Donald Trump’s outrageous, xenophobic, racist, and red-baiting rhetoric has become an American obsession. His vitriol has targeted members of Congress, migrants, refugees, and Latinx, Muslim, and black people. It has fanned the flames of racist violence and inspired acts of domestic terrorism. We’ve seen the devastating consequences in El Paso; in Gilroy and Poway, California; in Tallahassee, Florida; in Pittsburgh; and, of course, in Charlottesville, Virginia. Liberal pundits insist that Trump and the violence his rhetoric inspires are inconsistent with America’s founding creed. It is a common refrain among liberals—taken up most recently by former vice president Joe Biden, who said, “This is not who we are”—that the Muslim travel ban, the inhumane detention of asylum seekers and separation of their families, Trump’s white nationalist sympathies, and so on “do not reflect American values.” Put another way, Trump and his ilk are the exception to American exceptionalism.

Yet for communities that have long been subject to state violence, dispossession, massacre, mass imprisonment, and racial profiling, this is who we are. Trumpism is less an aberration than a more flagrant expression of long-standing US policy and practice. A democracy born of a settler-colonial society founded on indigenous dispossession and racial slavery, America isn’t so exceptional. Indeed, as the political theorist Michael Hanchard reminds us, all modern democracies were founded as ethnonational or racial states.

So who are we, really? The answer rests on our interpretation of history and on how we determine the circle of “we.” When confronting the violence of contemporary white supremacists, the “we” is unambiguous, with the history of white supremacy firmly outside the circle. But in the liberal land of San Francisco, where a left-wing artist created a public work that links America’s white supremacist and democratic traditions, things are a bit more complicated.

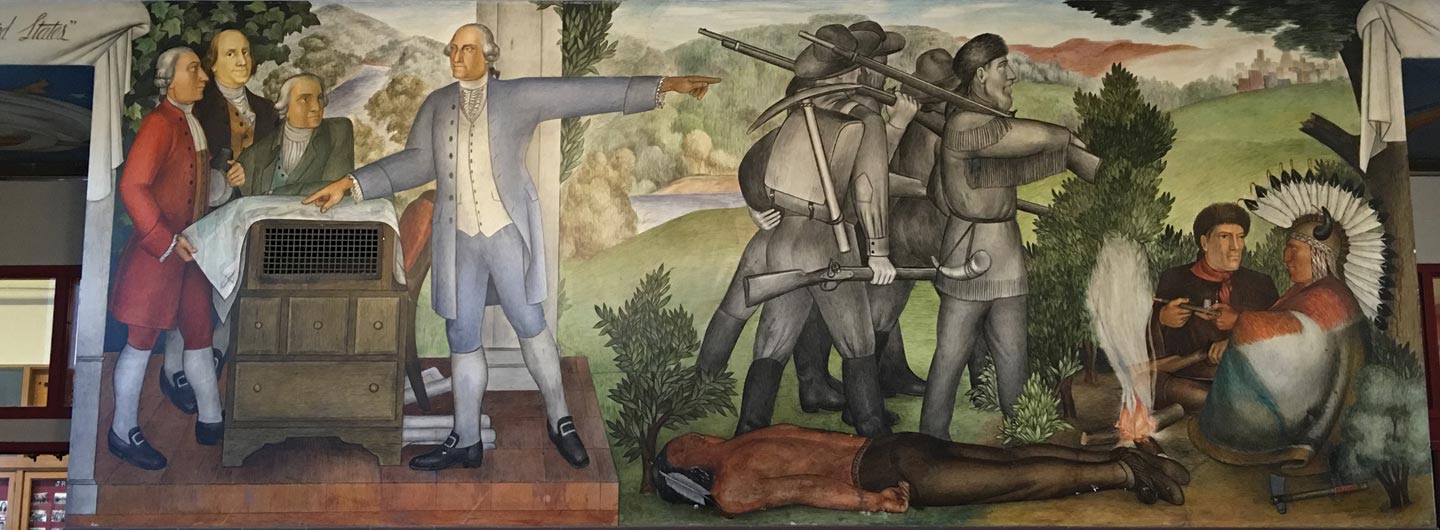

On June 25, the San Francisco School Board voted to destroy Victor Arnautoff’s Depression-era mural series Life of Washington at George Washington High School because it was deemed racist and demeaning. Some students and educators—as well as school board officials, indigenous groups, and various black and Latinx leaders—have singled out two of the murals, which show enslaved Africans and a disturbing image of a dead Indian. The work’s critics argue not only that it depicts history from the colonizers’ perspective but also that such violent images are triggering. The school board’s decision provoked a national campaign in defense of Arnautoff’s work, with proponents citing First Amendment issues, the importance of historical memory, the failure to grasp the radical intent behind the mural series, and the absurdity of spending $600,000 that could have gone to fund arts education to destroy a work of art.

