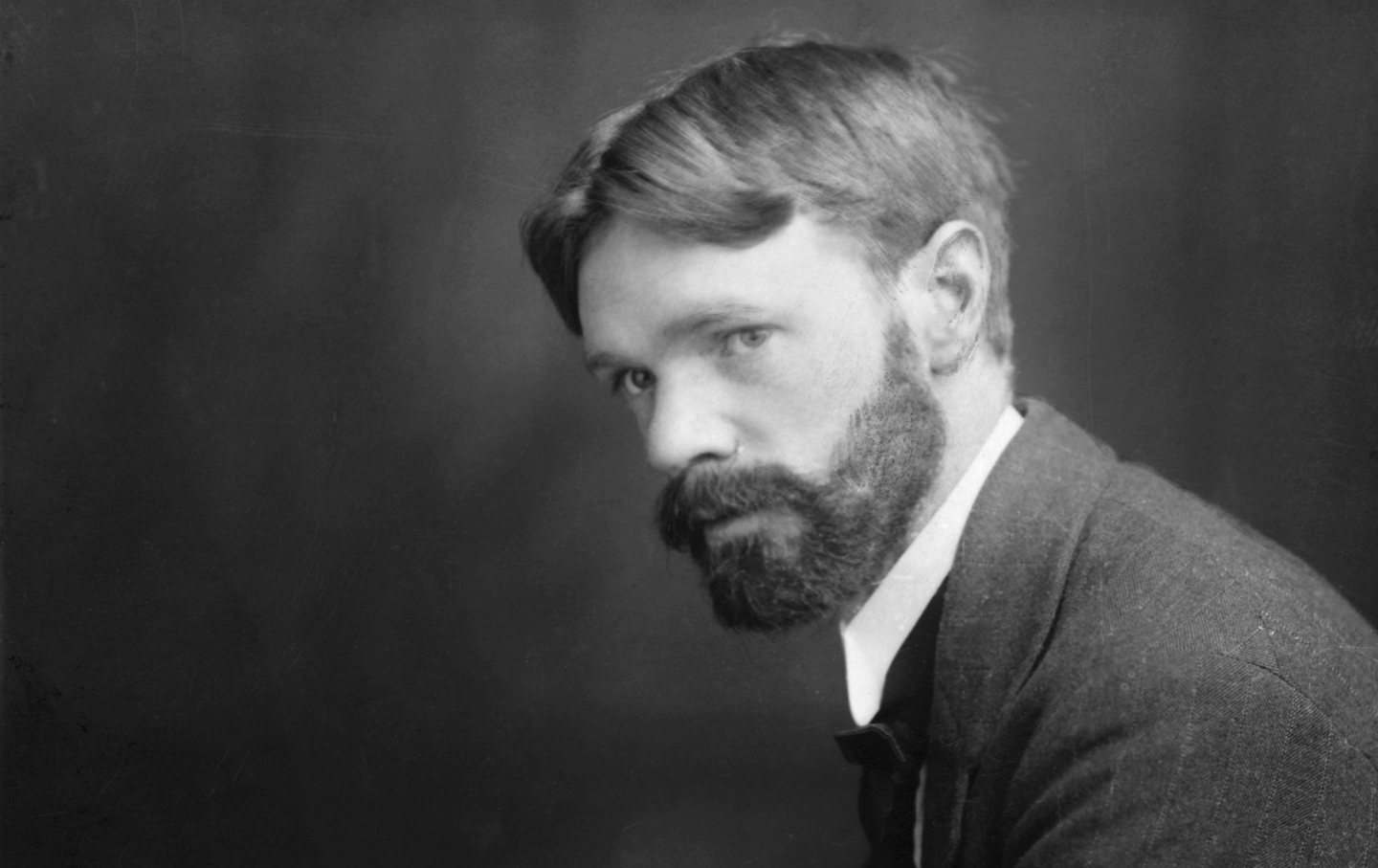

The English novelist D.H. Lawrence (1885–1930).(Photo by © Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis / Corbis via Getty Images)

