ZINA SAUNDERS

ZINA SAUNDERS

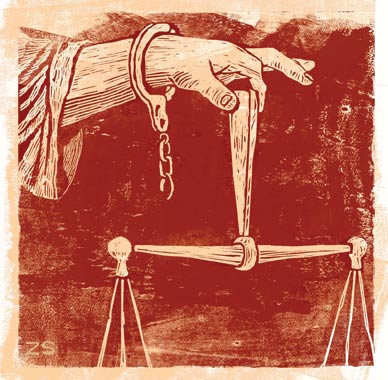

Federally funded legal services lawyers for poor people have been operating with one hand tied behind their back since Newt Gingrich and his brand of Republicans took control of Congress in the mid-1990s. Now that we have a Democratic president and Congress, it is time to roll back the restrictions that federal money brings–constraints that lawyers for paying clients do not encounter. In his detailed budget request for the coming year, President Obama proposes to repeal the most onerous of the strictures–a welcome step. Congress is currently considering the president’s proposals, and should enact them into law.

Legal services lawyers help low-income people stave off eviction, resist predatory lenders, protect themselves from domestic violence, obtain public benefits and deal with family issues. Federal funding was first provided as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty and is distributed by the federally chartered Legal Services Corporation. Well over half the full-time lawyers for the poor work for organizations that receive federal money, so the limits on what they can do have a serious impact on a field that is already greatly understaffed.

The impulse to regulate lawyers for the poor is of course not unrelated to our proclivity to regulate the poor in other ways, especially those poor people we deem undeserving. Various interests began trying to curb legal services for poor people from the moment federal funding was first provided. Agribusiness and other businesses that made money on the backs of the poor, as well as some public officials, thought it was outrageous that taxpayer money could finance lawsuits to make them obey the law as it related to poor people.

Even so, major limitations on federally supported legal services activities were not adopted until the Gingrich revolution, although funding was cut severely by President Reagan (and again during the Gingrich era). Advocacy by the American Bar Association and bipartisan efforts by members of Congress, especially lawyers, kept the program largely free from such limits for a surprisingly long time.

Perhaps the best-known restriction is the ban on class-action suits. Another that has had a big impact is the bar on reimbursement of attorneys’ fees in cases where federal or state law lets every other successful litigant collect them (civil rights suits are a prime example). But the list is quite long. Others apply to specific client groups and categories of cases and activities–prison inmates, abortion cases, undocumented and many legal immigrants, redistricting cases and legislative and administrative advocacy generally. The most damaging, though, is the one that makes all the restrictions apply to money the legal services organization receives from sources other than the federal government.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →

President Obama’s proposal calls for repeal of what are perhaps the most damaging federal-funding restrictions: those that apply to other sources of funding; the bar on attorneys’ fees, which reduces the already parched supply of lawyers for the poor; and the ban on class actions. If enacted, the repeal would constitute a welcome boost to low-income people’s access to justice.

The response from Congress so far has been mixed. The House voted to repeal only the restriction on reimbursement of attorneys’ fees, while the Senate Appropriations Committee voted to eliminate almost all restrictions on use of nonfederal funds as well as the restriction on attorneys’ fees, but only in cases brought with nonfederal funds. Once the Senate completes its work, the matter will go to a House-Senate conference committee to resolve the differences.

With current Congressional reforms still undecided, much more remains to be done in the future, including repeal of all the restrictions.

Federal funding, which dropped to $278 million during the Gingrich era, has crept back upward, reaching $390 million this year. President Obama has requested $435 million for fiscal year 2010, to which the House has added $5 million, while the Senate committee is proposing a total of $400 million. But if funding for the program, which totaled $300 million in 1980, had kept pace with inflation, it would be about $750 million now. Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa, himself a former legal services lawyer, has introduced legislation to authorize annual legal services spending at that level.

The overall decline in federal support is the bad news. The somewhat better news is that other funding has come along in the meantime. Funding from a source called IOLTA, or Interest on Lawyers’ Trust Accounts (bank accounts into which lawyers temporarily deposit money pending completion of a commercial transaction), reached $215 million in 2008 (but will plummet in 2009 as interest rates decline to record lows). States also stepped into the picture, providing $212 million in 2008, and law firms, individual lawyers, foundations, attorneys’ fees (for the non-federally funded groups) and other sources brought total funding for civil legal assistance to about $1.2 billion last year. Pro bono help from lawyers provides another significant source of assistance.

Was the 2008 amount enough? Hardly, especially with the cuts occurring now in IOLTA and every other category of funding except the modest federal increases. Even before the current wave of reductions, federally funded lawyers estimated they were turning away one person for every one they served. Studies all over the country show that when one figures in those who need legal help but never try to obtain a lawyer, the total funding plus pro bono volunteering is meeting less than 20 percent of the need. And this when the number of poor people is rising along with recession-related legal needs (evictions, mortgage foreclosures, denials of public benefits and the like).

The funding mix described above tells an important story. In every large city there are many legal services organizations that receive no federal money. They are supported by private donations, attorneys’ fees, and state and local public appropriations, and amounts in each of these categories are shrinking. We need to focus not only on shoring up funding and pro bono efforts but on building in every state and community a real system of legal services on the ground, whether federally funded or not, that is transparent and accessible to people who need help.

Federal support (without restrictions and with more money) needs to include funding for training and backup expertise, another victim of the Gingrich attack. Fifteen national support centers and five regional training centers lost their federal funding at that time. The Legal Services Corporation should be not only a major funder of legal services but also the national quarterback and cheerleader for a sensible structure of services at state and local levels. State Access to Justice commissions (I happen to chair the commission in the District of Columbia) should play a pivotal role in the task of system-building.

Of course, there are even bigger issues involved here. Reagan- and Bush-era federal judges preside over the cases, and statutory protections eroded by Congressional action over that period often constitute the applicable law. Appointing good judges and enacting wise laws are crucial. And if we didn’t have so many poor people, we would have fewer people with the multiple legal problems that disproportionately affect the poor and more people who could afford to pay for legal assistance. Poverty is the underlying cause of the disproportionate legal problems of the poor.

Although we shouldn’t overestimate the payoff from repealing the restrictions on the federally funded lawyers, it is significant. President Obama’s proposals are important and should be enacted. The restrictions are meanspirited and punitive; they amount to a de facto violation of equal protection of the laws for low-income people. Hire a private lawyer and you’ll get the whole kit of tools and remedies. But go to the legal services office, and you’ll quickly find out that America thinks the poor are not as deserving as the rest of us.