Dear Liza, Should I quit my job as a prosecutor for the Department of Homeland Security (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) and work for a nonprofit at half the salary? I hate myself for the work I do, but I’m a single mom with three kids. Right now I’m paying one son’s college tuition and am $40K in debt for my other son’s tuition. And I have a 13-year-old coming up. —Down (or Out) at DHS

Dear Down (or Out),

Don’t hate yourself! Instead, hate the system that forces many of us to do horrible things to support ourselves and our kids.

I do, however, think you can make choices that would be better for you, your children, and the world.

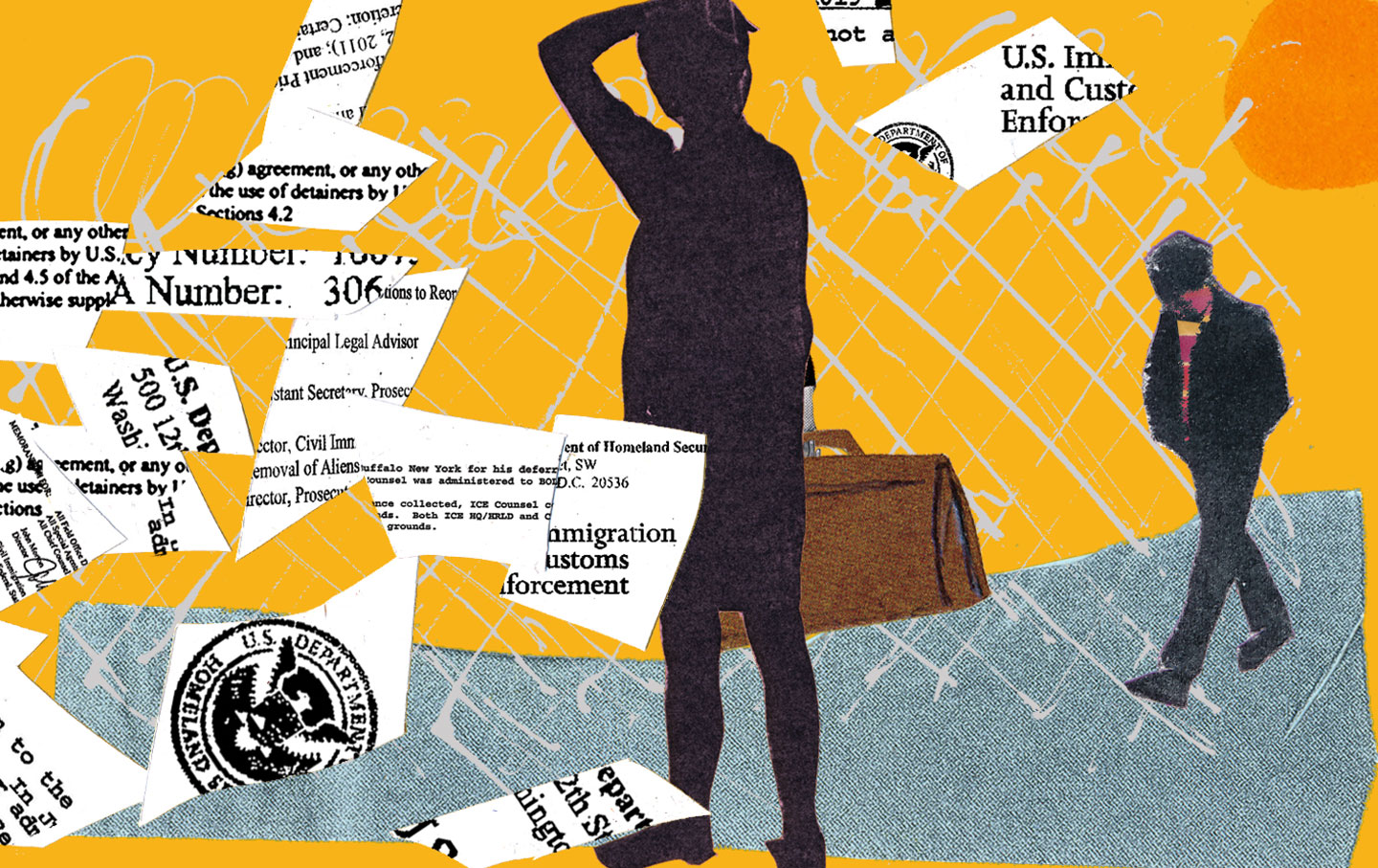

For readers unfamiliar with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, it’s an agency that apprehends immigrants who have usually committed no crime except crossing the border. ICE often sends them to detention centers, where they are treated like criminals and may be held indefinitely under awful conditions. ICE also sends people back to their home countries, often breaking up families. Some of these migrants are children fleeing violence. Michelle Chen wrote recently in The Nation about a teenager who was excelling in his high school in North Carolina, until ICE shipped him to a detention center in Georgia, where his teachers, at one point, were blocked from bringing him his homework. ICE is attempting to send the boy back to Honduras; if he returns, his family believes he will die at the hands of violent gangs—the reason he left that country in the first place.

If you were a prosecutor in a different branch of government, you would, at least now and then, pursue criminals who deserve punishment. But ICE does nothing other than enforce our broken immigration laws and ruin people’s lives.

Not only is your work at ICE harmful, Down (or Out); you don’t even make enough money as a government prosecutor to send all these kids to college. You’re hardly starving, but you make less than $150,000 a year (and possibly less than half that), while private college tuition averages $31,231 a year (and the cost of public college is also climbing rapidly).

So the answer to your question: Yes, you should quit. Your work at a nonprofit will probably be more rewarding for you and better for society. With your lower salary, your youngest (and possibly also your middle child) will be eligible for more financial aid.

Children benefit from seeing their parents satisfied in their work. We risk burdening our kids with guilt—and providing them with an uninspiring model of adulthood—when we make sacrifices for them that we cannot morally justify to ourselves. Your situation is difficult, for sure, but you have more choices than many people do, and you’ve already given up plenty for these kids. Now it’s time to set them a good example by leading a happier and more engaged life.

