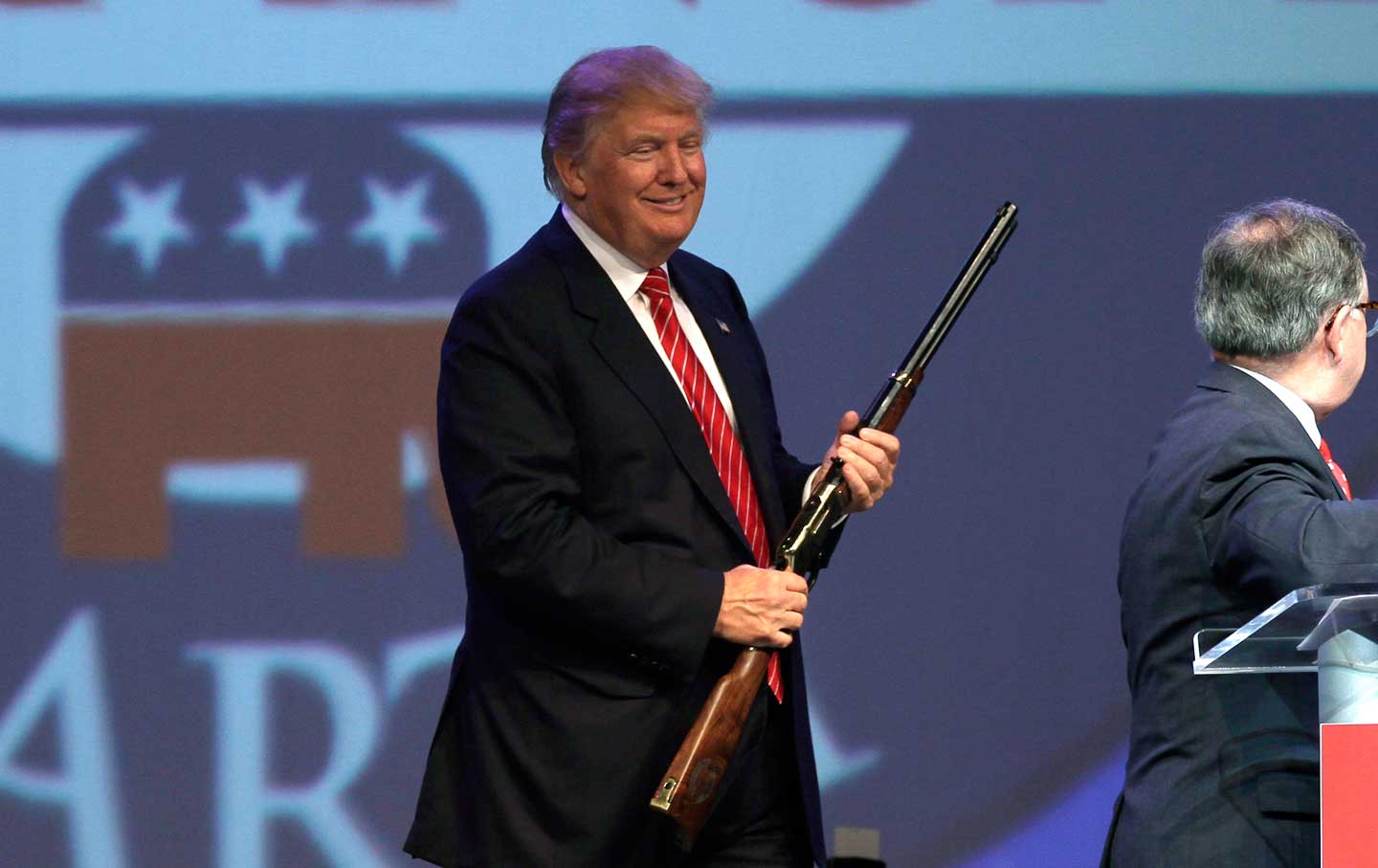

Republican presidential hopeful Donald Trump holds a rifle presented to him at the Republican Party of Arkansas Reagan Rockefeller dinner in Hot Springs, Arkansas on July 17, 2015. (AP Photo/Danny Johnston)

The horse race started earlier this time, and political reporters are having a good time keeping up with the goofiness. On the right, sixteen wannabes are prancing around the paddock. On the left, the Clinton dynasty claims the throne as rightful inheritance of primogeniture. The media mob, meanwhile, gets to play racetrack tout nearly every day, scolding flawed performances and concocting what-if scenarios about how various miscues and errors might affect the election returns in 2016.

