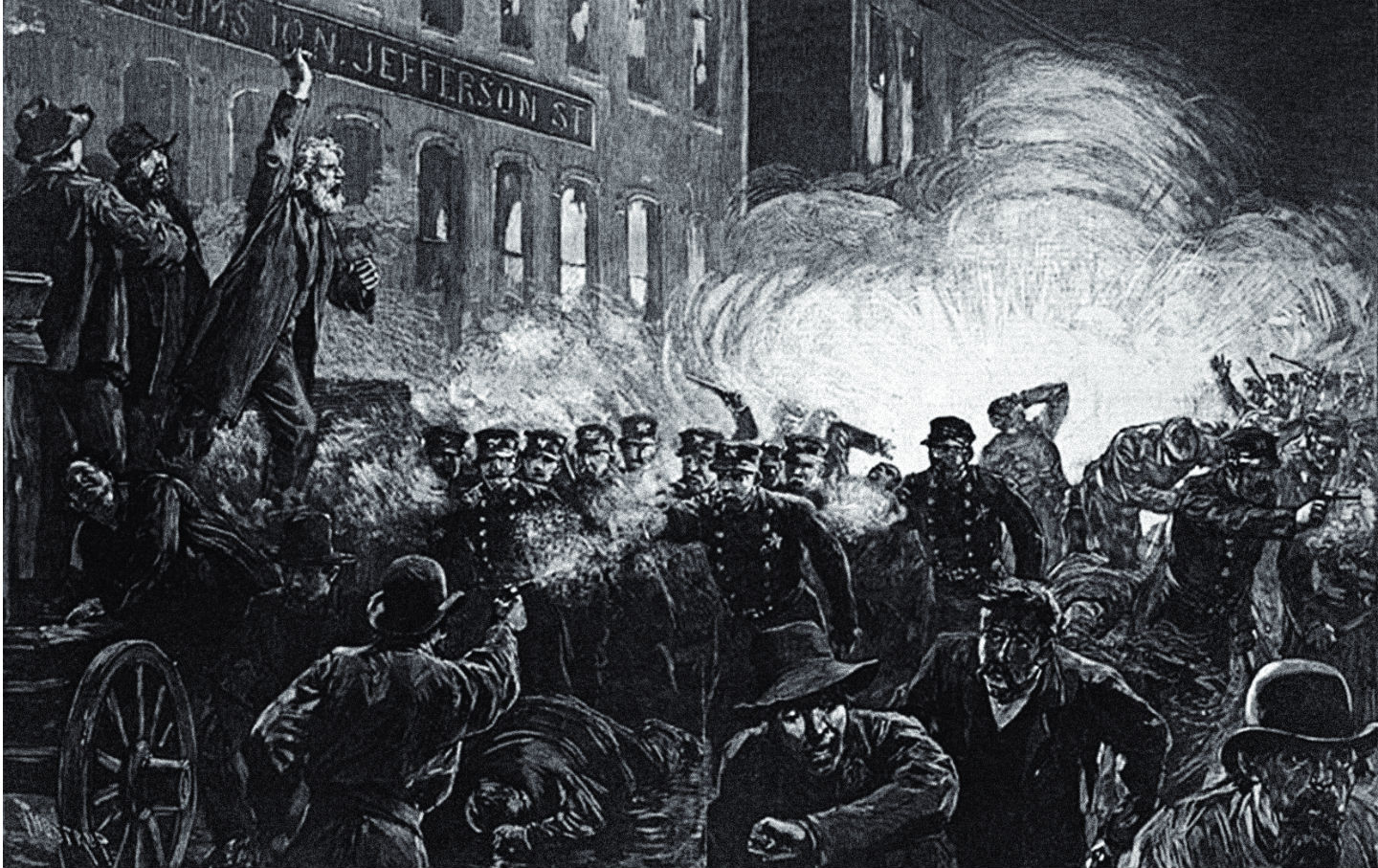

(Thure de Thulstrup, Harper's Weekly, 1886)

This article is part of The Nation’s 150th Anniversary Special Issue. Download a free PDF of the issue, with articles by James Baldwin, Barbara Ehrenreich, Toni Morrison, Howard Zinn and many more, here.

The Execution of the Anarchists

Editorial (E.L. Godkin) Excerpted from the November 10, 1887 Issue

It is now a year and a half since the bomb-throwing in Chicago. During the following six months people’s minds were occupied with the horrors of the resulting slaughter and maiming of the police, about forty of whom were killed or disabled in the discharge of their duty, and with the devilish malignity of the attack on them. At that time nobody—not even, we think, the firmest opponents of capital punishment—ventured to suggest that there was any place in this world for the bomb-throwers, or that the removal from it of such tigers was not a solemn duty to human society.

Since then, however, a good many people—some of them clergymen, some philanthropists, and some simply soft-headed people who sign all papers presented to them which do not impose pecuniary obligations—have had time to forget all about the police, and all about social security, and all about the Anarchists’ teachings and aims, and are trying to get Governor Oglesby to commute the sentences of the men now awaiting execution.

Our traditional Anglo-Saxon respect for free speech is based on the assumption that public speech is always intended in free countries to persuade people into agreement with the speaker for purposes of legislation, and that the agreement aimed at is therefore a lawful one. The notion that we must tolerate speech the object of which is to induce people to break up the social organization and abolish property by force, is historically and politically absurd. The notion that we must not do whatever is necessary to prevent men’s publicly recommending murder and arson, because they are sincere in thinking murder and arson good means to noble ends, is worse than absurd. It is, as we see, full of danger for everything we most value on earth.

It is a great pity that we cannot shut up the mouths of the Anarchists by love. But as we cannot shut them up by love, we must do it by fear, that is, by inflicting on them the penalties which they most dread; and the one most appropriate to their case when they kill people, is death. The frantic exertions they are making just now to escape the gallows, and the joy with which they would welcome a “life sentence,” shows clearly that the gallows is the punishment the case calls for. For violent incitements to murder and pillage, imprisonment will doubtless suffice; but for actual murder and pillage there is nothing likely to prove so effective a deterrent as death. Those who oppose this view can only do so successfully by maintaining that society has no right to defend its own existence, and that murder and arson are evils only when the murderer’s motives are low and selfish; that if he can show that he means well, and has at heart the elevation of the poor, he should be treated with the respect due to prophets and apostles. If the propagators of these grotesque fancies only knew the encouragement they were giving to the contempt for law which makes both the rich briber and semi-barbarous lyncher the curse of American politics at present, we feel sure they would pause in their efforts to save the community the loss of the vagabonds and ruffians who are now awaiting execution at Chicago.

E.L. Godkin (1831–1902) was the founding editor of The Nation and, after selling the weekly in 1881, editor of the New-York Evening Post.

* * *

Encounter: E.L. Godkin and Rochelle Gurstein

The Right to Privacy

Editorial (E.L. Godkin) December 25, 1890

The Passion for Notoriety

Rochelle Gurstein April 6, 2015

* * *

Editorial November 29, 1894

The NationTwitterFounded by abolitionists in 1865, The Nation has chronicled the breadth and depth of political and cultural life, from the debut of the telegraph to the rise of Twitter, serving as a critical, independent, and progressive voice in American journalism.