D.H.Lawrence, by his own measure, was large. “I am not one man,” he wrote. “I am many, I am most.” A hearty Whitmanic appetite like this makes sense when you consider the scope of his life’s work—12 novels, four travel books, numerous plays and critical studies, and multiple collections of short stories and poetry, not to mention thousands of letters—but if you hack through the catalog, looking for a singular Lawrence somewhere in the “many,” you come up against an uncomfortable clump of traits. The Bad Side of Books, a new collection of Lawrence’s essays edited by Geoff Dyer, reveals the English writer to be a man who, among other things, loathes democracy, admires strongmen and decisive rulers, tends toward half-truths and half-baked ideas, celebrates impulse and instinct over intellection, prefers myth over history, exoticizes “Indians” and all “dark races” in the moments he’s not disgusted by them, and suggests that women—even when he blames bad men for their behavior—are ultimately subservient and half-witted. He’s also not thrilled about Jewish or English people.

But for every four times Lawrence disparages women or democracy, there will be another he does the opposite. It has allowed his readers to put varying emphasis on the offenses and contradictions over the decades. In the 1930s, after his death at 44, some admirers saw a poor, tubercular man needing defense. There were obituaries and tributes, attempts to salvage his legacy and shift the focus away from his censorship, exile, and reputed sex mania. In the 1950s, after years of dormancy, there was a revival. The critic F.R. Leavis campaigned for Lawrence feverishly, and a spate of biographies and studies were issued alongside new editions of his novels. After Lady Chatterley’s Lover triumphed in a landmark obscenity trial in 1960, the counterculture rediscovered Lawrence as the lone working-class modernist of English literature, the coal miner’s son who had run off with a German aristocrat, the red-bearded devotee of lovemaking, and the hot-blooded critic of heartless industry and bourgeois smugness. In the 1970s, there was Kate Millet’s Sexual Politics, which revealed Lawrence to be a woman hater and “pontiff,” in another critic’s words, “of a murderous phallic cult.”

His reputation has always been in flux, variably recuperated and dispatched. And as a critic, you walk into this trap. The ballot boxes are groaning with a century’s worth of slips, and yet here we are again: For or against?

Generally, the judgment rests on the novels. Most people rush for Sons and Lovers, The Rainbow, Women in Love, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and maybe they’ll savor a book of poems or two, but the nonfiction, besides Studies in Classic American literature, is largely neglected. Many scholars, on the other hand, tend to use the essays as critical tools for chipping away at the fiction. As with other modernists, Lawrence’s essays are often overlooked as literature, even though many of them are just as formally compelling as his stories and novels.

Lawrence told Catherine Carswell, a close friend and correspondent, that a 1922 essay of his introducing the memoirs of Maurice Magnus, a travel writer and a member of the French Foreign Legion, was “the best single piece of writing, as writing, that he had ever done.” It’s included in this collection, and I think he’s right. Let him travel, unleash him on a debauched person like Magnus, give him sense perceptions and concrete details to chew on—what happens is stunning or at least can be. The essay has the taut plot of a short story, with flawed and lively characters, and gathers lyrical descriptions, of cold monasteries and decrepit hotels and Mediterranean landscapes, and also sharp polemic, fulminations against war and technology. It’s a piece of prose that is supple and vast and free of genre.

Dyer has selected an exemplary range of essays on travel, nature, people, painting, and literature, but none of them are really about these things. They often veer into arguments or declarations about primeval man, blood, and throbs in the cosmos. In every essay, Lawrence fills his sentences with the connective tissue of logical reasoning—so’s and of course’s and thus’s and therefore’s—but there’s typically a deficit of logic or reasoning. His study of Thomas Hardy, for instance, begins with a close reading of the novels but then swerves into pages of reflection on the universal “Will-to-Motion we call the male will or spirit, [and] the Will-to-Inertia the female.” An account of Paul Cézanne tries to penetrate his “artistic soul”—informing us that Cézanne wanted “to be himself in his procreative blood” (your guess is as good as mine)—but doesn’t say much about who the Frenchman was or what he painted. It’s mostly associative claims that amount to homemade pseudophilosophy and baseless psychologizing.