These dope stories are known among older reporters as “thumb-sucking.” Not much reporting is needed, because who will remember half-baked predictions fifteen months later, when the nation actually votes?

This new column for the election season, Naked Democracy, will not spend too much time on horse-race chatter. Instead, I have in mind a running inquiry into things the political order won’t talk about. I mean the big issues and ideas, the neglected opportunities and deliberate falsehoods that confront the nation. The deeper disorders are abundantly visible, but largely evaded or even actively concealed by the money-drenched campaigns. Their advisers reduce citizens to data, then carefully test-market issue content so prudent candidates will know what not to mention.

Getting naked means peeling away the folklore and cardboard characters, the distorting propaganda and trivial political intrigues, so we can see the bare bones of our larger predicament. (The column title is also an admiring nod to Yves Smith’s Naked Capitalism blog.)

The soaring birth rate for GOP candidates actually reflects the breakdown of the party system. In olden days, when the political parties were real organizations of real people and not mere mail drops for donor money, regional and national party bosses used to screen potential candidates. Now the billionaires fill that role. The reason we have so many Republicans running for 2016 is that so many billionaires want to finance their own personal racehorse.

The golden-haired Prince of Trump has created his own spotlight, and he’s scaring the crap out of party regulars. The Donald took up some of the GOP’s favorite prejudices and repackaged them as woozy barstool bigotry. His harsh talk should make Democrats nervous too, because it is broadly appealing.

Trump is performing a wicked parody of America’s dysfunctional democracy, mocking a system in which candidates do their best to avoid saying what they really think. If a wannabe should accidently speak the truth, the media will punish his “gaffe.”

Who says you can’t dump on Mexicans? Or brag obnoxiously about your personal wealth? Candid Donald even admits he is a superior guy, smarter and tougher, more fun to be around. Lots of people get the joke and laugh along with him. Voting for him, maybe not. My only prediction for 2016 is that at some point Prince Trump will turn back into a frog.

But The Donald is on to something true when he ridicules the unconvincing burlesque of presidential politics. People are not in awe when both political parties have become wobbly institutions, confused and insecure and divided internally. Their core constituencies no longer trust the leaders and rebel against a political establishment that has repeatedly misled or betrayed them. The largest pool of available voters is now the people who stay home. They learned their indifference and confusion from the babble of election campaigns.

According to newsies, Hillary Clinton has already won the Democratic nomination. But Hillary has to tiptoe through a minefield of doubt. She must make nice to her party’s skeptical lefties, but without disturbing the Wall Street money guys who finance Clinton campaigns. Her cautiously crafted statements of purpose sound like somebody watered her drink.

“Hillary is not bad,” Representative Michael Capuano of Massachusetts observed. “It’s just, all of us know she is having an excitement problem. We all know that. It’s not a secret.”

Actually, I think it is American democracy that has the “excitement problem.” The smoke and mirrors of candidates and campaigns have lost their thrill. Too many Americans have figured out the game is not about them. People have been burned before by the peppy slogans and mendacious promises. They are on stage merely as extras. People know presidential elections matter greatly, but they also know governing elites are not telling the hard truth about the American predicament.

Our great national sickness is the deteriorated condition of American democracy itself. Politicians don’t bring this up. It’s a turn-off for voters. How can they ask people to vote for them if they have to explain that the promise of self-governing citizens is a nostalgic remnant, no longer practical? The permanent subculture of political professionals resembles a family that has contracted a dread disease but doesn’t want to tell the neighbors. Too late. People already know the system is failing.

One fundamental reality that gets virtually no mention by regular politicians is the implosion of American domination. For half a century, Washington steered the world, for better or ill, but that proud role is effectively obsolete. Our sprawling military presence drags the nation into occasional wars, and taking sides in other people’s enmities is a costly burden. But how does the United States gracefully back away without looking like just another declining empire?