Dear Liza, Listen, whenever I can, I buy books in small independent bookstores. Only if a book is difficult to find do I order it on Amazon. But for my life’s other needs? Amazon is just so much more convenient than trawling all the local stores I would need to hit to find said item, and it’s cheaper too. How many times have you walked into a mom-and-pop hardware store that didn’t have the goods you were looking for? I, for one, need some 15-amp screw-in fuses, because I live in a dilapidated Brooklyn home that still uses them. Do hardware stores even carry those any more? So I order them on Amazon. Am I a monster? —Amazon Addict

Dear Addict,

As an author, I thank you for supporting independent bookstores and avoiding buying books from Amazon, a company that has made it tough for anyone in the book industry other than itself to make money.

As people of letters, we tend to feel the badness of Amazon is all about us, but there are many workers who are even more screwed by this company. Amazon deploys a creepy fusion of technology and Taylorism to keep workers under a relentless system of surveillance. Journalist Simon Head, in his book Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans, calls it “the most oppressive I have ever come across.” Head writes about an Amazon warehouse employee in Allentown, Pennsylvania, who worked 11-hour shifts and was fired for being unproductive on the job for several minutes. Ambulances were stationed at the same warehouse on hot summer days to take employees suffering from heat stroke to the hospital; the 110-degree warehouse had no air-conditioning, and Amazon management refused to open the loading doors for fear of theft. Not surprisingly, several workers at Amazon’s fulfillment centers have died on the job.

Still, scouring Brooklyn’s few small hardware stores for 15-amp fuses isn’t a good use of your time; you’d probably just end up going to Home Depot anyway. In any case, this type of exercise in individual consumer virtue doesn’t change anything. Consumer boycotts of such large companies are mostly useless unless they’re massive in scale. Also, Amazon has been notoriously successful in fighting off unions, using secret meetings and high-priced union-busting law firms.

Amazon workers need labor-law reform, which would enable them to organize unions more easily, and better enforcement of health and safety laws. To achieve those things, we need to organize our own workplaces (or help others to do so), elect more progressive people to national office, and build a labor movement independent of the Democratic Party.

We can also support organizations pressing for better conditions for Amazon workers, including the Warehouse Worker Resource Center, a nonprofit that accepts donations, and the Teamsters, who are running a Justice for Port Drivers organizing campaign. So consider your Amazon Prime membership a gift of time and money—both of which you can spend creating a far more hostile environment for Amazon.

Have a question? Ask Liza here.

Liza FeatherstoneTwitterLiza Featherstone is a Nation contributing writer and the author of Divining Desire: Focus Groups and the Culture of Consultation.