After dozens of editorials, blog posts, petitions, and weeks of rancorous debate, the school board recently struck a compromise that would preserve and digitize the murals but also shroud them behind removable covers. This eminently reasonable solution, however, should not mark the end of what is potentially a fruitful debate over how we interpret the past, who has the authority to do so, and how liberal multiculturalism has shifted our response to historical violence and exploitation. Unfortunately, few on either side of this debate have taken stock of earlier contestations over the murals’ meaning, which bear little resemblance to the current controversy. Looking back at the long fight over Life of Washington exposes a gaping deficit in historical thinking—one that has infected contemporary political discourse and impoverished our capacity to think beyond spectacle.

Popular

"swipe left below to view more authors"Swipe →Culture wars make for strange bedfellows. Conservative New York Times columnist Bari Weiss joined with progressives like Aijaz Ahmad, Wendy Brown, Judith Butler, Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, and Adolph Reed in defending Arnautoff’s work. The right sees the attack on Life of Washington as the latest skirmish in the left’s war on America and its symbols and traditions. Victor Davis Hanson, a historian affiliated with the right-wing Hoover Institution at Stanford University, penned an op-ed for the Chicago Tribune that linked the murals’ impending erasure to several attacks on America by liberals, from comments by Representative Ilhan Omar and soccer star Megan Rapinoe to the toppling of Confederate statues. He warned, “If progressives and socialists can at last convince the American public that their country was always hopelessly flawed, they can gain power to remake it based on their own interests…. We’ve seen something like this fight before, in 1861—and it didn’t end well.”

The Civil War didn’t end well?! The abolition of formal chattel slavery? The 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution and the boldest attempt to extend democracy to all Americans before the 1960s? True, Reconstruction certainly did not end well, with the planter class and New South industrialists regaining power and installing the Jim Crow racial regime. But it took over three decades of white terrorism, political assassination, lynching, disfranchisement, and federal complicity to crush what W.E.B. Du Bois called “the abolition democracy.” For landlords and capitalists, that ended pretty well. They celebrated by erecting monuments to Confederate war heroes and promoting D.W. Griffith’s cinematic adoration of the Ku Klux Klan, Birth of a Nation. They employed art to invent myths, turning terrorists and slaveholders into saviors and obliterating traces of black struggles for social democracy.

Of course, Confederate monuments were not exactly art. More often than not, they were mass-produced statues installed for the purpose of erasing history and declaring the rule of white supremacy. But it is also a mistake to consider Arnautoff’s depiction of Washington as the true and authentic history that students can read as a counternarrative to the dominant story. Arnautoff did not paint these murals so that future generations would not forget the terrible parts of the past. While contemporary structural racism is rooted in the colonial era, the link between past and present is not self-evident in the murals—nor should it be. It is the responsibility of educators to make these connections, though judging from arguments leveled on both sides of the debate, we’re not doing a very good job. In a frequently quoted passage defending the work, one George Washington High School student wrote, “The fresco is a warning and reminder of the fallibility of our hallowed leaders.”

Preservationists love this quote. The problem is that it rests on the liberal claim that America created the perfect union, but for a few flaws reflecting the founders’ human fallibility. That 41 slaveholders signed the Declaration of Independence is an unfortunate fact but doesn’t sully that noble document. Recall a few years ago when Democrats criticized Republicans for holding public readings of the Constitution and skipping over the “arcane” parts sanctioning slavery as a property right and a basis for congressional representation and taxation. Critics insisted that these politically uncomfortable passages should not be buried but acknowledged as evidence of the greatness of the Constitution for rising above the fallibility of its authors.