Lawrence certainly has a keen eye for detail and a sensitive barometer for metaphysical vibrations, but it’s still hard sometimes to stomach his bullshit. In “A Letter From Abroad (The Death of D.H. Lawrence)” from 1930, Rebecca West described the first time she met Lawrence, on a day he arrived in Florence by train from Rome. West, along with Norman Douglas, a writer and friend of Lawrence’s, went to greet him at his hotel on the Arno. They entered Lawrence’s squalid, viewless room, and there he was clacking away on a typewriter. Douglas burst into laughter and asked Lawrence if he was writing an article about “the present state of Florence,” and Lawrence replied that he was. “This was faintly embarrassing,” West wrote, “because on the doorstop Douglas had described how on arrival in a town Lawrence used to go straight from the railway station to his hotel and immediately sit down and hammer out articles about the place, vehemently and exhaustively describing the temperament of the people.”

There were times while reading this collection that I was tempted to forgive him. His sentences are so unbridled and fresh, and so weirdly perfect. Even when he chars a subject, reduces it to ash, the prose is still large and additional like a flame, wondrously rippling in the air. He can be on a fascistic rant about the rightful domination of lower life-forms and describing something as ordinary as a cow, and we still receive this gift:

So Susan, swinging across the field, snatches off the tops of the little wild sunflowers as if she were mowing. And down they go, down her black throat. And when she stands in her cowy oblivion chewing her cud, with her lower jaw swinging peacefully, and I am milking her, suddenly the camomiley smell of her breath, as she glances round with glaring, smoke-blue eyes, makes me realize it is the sunflowers that are her ball of cud. Sunflowers! And they will go to making her glistening black hide, and the thick cream on her milk.

There is much of Lawrence here—the alliteration, the repetition, his obsession with dark things and blue things, his loving notice of flowers, the diminutive y’s, the string of clauses linked lightly with commas, and of course, the exclamation mark, which pricks and caffeinates so many of his sentences.

My favorite version of Lawrence in the collection is the middle-aged man, the one who digs back, with uncertainty, toward his childhood in “On Coming Home” (1924–25), “Return to Bestwood” (1926), and “Nottingham and the Mining Countryside” (1929). When he wrote these pieces, he had spent most of his adult life on the move (living in Italy, Australia, America, and France before his death), but when he looks at the England he grew up in, he sees both the old and the new, agriculture and industry, and it leaves him with “devouring nostalgia and an infinite repulsion.” Industry seems ugly at first, but then it’s suddenly beautiful—the pitheads wedged into the earth, the burning pit banks, the luster of coal, the sulfur smell, the turning gin wheels, the rattle of trains, the flakes of soot on the flowers. He remembers colliers surfacing from the mines, blinking in the light, streaming homeward: “the ringing of the feet, the red mouths, and the quick whites of the eyes.”

In Lawrence’s mind, these men are perfect. He believes that they lived instinctively and intuitively, with no intrusion of abstract thought, and that they had an appreciation for true unrefined beauty, and that somehow, despite the punishing toil and life-threatening labor, they did not care about wages. It’s astonishing. Even when he’s writing about the places he knows best, his vision is still vividly fogged and clotted with fantasy.

Awe and loathing, awe and loathing—this is the rhythm of reading Lawrence today. It is a long switchback road, and I never know where to get off. Some critics vanish the difference between form and content, but with Lawrence, there seems to be a fissure. Beauty separated from bile: beautiful form that obscures its content and bilious content that obscures its form. But maybe I’m imagining it. Maybe it’s all bile. His politics, after all, are scattered and terrible. If there is beauty in his writing, it’s what his lyricism makes possible for other writers and readers.

Zachary Fineis a writer from New Orleans.