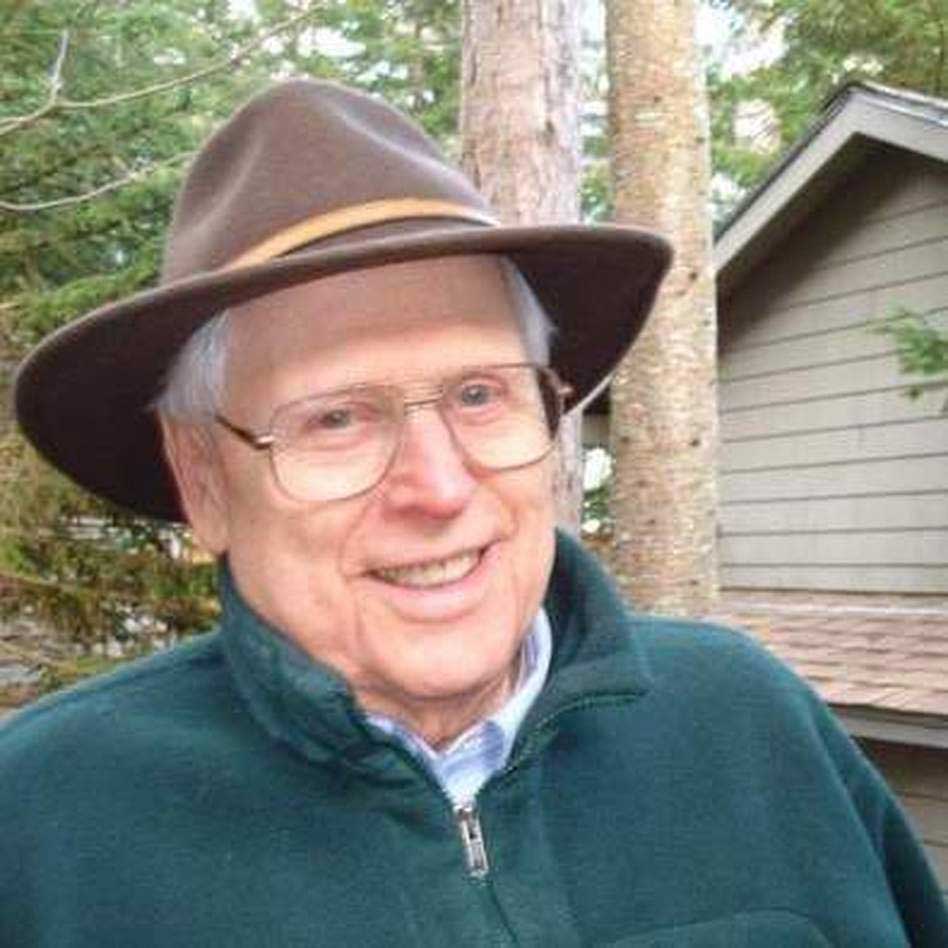

Renowned author and journalist Nicholas von Hoffman.

The phone would ring in the early evening when I was cooking dinner and my wife, Eleanor, would pick up the receiver and sigh. “It’s Nick, darling. Why don’t you tell him you’ll call him back?”

In the interest of domestic calm, and dinner, I sometimes called back, but rarely. Chats with my friend of 40 years, Nicholas von Hoffman, were too much fun. Who would not skip soup for Nick’s rendering of “the niggling noodleheads of mediadom” covering the White House? Or, at election time, for his rant on the “journalistic springer spaniels and Irish setters who course the countryside, coming to attention at each new trend and tremor of taste and opinion”? Or his scorn for military pundits, “Why can’t they tell us where the front lines are in Syria, for God’s sake”? Or, his theory, with a reference to Julius Caesar, on the “upside to Piracy”? He would always end the call asking, “What’s for dinner?”

A month ago, the phone stopped ringing, and last week Nick died at the age of 88, his mind still alert, but his body exhausted from strenuous, and very successful, exertions on so many fronts—newspapers, radio, magazines, books, nonfiction and fiction, a bestseller, several plays, and a libretto.

His achievements have been celebrated. He wrote for the big newspapers, starting on the Chicago Daily News, and then The Washington Post for 10 years. Post editor Ben Bradlee praised him as one of the “landmarks in the early timid years of the New Journalism.” Nick, who never went to college, fell into journalism. “What else? I had no useful skills, I was bootless and rootless.” He never saw himself as producing any new art form, just the old methods practiced by Hearst, Pulitzer, and Mencken. The readers had to be entertained, as well as informed. “You got to get people to read the damn thing.”