But slavery and dispossession were not errors or anachronisms; they were the foundation upon which American liberty was built. Kanye West had a point (almost): Slavery was a choice. Not for the kidnapped Africans but for the nation’s white settler class, the rulers who in their quest for wealth accumulation faithfully read their Plato and Aristotle for models of a slave owners’ republic; treated their own mixed-race offspring as property to be exploited, sold, or mortgaged; and drove enslaved people to build their shining city on a hill on the land and bodies of indigenous people. Lest we forget, British prohibitions against colonists moving into Indian territory west of the Appalachian Mountains was one of the catalysts for independence.

Washington led a war and a nation with the goal of securing liberty and equality for white men not because they harbored some natural or irrational hatred for Africans and Indians but because it was the only way to maintain racial slavery and legally sanction dispossession in a settler society based on liberal principles. Colonial landholders had to manage kidnapped African labor, unruly indentured white labor, and relations with sovereign and often powerful indigenous communities. The planters’ inability to police their workers and the frontier meant that white servants and African slaves often escaped, sometimes together, finding refuge in swamps, hills, and among Native peoples. Staving off the threat of what historian Peter Linebaugh calls “commoning”—the practice of living and working communally based on common ownership and mutual responsibility rather than private property and individualism—required freeing white servants and turning them into property owners, slave patrollers, or proletarian citizens invested in the white republic and the dream of attaining wealth and power.

The Constitution reinforced this arrangement by protecting slavery and empowering slaveholders. The three-fifths compromise apportioning congressional representation in the slave states by counting the white population along with 60 percent of enslaved people strengthened Southern power over the federal government. It was not a plot to reduce black people to three-fifths of a person as a symbolic act of dehumanization; enslavement and disfranchisement had already done that. And yet this utterly confusing metaphor is being peddled in schools to this day.

Life of Washington may not address all of this history, but it certainly opens the door for a deeper interrogation—so long as we move beyond the idea that the work is little more than a well-intentioned effort to represent racial violence or the fallibilities of a founding father.

Washington wasn’t just any white man, nor was Arnautoff. Born in southern Ukraine in 1896, he longed to be an artist but began his adult life as a career soldier, becoming a cavalry officer in World War I, then an officer in the White Army during the Russian Civil War. After the Bolshevik victory, he fled to China, where he studied art briefly before joining the cavalry of a Manchurian warlord. In 1925 he enrolled in the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco and in 1929 studied mural painting in Mexico under the tutelage of Diego Rivera. Returning to San Francisco in 1931, Arnautoff soon became one of the city’s leading muralists. His 1934 mural City Life in Coit Tower attracted controversy for its left-wing imagery. As a student of Rivera’s and a supporter of the city’s 1934 general strike, Arnautoff was drawn to the orbit of the Popular Front. (He joined the Communist Party in 1938.) By 1935, when the city asked him to create a massive fresco for the newly constructed George Washington High School, he was already a well-known figure on the left.

Aware of his limited knowledge of US history, the émigré thoroughly researched Washington’s life and times as well as the early history of the republic. As he recalled in his memoir, “First I endeavored to study the life and work of this famous man, a committed defender of freedom. I got books and materials relating to him…. I wanted not only to show Washington’s life—that was half the idea—but also to show his beauty of soul, the greatness of his dedication…. I tried my best to convey the spirit of Washington’s time.” Arnautoff also wanted to bring to the surface the spirit and dignity of labor, free and unfree, and expose the tensions of liberty. In 1935 he told one interviewer, “The artist is a critic of society…. I wish to deal with people, to explain to them things and ideas they may not have seen or understood.”

For artists in the American Communist Party’s orbit, the Popular Front was a broad-based response to fascism and an injunction to rethink American culture, art, and the circle of “we.” Communists promoted racial and ethnic diversity, identifying black art and artists as both inherently progressive and profoundly American. Arnautoff witnessed interracial movements among workers and the unemployed in San Francisco and was also painfully aware of the state’s policy of repatriating Mexican workers to solve the problem of white unemployment. A regular reader of the Western Worker, he was doubtless familiar with the activities of Bay Area Native American communists such as Joe Manzanares and might even have come across a letter by Vincent Spotted Eagle published by the paper in 1934, explaining that before the European invasion Indians created a cooperative economy free of exploitation. “This is Communism, which is true Americanism. And this is why I joined the Communist Party,” Spotted Eagle wrote.