The globalized economic sphere, led for decades by Washington, has shifted economic power in similar ways and deepened inequalities at home. The American exceptionalism touted by right-wing patriots has taken on morbid meanings: declining industrial influence, burgeoning debts, deteriorating middle class. Liberal Democrats are pushing a promising agenda to improve the condition of workers and families, but they don’t mention that these proposals are attempting to catch up with social guarantees that other developed nations have provided their citizens for many years.

The next American era does not need to be hard times. It could be vastly liberating and prosperous for all. But first the political order has to let go of the past. We are at an end-of-era reckoning. Ordinary people seem to grasp this better than most leaders.

A vibrant democracy would be arguing over these matters and proposing deeper reforms. Serious citizens who yearn for honest discussion are mostly provided advertising slogans and tough-guy promises. Every four years, we tell ourselves (or are assured by political cheerleaders) that the next president will start over and save us from errors and evasions. I subscribe to a sterner kind of optimism.

We will not be saved, I suggest, unless the people step up for themselves and actively challenge the power and orthodoxy of the reigning interests. Things will change only if people decide to take personal responsibility for transforming the country and creating a more promising future. This is highly unlikely in 2016. It will take more than one election to get over the national hubris and find new directions for our pride and ingenuity. But perhaps people can start digging out in this election cycle, regardless of what politicians try to tell us or which ones win higher office.

I believe this is possible, despite awesome concentrations of wealth and power. Cynics would say it’s impossibly dreamy, but look closely at the course of American history and you will find that society’s greatest breakthroughs in social progress and economic equity were achieved only when people mobilized and struggled massively on behalf of radical departures from the status quo. Sometimes winning elections, but also sometimes losing. The “great men” celebrated by conventional historians were powered by people in motion—popular uprisings that altered the social fabric and expanded the obligations of government to we, the people.

I will go further and suggest that our country is once again approaching a fundamental turning point. Popular mobilizations are already under way on numerous fronts, both inside and outside party ranks. They are driven by people of every stripe and color—both angry and idealistic. The outcome of next year’s elections is unlikely to satisfy these disparate new energies from below, but the elections won’t turn them off, either.

I propose a slightly different way of looking at 2016. On the surface, it looks like same-old, same-old—the familiar contest of Rs against Ds with a few well-known family names thrown in. But this time I can imagine formations of disparate people at large, though scattered and without a proper name, emerging as a new “third rail” in American politics. An unorganized, rump aggregation of angry idealists, whether from left or right or both, people who still believe in small-d democracy and get a kick out of talking back to power. Their formless power threatens both of the entrenched and deteriorating parties.

But how could I imagine democratic revival if so many dispirited Americans no longer believe democracy is possible? Cynics have it wrong. The great paradox of our time is that while the formal democracy of elections and parties was being captured and enfeebled by wealthy economic interests, the people who made their own politics in the streets were scoring astonishing victories.

Think of the civil rights movement in the springtime of its great triumph. Or the feminists who taught us a generation ago that the personal is political. Or the social liberation engineered by gays and lesbians from ancient prejudices that blighted their lives. Or the mobilization of Latinos, fighting to overcome exploitative immigration laws with or without an act of Congress.

Yes, these movements had some friends in power who assisted, but in every case, it was the people who liberated themselves. How did they do it? Through hard struggle, of course, as well as endless internal arguments over strategy.

But the essential quality in all these movements was, first, they never lost intimate identification with their own rank and file, and, second, they never stopped confronting the people in power—including friendly allies and presidents—with hard-nosed demands. In other words, they refused to act like bleeding-heart supplicants begging for favors. They acted like citizens. They made life difficult for the powerful. Think of Martin Luther King Jr. staring down Lyndon Johnson. Think of today’s Latino leaders nose-to-nose at the White House with Barack Obama.

Ordinary people can find the strength to do hardball politics against the mighty when they know the struggle is not just about “politics” but about life itself. From my years of experience as a reporter, I got to know a lot of these principled agitators. On the whole, they are a tough crowd—used to losing but not to giving up.

Odd as it sounds, I came to realize that what motivated them was love. They were not sentimentalists. But first they had to learn to love themselves. Once they could take themselves seriously as human beings, then they could love their family and friends, then their community, then their country.

What’s love got to do with it? Maybe love is what’s missing from our democracy.

William GreiderWilliam Greider is The Nation’s national-affairs correspondent.