His syndicated column was certainly read. He upended one American cherished ideal after another, and put so many Washington high-ups in his crosshairs that the Post’s owner, Kay Graham, who was a fan, declared how much simpler her life would be without him. Shortly, he “sort of floated away,” as he put it. It was the start of several disengagements by proprietors, editors, and producers, who couldn’t take the heat from the von Hoffman flamethrower.

He was a contemporary of the British journalist Henry Fairlie, who made a career out of biting the hand that fed him. “They were dangerous, courageous, men,” recalled Leon Wieseltier, then literary editor of The New Republic. “They could be savage, like caricaturists. The top was there to go over.”

Nick’s most famous dismissal came in 1974 from CBS’s 60 Minutes after he called Nixon, on the air, “a dead mouse on the kitchen floor that everyone was afraid to touch and put in the garbage.” Nothing by today’s standards, but a fireable offense back then, as it turned out.

It was, he protested, only a statement about the president’s political situation. It was also his “15 or 25” minutes of fame, that precarious moment when mere reporters suddenly become stars, and, as he put it, “your head no longer fits any hat in the closet.” That never happened to Nick. He was content with what he called his “modest talent and a happy-go-lucky streak.”

The novelist Mary Breasted recalled how in 1980, the year Ronald Reagan was elected, Nick was on a public TV roundtable with, in his view, an uptight host. At one point, bored and ready for action, he leaned across the mic and yanked the host’s tie, to loosen him up a bit. The horrified producer pulled the plug and the screen went blank, only to be replaced by a new panel-in-waiting whose members were giggling uncontrollably about what they had just seen. As he left the studio, Nick called out, “I’ve been kicked off better networks.”

As Nick ran out of employers, he decamped permanently from New York to Maine. He rarely traveled, and only briefly abroad—to England, France, and Ireland. To be a member of Nick’s extended phone gang was to share his blasts, his humanity, his vivid sense of justice, and his laugh, a bellow of genuine mirth. The calls came at least once a week, sometimes more frequently.

He would not be pinned down on his politics, which were unverifiable. “I have a reputation for being a howling liberal, not true,” he told C-Span. He voted for Eisenhower and then Nixon (“I got suckered by his anti-war talk”). He was happy to be published by the libertarian, Koch-funded Cato Institute, as long as they tolerated his mischief. When pushed, he would say he believed in what he called “devolved government.”

Donald Trump’s cruel and chaotic second term is just getting started. In his first month back in office, Trump and his lackey Elon Musk (or is it the other way around?) have proven that nothing is safe from sacrifice at the altar of unchecked power and riches.

Only robust independent journalism can cut through the noise and offer clear-eyed reporting and analysis based on principle and conscience. That’s what The Nation has done for 160 years and that’s what we’re doing now.

Our independent journalism doesn’t allow injustice to go unnoticed or unchallenged—nor will we abandon hope for a better world. Our writers, editors, and fact-checkers are working relentlessly to keep you informed and empowered when so much of the media fails to do so out of credulity, fear, or fealty.

The Nation has seen unprecedented times before. We draw strength and guidance from our history of principled progressive journalism in times of crisis, and we are committed to continuing this legacy today.

We’re aiming to raise $25,000 during our Spring Fundraising Campaign to ensure that we have the resources to expose the oligarchs and profiteers attempting to loot our republic. Stand for bold independent journalism and donate to support The Nation today.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

His reputed “left-wing perspective” grew out of his first job as a community organizer in Chicago, working for the social activist Saul Alinsky. He learned from the master how to be “a constructive troublemaker.” He wrote a biography of Alinsky, published by Nation Books, and a stream of Nation articles spanning two decades targeting presidents, politicians, banks, lawyers, jackleg preachers, authors who needed taking down a peg or two, and of course, the “niggling noodleheads” of the media.

He beefed against junk politics as usual—“the ups and downs and bumpsy-daises of war and peace, of boom and bust.” But he always saw hope of radical change. In a 1978 piece for The Nation, he wrote, “Wisps of other ideas and values have not been completely voided from the hermetic social sphere. Some of us can still cause trouble, so we can hope some of us will.”

If only he had been fit enough to take on Trump.

Peter PringlePeter Pringle was a correspondent for British newspapers during the Cold War in Washington and Moscow. He has written for The Nation on chemical and biological weapons aided by research from the Harvard-Sussex databank.