Two years later, Communist Party USA chairman Earl Browder declared “Communism is 20th century Americanism” as the new slogan of the People’s Front. However, his Americanism derived not from indigenous traditions but from a reinterpretation of republicanism. In a 1937 essay he hailed the great triumvirate of Thomas Paine, Thomas Jefferson, and Washington, calling Washington “the popular symbol of national independence” and the central figure in the consolidation of the nation and the Constitution that binds it. “The honorary title of ‘Father of his Country’ given him by history is solidly based on historic fact.”

Arnautoff fused all of this—the recasting of American culture as multiracial, a resolute opposition to fascism, the reclamation of the so-called founding fathers for the American left—and his fascination with military history to create Life of Washington. These influences become clearer once we extend our gaze from the contested murals to the entire work. The two largest murals flank a staircase. One captures Washington’s early life as a surveyor (the principal technicians of enclosure), a military leader, and the master of his Mount Vernon plantation. A panel on the French-Indian War centers on two armed Native Americans backed by French soldiers after a successful ambush. The scene shows the surrender of three colonial soldiers and another lying dead on the ground. On the opposite side are iconic images of the Boston Tea Party, the Stamp Act protests, and the Boston Massacre. The center of the panel consists of five revolutionaries from the plebeian ranks raising the flag declaring the new nation.

Arnautoff never spoke publicly about the nature of his mural series’ counternarratives. His biographer Robert W. Cherny argues that the compositional placement of enslaved Africans, indigenous people, and working-class revolutionaries highlights “the incongruity that Washington and others among the nation’s founders subscribed to the declaration that ‘all men are created equal’ and yet owned other human beings as chattel. Arnautoff’s mural makes clear that slave labor provided the plantation’s economic basis. On the facing wall, [he] was even more direct: The procession of spectral future pioneers move west over the body of a dead Indian, challenging the prevailing narrative that westward expansion had been into largely vacant territory waiting for white pioneers to develop its full potential.”

Although some of his current defenders on the left see the mural series as a Trojan horse smuggling in a withering critique of Washington as a slaveholder and architect of manifest destiny, Arnautoff saw it as a paean to a great patriot and “committed defender of freedom.” This was no cynical ploy to appease the Works Progress Administration and the city or stave off possible criticism or even evidence of his ideological ambivalence.

The unveiling of Life of Washington in 1936 was met with critical acclaim but with no mention of Arnautoff’s subtle indictments of slavery and dispossession. It’s also not clear what the predominantly white student body thought about the work in those early years. But as black migration and immigration from Latin America and Asia—and the radical insurgencies of the 1960s—transformed the Bay Area’s politics and demographics, the murals became a focus of contention. In the spring of 1968, during a schoolwide discussion of racial tensions at Washington High, a group of black students expressed resentment over the work’s representation of African Americans. They did not object to Arnautoff’s depiction of slavery itself but rather the “one-sidedness of the presentation.” Daryl Thomas, the president of the school’s Afro-American Club, called for the inclusion of artworks depicting “the contributions of black people to the sciences and industry” and proposed hanging “photographs of Negroes who have made important contributions.” At the time, no one complained about the dead Indian.

The students met with members of the school administration and San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto, all of whom agreed that something should be done to address their concerns. But when the fall term began and no action was taken, tensions over the murals flared again. Led by the Black Student Union (which replaced the Afro-American Club), more than 80 black students assembled to demand that the work be destroyed or altered. The BSU’s president, Roosevelt Thomas, complained, “The blacks did more than just pick cotton. During the Revolution, more than 5,000 blacks fought for this nation’s independence.” Arnautoff’s sons and a few other artists were on hand to defend the work, saying that his decision to include Washington’s slaves was a bold effort to expose an injustice rarely acknowledged in the 1930s. Principal Ruth Adams presented a poll finding that 61 percent of the student body preferred to supplement rather than destroy the murals.

The debate persuaded the BSU to withdraw its demand for the fresco’s destruction, conceding that it is “historically sound and should remain on view.” Instead, the group proposed placing plaques alongside the panels to “explain their ‘deficiencies’” and commissioning an additional mural as a corrective. Ironically, several of the suggestions would have further ennobled Washington and the War of Independence without ever confronting Arnautoff’s implicit critique of slavery and dispossession. For example, the BSU called for the inclusion of Crispus Attucks as the first (patriot) casualty of the Boston Massacre as well as the black men who served in Washington’s army (an idea floated more recently by Stevon Cook, the president of the San Francisco Board of Education and the murals’ fiercest critic). No one spoke up for the thousands of fugitive slaves who joined British loyalist forces and won their freedom—but became exiles. The students did not protest the murals’ depictions of violence and brutality; rather, they wanted inclusion in the citizenry of the white republic. And once again, no one complained about the dead Indian.

The overwhelming consensus in the BSU was to commission a black artist for a new mural. But before that plan could move forward, the struggle ratcheted up another notch. In February 1969, BSU members hung a poster on campus of Bobby Hutton, a member of the Black Panther Party, with the words “Murdered by Oakland pigs.” Several months earlier, the 17-year-old Hutton had been shot to death while surrendering to police with his hands in the air. When four white students complained that the poster was offensive, the administration promptly had it removed. The decision provoked outrage from black students who argued that the killing of Hutton represented their history, “as did the murals at Washington portraying black slavery.” They called out the administration for employing a racist double standard.

The black students, however, did not complain of psychological harm or traumatizing violent images. If anything, they preferred more violence in the mural—the violence of armed rebellion, slave revolts, and anti-colonial resistance. They objected to portraying the enslaved and colonized as victims, working faithfully, lying prostrate, dead. So they sought out a black artist of their generation, someone familiar with the politics of black power, brown power, yellow power, and red power. They chose Dewey Crumpler, an activist and a graduate of San Francisco’s Balboa High School studying at the San Francisco Art Institute. When the commission was finally approved in 1970, Crumpler was just 22, though he had an impressive résumé. Upon receiving the commission he went to Mexico to study with muralists—including Pablo O’Higgins and David Alfaro Siquieros, whom he met through Elizabeth Catlett, a brilliant African American artist living in exile in Cuernavaca. A veteran of the left, she too was influenced by Rivera.

Crumpler took time to study Arnautoff’s murals and came to appreciate their value as art and as a social statement. He informed the students that he was interested not in replacing Life of Washington but in creating a work in dialogue with Arnautoff’s work—and with them. Completed in 1974, Crumpler’s dynamic Multi-Ethnic Heritage celebrated the cultural, political, and intellectual histories of African American, Latinx, Asian American, and indigenous peoples. Incorporating portraits of Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., Simón Bolívar, Cesar Chavez, and Dolores Huerta (among others), the mural’s three panels are linked by a motif of chains breaking. The central figure in the panel dedicated to African American heritage is a black woman, issuing from a broken chain like a phoenix rising above a flame. For the Native American panel, Crumpler explained, he painted an Indian “holding up Turtle Island, which was Alcatraz. That Native American would be an archetype, with his body stretched out into the sky, not dead but fully alive. And articulated as the blood of the earth, with the red soil, the energy of the earth.”

Today Crumpler is among the most outspoken and authoritative defenders of Life of Washington. He has said on countless occasions, “My mural is part of the Arnautoff mural, part of its meaning, and its meaning is part of mine. If you destroy his work of art, you are destroying mine as well.” He devoted years to creating the work in conversation with a generation of Washington High students whose struggles for dignity, knowledge, and power convinced them of the value of art—even art we don’t immediately understand or that challenges our common sense.

I find it ironic that Mark Sanchez, the vice president of the school board, used the word “reparations” to describe the $600,000 cost of the Arnautoff murals’ erasure. In doing so, he not only perverts the concept of reparations but also fails to see that precious funds that could have been invested in arts education or an anti-racist curriculum will be used to cover up a work that actually makes a powerful case for reparations by revealing how white liberty and the wealth of the new nation were built on slavery, colonialism, dispossession, and genocide. Certainly, students can learn this in their classrooms, and they can see it in the streets of San Francisco as rising rents and corporate land grabs continue to displace poor black and brown people in the city. I hope that future generations will possess the courage and the curiosity to rediscover Arnautoff’s murals and the world in which they were created. For by revisiting the era of labor insurgency, anti-fascism, and anti-eviction campaigns, students might learn the most valuable lessons of all.